Sanford Robinson Gifford

| Sanford Robinson Gifford | |

|---|---|

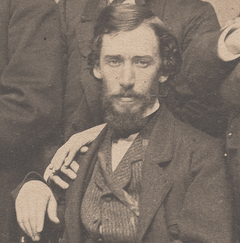

Gifford in 1861 as a Union Army soldier | |

| Born |

July 10, 1823 Greenfield, New York |

| Died |

August 29, 1880 (aged 57) New York City |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Landscape art, Painting |

| Movement | Luminism |

Sanford Robinson Gifford (July 10, 1823 – August 29, 1880) was an American landscape painter and one of the leading members of the Hudson River School. Gifford's landscapes are known for their emphasis on light and soft atmospheric effects, and he is regarded as a practitioner of Luminism, an offshoot style of the Hudson River School.

Not to be confused with artist Robert Swain Gifford (1840–1905), no apparent relation.[1]

Childhood and early career

Gifford was born in Greenfield, New York[2] and spent his childhood in Hudson, New York, the son of an iron foundry owner. He attended Brown University 1842-44, where he joined Delta Phi, before leaving to study art in New York City in 1845. He studied drawing, perspective and anatomy under the direction of the British watercolorist and drawing-master, John Rubens Smith.[3] He also studied the human figure in anatomy classes at the Crosby Street Medical college and took drawing classes at the National Academy of Design.[2] By 1847 he was sufficiently skilled at painting to exhibit his first landscape at the National Academy and was elected an associate in 1851, an academician in 1854. Thereafter Gifford devoted himself to landscape painting, becoming one of the finest artists of the early Hudson River School.

Gifford's travels

Like most Hudson River School artists, Gifford traveled extensively to find scenic landscapes to sketch and paint. In addition to exploring New England, upstate New York and New Jersey, Gifford made extensive trips abroad. He first traveled to Europe from 1855 to 1857, to study European art and sketch subjects for future paintings. During this trip Gifford also met and traveled extensively with Albert Bierstadt and Worthington Whittredge.

In 1858, he traveled to Vermont, "apparently" with his friend and fellow painter Jerome Thompson. Details of their visit were carried in the contemporary Home Journal. Both artists submitted paintings of Mount Mansfield, Vermont's tallest peak, to the National Academy of Design's annual show in 1859. (See "Mt. Mansfield paintings controversy" below.) 'Thompson's work, "Belated Party on Mansfield Mountain," is now owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York,' according to the report.[4]

Thereafter, he served in the Union Army as a corporal in the 7th Regiment of the New York Militia upon the outbreak of the Civil War. A few of his canvases belonging to New York City's Seventh Regiment and the Union League Club of New York[5] are testament to that troubled time.

During the summer of 1867, Gifford spent most of his time painting on the New Jersey coast, specifically at Sandy Hook and Long Branch, according to an auction Web site. "The Mouth of the Shrewsbury River," one noted canvas from the period, is a dramatic scene depicting a series of telegraph poles extending into an atmospheric distance underneath ominous storm clouds.[6]

Another journey, this time with Jervis McEntee and his wife, took him across Europe in 1868. Leaving the McEntees behind, Gifford traveled to the Middle East, including Egypt in 1869. Then in the summer of 1870 Gifford ventured to the Rocky Mountains in the western United States, this time with Worthington Whittredge and John Frederick Kensett. At least part of the 1870 travels were as part of a Hayden Expedition, led by Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden.[7]

In the studio

Returning to his studio in New York City, Gifford painted numerous major landscapes from scenes he recorded on his travels. Gifford's method of creating a work of art was similar to other Hudson River School artists. He would first sketch rough, small works in oil paint from his sketchbook pencil drawings. Those scenes he most favored he then developed into small, finished paintings, then into larger, finished paintings.[8]

"Chief pictures"

Gifford referred to the best of his landscapes as his "chief pictures". Many of his chief pictures are characterized by a hazy atmosphere with soft, suffuse sunlight. Gifford often painted a large body of water in the foreground or middle distance, in which the distant landscape would be gently reflected. Examples of Gifford's "chief pictures" in museum collections today include:

- Lake Nemi (1856–57), Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio

- The Wilderness (1861), Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio

- A Passing Storm (1866), Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut

- Ruins of the Parthenon (1880), Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Gifford's death

On August 29, 1880, Gifford died in New York City, having been diagnosed with malarial fever. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City celebrated his life that autumn with a memorial exhibition of 160 paintings. A catalog of his work published shortly after his death recorded in excess of 700 paintings during his career.

