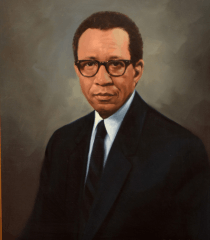

Samuel Woodrow Williams

| Samuel Woodrow Williams | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 12, 1912 |

| Died | October 10, 1970 (aged 58) |

| Education | Morehouse College, Howard University |

| Occupation | Minister, Professor, Activist |

| Home town | Chicot County, Arkansas |

| Movement | Civil Rights Movement |

| Awards | NAACP Meritorious award, Phi beta sigma citizenship award |

Samuel Woodrow Williams was an African American Baptist minister, professor of philosophy and religion, and Civil Rights activist. Williams was born on February 12, 1912 in Sparkman (Dallas County) then grew up in Chicot County, Arkansas. Samuel Woodrow Williams attended Morehouse College where he received his bachelors in philosophy and later attended Howard University earning his masters of divinity.

Williams aided in the Atlanta Student Movement and helped found both the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) and the Atlanta Summit Leadership Council, which then helped to organize the Atlanta branch of the Community Relations Commission (CRC). Simultaneously he was co-chairman of the Atlanta Summit Leadership Conference and acting president of the Atlanta Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1947, Williams became pastor at Friendship Baptist Church and lectured at more than 20 colleges and universities throughout the South preaching that men should lead their lives through principle and moral awareness. In his final years of life Williams expanded his sermons to focus on a non-violent approach, arguing that society is a slave to social systems, social patterns, and burdened by the anxiety to destroy one another.[1] This message was conveyed through a sermon that he dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr, entitled “He was no Criminal,” in 1969.[2]

Williams died from complications as a result of a major operation.

Early life

Samuel Woodrow Williams was born the quiet county of Sparkman (Dallas County) in Little Rock, Arkansas . He was born on February 12, 1912 as the oldest of eight children of Arthur William and Annie Willie Butler Williams. Growing up Williams enjoyed hunting, fishing, playing basketball and baseball as well as reading and writing.[2]

Education

In 1932-1933 he attended the historically black Philander Smith College in Little Rock and then transferred to Morehouse College in Atlanta, Ga. At Morehouse College, Williams received his Bachelor of Arts Degree in Philosophy in 1937. Williams went on earn his masters of divinity from Howard University from 1938-1942 where he was studied under Dr. Alain Locke and Dr. Benjamin E. Mays.

From there Williams undertook doctoral studies at University of Chicago but did not complete his doctorate program. However, he received an honorary doctorate from Arkansas Baptist Church in 1960.

Morehouse College

After completing his formal educations Williams joined the faculty of Morehouse College in 1946 as the chair of the Department of Philosophy and Religion. As chair of the department he wrote annual reports to the president and lead meetings on the improvement of the department and college as a whole.[2] In 1963, Williams, as the head of the Department of Religion, expressed his concerns that there was only a minor in religion and of the absence of an honors program for the department. Williams wanted Morehouse to have religion at the center of its programs.[3]

During his time at Morehouse, Williams earned a reputation of intellectually rigorous and demanding of his students.[3] While teaching at Morehouse, Williams mentored the president of Samuel DuBois Cook who later become the president of Dillard University and the first black mayor of Atlanta, Maynard Jackson. Williams is also credited as mentor and former teacher of Martin Luther King Jr., leader in the Civil Rights Movement.[1]

NAACP

In the 1950s Williams began his association with the Atlanta branch of the NAACP. He joined the executive branch and later became president in 1957.

During his time as president WIlliams engaged in his first legal battle. In January 1958 the NAACP filed suit against the Atlanta school board and forced it to begin the long and difficult process of compliance with Brown v. Board of Education. Later on Williams, having been w by the Montgomery Bus Boycott, filed a suit against the segregated Atlanta trolley system with Reverend John Porter and won in 1959.[4] Williams and the NAACP put into practice education reform, desegregation of hotels and restaurants, and challenging hotel misconduct and use of discrimination.

Atlanta Student Movement

Williams played a key role in the Atlanta Student Movement. The movement was characterized by an appeal that composed both their complaints as well as their desired goals for proposed change.[2] Williams was one of the adults that encouraged students to draft “An Appeal for Human Rights,” the manifesto of the Atlanta Student Movement.[2] This appeal was published in early March 1960 in the Atlanta newspapers[5] and the New York Times.[4]

As the NAACP president Williams pledged full support to this act of civil resistance. They conducted a nonviolent protest and civil disobedience that produced productive dialogues between activists and government authorities. Forms of protest and/or civil disobedience included boycotts and sit ins that contributed to the Civil Rights Movement.[6]

During the same year Williams became a founding member and a vice president of the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC).

The SCLC is an African American Civil Rights organization that began in 1957. SCLC's goal is to form an organization whose trademark is of peace and non-violence. Although during the initial years of operation, leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Williams encountered repression from white organization, police and the Ku Klux Klan. SCLC advocates for the involvement of churches in political activism. Members of the SCLC were harassed, threatened and attacked, yet Williams and others believed the church should continue to include social-political activity.

