Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

| Santa Maria del Popolo S. Mariæ de Populo (in Latin) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°54′41″N 12°28′35″E / 41.911389°N 12.476389°ECoordinates: 41°54′41″N 12°28′35″E / 41.911389°N 12.476389°E |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Rite | Latin Rite |

| Municipality | Municipio I |

| District | Campo Marzio |

| Province | Diocese of Rome |

| Country | Italy |

| Year consecrated | 1477 |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Basilica minor, parish church (1561), titular church (1587) |

| Status | Active |

| Leadership | Stanislaw Dziwisz |

| Website | Santa Maria del Popolo |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Andrea Bregno, Donato Bramante, Gian Lorenzo Bernini |

| Architectural type | basilica |

| Architectural style | Renaissance, Baroque |

| Founder | Pope Paschal II (1099) |

| Groundbreaking | 1472 |

| Completed | 1477 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | W |

| Dome(s) | 3 |

| Spire(s) | 1 |

The Parish Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo (Italian: Basilica Parrocchiale Santa Maria del Popolo) is a titular church and a minor basilica in Rome run by the Augustinian order. It stands on the north side of Piazza del Popolo, one of the most famous squares in the city. The church is hemmed in between the Pincian Hill and Porta del Popolo, one of the gates in the Aurelian Wall as well as the starting point of Via Flaminia, the most important route from the north. Its location made the basilica the first church for the majority of travellers entering the city. The church contains works by several famous artists, such as Raphael, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Caravaggio, Alessandro Algardi, Pinturicchio, Andrea Bregno, Guillaume de Marcillat and Donato Bramante.

History

Foundation legend

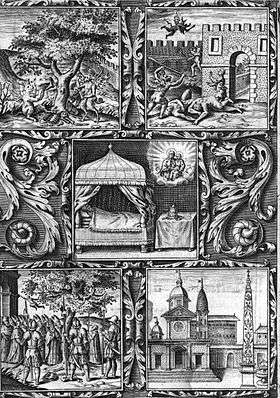

The well-known foundation legend of Santa Maria del Popolo revolves around the evil memory of Emperor Nero and Pope Paschal II cleansing the area from this malicious legacy. As the story goes the emperor was buried after his demise at the foot of the Pincian Hill in the mausoleum of his paternal family, the Domitii Ahenobarbi. The sepulchre was later buried under a landslide and a huge walnut tree grew on the ruins that ″was so tall and sublime that no other plant exceeded it in any ways.″ The towering walnut soon became the haunt of a multitude of vicious demons harassing the inhabitants of the area and also the travelers arriving in the city from the north through Porta Flaminia: ″some were being frightened, possessed, cruelly beaten and injured, others almost strangled, or miserably killed.″ The actions of the demonic crowd endangered an important access of the city and also upset the entire population, causing serious concern to the newly elected pontiff, Paschal II who ″saw the flock of Christ committed to his watch, becoming prey to the infernal wolves.″[1]

The Pope fasted and prayed for three days and at the end of that period, exhausted, he received a vision in his dream from the Blessed Virgin Mary who gave him detailed instructions to free the city from that scourge. On the Thursday after the third Sunday of Lent in 1099, the Pope summoned the whole clergy and all the inhabitants of Rome and set up an impressive procession that, with the crucifix at its head, went along the urban stretch of Via Flaminia until it reached the infested place. There the Pope performed the rite of exorcism and then struck a determined blow at the root of the walnut tree. The infernal creatures erupted from their haunt madly screaming. When the whole tree was removed the remains of the emperor were discovered among the ruins and the Pope ordered to throw them into the waves of the Tiber.

Finally liberated from the malevolent presence, that corner of Rome could be devoted to Christian worship and the Pontiff, at the sound of praise songs, placed the first stone of an altar on the site of the horrible tree. This was incorporated into a simple chapel which was completed in three days. The construction was celebrated with particular solemnity: the Pope consecrated the small sanctuary in the presence of a large crowd, accompanied by ten cardinals, four archbishops, ten bishops and other prelates. He also granted the chapel many relics and dedicated it to the Blessed Virgin.

Origins

The legend was recounted by an Augustinian friar, Giacomo Alberici in his treatise about the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo which was published in Rome in 1599 and translated into Italian the next year.[2] Another Augustinian, Ambrogio Landucci rehashed the same story in his book about the origins of the basilica in 1646.[3] The legend has been retold several times ever since with slight changes in collections of Roman curiosities, scientific literature and guidebooks. An example of the variations could be found in Ottavio Panciroli's book which claimed that the demons inhabiting the tree took the form of black crows.[4] It is not known how far back the tradition goes but in 1726 it still existed in the archive of Santa Maria del Popolo a catalogue of the holy relics of the church written in 1426 which contained a (lost) version of the ″miracle of the walnut tree″. This was allegedly copied from an even more more ancient tabella at the main altar.[5] In the 15th century the story was already popular enough to be recounted by various German sources like Nikolaus Muffel's Description of Rome (1452)[6] or The Pilgrimage of Arnold Von Harff (1497).[7]

The factual basis of the legend is weak. Nero was indeed buried in the mausoleum of his paternal family but Suetonius in his Life of Nero says that ″the family tomb of the Domitii [was] on the summit of the Hill of Gardens, which is visible from the Campus Martius.″ The location of the mausoleum was therefore somewhere on the higher north-west slopes of the Pincian Hill and certainly not at the foot of it where the church stands.[8]

The foundation of the chapel by Pope Paschal II was maybe part of an effort to restore the safety of the area around Porta Flaminia which was ouside the inhabited core of medieval Rome and certainly infested with bandits. Another possible source of inspiration for the legend could have been the well-documented revenge of Pope Paschal II on the body of his opponent, Antipope Clement III. The pope seized the city of Civita Castellana, had Clement’s cadaver exhumed from his tomb, and ordered to thrown it into the Tiber. Clement III was the protégée of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV who was often called "Nero" by the papal party.[9]

Name

The name del Popolo ("of the people") was most probably derived from populus meaning large rural parish in medieval Latin. In this case the name refers to the first suburban settlement around Via Flaminia that was formed after the chapel had been built in this previously deserted part of Campus Martius.[10] Others think the denomination implied that the people of Rome were saved from the demonic scourge or it came from the Latin word pōpulus, meaning poplar. The demonic tree was a huge walnut but there might have been poplar trees growing on ancient tombs in the locality. The name S. Maria ad Flaminiam appeared in some 15th-century documents.