Between 1955 and 1973, Gifford's heirs donated the artist's collection of letters and personal papers to the Archives of American Art, a research center which is part of the Smithsonian Institution. In 2007, these papers were digitally scanned in their entirety and made available to researchers as the Sanford Robinson Gifford Papers Online.[9]

Mt. Mansfield paintings/controversy

Gifford painted some 20 paintings from the sketches he did while in Vermont in 1858. (See "travels" section above.) Of these, "Mount Mansfield, 1858" was the National Academy submission in 1859, and another painted in 1859, "Mount Mansfield, Vermont," came in 2008 to be in the center of a controversy over its deaccession by the National Academy in New York.[4] The controversy had been reported in December, saying that the sale of paintings to cover operating expenses was against the policy of the Association of Art Museum Directors, which organization in turn was asking its members to "cease lending artworks to the academy and collaborating with it on exhibitions." The report also said the 1859 painting in question was "donated to the academy in 1865 by another painter, James Augustus Suydam."[10] Amongst much more detail about on the deaccession, a later Times report said that the National Academy had sold works by Thomas Eakins and Richard Caton Woodville in the 1970s and 1990s respectively, according to David Dearinger, a former curator. "When the academy later applied to the museum association for accreditation, Mr. Dearinger recalled, it was asked about the Woodville sale and promised not to repeat such a move," the Times reported.[11] News of the sale was originally broken, as reported in the Times, by arts blogger Lee Rosenbaum.[12] As cited by Rosenbaum, her original story, with additional details on other contemplated sales by the Academy, ran December 5.[13] The Times did subsequently report on the other contemplated sales, without credit to Rosenbaum.[14]

Other paintings

- "Sunday Morning at Camp Cameron" (at Meridian Hill about two miles northwest of the Capitol in Georgetown Heights)[15] (1861)

- "Bivouac of the Seventh Regiment at Arlington Heights, Virginia" (1861)

- "Camp of the Seventh Regiment, near Frederick, Maryland, in July 1863" (1864)[2]

- "Twilight in the Adirondacks" [16]

- "A Home in the Wilderness" (1866), Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio [17]

- "Evening over the Settler's Home"[18]

- A seascape (1867) borrowed back by the artist to show in the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, 1876.[19]

- A painting of Sandy Hook [20]

- "Venetian Isle of San Georgio"

- A view of Venice from the Grand Canal, with church Santa Maria della Salute[22][23]

- "Fishing Boats in the Adriatic"[24]

- "Fishing Boats entering the harbor at Brindisi"

- View of Mount Rainier on Puget Sound, Bay of Tacoma, Washington Territory

- On the lake of Geneva, near Villeneuve, with the Alps [25][26]

- "A Coming Shower over Black Mountain, Lake George" purchased by George C. Clark for $1,025 at auction following artist's death in 1880, 18"h x 34"w.

- "The Peak of the Matterhorn at Sunrise" purchased by George C. Clark for $950 at auction following artist's death in 1880, 40"h x 28"w. Photos and sketches of SRG's visit to the Matterhorn are available via the Smithsonian Web site.[27]

- "The Path to the Mountain House in the Catskills" purchased by E. H. Gordon for $505 at auction following artist's death in 1880.

- "Bivouac of the Seventh Regiment at Arlington Heights, Virginia" (1861) purchased by William Schaus for $630 at auction following artist's death in 1880. The painting had been damaged in "the Madison-Square Garden disaster when on exhibition at the Hahnemann Hospital Exhibit, but was afterward restored by the artist," it is reported.

- "Baltimore in 1862. A Sunset from Federal Hill" sold for $325 at auction following artist's death in 1880. Also damaged to some degree in the Madison-Square disaster, and presumably restored.[28]

- "Bronx River, New-York" sold for $310 at auction following artist's death in 1880.

- "On the Sea-Shore, Looking Eastward at Sunset" sold for $305 at auction following artist's death in 1880.

- "The View from South Mountain in the Catskills" sold for $300 at auction following artist's death in 1880.

- "Hook Mountain, near Nyack on the Hudson" sold for $300 at auction following artist's death in 1880.

- "Outlet of Catskill Lake" sold for $275 at auction following artist's death in 1880.

- "Cliffs at Porcupine Island, Mount Desert" sold for $230 at auction following artist's death in 1880.

