San Mateo Ixtatán

| San Mateo Ixtatán | |

|---|---|

| Municipality | |

|

View of San Mateo Ixtatán | |

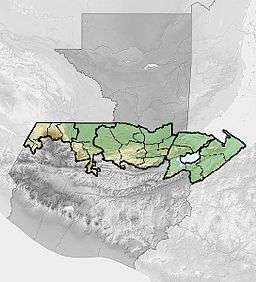

San Mateo Ixtatán Location in Guatemala | |

| Coordinates: 15°50′0″N 91°29′0″W / 15.83333°N 91.48333°W | |

| Country |

|

| Department |

|

| Municipality | San Mateo Ixtatán |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal |

| • Mayor | Andrés Alonzo Pascual[1] |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 560 km2 (220 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,540 m (8,330 ft) |

| Population (2013)[2] | |

| • Municipality | 49,993 |

| • Urban | 9,299 |

| • Ethnicities | Chuj, Ladino |

| • Religions | Roman Catholicism, Evangelicalism, Maya |

| Climate | Cfb |

| Website | http://sanmateoixtatan.gob.gt |

San Mateo Ixtatán is a municipality in the Guatemalan department of Huehuetenango. It is situated at 2,540 metres (8,330 ft) above sea level in the Cuchumatanes mountain range and covers 560 square kilometres (220 sq mi) of terrain. It has a cold climate and is located in a cloud forest. The temperature fluctuates between 0.5 and 20 °C (32.9 and 68.0 °F). The coldest months are from November to January and the warmest months are April and May. The town has a population of about 10,000, and is the municipal center for an additional 20,000 people living in the surrounding mountain villages. It has a weekly market on Thursday and Sunday. The annual town festival takes place from September 19 to September 21 honoring their patron Saint Matthew. The residents of San Mateo belong to the Chuj Maya ethnic group and speak the Mayan Chuj language, not to be confused with Chuj baths, or wood fired steam rooms that are common throughout the central and western highlands.

Etymology

The derivation of "Ixtatán" is uncertain. In Chuj, Ixta' = toy or doll; Ta'anh = lime, giving the translation of toy or doll of lime.[3] These lime dolls can be seen on the Catholic Church facade dating back to colonial times. According to historian Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán (1690), the name means “ Land of the Salt” from the words of Ystat = salt and teail = land. On the other hand, historian Jorge Luis Areola considers 'Ixtatán' to be from the Nahuatl language, from the words Ixtat = salt and tlan = close or nearby.

History

Colonial history

In 1529, four years after the Spanish conquest of Huehuetenango, San Mateo Ixtatán (then known by the name of Ystapalapán) was given in encomienda to the conquistador Gonzalo de Ovalle, a companion of Pedro de Alvarado, together with Santa Eulalia and Jacaltenango.[4][5] In 1549, the first reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán took place, overseen by Dominican missionaries.[4]

In the late 17th century, the Spanish missionary Fray Alonso De León reported that about eighty families in San Mateo Ixtatán did not pay tribute to the Spanish Crown or attend the Roman Catholic mass.[6] He described the inhabitants as quarrelsome and complained that they had built a pagan shrine in the hills among the ruins of precolumbian temples, where they burnt incense and offerings and sacrificed turkeys.[6] He reported that every March they built bonfires around wooden crosses about two leagues from the town and set them on fire.[6] Fray Alonso de León informed the colonial authorities that the practices of the natives were such that they were Christian in name only.[6] Eventually, Fray Alsonso De León was chased out of San Mateo Ixtatán by the locals.[6]

In 1684, a council led by Enrique Enriquez de Guzmán, the then governor of Guatemala, decided upon the reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán and nearby Santa Eulalia, both within the colonial administrative district of the Corregimiento of Huehuetenango.[7]

On 29 January 1686, captain Melchor Rodríguez Mazariegos, under orders of the governor, left Huehuetenango for San Mateo Ixtatán, where he recruited indigenous warriors from the nearby villages, with 61 from San Mateo itself.[8] It was believed by the Spanish colonial authorities that the inhabitants of San Mateo Ixtatán were friendly towards the still unconquered and fiercely hostile inhabitants of the Lacandon region, which included parts of what is now the Mexican state of Chiapas and the western part of the Petén Basin.[9] In order to prevent news of the Spanish advance reaching the inhabitants of the Lacandon area, the governor ordered the capture of three community leaders of San Mateo, named as Cristóbal Domingo, Alonso Delgado and Gaspar Jorge, and had them sent under guard to be imprisoned in Huehuetenango.[10] The governor himself arrived in San Mateo Ixtatán on 3 February, where captain Melchor Rodríguez Mazariegos was already awaiting him.[11] The governor ordered the captain to remain in the village to use it as a base of operations for penetrating the Lacandon region.[11] The Spanish missionaries Fray Diego de Rivas and Fray Pedro de la Concepción also remained in the town.[11] After this, governor Enrique Enriquez de Guzmán left San Mateo Ixtatán for Comitán in Chiapas, to enter the Lacandon region via Ocosingo.[12]