Early history

The name of Santa Maria del Popolo is missing in the catalogue of the churches of Rome which was written by Cencio Camerario in 1192. Later tradition held that the miraculous image of Our Lady, painted by St. Luke himself, was moved to the church by Pope Gregory IX from the Sancta Sanctorum in the Lateran. This happened after a flood of the Tiber - probably the great flood in 1230 - caused a horrible plague in the city. The pope convoked the cardinals, the whole clergy and the people of Rome and the icon was transferred with a solemn procession to Santa Maria del Popolo. After that the plague ceased and the tranquility of the city was restored.[11] The Madonna del Popolo has certainly remained one of the most popular Marian icons through the centuries, attracted many pilgrims and assured a greater role to the geographically still remote church.

The early history of Santa Maria del Popolo is almost unknown because the archives of the church were dispersed during the Napoleonic era and few documents survived from before 1500. The first references in archival sources are from the 13th century. The Catalogue of Paris (compiled around 1230 or 1272-76) listing the churches of Rome already contains the name of Santa Maria de Populo.[12] There may have been a small Franciscan community living by the church until around 1250 but it is possible that they stayed there only temporarily.[13]

The Augustinians

In the middle of the 13th century the church was given to the Order of Saint Augustine which has maintained it ever since. The Augustinians were a new mendicant order established under the guidence of Cardinal Riccardo Annibaldi, probably the most influential member of the Roman Curia at the time. Annibaldi was appointed corrector and provisor of the Tuscan hermits by Pope Innocent IV in December 1243. The cardinal convened a meeting to Santa Maria del Popolo for the delegates of the hermitic communities where they declared their union and the foundation of the new order that the Pope confirmed with the bull Pia desideria on 31 March 1244.[14]

A few years later a community of friars was established by the church and the Franciscans were compensated for their loss with the monastery of Ara Coeli. This probably happened in 1250 or 1251. The so-called Grand Union that integrated various other hermitic communities with the Tuscans by the order of Pope Alexander IV was also established on the general chapter held in Santa Maria del Popolo under the supervision of Cardinal Annibaldi in March 1256. The strong connection between the Annibaldi family and the church was attested on an inscription that mentioned two noble ladies of the family who set up some kind of marble monument in the basilica in 1263.[15] The Catalogue of Turin (c. 1320) stated that the monastery had 12 friars from the order of the hermits at the time.

In the 15th century the friary of Santa Maria del Popolo joined the observant reform movement that tried to restore the original purity of monastic life. The general chapter of the Augustinian observants in May 1449 established five separate congregations for the observant friars in Italy. That of Rome-Perugia was sometimes named after Santa Maria del Popolo although the monastery never had an official position as mother-house. In 1472 the friary was given over by Pope Sixtus IV to the Lombard Congregation, the most important and populous of all, and it became its Roman headquarter and the seat of its procurator general (ambassador) at the Roman Curia.[16]

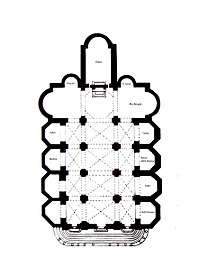

The Sistine rebuilding

Soon after its transfer to the prestigious Lombard Congregation Santa Maria del Popolo was reconstructed between 1472 and 1477 on the orders of Pope Sixtus IV. This was part of the ambitious urban renovation program of the pope who presented himself as Urbis Restaurator of Rome.[17] The medieval church was entirely demolished and a new three-nave, Latin cross shaped basilica was built with four identical chapels on both sides, an octagonal dome above the crossing and a tall Lombard style bell-tower at the end of the right arm of the transept. The result of this reconstruction was an early and excellent example of Italian Renaissance architecture in Rome. In spite of the many changes, that occurred during the later centuries, the basilica essentially kept its Sistine form until today.

The architect or architects of this innovative project remain unknown due to the lack of contemporary sources. Giorgio Vasari in his Lives attributed all the important papal projects in Rome during Sixtus IV to a Florentine, Baccio Pontelli including the basilica and monastery of Santa Maria del Popolo. Modern researchers deemed this claim highly dubious and proposed other names among them Andrea Bregno, a Lombard sculptor and architect whose workshop certainly received important commissions in the basilica. The fundamental differences between the façade and the interior suggest that maybe more than one architect was working on the different parts of the building.[18]

The year of completion is indicated on the inscriptions above the side doors of the façade. The one on the left reads "SIXTUS·PP·IIII·FVNDAVIT·1477", the other on the right reads "SIXTUS·PP·IIII·PONT·MAX·1477". Jacopo da Volterra recorded in his diary that the pope visited the church that "he rebuilt from the ground up a few years ago" in 1480. The pope was strongly attached to the church, he went there to pray every Saturday and celebrated mass in the papal chapel every year on September 6, the feast of the Nativity of the Virgin. On 2 June 1481 when the news about the death of Mehmed the Conqueror was confirmed, the pope went to the Vespers at Santa Maria del Popolo in thanksgiving with the cardinals and the ambassadors. Another occasion when the pope celebrated an important event in the basilica was the victory of the papal troops against the Neapolitans at Campomorto on 21 August 1482.

The reconstruction also had a symbolic meaning that the evil walnut tree of Nero was supplanted by the beneficient oak of the della Rovere. The papal coats of arms were placed above the door and the vault as "symbols of eternal happiness and protection from lightning", as Landucci explained praising the transposition of the two trees.[19] Another important aspect of the Sistine reconstruction was that it made the basilica - the first church for the pilgrims arriving in Rome from the North - a dynastic monument of the della Rovere family. This was reinforced by relatives of the pope and other personages of his court who bought chapels in the church and built funeral monuments. "Santa Maria del Popolo became a place to unite visually the universal domination of the church with the della Rovere, a totemic symbol that would associate the della Rovere with Rome and allowed them to co-opt its magnificience and glory", claimed Lisa Passaglia Bauman.[20]

The new high altar for the icon of the Madonna was commissioned by Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, the nephew of the pope, or Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia in 1473. Another relative, Cardinal Domenico della Rovere bought two chapels on the right side. He transformed the first one into a funeral chapel and sold the other one to Cardinal Jorge da Costa in 1488. The next papal family, the Cybos furnished the second chapel on the right in the 1490s, and also the third chapel on the left, while the third chapel on the right went to another cardinal-nephew of Pope Sixtus, Girolamo Basso della Rovere. In the first chapel on the left a confidant of the pope, Bishop Giovanni Montemirabile was buried in 1479. Another confidant, Cardinal Giovanni Battista Mellini was buried in the third chapel on the left after his death in 1478. The two artists most closely associated with this period of the church were the sculptor Andrea Bregno and the painter Pinturicchio.

The basilica retained its importance in the Borgia era. When the Pope's son, the Duke of Gandia was murdered in June 1497, the body was laid in state in the basilica and buried in the Borgia Chapel. Other members of the family and their circle were also buried in the transept, including Vannozza dei Cattanei, the former mistress of Alexander VI in 1518, and the pope's secretary and physician, Ludovico Podocataro in 1504.

