Santiago Ramón y Cajal

| Santiago Ramón y Cajal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1 May 1852 Petilla de Aragón, Navarre, Spain |

| Died |

17 October 1934 (aged 82) Madrid, Spain |

| Known for | The father of modern Neuroscience |

| Signature | |

| |

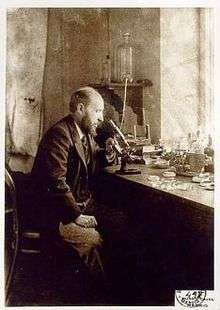

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (Spanish: [sanˈtjaɣo raˈmon i kaˈxal]; 1 May 1852 – 17 October 1934) was a Spanish pathologist, specializing in neuroanatomy, particularly the histology of the central nervous system. He won the Nobel prize in 1906. His original investigations of the microscopic structure of the brain made him a pioneer of modern neuroscience. Hundreds of his drawings illustrating the delicate arborizations of brain cells are still in use for educational and training purposes.[1]

Biography

Santiago Ramón y Cajal was born 1 May 1852 in the town of Petilla de Aragón, Navarre, Spain. His father was an anatomy teacher

As a child he was transferred many times from one school to another because of behavior that was declared poor, rebellious, and showing an anti-authoritarian attitude. An extreme example of his precociousness and rebelliousness at the age of eleven is his 1863 imprisonment for destroying his neighbor's yard gate with a homemade cannon.[2]

He was an avid painter, artist, and gymnast, but his father neither appreciated nor encouraged these abilities, even though these artistic talents would contribute to his success later in life. In order to tame the unruly character of his son, his father apprenticed him to a shoemaker and barber. "To try and give his son much-needed discipline and stability, Don Justo apprenticed him out to a barber".[3] He was well known for his pugnacious attitude as he worked.

Over the summer of 1868, his father hoped to interest his son in a medical career, and took him to graveyards to find human remains for anatomical study. Sketching bones was a turning point for him and subsequently, he did pursue studies in medicine.[4]:207

Ramón y Cajal attended the medical school of the University of Zaragoza, where his father was an anatomy teacher. He graduated in 1873, aged 21. After a competitive examination, he served as a medical officer in the Spanish Army. He took part in an expedition to Cuba in 1874–75, where he contracted malaria and tuberculosis.[5] In order to heal, he visited the Panticosa spa-town in the Pyrenees.

After returning to Spain, he received his doctorate in medicine in Madrid in 1877. In 1879, he became the director of the Zaragoza Museum, and he married Silveria Fañanás García, with whom he had four daughters and three sons. Ramón y Cajal worked at the University of Zaragoza until 1883, when he was awarded the position of anatomy professor of the University of Valencia.[5] His early work at these two universities focused on the pathology of inflammation, the microbiology of cholera, and the structure of epithelial cells and tissues.

In 1887 Ramón y Cajal moved to Barcelona for a professorship.[5] There he first learned about Golgi's method, a cell staining method which uses potassium dichromate and silver nitrate to (randomly) stain a few neurons a dark black color, while leaving the surrounding cells transparent. This method, which he improved, was central to his work, allowing him to turn his attention to the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), in which neurons are so densely intertwined that standard microscopic inspection would be nearly impossible. During this period he made extensive detailed drawings of neural material, covering many species and most major regions of the brain.

In 1892, he became professor at Madrid.[5] in 1899 he became director of the Instituto Nacional de Higiene – translated as National Institute of Hygiene , and in 1922 founder of the Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas – translated as the Laboratory of Biological Investigations , later renamed to the Instituto Cajal, or Cajal Institute.[5]

He died in Madrid on October 17, 1934, at the age of 82,[6] continuing to work even on his deathbed.[5][7]

Political and religious views

In 1877, the 25 year old Cajal joined a Masonic lodge.[8]:156 John Brande Trend wrote in 1965, that Cajal "was a liberal in politics, an evolutionist in philosophy, an agnostic in religion".[9]

