San Pedro River (Arizona)

| San Pedro River | |

| Rio San Pedro,[1] Beaver River[2] | |

| stream | |

Fall colors, San Pedro RNCA | |

| Countries | Mexico, United States |

|---|---|

| States | Sonora, Arizona |

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Babocomari River |

| - right | Aravaipa Creek |

| Source | The Sierra Manzanal Mountains in northern Sonora |

| - location | North of Cananea, Mexico, Mexico |

| - elevation | 4,460 ft (1,359 m) |

| - coordinates | 31°12′04″N 110°12′28″W / 31.20111°N 110.20778°W [1] |

| Mouth | Confluence with the Gila River |

| - location | Winkelman, Arizona, Pinal County, United States |

| - elevation | 1,919 ft (585 m) |

| - coordinates | 32°59′04″N 110°47′01″W / 32.98444°N 110.78361°WCoordinates: 32°59′04″N 110°47′01″W / 32.98444°N 110.78361°W [1] |

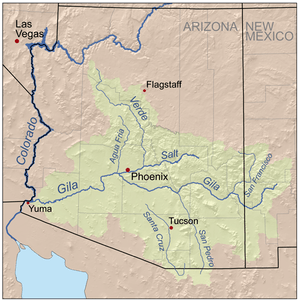

San Pedro River is a northward-flowing stream originating about 10 miles (16 km) south of the international border south of Sierra Vista, Arizona, in Cananea Municipality, Sonora, Mexico. The river starts at the confluence of other streams (Las Nutrias and El Sauz) just east of Sauceda, Cananea.[3] Within Arizona, the river flows 140 miles (230 km) north through Cochise County, Pima County, Graham County, and Pinal County to its confluence with the Gila River, at Winkelman, Arizona. It is the last major, free-flowing undammed river in the American Southwest,[4] it is of major ecological importance as it hosts two-thirds of the avian diversity in the United States, including 100 species of breeding birds and 300 species of migrating birds.[5]

History

The first people to enter the San Pedro Valley were the Clovis people who hunted mammoth here from 10,000 years ago. The San Pedro Valley has the highest concentration of Clovis sites in North America.[6] Some Clovis sites of note are the Lehner Mammoth-Kill Site, the Murray Springs Clovis Site and the Naco Mammoth-Kill Site.

The hunter-gatherer, Cochise Culture next made this area home between about 5000 to 200 BC. Followed by the more advanced Mogollon, Hohokam and Salado cultures who built permanent homes and engaged in agriculture here. By the time the first Europeans arrived these cultures had disappeared and the San Pedro River was home to the Sobaipuri people.

The first Europeans to visit the San Pedro River may have been the parties of Cabeza de Vaca, Fray Marcos de Niza or the Coronado expedition, and while no archeological evidence as yet exists of the passing of these groups, it has been fairly firmly established that the upper San Pedro was a widely recognized and utilized leg of the "Cibola Trail."[7] The Jesuit priest Eusebio Kino visited the villages along the San Pedro and Babocomari Rivers in 1692 and soon after introduced the first livestock to this area (if we assume that Coronado's livestock did not survive/breed).[8]

It is widely believed that by 1762 Apache depredation drove the Sobaipuri and Spanish out of the San Pedro Valley which then remained largely uninhabited until the early 1800s.[9] This, however, is not true as a recent study has shown.[10] In fact, documents state that not all the Sobaipuri left and in the 1780s Sobaipuri were noted still living along the river. Archaeology has confirmed additional Sobaipuri settlements along the middle San Pedro not mentioned in the documentary record throughout the 1800s.