The Julian extension

With the election of another Della Rovere cardinal, Julius II in 1503, the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo again became the favourite church of the reigning pope. Julius was strongly devoted to the icon of Madonna del Popolo and he was as strongly devoted to increasing the glory of his dynasty. For these reasons he took up the work of his uncle and built a spacious new choir between 1505 and 1510 behind the main altar. The project was entrusted to his favourite architect, Donato Bramante. The choir was built in High Renaissance style, and it was decorated with the frescoes of Pinturicchio on the sail vault and the stained glass windows of Guillaume de Marcillat. It was also used as a mausoleum where Andrea Sansovino created two monumental tombs for Cardinal Girolamo Basso della Rovere (†1507), the favourite cousin of the pope, and Cardinal Ascanio Sforza (†1505), his former rival.

There was another important commission for Raphael. He painted the Madonna of the Veil, a portrayal of the Holy Family (c. 1508), and the Portrait of Pope Julius II (c. 1511) to be displayed at the church. There are references from the 1540s and later that the pair of highly prestigious votive images were occasionally hanged on the pillars for feast days but otherwise they were probably kept in the sacristy.[21] Unfortunately in 1591 both paintings were removed by Paolo Emilio Sfondrati from the church and later sold off.

Julius II granted assent for the wealthy Sienese banker, Agostino Chigi, who was adopted into the Della Rovere family, to build a mausoleum replacing the second identical side chapel on the left in 1507. The chapel was dedicated to the Virgin of Loreto whose cult was ardently promoted by the Della Rovere popes. The Chigi Chapel was designed by Raphael and it was partially completed in 1516 but remained unfinished for a very long time. This ambitious project created a strong connection between the basilica and the Chigis that extended well into the next century.

In the Julian era the church became again the location of important papal ceremonies. The pope launched his first campaign here on 26 August 1506 and when he returned to Rome after the successful Northern Italian war, he spent the night of 27 March 1507 in the convent of Santa Maria del Popolo. On the next day Julius celebrated High Mass on Palm Sunday in the church that was decorated with fronds of palm and olive branches. The ceremony was followed by a triumphal entry into the city. On 5 October 1511 the Holy League against France was solemnly proclaimed in the basilica. On 25 November 1512 the alliance of the pope with Emperor Maximilian I was also announced in this church in the presence of fifty-two diplomatic envoys and fifteen cardinals. The pope also visited the Madonna del Popolo for private reasons like when he prayed for the recovery of his favourite nephew, Galeotto Franciotti della Rovere in early September 1508.

Luther's visit

Luther's journey to Rome as young Augustinian monk is a famous episode of his life period before the Reformation. Although his stay in the city became the stuff of legends, the circumstances and details of this journey are surprisingly murky due to a scarcity of authentic sources. Even the traditional date (1510/11) was questioned recently when Hans Schneider suggested that the trip happened a year later in 1511/12.[22]

What is certain that the journey was connected to a feud between the Observant and the Conventual monasteries of the Augustinian Order in Germany and their proposed union. According to the traditional dating Luther arrived in Rome between 25 December 1510 and January 1511. His biographer, Heinrich Böhmer assumed that the young observant monk stayed in the monastery of Santa Maria del Popolo. This assumption was disputed by newer biographers who argued that the tense relationship between the Lombardian Congregation and the administration of the Augustinian order made the monastery of Santa Maria del Popolo an unsuitable lodging for Luther who tried to win a favour at the leaders of his order.[23] Be that as it may, Luther, who spent four weeks in Rome, certainly visited the only observant Augustinian monastery in the city and its famous pilgrimage church that was the favourite of the reigning pope.

The parish

After the Della Rovere era, the basilica lost its prominent role as a papal church but it remained one of the most important pilgrimage churches in the city. This was shown on 23 November 1561 when Pope Pius IV held a solemn procession from St. Peter's to the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo on the occasion of reopening the Council of Trent. Building works went on in the Chigi Chapel in a slow pace until the 1550s. The last important Renaissance addition was the Theodoli Chapel between 1555 and 1575 with rich stucco and fresco decoration by Giulio Mazzoni.

At the same time the basilica became a parish church when Pope Pius IV created the Parish of St. Andrew "outside Porta Flaminia" with the motu proprio Sacri apostolatus on 1 January 1561 and united it in perpetuity with the Augustinian priory. The care of the new parish was entrusted to the friars and Pope Pius V moved the seat of the parish to Santa Maria del Popolo. The parish still exists encompassing a large area comprising the southern part of the Flaminio district, the Pincian Hill and the northernmost part of the historic centre around Piazza del Popolo.[24] The basilica was made a titular church on 13 April 1587 by Pope Sixtus V with the apostolic constitution Religiosa. The first cardinal priest of the titulus was Cardinal Tolomeo Gallio. Pope Sixtus V also enhanced the liturgical importance of the basilica elevating it for the rank of station church in his 13 February 1586 bull which revived the ancient custom of the Stations. (Although this role was lost in modern times.)

In April 1594 Pope Clement VIII ordered the removal of the tomb of Vannozza dei Cattanei, the mistress of Alexander VI, from the basilica because the memory of the Borgias was a stain on the history of the Catholic Church for the reformed papacy and the visible traces had to disappear.[25]

Caravaggio and the Chigi reconstruction

On 8 July 1600 Monsignor Tiberio Cerasi, Treasurer-General of Pope Clement VIII purchased the patronage right of the old Foscari Chapel in the left transept and soon demolished it. The new Cerasi Chapel was designed by Carlo Maderno between 1601 and 1606, and it was decorated with two large Baroque canvases by Caravaggio, the Conversion of Saint Paul and the Crucifixion of Saint Peter. These are the most important works of art in the basilica, and unrivalled high points of Western art. A third painting is also significant, the Assumption of the Virgin by Annibale Carracci which was set on the altar.

During the first half of the 17th century there were no other significant building works in the basilica but many Baroque funeral monuments were erected in the side chapels and the aisles, the most famous among them the tomb of Cardinal Giovanni Garzia Mellini by Alessandro Algardi from 1637-38. Two noteworthy fresco cycles were added by Giovanni da San Giovanni in the Mellini Chapel, that the owner family restored in the 1620s, and by Pieter van Lint in the Chapel of Innocenzo Cybo in the 1630s.

A new wave of construction began when Fabio Chigi became the cardinal priest of the church in 1652. He immediately began the reconstruction of the neglected family chapel which was embellished by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. In 1655 Chigi was elected pope under the name Alexander VII. He repeatedly came to see how the work progressed; there was a papal visit on 4 March 1656, 10 February and 3 March 1657. Due to this personal supervision the project was speedily completed by the middle of 1657 but the last statue of Bernini was only put in place in 1661.

