Saraswati veena

|

Saraswati veena | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Saraswati guitar |

| Classification | string |

| Musicians | |

| Veenai Dhanammal, Sundaram Balachander, Chitti Babu, Kalpakam Swaminathan, E. Gayathri, Rajhesh Vaidhya, Jayanthi Kumaresh | |

| More articles | |

| Rudra veena, Vichitra veena, Chitra veena | |

The Sarasvati vīṇa (also spelled Saraswati vina) ( Tamil: வீணை, Bengali: সরস্বতী বীণা , Sanskrit: वीणा (vīṇā), Kannada: ವೀಣೆ, Malayalam: വീണ, Telugu: వీణ) is an Indian plucked string instrument. It is named after the Hindu goddess Saraswati, who is usually depicted holding or playing the instrument. Also known as raghunatha veena is used mostly in Carnatic Indian classical music. There are several variations of the veena, which in its South Indian form is a member of the lute family. One who plays the veena is referred to as a vainika.

It is one of other major types of veena popular today. The others include chitra veena, vichitra veena and rudra veena. Out of these the rudra and vichitra veenas are used in Hindustani music, while the Saraswati veena and the chitra veena are used in the Carnatic music of South India. Some people play traditional music, others play contemporary music.

History

The veena has a recorded history that dates back to the approximately 1500 BCE.

In ancient times, the tone vibrating from the hunter's bow string when he shot an arrow was known as the Vil Yazh. The Jya ghosha (musical sound of the bow string) is referred to in the ancient Atharvaveda. Eventually, the archer's bow paved the way for the musical bow. Twisted bark, strands of grass and grass root, vegetable fibre and animal gut were used to create the first strings. Over the veena's evolution and modifications, more particular names were used to help distinguish the instruments that followed. The word veena in India was a term originally used to generally denote "stringed instrument", and included many variations that would be either plucked, bowed or struck for sound.[1][2]

The veena instruments developed much like a tree, branching out into instruments as diverse as the harp-like Akasa (a veena that was tied up in the tops of trees for the strings to vibrate from the currents of wind) and the Audumbari veena (played as an accompaniment by the wives of Vedic priests as they chanted during ceremonial Yajnas). Veenas ranged from one string to one hundred, and were composed of many different materials like eagle bone, bamboo, wood and coconut shells. The yazh was an ancient harp-like instrument that was also considered a veena. But with the developments of the fretted veena instruments, the yazh quickly faded away, as the fretted veena allowed for easy performance of ragas and the myriad subtle nuances and pitch oscillations in the gamakas prevalent in the Indian musical system.[2] As is seen in many Hindu temple sculptures and paintings, the early veenas were played vertically. It was not until the great Indian Carnatic music composer and Saraswati veena player Muthuswami Dikshitar that it began to be popularized as played horizontally.

"The current form of the Saraswati veena with 24 fixed frets evolved in Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, during the reign of Raghunatha Nayak and it is for this reason sometimes called the Tanjore veena, or the Raghunatha veena. Prior to his time, the number of frets on the veena were less and also movable." - Padmabhooshan Prof. P. Sambamurthy, musicologist.[3] The Saraswati veena developed from Kinnari Veena. Made in several regions in South India, those made by makers from Thanjavur in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu are to date considered the most sophisticated. However, the purest natural sound is extracted by plucking with natural fingernails on a rosewood instrument construction, which is exemplified by the grandeur of the Mysore Veena. Pitapuram in East Godavari District and Bobbili in vijayanagaram District of Andhra Pradesh are also famous for Veena makers. Sangeeta Ratnakara calls it Ekatantri Veena and gives the method for its construction.

While the Saraswati veena is considered in the lute genealogy, other North Indian veenas such as the Rudra veena and Vichitra veena are technically zithers. Descendants of Tansen reserved Rudra Veena for family and out of reverence began calling it the Saraswati Veena.