Early American exploration of the San Pedro River, like most rivers in western North America, was driven by the pursuit of beaver pelts. James Ohio Pattie and his father led a party of fur trappers down the Gila River and then down the San Pedro River in 1826 which was so successful that he called the San Pedro the Beaver River.[2] The party was attacked by Apache Indians (probably the Aravaipa Band) at "Battle Hill" (probably Modern-day Malpais Hill) where they subsequently stashed and lost over 200 beaver pelts.[11] In the 19th century the river was a meandering stream with fluvial marshlands, riparian forest, Sporobolus grasslands and extensive beaver ponds. As the region experienced a rapid climate warming and drying,[12] (coincident with beaver removal and large-scale cattle introduction; correlation not directly established) the river down-cut and then widened in a process of arroyo formation observed on many rivers in the Southwest.[13] In 1895, J. A. Allen described a mammal collection from southeastern Arizona, "On the headwaters of the San Pedro, in Sonora, a colony of a dozen or more had their lodges up to 1893, when a trapper nearly exterminated them. All the streams in the White Mountains have beaver dams in them, although most of the animals have been trapped."[14] The beaver were finally extirpated by 1920s dynamiting of the beaver dams from soldiers from Fort Huachuca to prevent malaria.(citation?) By the mid-20th century the once perennial river only flowed during the rainy season and beaver, fluvial marshlands and Sporobolus grasslands were uncommon.[13][15] Physician naturalist Edgar Alexander Mearns' 1907 Mammals of the Mexican boundary of the United States reported beaver (Castor canadensis) on the San Pedro River and the Babocomari River.[16] Mearns claimed that the San Pedro River beaver represented a new subspecies Castor canadensis frondator or "Sonora beaver" that ranged from Mexico up to Wyoming and Montana.[17]

Ecology

The San Pedro River is the central corridor of the Madrean Archipelago of "Sky Islands", high mountains with unique ecosystems different from the ecology of the Sonoran desert "seas" that surround it.[18]

More than 300 species of birds, 200 species of butterflies and 20 species of bats use this corridor as they migrate between South, Central and North America, including the imperiled yellow-billed cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus). More than 80 species of mammals, including jaguar (Panthera onca), coatimundi (Nasua narica), bats, beaver (Castor canadensis frontador), mountain lion, and many rodents; more than 65 species of reptiles and amphibians, including Sonoran tiger salamander (Ambystoma mavortium stebbinsi) and western barking frog (Eleutherodactylus augusti). Remaining native fish species include the Gila chub (Gila intermedia) which is proposed for federal listing as endangered, and the longfin dace, desert sucker, roundtail chub, Sonora sucker, and speckled dace. The flora includes Fremont cottonwood (Populus fremontii), Goodding willow (Salix gracilistyla), velvet mesquite, sacaton, and the Federally endangered Huachuca water umbel (Lilaeopsis schaffneriana spp. recurva).[5]

In recent decades, rapid growth and population increases in southern Arizona has caused concern with this river. Several non-profit organizations have risen in recent years to raise awareness of this problem. The San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area (SPRNCA) was established in 1988 to protect some forty miles of the upper San Pedro valley.[19] The Nature Conservancy also owns several preserves in the watershed, including the San Pedro River Preserve, Aravaipa Canyon Preserve, Muleshoe Ranch Preserve, Ramsey Canyon Preserve, and most recently, Rancho Los Fresnos. Rancho Los Fresnos, near the river's source, is the largest ciénega, an isolated desert spring or marsh, remaining in the San Pedro River watershed. Its protection is important as 99% of the ciénegas in the Southwest have been drained and destroyed.[20]