Nonetheless, Cajal used the term soul "without any shame".[10] He was said to later have regretted having left organized religion,[8]: 343 Ultimately, he became convinced of a belief in God as a creator, as stated during his first lecture before the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences.[11][12]

Discoveries and theories

Ramón y Cajal made several major contributions to neuroanatomy.[4] He discovered the axonal growth cone, and demonstrated experimentally that the relationship between nerve cells was not continuous, but contiguous.[4] This provided definitive evidence for what Heinrich Waldeyer coined the term neuron theory as opposed to the reticular theory). This is now widely considered the foundation of modern neuroscience.[4]

He was an advocate of the existence of dendritic spines, although he did not recognize them as the site of contact from presynaptic cells. He was a proponent of polarization of nerve cell function and his student, Rafael Lorente de Nó, would continue this study of input-output systems into cable theory and some of the earliest circuit analysis of neural structures.

By producing excellent depictions of neural structures and their connectivity and providing detailed descriptions of cell types he discovered a new type of cell, which was subsequently named after him, the interstitial cell of Cajal (ICC).[13] This cell is found interleaved among neurons embedded within the smooth muscles lining the gut, serving as the generator and pacemaker of the slow waves of contraction which move material along the gastrointestinal tract, mediating neurotransmission from motor neurons to smooth muscle cells.

In his 1894 Croonian Lecture, Cajal suggested (in an extended metaphor) that cortical pyramidal cells may become more elaborate with time, as a tree grows and extends its branches.

He devoted a considerable amount of time studying hypnosis which he used to help his wife during labor and parapsychological phenomena. A book he had written on these topics was lost during the Spanish Civil War.

Cajal's efforts to improve the state of scientific research and education in Spain were part of a broader preoccupation with Regenerationism among Spanish intellectuals.

Distinctions

Ramón y Cajal received many prizes, distinctions, and societal memberships during his scientific career, including honorary doctorates in medicine from Cambridge University and Würzburg University and an honorary doctorate in philosophy from Clark University.[5] The most famous distinction he was awarded was the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906, together with the Italian scientist Camillo Golgi "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system".[5] This caused some controversy because Golgi, a staunch supporter of reticular theory, disagreed with Ramón y Cajal in his view of the neuron doctrine.

Publications

He published more than 100 scientific works and articles in Spanish, French and German. Among his most notable works were:[5]

- Rules and advice on scientific investigation

- Histology

- Degeneration and regeneration of the nervous system

- Manual of normal histology and micrographic technique

- Elements of histology

A list of his books includes:

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1905) [1890]. Manual de Anatomia Patológica General (Handbook of general Anatomical Pathology) (in Spanish) (fourth ed.).

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago; Richard Greeff (1894). Die Retina der Wirbelthiere: Untersuchungen mit der Golgi-cajal'schen Chromsilbermethode und der ehrlich'schen Methylenblaufärbung (Retina of vertebrates) (in German). Bergmann.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago; L. Azoulay (1894). Les nouvelles idées sur la structure du système nerveux chez l'homme et chez les vertébrés' ('New ideas on the fine anatomy of the nerve centres). (in French). C. Reinwald.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago; Johannes Bresler; E. Mendel (1896). Beitrag zum Studium der Medulla Oblongata: Des Kleinhirns und des Ursprungs der Gehirnnerven (in German). Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1898). "Estructura del quiasma óptico y teoría general de los entrecruzamientos de las vías nerviosas. (Structure of the Chiasma opticum and general theory of the crossing of nerve tracks)" [Die Structur des Chiasma opticum nebst einer allgemeine Theorie der Kreuzung der Nervenbahnen (German, 1899, Verlag Joh. A. Barth)]. Rev. Trim. Micrográfica (in Spanish). 3: 15–65.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1899). Comparative study of the sensory areas of the human cortex. p. 85. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1899–1904). Textura del sistema nervioso del hombre y los vertebrados. (in Spanish). Madrid.

- ——. Histologie du système nerveux de l'homme & des vertébrés (in French) – via Internet Archive.