In 1695, a three-way invasion of the Lacandon was launched simultaneously from San Mateo Ixtatán, Cobán and Ocosingo.[13] Captain Melchor Rodriguez Mazariegos accompanied by Fray Diego de Rivas and 6 more missionaries together with 50 Spanish soldiers left Huehuetenango for San Mateo Ixtatán, managing to recruit 200 indigenous Maya warriors on the way; from Santa Eulalia, San Juan Solomá and San Mateo itself.[14] They followed the same route used in 1686.[15] On 28 February 1695, all three groups left their respective bases of operations to conquer the Lacandon.[14] The San Mateo group headed northeast into the Lacandon Jungle.[14]

The Dominican Order built the Catholic church in San Mateo, which fell within the parish of Soloma.[16]

Republican history

San Mateo Ixtatán was forced to give up some of their territory to create the municipality of Nentón in 1876 and it struggled to keep its communal lands. At the beginning of the 1900s, a law was enacted throughout Guatemala that the mayor and councilmen should be ladinos.

During the liberal government of Justo Rufino Barrios, extreme poverty and forced migrations to the southern coast created a lasting state of tension in the northern communities of Huehuetenango and specifically in San Mateo Ixtatán. The ladino coastal plantation owners sent contractors to San Mateo Ixtatán on market days. These contractors gave money to local people promising double or triple the amount if they came to work in their coffee and cotton plantations. The locals signed documents insuring their manual labor, but were essentially enslaved because the contracts were unjust and treatment inhumane.[17] On July 17, 1898, a plantation contractor was killed. To cover up the crime, 30 more ladinos were killed. One survived and informed the army who responded by killing 310 Chuj people from San Mateo Ixtatán.[18]

Franja Transversal del Norte

The Northern Transversal Strip was officially created during the government of General Carlos Arana Osorio in 1970, by Legislative Decree 60-70, for agricultural development.[19] The decree literally said: "It is of public interest and national emergency, the establishment of Agrarian Development Zones in the area included within the municipalities: San Ana Huista, San Antonio Huista, Nentón, Jacaltenango, San Mateo Ixtatán, and Santa Cruz Barillas in Huehuetenango; Chajul and San Miguel Uspantán in Quiché; Cobán, Chisec, San Pedro Carchá, Lanquín, Senahú, Cahabón and Chahal, in Alta Verapaz and the entire department of Izabal."[20]

Salt

Highly saturated salt water comes from the ground in several sacred wells. Historically, it is said that many traveled through San Mateo Ixtatán seeking the salt produced there. Many gather to pray in front of the wells to the goddess of salt, Atz’am. Women haul the salt-water up the long mountainside in plastic jugs where they use it as is or boil it to make a tasty, white salt. The salt is most famous as K'ik' Atz'am, Sal Negra or black salt. This is made by a few women in the town by adding a secret ingredient to the salt water as it boils. The black salt is very tasty and highly prized. It is said to have curative powers for the treatment of stomach ailments and headache.

The well is managed by the mayor’s office and is open from Monday through Saturday from 1 to 5 pm.

Archaeological sites

Within the town of San Mateo Ixtatán, there are protected, but not excavated archaeological sites. The largest one is known as Yol K'u meaning within the sun or Wajxaklajun meaning eighteen.[21] It is spectacularly situated on a promontory, surrounded by four large mounds. It is said to have been an astronomical temple. Another, K'atepan,[22] can be seen from Yol K'u on the other side of the valley and means old temple in the Chuj language. It lies just north of San Mateo.[21]

The archaeological site of Curvao at San Mateo Ixtatán has been dated to the Classic Period.[23]

Clothing

Traditional clothing of San Mateo Ixtatán for men and women is still seen within the community. The men use a woolen capixay. It is made of two woven pieces of brown or black sheep's wool, sewn together on the sides leaving the sleeves open for the arms.[24] The women traditionally wear a corte or long, Mayan wrap-around skirt. It is generally a bright red base patterned with white, yellow and green stripes. Cotton scarves are tied in their hair. The woman's huipil or top is a brightly multi-colored, hand-woven cotton poncho with a lacy collar.[24] It is said that a full-size huipil from San Mateo Ixtatán takes about 9 months to a year to make.

