San Francisco Committee of Vigilance

The San Francisco Committee of Vigilance was formed in 1851. The catalyst for its formation was the criminality of the Sydney Ducks,[1] it was revived in 1856 in response to rampant crime and corruption in the municipal government of San Francisco, California. The need for extralegal intervention was apparent with the explosive population growth following the discovery of gold in 1848. The small town of about 900 individuals grew to a booming city of over 200,000 very rapidly.[2] This overwhelming growth in population made it nearly impossible for the previously established law enforcement to regulate any longer which resulted in the organization of vigilantes.

These militias hanged eight people and forced several elected officials to resign. Each Committee of Vigilance formally relinquished power after three months.

1851

The 1851 Committee of Vigilance was inaugurated on June 9 with the promulgation of a written doctrine declaring its aims[3] and hanged John Jenkins of Sydney, Australia on June 10 after he was convicted of stealing a safe from an office in a trial organized by the committee: grand larceny was punishable by death under California law at the time.[4] The June 13 Daily Alta California printed this statement:

| “ | WHEREAS it has become apparent to the citizens of San Francisco, that there is no security for life and property, either under the regulations of society as it at present exists, or under the law as now administered; Therefore the citizens, whose names are hereunto attached, do unit themselves into an association for the maintenance of the peace and good order of society, and the preservation of the lives and property of the citizens of San Francisco, and do bind ourselves, each unto the other, to do and perform every lawful act for the maintenance of law and order, and to sustain the laws when faithfully and properly administered; but we are determined that no thief, burglar, incendiary or assassin, shall escape punishment, either by the quibbles of the law, the insecurity of prisons. the carelessness or corruption of the police, or a laxity of those who pretend to administer justice. | ” |

It boasted a membership of 700 and claimed to operate in parallel to, and in defiance of, the duly constituted city government. Committee members used its headquarters for the interrogation and incarceration of suspects who were denied the benefits of due process. The Committee engaged in policing, investigating disreputable boarding houses and vessels, deporting immigrants, and parading its militia. Four people were hanged by the Committee; one was whipped (a common punishment at that time); fourteen were deported to Australia; fourteen were informally ordered to leave California; fifteen were handed over to public authorities; and forty-one were discharged. The 1851 Committee of Vigilance was dissolved during the September elections, but its executive members continued to meet into 1853.[5]

A total of four were executed: John Jenkens, an Australian from Sydney accused of burglary, who was hanged on June 10, 1851; James Stuart, also from Sydney and accused of murder, who was hanged on July 11, 1851; and Samuel Whittaker and Robert McKenzie, associates of Stuart accused of "various heinous crimes", who were hanged on August 24, 1851. The lynching of Whittaker and McKenzie occurred three days after a standoff between the Committee and the nascent police force trying to protect the prisoners; the Committee nabbed Whittaker and McKenzie after storming the jail during Sunday church services.[6]

The Committee offered a $5,000 reward for the capture of anyone found guilty of arson, and committee members patrolled the streets at night to watch for fires. After these actions were taken, fires in San Francisco diminished noticeably.[7]

1856

The Committee of Vigilance was reorganized on 14 May 1856 by many of the leaders from the first one and adopted an amended version of the 1851 constitution.[5] Unlike the earlier Committee, and the vigilante tradition generally, the 1856 Committee was concerned with not only civil crimes but also politics and political corruption.[5] The catalyst for the Committee was a murder, in the guise of a political duel in which James P. Casey shot opposition newspaper editor James King of William. King, along with many San Francisco residents were outraged by Casey's appointment to the city board of supervisors and believed that the election had been rigged.The motivation behind this murder came from King's publishing in the "Daily Evening Bulletin", an article accusing Casey of illegal activities.[8] The combination of the political unrest surrounding the election and the article, resulted in Casey's shooting of James King.

The 1856 Committee was also much larger than the Committee of 1851, claiming 6,000 in its ranks. The Committee worked very closely with the formal government of San Francisco. President of the vigilance committee, William T. Coleman was a close friend of Governor J. Neely Johnson and the two men met on several occasions working towards the shared goal of stabilizing the town.[9] Another important figure at this time who would later come to make a name for himself in the Civil War is William T. Sherman. Sherman was running a bank when Governor Johnson requested he become the commander of the San Francisco branch of the state militia. Sherman accepted the position two days before the murder of King by Casey[10]

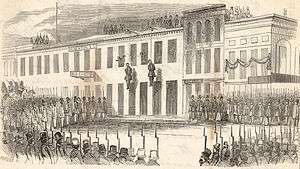

The 1856 Committee of Vigilance dissolved on 11 August 1856, and marked the occasion with a “Grand Parade.”[5]

Political power in San Francisco was transferred to a new political party established by the vigilantes, the People's Party, which ruled until 1867 and was eventually absorbed into the Republican Party. The vigilantes had thus succeeded in their objective of usurping power from the Democratic Party machine that hitherto dominated civic politics in the city.[11] Notable people included William Tell Coleman, Martin J. Burke, San Francisco mayor Henry F. Teschemacher, and San Francisco's first chief of police James F. Curtis.