- ——. Texture of the Nervous System of Man and the Vertebrates.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1906). Studien über die Hirnrinde des Menschen v.5 (Studies about the meninges of man) (in German). Johann Ambrosius Barth.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1999) [1897]. Advice for a Young Investigator. Translated by Neely Swanson and Larry W. Swanson. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-68150-1.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1937). Recuerdos de mi Vida (in Spanish). Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 84-206-2290-7.

In 1905, he published five science-fiction stories called "Vacation Stories" under the pen name "Dr. Bacteria".[14]

In society and culture

The asteroid 117413 Ramonycajal has been named in his honor.

In 2014, the National Institutes of Health exhibited original Cajal drawings in its Neuroscience Research Center.[15]

An exhibition called The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal travelled through the US beginning 2017 at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis ending April 2019 at the Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.[16]

A short documentary by REDES is available on YouTube[17] Spanish public television filmed a biopic series to commemorate his life.

Gallery of drawings

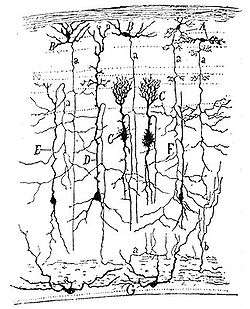

Drawing of the neural circuitry of the rodent hippocampus. Histologie du Système Nerveux de l'Homme et des Vertébrés, Vols. 1 and 2. A. Maloine. Paris. 1911

Drawing of the neural circuitry of the rodent hippocampus. Histologie du Système Nerveux de l'Homme et des Vertébrés, Vols. 1 and 2. A. Maloine. Paris. 1911 Drawing of the cells of the chick cerebellum, from "Estructura de los centros nerviosos de las aves", Madrid, 1905

Drawing of the cells of the chick cerebellum, from "Estructura de los centros nerviosos de las aves", Madrid, 1905 Drawing of a section through the optic tectum of a sparrow, from "Estructura de los centros nerviosos de las aves", Madrid, 1905

Drawing of a section through the optic tectum of a sparrow, from "Estructura de los centros nerviosos de las aves", Madrid, 1905 From "Structure of the Mammalian Retina" Madrid, 1900

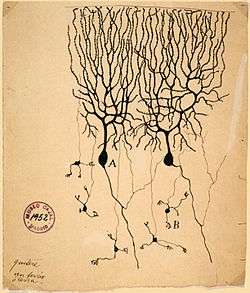

From "Structure of the Mammalian Retina" Madrid, 1900 Drawing of Purkinje cells (A) and granule cells (B) from pigeon cerebellum by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 1899. Instituto Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain

Drawing of Purkinje cells (A) and granule cells (B) from pigeon cerebellum by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 1899. Instituto Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain Drawing of Cajal-Retzius cells, 1891

Drawing of Cajal-Retzius cells, 1891 Drawn in 1899, taken from the book "Comparative study of the sensory areas of the human cortex"

Drawn in 1899, taken from the book "Comparative study of the sensory areas of the human cortex"

See also

Notes

- ↑ "History of Neuroscience". Society for Neuroscience. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Recuerdos de mi Vida Volume I, Chapter X, Madrid Imprenta y Librería de N. Moya, Madrid 1917, online at Instituto Cervantes (Spanish)

- ↑ A Mind for Numbers. Tarcher Penguin. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-399-16524-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Finger, Stanley (2000). "Chapter 13: Santiago Ramon y Cajal. From nerve nets to neuron doctrine". Minds behind the brain: A history of the pioneers and their discoveries. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 197–216. ISBN 0-19-508571-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Nobel lectures, Physiology or Medicine 1901-1921. Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Company. 1967. Retrieved 2013-01-29.

- ↑ Sherrington, C. S. (1935). "Santiago Ramon y Cajal. 1852-1934". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 1 (4): 424–441. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1935.0007.

- ↑ Yuste, Rafael (21 April 2015). "The discovery of dendritic spines by Cajal". Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. 9 (18). PMC 4404913

. PMID 25954162. doi:10.3389/fnana.2015.00018.