Climate

San Mateo Ixtatán has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb).

| Climate data for San Mateo Ixtatán | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.8 (55) |

12.9 (55.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

14.9 (58.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.9 (57) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38 (1.5) |

27 (1.06) |

37 (1.46) |

77 (3.03) |

118 (4.65) |

260 (10.24) |

172 (6.77) |

171 (6.73) |

214 (8.43) |

179 (7.05) |

82 (3.23) |

36 (1.42) |

1,411 (55.57) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[25] | |||||||||||||

Geographic location

See also

-

Guatemala portal

Guatemala portal -

Geography portal

Geography portal - Franja Transversal del Norte

Notes and references

- ↑ "Alcaldes electos en el departamento de Huehuetenango". Municipalidades de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala. 9 October 2015. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ "XI Censo Nacional de Poblacion y VI de Habitación (Censo 2002)". INE. 2002.

- ↑ Stzolalil Stz'ib'chaj Heb' Chuj, ALMG, 2007, p. 32

- 1 2 San Mateo Ixtatán at Inforpressca (in Spanish)

- ↑ MINEDUC 2001, pp. 14–15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lovell 2000, pp. 416–417.

- ↑ Pons Sáez 1997, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Pons Sáez 1997, pp. XXXIII,153–154.

- ↑ Pons Sáez 1997, p. 154.

- ↑ Pons Sáez 1997, pp. 154–155.

- 1 2 3 Pons Sáez 1997, p. 156.

- ↑ Pons Sáez 1997, pp. 156, 160.

- ↑ Pons Sáez 1997, pp.XXXIII.

- 1 2 3 Pons Sáez 1997, p. XXXIV.

- ↑ Pons Sáez 1997, p. XXXIII.

- ↑ MINEDUC 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Workshop from the PROPAZ organization, Sept. 10, 2008

- ↑ la Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico (CEH)

- ↑ "Franja Transversal del Norte". Wikiguate. Guatemala. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ Solano 2012, p. 15.

- 1 2 MINEDUC 2001, p. 18.

- ↑ ALMG and the Comunidad Lingüística Chuj, 2006, p. 243

- ↑ MINEDUC 2001, p. 12.

- 1 2 Stzolalil Stz'ib'chaj Heb' Chuj, ALMG, 2007, p. 33

- ↑ "Climate:San Mateo Ixtatán". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ↑ SEGEPLAN. "Municipios del departamento de Huehuetenango" (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

Bibliography

- ALMG; the Comunidad Lingüística Chuj (2006). Yumal skuychaj ti' Chuj / Gramática pedagógica Chuj (in Chuj and Spanish). Guatemala: Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG). OCLC 226958677.

- Lovell, W. George (2000). "The Highland Maya". In Richard E.W. Adams; Murdo J. Macleod. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 392–444. ISBN 0-521-65204-9. OCLC 33359444.

- MINEDUC (2001). Eleuterio Cahuec del Valle, ed. Historia y Memorias de la Comunidad Étnica Chuj (PDF) (in Spanish). II (Versión escolar ed.). Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar/UNICEF/FODIGUA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-05.

- Pons Sáez, Nuria (1997). La Conquista del Lacandón (in Spanish). Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ISBN 968-36-6150-5. OCLC 40857165.

- Solano, Luis (2012). "Contextualización histórica de la Franja Transversal del Norte (FTN)" (PDF). Centro de Estudios y Documentación de la Frontera Occidental de Guatemala, CEDFOG (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 October 2014.

Further reading

- Ku'in Maltin Tunhku Ku'in; Comunidad Lingüística Chuj (2007). Stzolalil stz'ib'chaj ti' Chuj = Gramática normativa Chuj (in Chuj and Spanish). Guatemala: Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala. OCLC 227209552.

- — (2007). Stzolalil sloloni-spaxtini heb' Chuj = Gramática descriptiva Chuj (in Chuj and Spanish). Guatemala: Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala. OCLC 310122456.

External links

-

Media related to San Mateo Ixtatán at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to San Mateo Ixtatán at Wikimedia Commons - Municipality in Spanish

- Ixtatan Foundation Charlottesville, Virginia based non-profit that works in San Mateo Ixtatán

- Academia de las Lenguas Mayas

- INGUAT

- Satellite Map of San Mateo Ixtatán

- Prensa Libre Revista D De la sal a los dólares A news article in Spanish about how San Mateo Ixtatán is changing.

Coordinates: 15°50′N 91°29′W / 15.833°N 91.483°W