Vigilante headquarters in 1856 consisted of assembly halls, meeting rooms, a military kitchen and armory, an infirmary, and prison cells, all of which were fortified with gunny sacks and cannons.[5] Four people were officially executed again in 1856, but the death toll also includes James “Yankee” Sullivan, an Irish immigrant and professional boxer who killed himself after being terrorized and detained in a Vigilante cell.[5][12]

The 1856 Committee also engaged in policing, investigations, and secret trials, but it far exceeded its predecessor in audacity and rebelliousness. Most notably, it seized three shipments of armaments intended for the state militia and tried the chief justice of the California Supreme Court.[5] The Committee’s authority, however, was bolstered by almost all militia units in the city, including the California Guards.[5]

Controversy

From the Daily Evening Bulletin, James King of William, Editor. May 14, 1856:

Among the names mentioned by ”a purifier,” in his communication of Friday last, as objectionable appointments of the Custom House, was that of Mr. Bagley, who has since called on us, and by whose request we have made more particular inquiries into the charges made against him. On Monday we told Mr. Bagley that we could not feel justified in withdrawing the general charge against him, for though in the particular cases mentioned we had not been satisfied that he was the party at fault, yet the general character we heard was against him. To this Mr. Bagley urged that our informants were all enemies of his, which, in one sense of the word, is true, though they are not the persons he supposes. At our last interview with Mr. B. we told him that if he could bring some respectable persons, known to us, who would vouch for him, and explain away what had been told to us, we would take pleasure in saying as much in our paper.

Several such have called on us, but whilst they are unanimous in saying that Bagley behaves himself very well at present, yet when we ask them, for instance, about the fight with Casey, they cannot explain satisfactorily. Our impression at the time was, that in the Casey fight Bagley was the aggressor. It does not matter how bad a man Casey had been, nor how much benefit it might be to the public to have him out of the way, we cannot accord to any one citizen the right to kill, or even beat him, without personal provocation. The fact that Casey has been an inmate of Sing Sing prison in New York, is no offence against the laws of this State; nor is the fact of his having stuffed himself through the ballot box as elected to the Board of Supervisors from a district where it is said he was not even a candidate, any justification for Mr. Bagley to shoot Casey, however richly the latter may deserve to have his neck stretched for such fraud on the people. These are acts against the public good, not against Mr. Bagley in particular, and however much we may detest Casey’s former character, or to be convinced of the shallowness of his promised reformation, we cannot justify the assumption by Mr. Bagley to take upon himself the redressing of these wrongs. This case of Bagley’s has caused us much anxiety, and we should have been pleased to have withdrawn cheerfully his name from the list alluded to, but we cannot conscientiously do more than express our gratification at the assurances we get of his present conduct, in which we trust he will persevere. As to Casey fight, we suggest to Mr. Bagley if he can explain that away, it would not be amiss to do so, and he can have the use of our columns for that purpose.

There remains historical controversy about the vigilance movements. For example, both Charles Cora and James Casey were hanged in 1856 as murderers by the Committee of Vigilance: Cora shot and killed a U.S. Marshal William H. Richardson who had drunkenly insulted Cora's mistress, Belle Cora,[13] and Casey killed James King, editor of rival newspaper The Evening Bulletin, for publishing an editorial that exposed Casey's criminal record in New York.[14]

King had also denounced the corruption of City Officials who he believed had let Cora off the hook for the murder of William Richardson: Cora's first trial had ended in a hung jury, and there were rumors that the jury had been bribed. Casey's friends sneaked him into the jail precisely because they were afraid that he would be hanged. This hanging may have been a response by frustrated citizens to ineffectual law enforcement, or a belief that due process would result in acquittals. Popular histories have accepted the former view: that the illegality and brutality of the vigilantes was justified by the need to establish law and order in the city.

One prominent critic of the San Francisco vigilantes was General W. T. Sherman, who resigned from his position as Major-general of the Second Division of Militia in San Francisco. In his memoirs, Sherman wrote:

As [the vigilantes] controlled the press, they wrote their own history, and the world generally gives them the credit of having purged San Francisco of rowdies and roughs; but their success has given great stimulus to a dangerous principle, that would at any time justify the mob in seizing all the power of government; and who is to say that the Vigilance Committee may not be composed of the worst, instead of the best, elements of a community? Indeed, in San Francisco, as soon as it was demonstrated that the real power had passed from the City Hall to the committee room, the same set of bailiffs, constables, and rowdies that had infested the City Hall were found in the employment of the "Vigilantes."[15]

Influence in British Columbian affairs

A former member of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance, physician Max Fifer, moved to Yale, British Columbia at the time of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush, and participated in the organization of a Vigilance Committee on the Fraser River in 1858 to address issues of lawlessness and a vacuum of effective governmental authority created by the sudden influx of goldseekers to the new British colony.[16] The Vigilance Committee, which in San Francisco had persecuted disgraced Philadelphia lawyer Ned McGowan, played a role in the bloodless McGowan's War on the lower Fraser in 1858–1859. At the end of the so-called 'War', McGowan was convicted by Judge Matthew Baillie Begbie of an assault against Fifer in British Columbia[17] but McGowan's defense statement, which described some of the activities of the San Francisco vigilantes and his own personal experience of vigilantism, impressed and disturbed Begbie who, like Colonial Governor James Douglas was determined to prevent conditions in the goldfields of British Columbia from deteriorating into mob rule.[18]