With large portions of the river dry much of the year, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) wildlife biologist Mark Fredlake proposed restoring beaver to the watershed to retain water flows into the dry season and to support re-growth of the historic riparian vegetation.[15] Riparian habitat covers only 1% of the Southwest but supports 50% of breeding bird species and is vital as a food source for migrating avifauna.[21] Fredlake reasoned that beaver dams would raise the water table, allowing groundwater to recharge the river's flow in the dry season. From 1999 to 2002, 19 beavers were released into the SPRNCA, a 40-mile (64 km) stretch of the river, in Cochise County. By 2006 there were more than 30 dams. The beavers also dispersed widely and rapidly. One beaver migrated to Aravaipa Canyon, more than 100 rivermiles away; another to the river's terminus at the Gila River, earning itself the moniker “the surfing beaver”; and others up into Mexico, building several dams along the river’s upper tributaries. The program was successful with measurable increases in bird diversity and formation of deep pools and lasting flows.[22] In 2008, flooding destroyed all the beaver dams and this was followed by a long drought. However, as in historic times the beaver seems well adapted to the San Pedro River, and the 2009 dam count is back above 30 with a current population between 30 and 120 beavers.[15] A short video reviews the use of re-introduced beaver to restore the river.[23] In the upper river, re-introduced beavers have created willow and pool habitat which has extended the range of the endangered Southwestern willow flycatcher (Empidonax trailii extimus) with the southernmost verifiable nest recorded there in 2005.[24]

Watershed

The San Pedro drains an area of approximately 4,720 square miles (12,200 km2) in Cochise, Graham, Pima, and Pinal Counties. Its course traverses deep sedimentary basins flanked by the Huachuca, Mule, Whetstone, Dragoon, Rincon, Little Rincon, Winchester, Galiuro, Tortilla, and Santa Catalina Mountains. The San Pedro is fed by numerous tributaries, which in general, drain relatively short and steep catchments oriented more or less perpendicular to the mainstem.[25] For most of its length the San Pedro flows over sedimentary basin fill deposits, although it is bound by bedrock at the Tombstone Hills at Charleston and near Fairbank, “the Narrows” south of Cascabel, near Redington, and again at Dudleyville (Heindl, 1952). Two major tributaries, Babocomari River and Aravaipa Creek, each have extensive bedrock-lined stretches. Historically the San Pedro has been divided into upper and lower reaches at the Narrows.[26]

On May 27, 2011, a U.S. District judge ruled that Fort Huachaca's plan to pump 6,100 acre feet (7,500,000 m3) of groundwater without mitigation plans to replenish the San Pedro River flows failed to protect the endangered Southwestern willow flycatcher (Empidonax traillii) and the Huachuca water umbel will recover from their imperiled status. The ruling was in response to a second lawsuit brought by the Center for Biological Diversity and the Maricopa Audubon Society. In 2002, in response to an earlier suit filed by the center, another judge tossed out an earlier Wildlife Service biological opinion that the water pumping could be mitigated.[4]

Mormon Battalion

The Mormon Battalion marched through the river valley in 1846, and the only battle the battalion fought in their journey to California occurred near the river. The battalion's presence had aroused curiosity among a number of wild cattle, and the bulls of these herds damaged wagons and injured mules. In response, the men shot dozens of the charging bulls.[27] Mormon settlers later returned to this area in 1877 to found a settlement that became St. David, and logged the Huachuca Mountains to provide lumber for building Fort Huachuca and Tombstone.[28]

Geology, paleontology

The San Pedro Valley is a site for Holocene mammal fossils because of the riparian environment.

In recent decades, the Arizona Geological Society has focused on the region, as well as researchers. Development pressures, recreation, and groundwater harvesting have led to recent concerns of protecting the region. A recent floodplain study focused on the Holocene floodplain alluvium and its history, over a 125-mile (201 km) stretch of the river to understand subground waterflow resources.[26]

See also

- San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area

- List of Arizona rivers

- List of tributaries of the Colorado River

- From Desert to Sky Islands

References

- 1 2 3 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: San Pedro River

- 1 2 David J. Weber (2005). The Taos Trappers: The Fur Trade in the Far Southwest, 1540-1846. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8061-1702-7. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ Nogales, Arizona, 30x60 Topographic Quadrangle, USGS, 994

- 1 2 Tony Davis (2011-06-01). "Ruling faults analysis of pumping, San Pedro". Arizona Star. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- 1 2 "San Pedro River, Arizona". The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ "SURVEY OF THE UPPER SAN PEDRO VALLEY ARIZONA AND SONORA, MEXICO". Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- ↑ Flint, Richard and Shirley. The Latest Word from 1540.