- "Echo Lake, in the Franconia Mountains, New Hampshire" sold for $215 at auction following artist's death in 1880.

- "Hudson River valley from South Mountain" sold for $215 at auction following artist's death in 1880.

- "Rocks at Manchester, Mass" sold for $205 at auction following artist's death in 1880.[29]

- "Hunter Mountain,Twilight" An oil painting that opened the way to modern environmentalism and the Catskill and Adirondack Forest Preserves [30]

See also

References

- ↑ Gallery bio. Childs Gallery.

- 1 2 3 American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution. Biographical information.

- ↑ Myers, Kenneth (1987). The Catskills: Painters, Writers, and Tourists in the Mountains, 1820-1895. Hudson River Museum. ISBN 978-0-943651-05-7.

- 1 2 Scandal over Mansfield by Mark Bushnell, Rutland [Vt.] Herald, January 11, 2009. Retrieved 1/13/09.

- ↑ http://hamiltonauctiongalleries.com/Gifford-62.JPG

- ↑ "2003". Artfact.com. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ↑ SRG pictured on horseback, with caption Picture 1. Archive of American Art. Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ https://images.google.com/images?hl=en&q=sanford+gifford&ie=UTF-8&sa=N&tab=ni

- ↑ http://www.aaa.si.edu/collectionsonline/giffsanf/index.cfm

- ↑ "National Academy Sells Two Hudson River School Paintings to Bolster Its Finances" by Randy Kennedy, The New York Times, December 6, 2008, p. C1, NY edition. Retrieved 1/13/09.

- ↑ "Branded a pariah, the National Academy is struggling to survive" by Robin Pogrebin, The New York Times, December 23, 2008, p. C1, NY edition. With image of painting. Retrieved 1/13/09.

- ↑ '"Lee Rosenbaum" (not alter ego, "CultureGrrl") in NY Times Today' December 6, 2008 Culture Grrl blogpost. Retrieved 1/13/09.

- ↑ 'Auction House Privately Handled the National Academy Sales; Two More Possible Disposals Identified' December 5, 2008 Culture Grrl blogpost. Retrieved 1/13/09.

- ↑ "Branded a pariah, the National Academy is struggling to survive" by Robin Pogrebin, The New York Times, December 23, 2008, p. C1, NY edition. Retrieved 1/13/09.

- ↑ The Blue and Gray in Black and White by Bob Zeller (Praeger Publishers 2005) p. 50.

- ↑ Undated review in The Leader by George Arnold, American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Image.

- ↑ Contemporary mention of painting. jpg. American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Appletons' Journal pp.315-16 March 4, 1876. Retrieved 1-13-09.

- ↑ Noted in Independent review Ap. 23, 1868. jpg. American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ The Annual Exhibition of the National Academy 1870 p. 705. jpg. American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Contemporary review in New York Herald, Monday, June 27, 1870. jpg. American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Contemporary review 1872 (date?). jpg. American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Contemporary review of painting. jpg. American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ "A visit to the studio of Mr. Sanford R. Gifford" by J.F.W. "Evening Post" (N.Y.) March 18, 1875. "JFW" is almost certainly John Ferguson Weir.

- ↑ John Ferguson Weir: The Labor of Art by Betsy Fahlman (University of Delaware Press 1997) Reports close connection between the two artists, also both National Academy and 7th Regiment members.

- ↑ American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution Mont Cervin (Matterhorn), circa 1856-circa 1868. (Box 2 (pam), Folder 16).

- ↑ "''The New York Times'' April 23, 1880". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ↑ Clipping dated April 21, 1881, identified only as "New York." American Archives of Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Johnson, Kirk (June 7, 2001). "Hunter Mountain Paintings Spurred Recovery of Land". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

Further reading

- Avery, Kevin J., & Kelly, Frank (2003). Hudson River school visions: the landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780300101843.

- Weiss, Ila (1987). Poetic Landscape: The Art and Experience of Sanford R. Gifford. Newark, DE: Associated University Presses, Inc. ISBN 0-87413-199-5.

- Wilton, Andrew & Barringer, Tim (2002). American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States 1820-1880. Princeton: The Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09670-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sanford Robinson Gifford. |

- Gallery

- White Mountain paintings by Sanford Robinson Gifford

- Sanford Robinson Gifford papers at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- www.SanfordRobinsonGifford.org 150 works by Sanford Robinson Gifford

- Art and the empire city: New York, 1825-1861, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Gifford (see index)

- American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Gifford (see index)