In popular culture

Death Valley Days: Episode: "The Battle of San Francisco Bay"

See also

- Sydney Ducks

- Samuel Brannan

- William Tell Coleman

- McGowan's War

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

References

- ↑ Herbert Asbury. "Sydney Ducks" in The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld Basic Books, 1933

- ↑ "Second vigilante committee organizes in San Francisco". History.com. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ↑ The Rivals: William Gwin, David Broderick, and the Birth of California By Arthur Quinn, 1997, p. 109

- ↑ Johnson, John. Historic US Court Cases. Pg. 49. Routelidge, 2001

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ethington, Philip J. (2001). The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850-1900. Berekely, CA: University of California Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 0-520-23001-9. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ Hittell, T.H. History of California Vol 3 (1897), pp. 313-330.

- ↑ Gordon Morris Bakken, Law in the western United States, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 2000, p. 110.

- ↑ Kamiya, Gary (August 1, 2014). "1856 Vigilantes Changed Corrupt Political System". SFGate. Hearst. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ↑ "William Tecumseh Sherman". Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ↑ "General Sherman and the 1856 Committee of Vigilance". Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ↑ Ethington, Philip J. (Winter 1987). "Vigilantes and the Police: The Creation of a Professional Police Bureaucracy in San Francisco, 1847-1900". Journal of Social History. 21 (2): 197–227. JSTOR 3788141. doi:10.1353/jsh/21.2.197.

- ↑ Asbury, Herbert (1933). History of the Barbary Coast - An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld. Alfred A Knopf. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ Asbury, Herbert. The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld. p. 84. Basic Books, 2002.

- ↑ Asbury, Herbert. The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld. pp. 86–87. Basic Books, 2002.

- ↑

- ↑ Donald J. Hauka, McGowan's War, Vancouver: New Start Books, 2003, p. 136

- ↑ Hauka, p. 180

- ↑ Hauka, p. 182

Bibliography

- Myers, John Myers, San Francisco's Reign of Terror. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, 1966

- John Boessenecker, ed. Against the Vigilantes: The Recollections of Dutch Charley Duane. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999. (Review)

- Quinn, Arthur, The Rivals: William Gwin, David Broderick, and the Birth of California, Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-8032-8851-5

- Hauka, Donald J., McGowan's War, Vancouver: New Start Books, 2003. ISBN 1554200016 ISBN 978-1554200016 (excerpt)

- Stewart, George R., Committee of Vigilance; Revolution in San Francisco, 1851. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1964.

- Hittell, T.H. History of California, Vol. 3, 1897

- Nancy J. Taniguchi, Land, Violence, and the 1856 San Francisco Vigilance Committee, 2016.

External links

- William Tecumseh Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Volume 1 reprinted 1917. (Discussion of 1856 vigilante activities) (books.google) (tufts.edu)

- Edward McGowan, Narrative of Edward McGowan, including a full account of the author's adventures and perils while persecuted by the San Francisco vigilance committee of 1856, together with a report of his trial, which resulted in his acquittal. San Francisco, CA: self-published, 1857, reprinted 1917.

- Frank Meriweather Smith, San Francisco vigilance committee of '56 : with some interesting sketches of events succeeding 1846. San Francisco, CA: Barry, Baird & Co., 1883.

- Kevin Mullen, "Malachi Fallon: First Chief of Police" from the Encyclopedia of San Francisco.

- Committees of Vigilance (Primary sources) from the Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco.

- Mary Floyd Williams, History of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance: A Study of Social Control on the California Frontier in the Days of the Gold Rush, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1921. (Thesis (Ph.D.) - University of California, 1919)

- Mary Floyd Williams, History of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance: A Study of Social Control on the California Frontier in the Days of the Gold Rush, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1921.

- James O'Meara, The Vigilance Committee of 1856 San Francisco : James H. Barry, 1887.

- Royce, Josiah, (1855-1916) California, from the conquest of 1846 to the second vigilance committee in San Francisco - A study of American character, 1892.

- Charles James King, the vigilance committees NEW YORK : THE LEWIS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1905.

- George H. Tinkham, EXCITING EVENTS FROM 1850-56 from California Men and Events 1769-1890 Panama-Pacific Exposition Edition. 1915.

- Hubert Howe Bancroft, Popular Tribunals Volume I and Popular Tribunals Volume II. San Francisco: The History Company, 1887.

- Guide to the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851 Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Guide to the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1856 Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Papers of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851, Volume I University of California, 1910

- Papers of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851, Volume II University of California

- Papers of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851, Volume III University of California, 1919.

- San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851 - WorldCat Identities

- San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1856 - WorldCat Identities