In the meantime the pope entrusted Bernini with the task of modernizing the old basilica in contemporary Baroque style. In March 1658 Alexander VII inspected the work in the company of the architect. This proved to be a significant rebuilding that altered the character of the quattrocento church. The façade was changed, larger windows were opened in the nave, statues, frescos and stucco decorations were added in the interior and a new main altar was erected. Two side altars and organ lofts were built in the area of the transept where the old Borgia Chapel was demolished. Chigi coat-of-arms, symbols and inscriptions celebrated the glory of the pope everywhere.

With the Berninian reconstruction the basilica almost reached its final form. The last important addition happened during the pontificate of Innocent XI. His Secretary of State, Cardinal Alderano Cybo demolished the old family chapel (the second on the right) and built the sumptuous Baroque Cybo Chapel on its place that was designed by Carlo Fontana between 1682 and 1687. The large domed chapel was decorated with paintings by Carlo Maratta, Daniel Seiter and Luigi Garzi. It is regarded one of the most significant sacral monuments erected in Rome in the last quarter of the 17th century.

Later developments

During the reign of Pope Clement XI the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo was the scene of a joyful ceremony. On 8 September 1716 the pope blessed a four feet long sword, adorned with the papal arms, that he sent as a gift to Prince Eugene of Savoy, the commander of the imperial army after the prince won the Battle of Petrovaradin against the Ottomans in the Austro–Turkish War.

The most visible 18th century addition to the basilica is the spectacular funeral monument for Princess Maria Flaminia Odescalchi Chigi, the young wife of Don Sigismondo Chigi Albani della Rovere. It was designed by Paolo Posi in 1772 and sometimes dubbed the "last Baroque tomb in Rome". By the time the church was full of valuable tombs and artworks, and there was not much room left for the 19th century. Nonetheles there were smaller interventions: the Cybo-Soderini Chapel was restored in 1825, the Feoli Chapel was completely redesigned in Neo-Renaissance style in 1857 and the monumental Art Nouveau tomb of Agostino Chigi by Adolfo Apolloni was erected in 1915. After that only repairs and restorations happened regularly.

The urban setting of the basilica changed fundamentally between 1816 and 1824 when Giuseppe Valadier created the monumental Neo-Classical ensemble of Piazza del Popolo, commissioned by Pope Pius VII. The ancient monastery of the Augustinians was demolished, the extensive gardens were appropriated and a new monastery was erected on a much smaller footprint in Neo-Classical style. This building covered the whole right side of the basilica with its side chapels, wrapping around the base of the bell tower and reducing the visual prominence of the basilica on the square.

Exterior

Façade

The façade was built in early Renaissance style in the 1470s when the medieval church was rebuilt by Pope Sixtus IV. It was later reworked by Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the 17th century but pictorial sources preserved its original form, for example a woodcut in Girolamo Franzini's guide in 1588,[26] and a veduta by Giovanni Maggi in 1625.[27] The alterations included the addition of gables at the sides on the upper level, pediments above the side entrances, and the decoration of the high pediment with torch finials and stylized mountains. Originally there were tracery panels in the windows and spokes in the central rose window, and the building was free-standing with a clear view of the bell tower and the row of identical side chapels on the right.

The architecture is often attributed to Andrea Bregno but without definitive evidence. According to Ulrich Fürst the architect aimed at perfect proportioning and also at masterful restraint in the detail. "In this way he succeeded in designing the best church façade in early-Renaissance Rome."[28]

The façade was built of bright Roman travertine, and it is of two storeys high. The three entrances are accessed by a flight of stairs giving a feel of monumentality. The architecture is simple and dignified with four shallow pilasters on the lower level and two pilasters flanking the upper part with the rose window. The pilasters have irregular Corinthian capitals with ovolo moulding and floral decoration on the lower level while those on the upper story feature more simple capitals with acanthus leaves and palmettes. The side doors are surmounted by triangular pediments and their lintels have dedicatory inscriptions referring to Pope Sixtus IV. There is a pair of large arched windows above them. The main door is larger that the other two. In the middle of the pediment there is a relief of the Madonna and the child set in a shell, surrounded by cherubs. The lintel is decorated with foliage and putti who are holding torches and oak leaves. The coat-of-arms of Pope Sixtus IV is placed above the door, it is encircled by oak branches.

Bernini added the two halves of a broken segmental pediment on the sides of the upper level, replacing the original volutes, and the curved connecting element with the rich garlands. Another Baroque addition is the two flaming torches on the top and the six mountains, the family symbols of the Chigi dynasty. In the pediment there are only truncated remains of the original coat of arms.

Inscriptions

There are two lengthy inscriptions on the two sides of the main entrance quoting the bulls of Pope Sixtus IV in regard to the church. The first one, dated on 7 September 1472, begins with the words Ineffabilia Gloriosae Virginis Dei Genitricis, he granted plenary indulgence and remission of all sins to the faithful of both sexes who, truly repented and confessed, attend this church on the days of the Immaculate Conception, Nativity, Annunciation, Visitation, Purification, and Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The second one, dated on 12 October 1472, begins with the words A Sede Apostolica sunt illa benigno favore concedenda, in which he confirmed the perpetual plenary indulgence that can be earned on the earlier indicated feastdays of the Virgin, and more, commemorating the indulgences granted to the church by the former popes.

The inscriptions are famous examples of the so-called 'Sistine' style of all'antica capital lettering, a revived form of ancient Roman monumental inscriptional writing adapted to create a uniquely Renaissance idiom. The main source of this style was Bregno himself who used it on the inscriptions on his tombs.[29]

The dome

The dome of Santa Maria del Popolo was the first octagonal Renaissance dome above a rectangular crossing erected on a high tambour. At the time of its building in 1474-75 it had no real precedent, the only comparable examples are the drawings of Filarete for the utopist city of Sforzinda which were never carried out. As such the dome was a visual anomaly in the skyline of Rome but later became a prototype that has many followers in the city and in other Italian towns. The raison d'être of this novelty was the miraculous icon of Madonna del Popolo that was placed right in the center of the domed sanctuary.

The dome itself is a rather irregular mixed masonry construction of tuff blocks, bricks and mortar, covered with lead sheets. There is a thin inner shell made of bricks which can be a later addition to create a suitable surface for the frescoes. The dome is capped with an elegant globe and cross finial. The high brick tambour is punctuated with eight arched windows which originally had stone mullions like all the other openings of the church. The whole structure rests on a low square base.[30]

Bell tower

The 15th-century bell tower is placed at the end of the right transept. The structure was later incorporated into the monastery that covers the larger part of its body. The tall, rectangular brick tower was built in Northern Italian style which was unusual at the time in Rome but probably suited the taste of the Lombard congregation. The conical spire is surrounded on the corners with four cylindrical pinnacles with conical caps. Only damaged traces of the original stone mullions survived in the arched windows.