Other Social Services

Williams helped found the Atlanta Summit Leadership Council (ASLC). During the 1960s and 1970s the ASLC pressured the school board and city to end segregation emphasizing boycotts, sit-ins, marches, and similar tactics that relied on mass mobilization, nonviolent resistance, and civil disobedience.[6] Through the ASLC Williams led campaigns to expose the city of Atlanta and fought to expand mass transit into the predominantly African-American west side of the city.[6]

In 1966 Mayor Ivan Allen established the Community Relations Commission (CRC). Mayor Allen made Williams Vice Chair of the Atlanta branch.[7] The organization gave grassroots communities a mechanism to voice their concerns to city officials at the highest level.The organization worked for ending discriminatory hiring and promotions at City Hall. The CRC, under Williams conducted a study that proves the lack of minority hiring and the promotional practices of the city of Atlanta. This study was necessary in the CRC's argument in minority promotions.

Friendship Baptist Church

Friendship Baptist Church is one of the most prominent black baptist churches in Atlanta founded in 1865. In 1947 Williams became assistant pastor of Friendship Baptist Church. Later to become Senior Pastor Williams was one of the most activist-oriented pastors in Friendship’s history.[8]

Sermons

On February 19, 1969, Williams delivers a sermon on “A Challenge to Young Black College Students.” In this, he asserts that saying only Black teachers educate Black scholars is invalid but what he believes is needed is for good committed teachers regardless of color. In his sermons, he stressed that the black community is in sophisticated evasion cloaked in the fragile robe of good faith. He wanted his audience to steer away from moral double takes that is eroding away the moral integrity of the nation. Although, Williams was pro-civil disobedience, he, on occasion, lead sermons asserting that the system of society allows for the murder of a man in order to preserve social collectivities. Williams also warned the system is what allowed the enslavement, and exploitation of Blacks due to white despising Blacks. Williams loath the way the system had set up artificial barriers to deny other men their God given right.

After becoming pastor in 1954, Williams made vast improvements to the church such as building a low-rent apartment complex in 1969 and a parking lot that was paid off in 8 months. Williams continue to deliver sermons all across the country, however. Samuel Williams delivered a most- notable remarkable sermon on June 30, 1968, to an all white audience at All Saints Episcopal Church. There, he urged his audience to question what was their responsibility for justice, contending the power of deciding was in their field because they made up the mast majority.That is where he established his platform of schools should e a forum for the Christian's demand for justice.

Criticism and Legacy

Samuel Woodrow William's legacy was his contribution to the Civil Rights Movement and sermons at Friendship Baptist Church. He had, however, left an almost forgotten legacy of racial progress in Atlanta. Young men in his community critiqued him as dictatorial and an ineffective leader. Others accused him of failing to hold elections and of supporting a public housing controversy.Williams was also criticized for supporting white officials in the firing of Eliza Paschall, director of the CRC who was too “pro-black.”

Awards[1]

- Alpha kappa delta national honorary sociological fraternity (initiation certificate) - 1948

- Atlanta Morehouse club distinguished service award - 1959

- Phi Beta Sigma citizenship award (Chi Chapter) - 1959

- YMCA century club award - 1959

- Atlanta branch NAACP plague for presidency - 1964

- NAACP Meritorious award - 1969

- Community relations commission post humous - 1970

- YMCA men's club international ( Omega Chapter) - 1970

Death

Williams died in October 1970 after a surgical procedure.[9]

Further reading

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–1963. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

- Fort, Vincent. “The Atlanta Sit-In Movement, 1960–1961.” In Atlanta, Georgia, 1960–1961: Sit-Ins and Student Activism, ed. David Garrow. New York: Carlson Publishing, 1989.

- “Historic Summit Here Seeks End to All Remaining Racial Barriers: Closed Summit to Take All Day.” Atlanta Inquirer, October 19, 1963, pp. 1, 17.

- Lee, Barry E. “‘Bridge Over Troubled Waters’: Samuel W. Williams and the Desegregation of Atlanta.” Master’s thesis, Georgia State University, 1995.

- “Underdogs Have Defenders at City Hall.” Atlanta Journal, October 4, 1970, p. 2A.

References

- 1 2 3 "Samuel W. Williams papers, 1932-1974". findingaid.auctr.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wells, Rosa Marie (1975). ""Samuel Woodrow Williams, catalyst for black atlantans, 1946-1970"". digitalcommons.auctr.edu. ETD Collection for the AUC Robert W. Woodruff Library. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- 1 2 Jones, Edward. Candle in the Dark: A History of Morehouse College. Valley Forge, PA: The Judson Press, 1967.

- 1 2 “Rev. Williams Elected Acting NAACP Head.” Atlanta Daily World, April 3, 1970, p. 1.

- ↑ “Historic Summit Here Seeks End to All Remaining Racial Barriers: Closed Summit to Take All Day.” Atlanta Inquirer, October 19, 1963, pp. 1, 17.

- 1 2 3 Fort, Vincent. “The Atlanta Sit-In Movement, 1960–1961.” In Atlanta, Georgia, 1960–1961: Sit-Ins and Student Activism, ed. David Garrow. New York: Carlson Publishing, 1989.

- ↑ Allen, Ivan, Jr., with Paul Hemphill. Mayor: Notes on the Sixties. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971.

- ↑ Davis, John L. “Rev. Sam Williams Mourned by Thousands in Final Rites.” Atlanta Daily World, October 13, 1970, p. 1.

- ↑ Barry E. Lee. "Samuel Woodrow Williams (1912–1970)". The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. Retrieved January 20, 2017.