Construction

_of_Saraswati_Veena.jpg)

About four feet in length, its design consists of a large resonator (kudam) carved and hollowed out of a log (usually of jackfruit wood), a tapering hollow neck (dandi) topped with 24 brass or bell-metal frets set in scalloped black wax on wooden tracks, and a tuning box culminating in a downward curve and an ornamental dragon's head (yali).If the veena is built from a single piece of wood it is called (Ekantha) veena. A small table-like wooden bridge (kudurai)—about 2 x 2½ x 2 inches—is topped by a convex brass plate glued in place with resin. Two rosettes, formerly of ivory, now of plastic or horn, are on the top board (palakai) of the resonator. Four main playing strings tuned to the tonic and the fifth in two octaves (for example, B flat-E flat below bass clef - B flat- E flat in bass clef) stretch from fine tuning connectors attached to the end of the resonator across the bridge and above the fretboard to four large-headed pegs in the tuning box. Three subsidiary drone strings tuned to the tonic, fifth, and upper tonic (E flat - B flat- E flat in the tuning given above) cross a curving side bridge leaning against the main bridge, and stretch on the player's side of the neck to three pegs matching those of the main playing strings. All seven strings today are of steel, with the lower strings either solid thick.

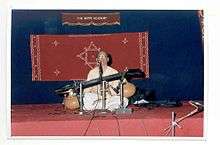

Playing technique

.jpg)

The veena is played by sitting cross-legged with the instrument held tilted slightly away from the player. The small gourd on the left rests on the player's left thigh, the left arm passing beneath the neck with the hand curving up and around so that the fingers rest upon the frets. The palm of the right hand rests on the edge of the top plank so that the fingers (usually index and middle) can pluck the strings. The drone strings are played with the little finger. The veena's large resonator is placed on the floor, beyond the right thigh. The photo of Veenai Dhanammal more accurately illustrates how the veena is held than the more fanciful Ravi Varma painting.

Like the sitar, the left hand technique involves playing on the frets, controlled pushing on the strings to achieve higher tones and glissandi through increased tension, and finger flicks, all reflecting the characteristics of various ragas and their ornamentation (gamaka). Modern innovations include one or two circular sound holes (like that of the lute), substitution of machine heads for wooden pegs for easier tuning, and the widespread use of transducers for amplification in performance.

Religious associations within Hinduism

The patron Hindu Goddess of learning and the arts, Saraswati, is often depicted seated upon a swan playing a veena. Lord Shiva is also depicted playing or holding a vina in His form called "Vinadhara," which means "bearer of the vina." Also, the great Hindu sage Narada was known as a veena maestro.[4] and refers to 19 different kinds of Veena in Sangita Makarandha. Ravana, the antagonist of the Ramayana, who is also a great scholar, a capable ruler and a devoted follower of Shiva, was also a versatile veena player. Scholars hold that as Saraswati was goddess of learning, the most evolved string instrument in a given age was placed in her hands by contemporary artistes.

References in ancient texts and literature

The Ramayana, the Bhagavata and Puranas all contain references to the Veena, as well as the Sutra and the Aranyaka. The Vedic sage Yajnavalkya speaks of the greatness of the Veena in the following verse: "One who is skilled in Veena play, one who is an expert in the varieties of srutis (quarter tones) and one who is proficient in tala attain salvation without effort."[5]

Many references to the veena are made in old Sanskrit and Tamil literature, and musical compositions. Examples include poet Kalidasa's epic Sanskrit poem Kumarasambhava, as well as "veena venu mridanga vAdhya rasikAm" in Meenakshi Pancharathnam, "mAsil veeNaiyum mAlai madhiyamum" Thevaram by Appar.[6]

Each physical portion of the veena is said to be the seat in which subtle aspects of various gods and goddesses reside in Hinduism. The instrument's neck is Shiva, the strings constitute his consort, Parvati. The bridge is Lakshmi, the secondary gourd is Brahma, the dragon head Vishnu. And upon the resonating body is Saraswati. "Thus, the veena is the abode of divinity and the source of all happiness."- R. Rangaramanuja Ayyangar[7]

Variants

Scholars consider that today four instruments are signified by Veena which in the past has been used as generic name for all string instruments. They are the Tanjavur (Saraswati) Veena, Rudra veena, Vichitra veena, and Gottuvadhyam veena (also called the Chitra veena).