Interior

Counterfaçade

The decoration of the counterfaçade was part of the Berninian reconstruction of the church in the 17th century. The architecture is simple with a marble frame around the monumental door, a dentilled cornice, a segmental arched pediment and a dedicatory inscription commemorating the thorough rebuilding of the ancient church that Pope Alexander VII initiated as Fabio Chigi, Cardinal Priest of the basilica, and its consecration in 1655 as newly elected Pope:

ALEXANDER · VII · P · M / FABII · CHISII · OLIM · CARD / TITULARI · AEDE · ORNATA / SUI · PONTIF · PRIMORDIA / ANTIQAE · PIETATI / IN · BEATAM · VIRGINEM / CONSECR ·A · D · MDCLV.

The rose window is supported by two stucco angels sculpted by Ercole Ferrata in 1655-58 under the guidance of Bernini. The one on the left holds a wreath in her hand. On the lower part of the counterfaçade there are various funeral monuments.

Nave

The church of Santa Maria del Popolo is a Renaissance basilica with a nave and two aisles, and a transept with a central dome. The nave and the aisles have four bays, and they are covered with cross-vaults. There are four piers on each side that support the arches separating the nave from the aisles. Each pillar has four travertine semi-columns, three of them supporting the arches and the aisles vaulting while the taller fourth supports the nave vaults. The semi-columns have Composite capitals with a palmette ornament between the volutes.

The original 15th-century archtecture was largely preserved by Bernini who only added a strong stone cornice and embellished the arches with pairs of white stucco statues portraying female saints. The first two pairs on the left and the right are medieval monastic founders and reformers, the rest are all early Christian saints and martyrs. Their names are written on the spandrels of the arches with gilt letters. The cross-vaults remained undecorated and simply whitewashed. The keystones in the nave and the transept are decorated with coats of arms of Pope Sixtus IV. The Della Rovere papal escutcheons were also placed on the cornice of the intrados in the first and the last arches of the nave. These stone carvings are gilt and painted. The nave is lit by two rows of large segmental arched clerestory windows with a simple Baroque stone molding and bracketed cornice. Before the Berninian rebuilding the clerestory windows were the same mullioned arched openings like those on the facade and the bell tower.

The nave ends with a higher arch that is decorated with a sumptuous stucco group which was created during the Berninian reconstruction. The papal coat of arms of Alexander VII is seen in the middle flanked by two angel-like Victories holding palm branches who repose on rich garlands of flowers. This group is the work of Antonio Raggi.

Pairs of saints in the nave

Originally Bernini planned to fill the spaces between the windows and the arches with statues of kneeling angels. These figures appear in several drawings of a sketchbook from his workshop but by 1655 Bernini changed his mind and placed statues of female saints on the cornices. These saintly virgins are leading the eye toward the image of the Virgin on the main altar. The statues were probably designed by Bernini himself, and a supposedly autograph drawing for the figure of Saint Ursula survived in the collection of the Museum der bildenden Künste in Leipzig, but his plans were executed by the sculptors of his workshop between August and December of 1655. Their different styles could be felt within the unified scheme.[31][32]

Left side:

1st arch

- Saint Clare with a monstrance

- Saint Scholastica with a book and a dove

Nuns and founders of great female monastic orders - Sculptor: Ercole Ferrata

2nd arch

- Saint Catherine with a palm branch and the shattered wheel

- Saint Barbara with a palm branch and a tower

Early Christian martyrs in the age of persecution - Sculptor: Antonio Raggi

3rd arch

- Saint Dorothy with an angel holding garden fruits

- Saint Agatha with an angel and palm branch

Early Christian virgins and martyrs - Sculptor: Giuseppe Perone

4th arch

- Saint Tecla with a lion

- Saint Apollonia with a lamb (?)

Early Christian martyrs who suffered to keep their virginity - Sculptor: Antonio Raggi

Right side:

1st arch

- Saint Catherine of Siena with a crucifix

- Saint Teresa of Ávila with a pierced heart

Nuns and religious reformers - Sculptor: Giovanni Francesco de Rossi

2nd arch

- Saint Praxedes with sponge and vessel

- Saint Pudentiana with cloth and vessel

Ancient Roman sisters who helped the persecuted Christians - Sculptors: Paolo Naldini and Lazzaro Morelli

3rd arch

- Saint Cecilia with an organ and angel

- Saint Ursula with a banner

Early Christian virgins and martyrs - Sculptor: Giovanni Antonio Mari

4th arch

- Saint Agnes with a lamb and palm branch

- Saint Martina with a lion and palm branch

Early Christian virgins and martyrs - Sculptor: Giovanni Francesco de Rossi

Apse

The apse was designed by Donato Bramante. The oldest stained glass window in Rome can be found here, made by French artist Guillaume de Marcillat. Pinturicchio decorated the vault with frescoes, including the Coronation of the Virgin. The tombs of Cardinals Ascanio Sforza and Girolamo Basso della Rovere, both made by Andrea Sansovino, can also be found in the apse.

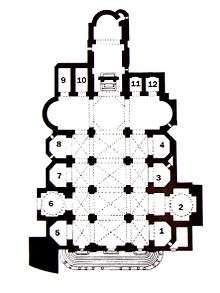

Side chapels

1. Della Rovere Chapel

The Della Rovere (or Nativity) Chapel is the first side chapel on the right aisle. It was furnished by Cardinal Domenico della Rovere from 1477 after the reconstruction of the church by his relative, Pope Sixtus IV. The pictorial decoration is attributed to Pinturicchio and his school. The main altar-piece, The Adoration of the Child with St Jerome is an exquisite autograph work by Pinturicchio himself. The tomb of Cardinal Cristoforo della Rovere (died in 1478), a work by Andrea Bregno and Mino da Fiesole, was erected by his brother. On the right side the funeral monument of Giovanni de Castro (died 1506) is attributed to Francesco da Sangallo. The chapel is one of the best preserved monuments of quattrocento art in Rome.

2. Cybo Chapel

The Cybo Chapel was radically rebuilt by Cardinal Alderano Cybo (1613-1700) between 1682 and 1687 according to the plans of Carlo Fontana. For the beauty of its paintings, the preciousness of marble revetments covering its walls and the importance of the artists involved in its construction the chapel is regarded one of the most significant sacral monuments erected in Rome in the last quarter of the 17th century.