- ↑ "Huachuca Illustrated, A Magazine of the Fort Huachuca Museum, Vol. 4 1999" (PDF). U.S. ARMY, FORT HUACHUCA. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Aravaipa Canyon Wilderness Prehistory and History". U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- ↑ Seymour, Deni (Summer 2011). "1762 On the San Pedro: Reevaluating Sobaípuri-O'odham Abandonment and New Apache Raiding Corridors". The Journal of Arizona History. 52 (2): 169–188.

- ↑ Batman, Richard (1984). American Ecclesiastes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- ↑ Turner, Webb. The Changing Mile. University of Arizona Press.

- 1 2 Gabrielle L. Katz, J. C. Stromberg, M. W. Denslow (2009). "Streamside herbaceous vegetation response to hydrologic restoration on the San Pedro River, Arizona". Ecohydrology. 2 (2): 213–225. doi:10.1002/eco.62.

- ↑ J. A. Allen (1895). "On a Collection of Mammals from Arizona and Mexico, Made by Mr. W. W. Price" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- 1 2 3 Paul Young (May 27, 2010). "Environmental Engineers: Beaver on the San Pedro River". Desert Leaf. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ Edgar Alexander Mearns (1907). Mammals of the Mexican boundary of the United States: A descriptive catalogue of the species of mammals occurring in that region; with a general summary of the natural history, and a list of trees. Government Printing Office. p. 359. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ↑ Edgar A. Mearns (1897). "Preliminary Diagnosis of the New Mammals of the Genera Sciurus, Castor, Neotoma, and Sigmodon, from the Mexican Border of the United States" (PDF). Proceedings U.S. National Museum. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "San Pedro River Ecology". San Pedro River Valley Organization. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ "The San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area". US Dept. of the Interior. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ "Rancho Los Fresnos and the San Pedro River". The Nature Conservancy. 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ Susan K. Skagen, Rob Hazlewood, and Michael L. Scott (2005). The Importance and Future Condition of Western Riparian Ecosystems as Migratory Bird Habitat (PDF). USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-191 (Report). pp. 525–527. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ Glenn Johnson and Dr. Charles van Riper III (2007). Influence of Beaver Activity, Vegetation Structure, and Surface Water on Riparian Bird Communities along the Upper San Pedro River, Arizona (PDF) (Report). School of Natural Resources, University of Arizona, USGS Sonoran Desert Research Station. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ MIke Foster (August 2011). "Reintroduction of the Beaver to the San Pedro River of Southeastern Arizona". Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ↑ Johnson, Glenn E., and van Riper III, Charles (2014). Effects of reintroduced beaver (Castor canadensis) on riparian bird community structure along the upper San Pedro River, southeastern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- ↑ Huckleberry G, Lite SJ, Katz GL, Pearthree P (2009). Stromberg JS, Tellman B, eds. Fluvial Geomorphology in Ecology and Conservation of the San Pedro River. Tucson,Arizona: University of Arizona Press.

- 1 2 Joseph P. Cook; et al. (2009). Mapping of Holocene River Alluvium along the San Pedro River, Aravaipa Creek, and Babocomari River, Southeastern Arizona (PDF) (Report). Arizona Geological Society. Retrieved 2015-01-01. Document repository for report map files

- ↑ Roberts, B.H. (1919). The Mormon Battalion: Its History and Achievements. Salt Lake City: Deseret News.

- ↑ Sue Kartchner (Feb 24, 2009). "Popular costume ball set Saturday". San Pedro Valley News Sun. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

External links

- Nature Conservancy Webpage

- Mountain Visions website writeup

- This page explores many features of the valley

- Aviatlas: Birding along San Pedro

- Center for Biological Diversity San Pedro River page

- Huachaca water umbel at Pima County website

Geology, groundwater, paleontology

- "Geology of the San Pedro River, Aravaipa Creek, and Babocomari River"

- Anti-development, (Bypass-route)