Sarah Orne Jewett

| Sarah Orne Jewett | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Theodora Sarah Orne Jewett September 3, 1849 South Berwick, Maine, U.S. |

| Died |

June 24, 1909 (aged 59) South Berwick, Maine, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist and short story writer |

| Literary movement | American literary regionalism |

| Notable works | The Country of the Pointed Firs |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Sarah Orne Jewett (September 3, 1849 – June 24, 1909) was an American novelist, short story writer and poet, best known for her local color works set along or near the southern seacoast of Maine. Jewett is recognized as an important practitioner of American literary regionalism.[1]

Early life

Jewett's family had been residents of New England for many generations, and Sarah Orne Jewett was born in South Berwick, Maine.[2] Her father was a doctor specializing in "obstetrics and diseases of women and children."[3] and Jewett often accompanied him on his rounds, becoming acquainted with the sights and sounds of her native land and its people.[4] As treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, a condition that developed in early childhood, Jewett was sent on frequent walks and through them also developed a love of nature.[5] In later life, Jewett often visited Boston, where she was acquainted with many of the most influential literary figures of her day; but she always returned to South Berwick, small seaports near which were the inspiration for the towns of "Deephaven" and "Dunnet Landing" in her stories.[6]

Jewett was educated at Miss Olive Rayne's school and then at Berwick Academy, graduating in 1866.[7] She supplemented her education through an extensive family library. Jewett was "never overtly religious," but after she joined the Episcopal church in 1871, she explored less conventional religious ideas. For example, her friendship with Harvard law professor Theophilus Parsons stimulated an interest in the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, an eighteenth-century Swedish scientist and theologian, who believed that the Divine "was present in innumerable, joined forms — a concept underlying Jewett's belief in individual responsibility."[8]

Career

She published her first important story in the Atlantic Monthly at age 19, and her reputation grew throughout the 1870s and 1880s. Her literary importance arises from her careful, if subdued, vignettes of country life that reflect a contemporary interest in local color rather than plot. Jewett possessed a keen descriptive gift that William Dean Howells called "an uncommon feeling for talk — I hear your people." Jewett made her reputation with the novella The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896).[9] A Country Doctor (1884), a novel reflecting her father and her early ambitions for a medical career, and A White Heron (1886), a collection of short stories are among her finest work.[10] Some of Jewett's poetry was collected in Verses (1916), and she also wrote three children's books. Willa Cather described Jewett as a significant influence on her development as a writer,[11] and "feminist critics have since championed her writing for its rich account of women's lives and voices."[8]

Later life

On September 3, 1902, Jewett was injured in a carriage accident that all but ended her writing career. She was paralyzed by a stroke in March 1909, and she died on June 24 after suffering another. The Georgian home of the Jewett family, built in 1774 overlooking Central Square at South Berwick, is now a National Historic Landmark and Historic New England museum called the Sarah Orne Jewett House.[12]

Jewett never married, but she established a close friendship with writer Annie Adams Fields (1834–1915) and her husband, publisher James Thomas Fields, editor of the Atlantic Monthly. After the sudden death of James Fields in 1881, Jewett and Annie Fields lived together for the rest of Jewett's life in what was then termed a "Boston marriage". Some modern scholars have speculated that the two were lovers.[13] Both women "found friendship, humor, and literary encouragement" in one another's company, traveling to Europe together and hosting "American and European literati."[8] In France Jewett met Thérèse Blanc-Bentzon with whom she had long corresponded and who translated some of her stories for publication in France.[14]

Selected works

- Deephaven, James R. Osgood, 1877

- Play Days, Houghton, Osgood, 1878

- Old Friends and New, Houghton, Osgood, 1879

- Country By-Ways, Houghton-Mifflin, 1881

- A Country Doctor, Houghton-Mifflin, 1884

- The Mate of the Daylight, and Friends Ashore, Houghton-Mifflin, 1884

- A Marsh Island, Houghton-Mifflin, 1884

- A White Heron and Other Stories, Houghton-Mifflin, 1886

- The Story of the Normans, Told Chiefly in Relation to Their Conquest of England, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1887

- The King of Folly Island and Other People, Houghton-Mifflin, 1888

- Tales of New England, Houghton-Mifflin, 1890

- Betty Leicester: A Story for Girls, Houghton-Mifflin, 1890

- Strangers and Wayfarers, Houghton-Mifflin, 1890

- A Native of Winby and Other Tales, Houghton-Mifflin, 1893

- Betty Leicester's English Christmas: A New Chapter of an Old Story, privately printed for the Bryn Mawr School, 1894