3. Basso Della Rovere Chapel

The Basso Della Rovere Chapel was furnished by Girolamo Basso della Rovere in the 1480s. The architecture is similar to the Chapel of the Nativity and the painted decoration is attributed to Pinturicchio and his workshop. The highlights of the chapel are the great fresco of the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Augustine, Francis, Anthony of Padua and a Holy Monk above the altar, the Assumption of the Virgin Mary on the first wall and the illusionistic monochrome decoration of the pedestal with painted benches and martyrdom scenes. The original maiolica floor tiles from Deruta also survived.

4. Costa Chapel

The Costa Chapel follows the same plan as the Della Rovere chapels but it was furnished by Portuguese Cardinal Jorge da Costa who purchased it in 1488. The most important works of art are the paintings of the lunettes by the school of Pinturicchio depicting the four Fathers of the Church; the marble altar-piece by Gian Cristoforo Romano (c. 1505); and the funeral monument of Cardinal Costa by the school of Andrea Bregno. The bronze and marble funeral monument of Pietro Foscari from 1480 is preserved here.

5. Montemirabile Chapel

The chapel was named after Bishop Giovanni Montemirabile (†1479) and it was transformed into the baptistery of the basilica in 1561. The most valuable works of art in the chapel are the edicules of the baptismal font and the holy oil. They were assembled from the 15th-century fragments of demolished monuments of the church in 1657. The funeral monument of Cardinal Antoniotto Pallavicini on the left wall was also made by the Bregno workshop in 1507.

6. Chigi Chapel

Banker Agostino Chigi commissioned Raphael to design and decorate a funerary chapel for him around 1512-14. The chapel is a treasure trove of Italian Renaissance and Baroque art and is considered among the most important monuments in the basilica. The dome of the centralized octagonal chapel is decorated with Raphael's mosaics, the Creation of the World. The statues of Jonah and Elijah were carved by Lorenzetto. The chapel was later completed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini for Fabio Chigi. His additions include the sculptures of Habakkuk and the Angel and Daniel and the Lion.

7. Mellini Chapel

The chapel, which was dedicated to Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, is one of the original 15th-century hexagonal side chapels of the basilica, but its inner decoration was changed during the later centuries. It has been the funerary chapel of the Mellini family for centuries and contains several funeral monuments among them the works of Alessandro Algardi and Pierre-Étienne Monnot. The frescos of the vault were created by Giovanni da San Giovanni in 1623–24.

8. Cybo-Soderini Chapel

The Chapel of the Crucifixion or the Cybo-Soderini Chapel was remodelled in the Baroque era when a Flemish artist, Pieter van Lint executed its cycle of frescos on the vault and the lunettes which depict Angels with the Symbols of the Passion and Prophets. Two big frescos on the side walls show scenes from The Legend of the True Cross. There is a 15th-century wooden crucifix above the main altar in a Corinthian aedicule. The chapel was restored by Lorenzo Soderini in 1825.

9. Theodoli Chapel

The chapel is a hidden gem of Roman Mannerism and a major work painter and stuccoist Giulio Mazzoni. It was also called Cappella Santa Caterina «del Calice» or «del Cadice» after the classicising marble statue of Saint Catherine on the altar, the stucco chalices on the spandrels and the title of its patron, Girolamo Theodoli, Bishop of Cádiz. The decoration was originally commissioned by the first owner, Traiano Alicorni in 1555, the work was restarted under a new patron, Girolamo Theodoli in 1569 and finished around 1575.

10. Cerasi Chapel

The Cerasi Chapel holds two famous canvases painted by Caravaggio - Crucifixion of St. Peter and Conversion on the Way to Damascus (1600–01). These are probably the most important works of art in the basilica. Situated between the two works of Caravaggio is the altarpiece Assumption of the Virgin by Annibale Carracci.

11-12. Feoli and Cicada Chapels

The two identical chapels opening in the right transept are relatively insignificant in terms of artistic value in comparison with the other side chapels of the church. Both were built during Bernini's intervention in the 17th century but their present decoration is much later. The most significant work of art is the fragmented sepulchral monument of Odoardo Cicada, the Bishop of Sagona by Guglielmo della Porta which is dated around 1545. The tomb, which was originally bigger and more ornate, is located in the Cicada (or Saint Rita) Chapel.

Monuments

The church was a favourite burial place for the Roman aristocracy, clergy and literati, especially after Bernini's intervention. Besides the tombs in the side chapels the most notable monuments are:

1. Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi

The first monument as you enter the basilica is the wall tomb of Maria Eleonora I Boncompagni, the sovereign Princess of Piombino right by the door on the counterfaçade. The princess died in 1745 after visiting a hospital. Her tomb was designed by Domenico Gregorini in 1749.[33]

The funeral monument is a typical Late Baroque artwork with distinctly macabre details. On the base there is a winged dragon, the symbol of the Boncompagni family. The plaque of the epitaph is made of polished, colored stones in pietre dure. The inscription is surmounted by the personification of Time (a winged skull), the coat-of-arms of the Principality of Piombino and two allegorical figures (Charity and Meekness). The plaque is set in a white marble frame with a conch in the lower part and a gable at the top with a shell, two flaming torches and another winged skull.

2. Giovanni Battista Gisleni

The tomb of Giovanni Battista Gisleni, an Italian Baroque architect and stage designer who worked for the Polish royal court during the years 1630-1668, is probably the most macabre funeral monument in the basilica. It is set between a wooden booth and a stone half-column on the right side of the counterfaçade. The memorial was designed and installed by the architect himself in 1670 two years before his death.

The upper part of the monument is a stone plaque with a long inscription and the portrait of the deceased in a tondo which was painted by a Flemish portraitist, Jacob Ferdinand Voet. There is a painted canopy supported by angels on the wall. The lower part is more interesting: a skeleton is peeping through a window behind an iron grill. The sinister, shrouded figure is facing towards the viewer with his bony hands clutched on his breast. The stone frame of the window is decorated with a coat-of-arms and two bronze medallions. The left one shows a tree with its branches cut but sprouting new shoots and containing a caterpillar spinning its cocoon, while the right one shows the metamorphosis of the caterpillar into a moth. These are the symbols of death and resurrection. The inscriptions convey the same message: In nidulo meo moriar ("in my nest I die" i.e. in the city of Rome) and Ut phoenix multiplicabo dies ("as a phoenix I multiply my days"). There are two enigmatic inscriptions on the upper and lower part of the monument: Neque hic vivus and Neque illic mortuus ("Neither living here, nor dead there").

