San Salvador Island

| San Salvador Island Guanahani Watlings Island | ||

|---|---|---|

| Island and District | ||

|

Map of San Salvador Island | ||

| ||

San Salvador Island | ||

| Coordinates: 24°06′N 74°29′W / 24.100°N 74.483°WCoordinates: 24°06′N 74°29′W / 24.100°N 74.483°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| Island | San Salvador | |

| District | San Salvador | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 163 km2 (63 sq mi) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 930[1] | |

| Time zone | Eastern Time Zone (UTC-5) | |

| Area code(s) | 242 | |

San Salvador Island (known as Watlings Island from the 1680s until 1925) is an island and district of the Bahamas. It is widely believed that during Christopher Columbus' first expedition to the New World, San Salvador Island was the first land he sighted and visited on 12 October 1492; he named it San Salvador after Christ the Saviour.[2][3] Columbus' records indicate that the native Lucayan inhabitants of the territory, who called their island Guanahani, were "sweet and gentle".[4]

History

When he made landfall on the tiny island of San Salvador in 1492, Columbus thought he had reached the East Indies. This was precisely his quest- to find an all-water route to the orient so that European traders, who traded precious spices, could avoid paying tribute to the Middle Eastern middlemen who skimmed profits off overland trading ventures.[5] The island was called Guanahani by the Natives of the island, and the name was promptly changed following Spanish colonization. In the 17th century, San Salvador was settled by an English Buccaneer, John Watling (alternately referred to as George Watling), who gave the island its alternative historical name. The United Kingdom gained control of what are now the Bahamas in the early 18th century. In 1925 the name "San Salvador" was officially transferred from another place, now called Cat Island, and given to "Watlings Island," based on historians believing this was a more likely match for Columbus' description of Guanahani. Advocates of Watling's Island included H. Major, the map-custodian of the British Museum; and the geographer Clements R. Markham,[6] as well as the American sea historian Samuel E. Morison.

The American Fr. Chrysostom Schreiner OSB, the first Catholic priest permanently assigned to the Bahamas, served primarily at St. Francis Xavier in Nassau. A history enthusiast, he researched Columbus' landing extensively and promoted San Salvador as the correct landing site. In retirement, Fr. Chrysostom relocated to San Salvador, where he died on 3 Jan 1928. He was buried the next day. Memorial Masses were celebrated in Nassau; Collegeville, Minnesota (the site of St. John's Abbey, his monastery); and New York. Cardinal Hayes referred to him as the Catholic Apostle to the Bahamas; he was a unique religious presence on the islands. His tomb can still be seen on San Salvador.

Tourism

Today, thanks to its many sandy beaches, the island's prosperous main industry is tourism. About 940 people reside on San Salvador Island and its principal community is Cockburn Town, the seat of local government. The town has a population of 271.[7] A Club Med resort, called "Columbus Isle", is located just north of Cockburn Town.

Nearby is the Pleistocene Cockburn Town Fossil Reef.[8] Fossilized Staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis), and Elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) are present near the crest of the fossil reef, and other corals, such as Montastraea, Diploria, and Porites, are preserved.

The Gerace Research Centre (formerly the Bahamian Field Station) is located on the north end of the island on the shores of Grahams Harbour. More than 1,000 students and researchers work from the station every year as a base of operations for studying tropical marine geology, biology, and archaeology.

The island is home to many shallow-water reefs, where snorkelers can observe hundreds of fish species without the use of scuba equipment. It is also known for its quick drop in the submerged platform of the island, allowing for numerous dive sites. The western coast has many wall reefs, with steep drop offs, while the northern coast has many shallow barrier reefs, particularly surrounding Grahams Harbour, a large shallow lagoon.

The island is served by San Salvador International Airport.