Modern day evolving of the veena include the Sruti veena (more an instrument for theoretical demonstration than for actual playing) that was constructed by Dr. Lalmani Misra in early 1960s on which all 22 srutis can be produced simultaneously,.[8]

Contemporary situation

Veena represents the system of Indian music. Several instruments evolved in response to cultural changes in the country. Communities of artists, scholars and craftsmen moved around and at times settled down. Thus Veena craftsmen of Kolkata were famous for their instruments. Similarly, Rudra Veena was given a new form which came to be known after the craftsmen of Tanjavur as Tanjavur Veena. Modern life-style is no longer limited to definite routine within a small locality, thus along with performers and teachers of Veena, the community of craftsmen is also on decline.[9] Attempts to start institutions of instrument-making have been made, but there is a strong need for conservatories which focus on all aspects of Veena. As a state party to UNESCO Convention 2003, India has identified Veena as an element of Intangible Cultural Heritage and proposed its inscription in the Representative list of UNESCO.

Electronic and Digital veena: Over the years, the acoustic Tanjavur veena (also known as Saraswati veena)has been used in solo and duet concerts in large auditoria. Performers have also been travelling across the globe for concerts. Many practitioners of the art live outside India. The challenges faced by them in using the acoustic veena: 1. Low sound output (volume) compared to other louder instruments like flute or violin, causing the sound of the veena to be almost inaudible in concerts comprising other instruments along with the veena. This necessitated use of a contact mike (pioneered by Emani Sankara Sastri) or magnetic pickup (pioneered by S.Balachander). Usage of these requires carrying an additional amplispeaker to enable audibility to the performer. 2. Fragility of the acoustic instrument, causing frequent breakage and damage during travel. 3. Requirement of re-fretting every year or so, necessitating either carrying the instrument back to India or facilitating the travel and stay overseas, of the skilled artisan from India for this specific purpose.

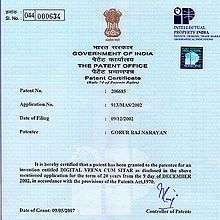

All these factors led to the creation of the rudimentary electric veena,followed by the electronic veena(1986) and digital veena (2002) by the engineer-flautist G Raj Narayan of Bengaluru.(1971)

The main characteristics of the electronic veena:

Enhanced volume, with the amplifier and speaker built into one of the gourds;

Built-in electronic tambura for sruti in the other removable gourd;

Matched pick-up and amplispeaker to enable authentic sweet veena sound;

Adjustable independent volume control for main and taala strings;

Adjustable frets on a wooden fret board, eliminating the more delicate wax fret board, frets can be adjusted easily by the user;

Guitar-type keys for easy and accurate tuning;

Complete portability, as the sound box of the veena is dispensed with, and replaced by a plank of wood. Easy assembly / disassembly;

Usage on battery in case of AC Mains power failure.

The electronic veena has gained popularity among users of the instrument. Videos of electronic veena concerts:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Qp6dhg3anY;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TgKKxyddXUk;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w8i4PW1z7SE; http://musicnagari.com/ladies-tanpura

However, this did not solve other issues such as need for repeated retuning while playing, change of strings for playing on higher pitch, mismatch of same note on different strings, etc. This led to the invention of the Digital veena (awarded a patent by the Indian Patent office),demonstrated at the Madras Music Academy in 2002. This is the first synthesiser for Indian music, and its salient features are:

Can be used at any pitch without changing strings;

All four strings and tala strings tuned automatically and perfectly on selection of ANY pitch;

Selection of PA / MA for mandara panchamam and taala panchamam strings – PA will change to MA on open string but first fret will still be Suddha Dhaivatam;

String will not change sruti while playing (frequency / sruti will not reduce or increase);

Gamakam response adjustment – can be set for high response to smaller transverse deflection of finger or small response to more deflection. e.g., Selection can be made so that with a moderate pull of string, five-note gamakam can be achieved on the same fret;

Enhanced volume, with the amplifier and speaker built-in to one of the gourds, adjustable volume;

Increased sustenance of notes; thus long passages can be played with fewer plucks, adjustable ‘sustain’ to suit a user’s style;

8 ‘voice’ choices ( types of sound) – e.g. Tanjore veena, mandolin, saxophone, flute, etc.;

Fixed frets on a wooden fret board, eliminating the more delicate wax fret board. No setting of melam. Digitally preset fret positions for perfect frequency of each note;

Built-in electronic tambura for sruti and line-out facility, battery back-up in case of AC Mains power failure;

Complete portability, as the sound box of the veena is dispensed with, and replaced by a detachable gourd with an ampli-speaker with easy assembly / disassembly.