On this tomb the skeleton is not the personification of Death as in other Baroque tombs but a representation of the deceased (the transi image) on his way towards the resurrection and due to this "death became a symbol for life".[34]

3. Maria Flaminia Odescalchi Chigi

The funeral monument of Princess Maria Flaminia Odescalchi Chigi is sometimes dubbed the "last Baroque tomb in Rome".[35] It is probably the most visually stunning, exuberant and theatrical sepulchral monument in the basilica. It was built in 1772 for the young princess, the first wife of Don Sigismondo Chigi Albani della Rovere, the 4th Prince of Farnese, who died in childbirth at the age of 20. It was designed by Paolo Posi, a Baroque architect who was famous for his ephemeral architecture built for celebrations, and executed by Agostino Penna. The tomb is located by the pillar between the Chigi and Montemirabile Chapels.

The monument shows the influence of Bernini's tomb for Maria Raggi in Santa Maria sopra Minerva. Posi used the heraldic symbols of the Chigi and the Odescalchi to celebrate the intertwining of the two princely families. In the lower part of the monument a white marble Odescalchi lion is climbing a mountain of the Chigi; to the right a smoking incense burner alludes to the Odescalchis again. A gnarled bronze oak tree (Chigi) grows from the mountain with a huge red marble robe on its branches. The robe is hemmed with gold and decorated with an epitaph made of golden letters and also the stars of the Chigi and the incense burners of the Odescalchi at the lower part. In the upper part of the tomb a white marble eagle and two angels are carrying the black and white marble portrait of dead which is set in a richly decorated golden medaillon.

In the 19th century the monument was dismissed as tawdry. Stendhal called it an "outburst of the execrable taste of the 18th century" in his 1827 Promenades dans Rome.[36]

4. Giovanni Gerolamo Albani

One of most important Mannerist funeral monuments in the basilica is the tomb of Cardinal Gian Girolamo Albani, an influential politician, jurist, scholar and diplomat in the papal court in the last decades of the 16th century. He died in 1591. The Late Renaissance monument is one of the main works of the Roman sculptor, Giovanni Antonio Paracca. The bust of the Cardinal is a realistic portrait of the old statesman. He is seen praying with his head turned toward the main altar. Facing this monument the cenotaph of Cardinal Giovanni Battista Pallavicino (1596) is likewise attributed to Paracca.

5. Ludovico Podocataro

The wall tomb of the Cypriot Cardinal Ludovico Podocataro, secretary and physician of Pope Alexander VI, is a monumental work of Roman Renaissance sculpture. The prominent humanist and papal diplomat was buried on 7 October 1504 with great pomp; the location of the tomb in the right transept was originally close to the funerary chapel of the Borgia family, Podocataro's patrons, but the chapel is no longer extant.

Originally the monument had a dual function as an altar and tomb. It was probably commissioned by the cardinal between 1497, when he made a donation to the Augustinian church and 1504, his death. The master(s) of the monument are unknown but on stylistic grounds it is assumed to be the work of different groups of sculptors. The architectural composition is traditional and somewhat conservative for the beginning of the 16th century, it follows the models set by Andrea Bregno.

6. Bernardino Lonati

The wall tomb of Cardinal Bernardino Lonati is similar to the coeval sepulchre of Ludovico Podocataro, and they both belong to the group of monuments from the age of Pope Alexander VI which made the basilica the shrine of the Borgia dynasty at the beginning of the 16th century. The monument was financed by Cardinal Ascanio Sforza after the death of his protégée on 7 August 1497, not long after Lonati had led an unsuccessful expedition against the Orsini family by order of the Pope. The architectural composition of the monument follows the models set by Andrea Bregno.

Cardinal Priests

- Tolomeo Gallio (20 April 1587 - 2 Dec 1587)

- Scipione Gonzaga (15 Jan 1588 - 11 Jan 1593)

- Ottavio Acquaviva d'Aragona (15 March 1593 - 22 Apr 1602)

- Francesco Mantica (17 Jun 1602 - 28 Jan 1614)

- Filippo Filonardi (9 Jul 1614 - 29 Sept 1622)

- Guido Bentivoglio (26 Oct 1622 - 7 May 1635)

- Lelio Biscia (9 Febr 1637 - 19 Nov 1638)

- Lelio Falconieri (31 Aug 1643 - 14 Dec 1648)

- Mario Theodoli (28 Jan 1649 - 27 Jun 1650)

- Fabio Chigi (12 Mar 1652 - 7 Apr 1655), later Pope Alexander VII

- Gian Giacomo Teodoro Trivulzio (14 May 1655 - 3 Aug 1656)

- Flavio Chigi (23 Apr 1657 - 18 Mar 1686)

- Savio Mellini (12 Aug 1686 - 12 Dec 1689)

- Francesco del Giudice (10 Apr 1690 - 30 Mar 1700)

- Andrea Santacroce (30 Mar 1700 - 10 May 1712)

- Agostino Cusani (30 Jan 1713 - 27 Dec 1730)

- Camillo Cybo (8 Jan 1731 - 20 Dec 1741)

- Francesco Ricci (23 Sept 1743 - 8 Jan 1755)

- Franz Konrad von Rodt (2 Aug 1758 - 16 Oct 1775)

- Giovanni Carlo Bandi (18 Dec 1775 - 23 March 1784)

- Giovanni Maria Riminaldi (11 Apr 1785 - 29 Jan 1789)

- Francesco Maria Pignatelli (21 Febr 1794 - 2 Apr 1800)

- Ferdinando Maria Saluzzo (20 Jul 1801 - 28 May 1804)

- Francesco Cesarei Leoni (1 Oct 1817 - 25 Jul 1830)

- Francisco Javier de Cienfuegos y Jovellanos (28 Febr 1831 - 21 Jun 1847)

- Jacques-Marie Antoine Célestin Dupont (4 Oct 1847 - 26 May 1859)

- Carlo Sacconi (30 Sept 1861 - 8 Oct 1870)

- Flavio Chigi (15 Jun 1874 - 15 Febr 1885)

- Alfonso Capecelatro di Castelpagano (15 Jan 1886 - 14 Nov 1912)

- José Cos y Macho (2 Dec 1912 - 17 Dec 1919)

- Juan Soldevilla y Romero (15 Dec 1919 - 4 Jun 1923)

- George William Mundelein (27 Marc 1924 - 2 Oct 1939)

- James Charles McGuigan (18 Febr 1946 - 8 Apr 1974)

- Hyacinthe Thiandoum (24 May 1976 - 18 May 2004)

- Stanislaw Dziwisz (24 March 2006 – present)

References

- ↑ Ambrogio Landucci, cited by Alessandro Locchi: La vicenda della sepoltura di Nerone. in: Fabrizio Vistoli (ed.): Tomba di Nerone. Toponimo, comprensorio e zona urbanistica di Roma Capitale, Rome, Edizioni Nuova Cultura, 2012, pp. 111-112

- ↑ Iacobo de Albericis (Giacomo Alberici): Historiarum sanctissimae et gloriosissimae virginis deiparae de populo almae urbis compendium, Roma, Nicolai Mutij (Nicolo Muzi), 1599, pp. 1-10.