The Dixon Hill lighthouse is located on the island south of Dixon Hill Settlement on the east side of the island. It is approximately 160 feet tall, and was constructed in 1887 by the Imperial Lighthouse Service.[9] Beside beaches, there are several monuments, ruins and shipwrecks in the area that are major tourist attractions.[10][11]

Hurricanes

Hurricane Lili struck San Salvador in 1996.[12] Hurricane Floyd struck in 1999, and caused damage to homes, tourist facilities, businesses, and infrastructure, and caused considerable beach erosion.[13]

On October 4, 2015 report from the Bahamas in the wake of Hurricane Joaquin indicate that several islands are, in the words of one journalist, "completely obliterated". Photojournalist Eddy Rafael observed the devastation from the air Saturday morning as part of an assessment flight that included San Island.[14]

The damage seemed to be confined to just a few specific areas. The Club Med resort on San Salvador was destroyed, Rafael reported, but the power station looked intact from the air. Club Med later stated that much of the landscaping was damaged, but no guests were present at the time of the hurricane and none of the staff were injured.[14]

Physical Oceanography

San Salvador Island sits on its own isolated carbonate platform surrounded by a narrow shelf that reaches a depth of up to 40 meters.[15][16] Past the shelf, the slope becomes almost vertical and depth quickly increases to 4,000 meters.[15][17] San Salvador Island experiences a semi-diurnal tide, with two high tides and two low tides per day.[18] Water temperature in San Salvador can range from 23⁰C to 29⁰C depending on the location and time of year. Salinity and dissolved oxygen are consistent throughout the island and throughout the year (35 ppt and 6.0% respectively).[17]

Most of San Salvador Island is surrounded by fringing reefs.[17] In many areas, such as Fernandez Bay, the shore is rocky and populated by reef urchins (Echinometra viridis). Moving away from shore, the bottom slopes gradually and may have several patch reefs surrounded by a sandy bottom. These patch reefs are home to hundreds of fish, invertebrates, and algae.[17] The depth continues to increase to about 25 meters at the farthest edge of the shelf, which can be between 400 and 1,500 meters from shore.[17]

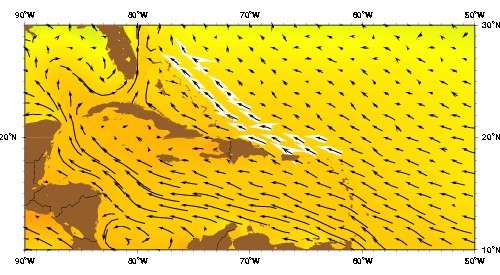

Antilles Current

Wind and wave action in San Salvador is influenced by the Antilles Current. The Antilles Current originates south of the Bahamas, Puerto Rico, and Cuba and moves northward where it merges with the Gulf Stream.[19] This current cools the waters around San Salvador in the summer and warms the water around the island in the winter. This keeps the water temperature relatively mild and consistent throughout the year.[17]

The coasts of San Salvador are very different from each other. The west coast of San Salvador faces the rest of the Bahamian islands and the Grand Bahama bank. Most of these islands are sheltered from significant winds and wave action. This is also true of San Salvador’s west coast; the water is generally calmer and visibility tends to be greater. In contrast, the eastern coast of San Salvador is windward and completely exposed to the rest of the Atlantic Ocean and is not protected by any other geological formations.[16] As a result, wave action is much stronger and visibility is lower. Evidence of currents from the Atlantic Ocean can be found on the east coast in the form of trash and debris on the beaches. During Hurricane Joaquin in October 2011, the SS El Faro cargo ship went down approximately 50 miles east of San Salvador. Several weeks later, pieces of the container that had been swept away by the current were reported on the beaches of San Salvador.[20]

Students from Jacksonville University’s Marine Science Research Institute launched a drifter buoy from a boat at the northern tip of San Salvador Island on June 27, 2016.[21] The drifter was carried north by the Antilles Current and was caught in a small ocean gyre just east of the continental shelf and north of the Abaco Islands. The drifter circled the gyre for several weeks until it was pushed westward by Hurricane Matthew in October 2016. From there the buoy continued drifting southwest toward the western edge of Grand Bahama and was then pushed northwest toward Florida. The drifter landed at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on December 23, 2016. Attempts to recover the drifter have been unsuccessful.

Government

The current Administrator is Mr. Gilbert C. Kemp.

Gallery

- View of North Point, Rice Bay, and Dixon Hill Settlement, facing north from the lighthouse in 1998.

- View of Grahams Harbour facing west from North Point in 1998. The water tower at left is located at the Gerace Research Centre, but no longer stands.