The digital veena has also been used in concerts:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL78310529B34D2B20;

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL1DC8992449F99704;

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLPntK9cnRa695tzMidqD7r6CODCjrX3Gj

Tone and acoustics

Nobel Prize-winning physicist C.V. Raman has described the veena as having a unique construction. The string terminations at both ends are curved and not sharp. Also, the frets have much more curvature than any other instrument. Unlike in guitar, the string does not have to be pushed down to the very base of the neck, so no rattling sound is generated. This design enables a continuous control over the string tension, which is important for glissandi.

The beeswax beneath the frets may act as a noise filter.

Notable vainikas

Pioneers and legends

- Muthuswami Dikshitar

- Veenai Dhanammal (known for her individual style)

- Veena Sheshanna (Mysore style)

- Veena Subbanna (Mysore style)

- Veena Venkatagiriappa

- Veena Doraiswamy Iyengar (Mysore style)

- Emani Sankara Sastry (Andhra style)

- Chitti Babu (Andhra style)

- Karaikudi Sambasiva Iyer (Karaikudi style)

- Karaikudi Subbarama Iyer (Karaikudi style)

- K. S. Narayanaswamy (Travancore style)

- Trivandrum R Venkataraman (Travancore style)

- S Balachander (known for his individual style)

Other exponents

|

Veenai Dhanammal was one of the early exponents and legendary Veena player of Tamil Nadu

|

Contemporary artists

Rugmini Gopalakrishnan  Jayanthi Kumaresh performing a concert  Prince Rama Varma

Upcoming artists

|

- Y.G.Srilatha, Bangalore based Veena artist, disciple of Dr.Suma Sudhindra, Rank holder in Vidwat of Karnatka Board, All India Radio and Madras Academy Prize Winner, Youth Talent Promotion Awardee from Narada Gaana Sabha, Chennai,

Veena festivals

- Maargashira Veena Festival - since 2004 organized by Sri Guruguha Vaageyya Pratishtana Trust & Sri Guruguha Sangeeta Mahavidyala.[10]

- Mudhra Veenotsav - since 2005 at Chennai[11]

- Veena Navarathri - since 2007 at Chennai organized by the Veena foundation and the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts[12]

- International Veena conference and festival - since 2009 by Sri Annamacharya Project of North America (SAPNA)[13]

See also

References

- ↑ Bonnie C. Wade (2004). "Music in India". Manohar, 90-93.

- 1 2 Padma Bhushan Prof. P. Sambamurthy (2005). "History of Indian Music". The Indian Music Publishing House, 208-214.

- ↑ Padma Bhushan Prof. P. Sambamurthy (2005). "History of Indian Music". The Indian Music Publishing House, 203.

- ↑ Bhag-P 1.5.1 Narada is addressed as 'Vina-panih', meaning "one who carries a vina in his hand"

- ↑ Padma Bhushan Prof. P. Sambamurthy (2005). "History of Indian Music". The Indian Music Publishing House, 202, 205, 207.

- ↑ "See above".

- ↑ Bonnie C. Wade (2004). "Music in India". Manohar, 93.

- ↑ Shruti Veena: the Sound Link

- ↑ Forbes India: The last notes of Thanjavur Veena

- ↑ "10-day veena festival from Sunday". Shimoga. The Hindu. 7 December 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "Mudhra Veenotsav". Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "‘Veena Navarathri’ inaugurated". Chennai. The Hindu. 12 September 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Strings in dialogue". Hyderabad. The Hindu. 27 February 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saraswati veena. |

- Google - Saraswati Veena

- Saraswati Veena

- Rugmini gopalakrishnan

- Saraswati Veena in North Indian Khayal Style See Video of Beenkar Suvir Misra playing Saraswati Veena in Hindustani Khayal Style.