- The Life of Nancy, Houghton-Mifflin, 1895

- The Country of the Pointed Firs, Houghton-Mifflin, 1896

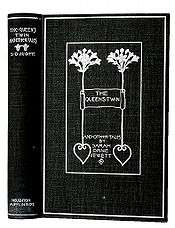

- The Queen's Twin and Other Stories, Houghton-Mifflin, 1899

- The Tory Lover, Houghton-Mifflin, 1901

- An Empty Purse: A Christmas Story, privately printed, 1905

References

- ↑ Aubrey E. Plourde, A Woman's World: Sarah Orne Jewett's Regionalist Alternative, scholarship.rollins.edu, Retrieved December 19, 2013. In his Sarah Orne Jewett, F.O. Matthiessen wrote "The distinction and refinement of Sarah Jewett's prose came out of an America which, with its Tweed rings and grabbing Trusts, its blatantly moneyed New York and squalid frontier towns, seemed most lacking in just these qualities. They are essentially a feminine contribution, and the fact that they now appear more valuable than anything the men of her generation could produce is a symptom of what had happened to New England since the Civil War. The vigorous genius of the earlier golden day had left no sons. Emily Dickinson is the heir of Emerson's spirit, and Sarah Jewett the daughter of Hawthorne's style." F.O. Matthiessen, Sarah Orne Jewett, public.coe.edu, Retrieved December 19, 2013

- ↑ Her mother's family, the Gilmans, were among the most prominent settlers of Exeter, New Hampshire. Sarah's great-grandfather, James Orne, was descended from the Orne family of Dover, New Hampshire, who were among the first settlers of Dover. The Jewetts had emigrated from Yorkshire to Boston in 1638 and later founded Rowley, Massachusetts. From there they moved on to Portsmouth, New Hampshire just after the Revolutionary War.

- ↑ Teacher, Janet Bukovinsky (1994). Women of Words. Frankfort, Germany: Courage Books. p. 43. ISBN 9781561387694.

- ↑ Richard Cary, Sarah Orne Jewett (New Haven, CT: Twayne, 1962), 21.

- ↑ For instance, one stroll she found "neighborly with the hop-toads and with a joyful robin who was sitting on a corner of the barn, and I became very intimate with a great poppy which had made every arrangement to bloom as soon as the sun came up." Fields, ed. Letters of Sarah Orne Jewett, 45.

- ↑ The Country of the Pointed Firs at The Sarah Orne Jewett Text Project.

- ↑ "Two Unidentified Newspaper Pieces on Olive Raynes" at The Sarah Orne Jewett Text Project.

- 1 2 3 Margaret A. Amstutz, "Jewett, Sarah Orne," American National Biography Online, February 2000; Rachel Smith Matzko, "The Religious Attitudes of Sarah Orne Jewett, M. A. thesis, Clemson University, 1979.

- ↑ Cary, 29. Jewett wrote to a teenage reader: "I cannot tell you just where Dunnet Landing is except that it must be somewhere 'along shore' between the regions of Tenants Harbor and Boothbay, or it might be farther to the eastward in a country that I know less well." Sarah Orne Jewett Text Project.

- ↑ Cary, 12, 29.

- ↑ Oxford Companion to American Literature, 382

- ↑ Margaret A. Amstutz, "Jewett, Sarah Orne," American National Biography Online, Feb. 2000; Website of Historic New England

- ↑ See, for instance, Dottie Webb,"Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Adams Fields: Boston Marriage and Cultural Nexus," There is a more cautious appraisal on the website of the Sarah Orne Jewett Text Project. Fields was fifteen years older than Jewett, but they had similar tastes in "reading, writing, and the arts." Richard Cary, Sarah Orne Jewett (New Haven, CT: Twayne, 1962), 25.

- ↑ Sarah Orne Jewett: Novels and Stories (New York: Library of America, 1994), 924, 927

Further reading

- Bell, Michael Davitt, ed. Sarah Orne Jewett, Novels and Stories (Library of America, 1994) ISBN 978-0-940450-74-5

- Berthoff, Warner (1971). "Jewett, Sarah Orne". In James, E.T.; James, J.W. Notable American Women: 1607-1950. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Blanchard, Paula. Sarah Orne Jewett: Her World and Her Work (Addison-Wesley, 1994) ISBN 0-201-51810-4

- Church, Joseph. Transcendent Daughters in Jewett's Country of the Pointed Firs (Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 1994) ISBN 0-8386-3560-1

- Renza, Louis A. "A White Heron" and The Question of Minor Literature (University of Wisconsin Press, 1985) ISBN 978-0-299-09964-0

- Sherman, Sarah W. Sarah Orne Jewett, an American Persephone (University Press of New England, 1989) ISBN 978-0-87451-484-1

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sarah Orne Jewett |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Sarah Orne Jewett |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sarah Orne Jewett. |

- Works by Sarah Orne Jewett at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Sarah Orne Jewett at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Sarah Orne Jewett at Internet Archive

- Works by Sarah Orne Jewett at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Sarah Orne Jewett Text Project

- The Country of Pointed Firs at Bartleby.com

- Sarah Orne Jewett's Literature Online

- PAL

- Index entry for Sarah Orne Jewett at Poet's Corner

- Sarah Orne Jewett House Museum, South Berwick, Maine

- Sarah Orne Jewett's "A White Heron"