Seagrass (Thalassia testudinum) bed with several echinoids (Tripneustes ventricosus), Grahams Harbour

Seagrass (Thalassia testudinum) bed with several echinoids (Tripneustes ventricosus), Grahams Harbour Elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) on the crest of Gaulin Reef

Elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) on the crest of Gaulin Reef

References

- ↑ "PRELIMINARY POPULATION AND HOUSING COUNT BY ISLAND AND SUPERVISORY DISTRICT, ALL BAHAMAS: CENSUS 2010" (PDF). Bahamas Department of Statistics.

- ↑ William D. Phillips Jr., "Columbus, Christopher", in David Buisseret (ed.), The Oxford Companion to World Exploration, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, online edition 2012).

- ↑ In 1986 the National Geographic Society made an alternative suggestion of Samana Cay. For a brief discussion of the controversy see William D. Phillips, Jr., and Carla Rahn Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 155-5.

- ↑ Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, New York: Henry Holt, p 2.

- ↑ Nash, Gary B. Red, White and Black: The Peoples of Early North America Los Angeles 2015. Chapter 1, p. 18

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "San Salvador (1)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "San Salvador (1)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ SAN SALVADOR POPULATION BY SETTLEMENT AND TOTAL NUMBER OF OCCUPIED DWELLINGS: 2010 CENSUS - Bahamas Department of Statistics

- ↑ Curran, HA and B White. Field Guide to the Cockburn Town Fossil Coral Reef, San Salvador, Bahamas. p. 71-96., In Proceedings of the 2nd Symposium on the Geology of The Bahamas, 1984. JW Teeter (ed.).

- ↑ www.thebahamasguide.com/islands/sansalvador/default.htm "San Salvador", The Bahamas Guide, Retrieved 6 March 2001

- ↑ http://www.bahamas.com/islands/san-salvador "San Salvador", The Official site of the Bahamas, Retrieved 21 September 2013

- ↑ http://www.bahamas.com/islands/san-salvador "San Salvador", The Bahamas, Retrieved 21 September 2013

- ↑ Garver, John (January 3, 2003). "Some effects of Hurricane Lili (Oct 1996)". Union College. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ↑ Curran, H. A., Delano, P., White, B., and Barrett, M., 2001, "Coastal Effects of Hurricane Floyd on San Salvador Island, Bahamas," In Proceedings of the 10th Symposium on the Geology of The Bahamas, 2001. Greenstein, B. J., and Carney, C. K.(eds.)

- 1 2 "Hurricane Joaquin Exits Bahamas; Several Islands "Completely Obliterated"". The Weather Channel. 3 October 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- 1 2 Littler, M.M.; Littler, D.S.; Blair, S.M.; Norris, J.N. (1986). "Deep-water plant communities from an uncharted seamount off San Salvador Island, Bahamas: distribution, abundance, and primary productivity" (PDF). Deep Sea Research. 33 (7): 881–892.

- 1 2 Peckol, P.M.; Curran, A.; Greenstein, B.J.; Blair, S.M.; Norris, J.N. (2003). "Assessment of coral reefs off San Salvador Island, Bahamas(stony corals, algae and fish populations)" (PDF). Atoll Research Bulletin. 496: 124–145.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gerace, D.T.; Ostrander, G.K.; Smith, G.W. (1998). "San Salvador, Bahamas". Caribbean Coastal Marine Productivity: 229–245.

- ↑ "Tide Predictions - San Salvador TEC4631 Tidal Data Daily View - NOAA Tides & Currents". tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- ↑ Talley, L.D. (2011). Descriptive physical oceanography: an introduction. Academic press.

- ↑ "Debris piece in Bahamas matches El Faro's cargo log". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- ↑ "Jacksonville Marine Lab/ Bolles School/ Robin Paris drifters deployed in 2016". nefsc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

External links

- High resolution map of the island

- Multi-media exploration of San Salvador's people, plants, sea life, culture and research project topics, Bahamas-Research

- Marine life around San Salvador island, photo gallery

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "San Salvador (1)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "San Salvador (1)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Real Life stories of San Salvador www.SanSal.info