- ↑ Ambrogio Landucci:Origine del tempio dedicato in Roma alla Vergine Madre di Dio Maria, presso alla Porta Flaminia, detto hoggi del popolo, Roma, Franceso Moneta, 1646, pp. 7-20.

- ↑ Ottavio Panciroli: Tesori nascosti dell'alma citta' di Roma, Rome, Heredi di Alessandro Zannetti, 1625, p. 449

- ↑ Santa Maria del Popolo a Roma, ed. E. Bentivoglio and S. Valtieri, Bari-Roma, 1976, p. 203.

- ↑ Nikolaus Muffel: Beschreibung der Stadt Rom, herausg. Wilhelm Vogt, Literarischer Verein, Stuttgart, 1876, p. 53

- ↑ The Pilgrimage of Arnold Von Harff (ed. and trans. Malcolm Letts), London, The Hakluyt Society, 1946, pp. 34-35

- ↑ Platner & Ashby: “Sepulcrum Domitiorum”, in Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, London, 1929, p. 479

- ↑ Kai-Michael Sprenger: The Tiara in the Tiber. An Essay on the damnatio in memoria of Clement III (1084-1100) and Rome’s River as a Place of Oblivion and Memory, Reti Medievali Rivista, 13, 1 (2012), pp. 164-168

- ↑ Mariano Armellini: Le chiese di Roma dal secolo IV al XIX, Tipografia Vaticana, 1891, p. 320

- ↑ Landucci, pp. 76-77

- ↑ Paul Fabre: Un nouveau catalogue des Églises de Rome, Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire, 1887, Vol. 7, p. 437

- ↑ Anne Dunlop: Pinturicchio and the Pilgrims: Devotion and the Past at Santa Maria Del Popolo, Papers of the British School at Rome, 2003, p. 267, citing Oliger: 'De fratribus minoribus apud S. Mariae Populi Romae a. 1250 habitantibus', Archivum Franciscanum Historicum, 18 (1925)

- ↑ Francis Roth: Il Cardinale Riccardo degli Annibaldi, primo protettore dell'ordine agostiniano, in: Augustiniana vol. 2-3 (1952-53)

- ↑ The inscription was already recorded by Fioravante Martinelli: Roma ricercata, 1658, p. 302

- ↑ Katherine Walsh: The Obsevance: Sources for a History of the Observant Reform Movement in the Order of Augustinian Friars in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, in: Rivista di storia della chiesa in Italia XXXI, 1977, Herder, Rome, pp. 59, 62, 64-65

- ↑ Jill E. Blondin: Power Made Visible: Pope Sixtus IV as "Urbis Restaurator" in Quattrocento Rome, The Catholic Historical Review Vol. 91, No. 1, pp. 1-25

- ↑ Piero Tomei: L'architettura a Roma nel Quattrocento, Roma, Casa Editrice Fratelli Palombi, 1942, p. 148

- ↑ Landucci, pp. 22-23

- ↑ Lisa Passaglia Bauman: Piety and Public Consumption: Domenico, Girolamo, and Julius II della Rovere at Santa Maria del Popolo, in: Patronage and Dynasty: The Rise of the Della Rovere in Renaissance Italy, ed. Ian F. Verstegen, Truman State University Press, 2007, p. 40

- ↑ Loren Partridge and Randolph Starn: A Renaissance Likeness: Art and Culture in Raphael's Julius II, University of California Press, 1980, p. 96

- ↑ Hans Schneider: Martin Luthers Reise nach Rom – neu datiert und neu gedeutet. In: Werner Lehfeldt (Hrsg.): Studien zur Wissenschafts- und zur Religionsgeschichte, De Gruyter, Berlin/New York 2011

- ↑ Heinz Schilling: Martin Luther: Rebel in an Age of Upheaval, transl. Rona Johnston, Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 81

- ↑ http://www.vicariatusurbis.org/?page_id=188&ID=8

- ↑ Volker Reinhardt: Der unheimliche Papst: Alexander VI. Borgia 1431-1503, Verlag C.H. Beck, 2007, p. 53

- ↑ Le cose maravigliose dell'alma citta di Roma anfiteatro del mondo, Gio. Antonio Franzini herede di Girolamo Franzini, 1600, Roma, p. 27

- ↑ Aloisio Antinori: La magnificenza e l'utile: Progetto urbano e monarchia papale nella Roma del Seicento, Gangemi Editore, 2008, pp. 108-109

- ↑ Stefan Grundmann, Ulrich Fürst: The Architecture of Rome: An Architectural History in 400 Individual Presentations, Axel Menges, 1998 p. 105

- ↑ David Boffa: Artistic Identity Set In Stone: Italian Sculptors' Signatures c. 1250-1550, 2011, pp. 87-88

- ↑ Federico Bellini: La cupola nel Quattrocento, in: Santa Maria del Popolo. Storia e restauri, ed. Ilaria Miarelli Mariani, Maria Richiello, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 2009, pp. 368-381

- ↑ Jennifer Montagu: Bernini Sculptures Not by Bernini, in: Irving Lavin (ed.): Gianlorenzo Bernini: New Aspects of His Art and Thought, The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park and London, 1985, pp. 28-29

- ↑ Jacob Bean: 17th Century Italian Drawings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979, p. 43

- ↑ Claudio De Dominicis: Carlo De Dominicis, architetto del Settecento romano (Roma, 2006) p. 74

- ↑ Kathleen Cohen: Metamorphosis of a Death Symbol: The Transi Tombs in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance (University of California Press, Berkeley-Los Angeles-London) p. 185

- ↑ http://romeartlover.tripod.com/Popolo.html

- ↑ Stendhal: Promenade dans Rome, Vol. 1 (Editions Jérôme Millon, 1993), p. 120

Books

- Raffaele Colantuoni, La chiesa di S. Maria del Popolo negli otto secoli dalla prima sua fondazione, 1099-1899: storia e arte (Roma: Desclée, Lefebvre, 1899).

- John K. G. Shearman, The Chigi Chapel in S. Maria Del Popolo (London: Warburg Institute, 1961).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santa Maria del Popolo (Rome). |

- SM del Popolo: A Multimedia Presentation of the church and its setting, Australian National University

- Santa Maria del Popolo Video Introduction

- Santa Maria del Popolo, article and photos at Sacred Destinations

- Piazza del Popolo, at "Rome Art Lover"