. PMID 25954162. doi:10.3389/fnana.2015.00018. - 1 2 José María López Piñero, "Santiago Ramón y Cajal", Universita de València

- ↑ John Brande Trend (1965). The Origins of Modern Spain. Russell & Russell. p. 82.

Cajal was a liberal in politics, an evolutionist in philosophy, an agnostic in religion...

- ↑ Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj (2010). Marcelo Suarez-Orozco, ed. Educating the Whole Child for the Whole World: The Ross School Model and Education for the Global Era. NYU Press. p. 165. ISBN 9780814741405.

In that sense, it was interesting to learn that Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the great pioneer of modern neuroanatomy, was agnostic, but still used the term soul without any shame.

- ↑ DISCURSO DEL SR. D. SANTIAGO RAMÓN Y CAJALTEMA: FUNDAMENTOS RACIONALES Y CONDICIONES TÉCNICAS DE LAINVESTIGACIÓN BIOLÓGICA Sesquicentenario de Santiago Ramon y Cajal], 23 pages, p. 39-40: a los que te dicen que la Ciencia apaga toda poesía, secando las fuentes del sentimiento y el ansia de misterio que late en el fondo del alma humana, contéstales que á la vana poesía del vulgo, basada en una noción errónea del Universo, noción tan mezquina como pueril, tú sustituyes otra mucho más grandiosa y sublime, que es la poesía de la verdad, la incomparable belleza de la obra de Dios y de las leyes eternas por Él establecidas. Él acierta exclusivamente a comprender algo de ese lenguaje misterioso que Dios ha escrito en los fenómenos de la Naturaleza; y a él solamente le ha sido dado desentrañar la maravillosa obra de la Creación para rendir a la Divinidad uno de los cultos más gratos y aceptos a un Supremo entendimiento, el de estudiar sus portentosas obras, para en ellas y por ellas conocerle, admirarle y reverenciarle. [English Translation: P. 39-40: To those who tell you that Science quenches all poetry, drying up the sources of feeling and the longing for mystery that pulses in the depths of the human soul, tell them that in the vain poetry of the people, based on an erroneous notion of Universe, as petty as it is puerile, you substitute a much more grandiose and sublime one, which is the poetry of truth, the incomparable beauty of the work of God and the eternal laws established by him. He is only able to understand something of that mysterious language that God has written in the phenomena of Nature; And he has only been able to unravel the wonderful work of Creation to render to the Divinity one of the most grateful and accepted cults to a supreme understanding, to study his portentous works, for them and for them to know, to admire and to revere him ]

- ↑ "Las creencias de Darwin y Cajal | Amigos de Serrablo". Serrablo.org. 2009-03-31. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ↑ "FANZCA part I notes on the Autonomic Nervous System". Anaesthetist.com. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ↑ http://www.lablit.com/article/226/

- ↑ NIH Exhibits Original Cajal Neuroscience Drawings Intramural Research Program at the National Institutes of Health (NIH IRP), YouTube, 2:16 min

- ↑ Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal The Weisman Art Museum, retrieved 9 August 2017

- ↑ Documental sobre Santiago Ramón y Cajal en Redes YouTube, 34 min, Sep 22, 2012. (Spanish)

References

- Everdell, William R. (1998). The First Moderns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-22480-5.

- Mazzarello, Paolo (2010). Golgi: A Biography of the Founder of Modern Neuroscience. Translated by Aldo Badiani and Henry A. Buchtel. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195337846.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santiago Ramón y Cajal. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Santiago Ramón y Cajal |

- Fishman, R. S. (2007). "The Nobel Prize of 1906". Archives of Ophthalmology. 125 (5): 690–694. PMID 17502511. doi:10.1001/archopht.125.5.690. (Review of the work of the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine winners Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal)

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906 Nobel Prizes and Laureates. n.d.

- Marina Bentivoglio Life and discoveries of Cajal Nobel Prizes and Laureates, 20 April 1998

- Cajal's Láminas ilustrativas Centro Virtual Cervantes

- Javier de Felipe Brief overview of Ramón y Cajal's career www.psu.edu The Pennsylvania State University, 1998