Samuel Cutler Ward

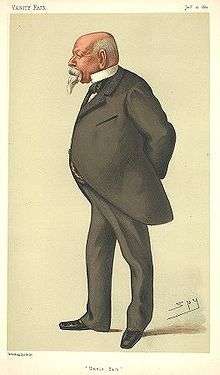

Ward as caricatured by Spy (Leslie Ward) in Vanity Fair, January 1880

Samuel Cutler "Sam" Ward IV (January 27, 1814 — May 19, 1884), was an American poet, politician, author, and gourmet, and in the years after the Civil War he was widely known as the "King of the Lobby." He combined delicious food, fine wines, and good conversation to create a new type of lobbying in Washington, DC—social lobbying—over which he reigned for more than a decade.

Early life

Sam was born in New York City into an old New England family and was the eldest of seven children. His father, Samuel Ward III, was a highly respected banker with the firm of Prime, Ward, and King. His grandfather, Col. Samuel Ward, Jr. (1756—1832), was a veteran of the Revolutionary War. Sam's mother, Julia Rush Cutler, was related to Francis Marion, the "Swamp Fox" of the American Revolution.

When Sam's mother died while he was a student at the Round Hill School in Northampton, Massachusetts, his father became morbidly obsessed with his children's moral, spiritual, and physical health. It wasn't until he was a student at Columbia College, where he joined the Philolexian Society and from which he graduated in 1831, that he began to learn about the wider world.

The more he learned, the less he wanted to become a banker. He convinced his father first to let him study in Europe. He stayed for four years, mastering several languages, enjoying high society, earning a doctorate degree from the University of Tübingen, and, in Heidelberg, meeting Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who became his friend for life. Sam literally dined out for decades on stories of his experiences during these years.

.jpg)

Back in New York, he tried to settle into the life of a young banker. In January 1838, he married Emily Astor, eldest daughter of businessman William Backhouse Astor, Sr. and Margaret Rebecca Armstrong. In November 1838, Emily gave birth to their daughter Margaret Astor Ward. She would marry John Winthrop Chanler, son of John White Chanler and Elizabeth Shirreff Winthrop, and have ten children, including William Astor Chanler, Sr., Lewis Stuyvesant Chanler, and Robert Winthrop Chanler.

Samuel Ward III died unexpectedly in November 1839. Next, Sam's brother Henry died suddenly of typhoid fever. In February 1841, Emily gave birth to a son, but within days both she and the newborn died. Sam was executor of his father's several-million-dollar estate, partner now in a prestigious banking firm, guardian of his three sisters, a widower, father of a toddler, and 27 years old.

In 1843, Sam married a beautiful fortune-hunter from New Orleans, Medora Grymes, who bore two sons in quick succession. Urged on by his wife, Sam began speculating on Wall Street. In September 1847, the financial world was stunned by news that Prime, Ward and Co. (King had wisely withdrawn) had collapsed.

Broke, Sam joined the '49ers rushing to California. He opened a store on the San Francisco waterfront; plowed his profits into real estate; claimed he made a quarter of a million dollars in three months; and lost it all when fire destroyed his wharves and warehouses. For a time he operated a ferry in the California wilderness; he alluded to mysterious schemes in Mexico and South America; and he bobbed up in New York a wealthy man again.

He plunged back into speculating and lost all of his money again, and with it went Medora's affection. This time he finagled a berth on a diplomatic mission to Paraguay. When he sailed home in 1859, he brought with him a secret agreement with the president of Paraguay to lobby on that country's behalf and headed to Washington, DC, to begin a new career.

Sam was a Democrat with many friends and family in the South. He also believed in gradual emancipation, which put him at odds with his sister, Julia Ward, who would later write "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," and her husband, Samuel Gridley Howe. But there was no question that he would remain loyal to the Union. He put his dinner table at the disposal of his neighbor Secretary of State William Henry Seward. His elegant meals, which had already begun to be noticed, provided the perfect cover for Northerners and Southerners looking for neutral ground. In the early days of the war, Sam also traveled through the Confederacy with British journalist William Howard Russell, secretly sending letters full of military details back to Seward for which he surely would have been hanged or shot if exposed.

In 1862, he told Seward he was wrong to think that the Confederacy would have rejoined the Union had war been averted: "I differ from you. I found among the leaders a malignant bitterness and contemptuous hatred of the North which rendered this lesson necessary. within two years they would have formed entangling free trade and free navigation treaties with Europe, and have become a military power hostile to us."[1]

Career

At the war's end, Sam's friends in high places, his savoir faire, his trove of anecdotes and recipes, and his talents for diplomacy augured well for his success in Washington, where the coals were hot and ready for an era of unprecedented growth and corruption that became known as "the Great Barbeque" or "The Gilded Age."

His entrée into the Johnson administration was Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch, who, faced with the colossal task of financial reconstruction, turned for help to Sam, who won for him a partial victory via cookery. Soon Sam was boasting to Julia that he was lobbying for insurance companies, telegraph companies, steamship lines, railroad lines, banking interests, mining interests, manufacturers, investors, and individuals with claims. Everyone, he crowed, wanted him. What they wanted was a seat at his famous table. His plan de campagne for lobbying often began with pâté de campagne, with a client footing the bill.

Sam took great care in composing the menu and guest list for his lobby dinners. If his client's interests were financial, members of the appropriate House and Senate committees received invitations. Mining and mineral rights? That was another group of players. He also orchestrated the talk around the table and used stories from his variegated life like condiments at his dinners.

The results? "Ambrosial nights," gushed one guest. "The climax of civilization," another enthused. But how did these delightful evenings serve his clients' ends? Subtly, and therein lies what set Sam Ward apart as a lobbyist. He claimed, and guests agreed, that he never talked directly about a "project" over dinner. Instead, he let a good food, wine, and company educate and convince, launch schemes or nip them in the bud. At these evenings new friendships developed, old ones were cemented, and Sam's list of men upon whom he could call lengthened.

This was the hallmark of what reporters labeled the "social lobby," and, by the late 1860s, Sam was hailed in newspapers across the country as its "King." And yet nowhere in this age of corruption and scandal—not in the press, in congressional testimony, or in his own letters or those of his clients—was there any hint that "the King" ever offered a bribe, engaged in blackmail, or used any other such methods to win his ends.

Later life

By the late 1870s, the "King of the Lobby" was slowing down. Although friends urged him to retire, the truth was that he couldn't. Sam was famous, but he was not rich. He lived well—very well indeed—but on other men's money. But then his luck changed once again. Years earlier, a wealthy Californian, James Keene, had been a poor, desperately ill teenager in the California gold fields and Sam had nursed him back to health. Keene never forgot his kindness. He manipulated railroad stock with his good "SAMaritan" in mind, and, when he came East in 1878, he gave Sam the profits—nearly $750,000.

With this dramatic change in his circumstances, the "King" abdicated his crown, decamped for New York, and naively backed unscrupulous strangers developing a grand new resort on Long Island. To no one's surprise but Sam's, the project failed and Sam's final fortune evaporated.

In order to evade creditors, Sam sailed for England. He bobbed up in London and was straightaway entertained by his many friends there and then moved on to Italy. During Lent in 1884, he became ill near Naples. On the morning of May 19, he dictated one last lighthearted letter and died.

Legacy

Within days of his passing, obituaries appeared in dozens of newspapers in the United States and England. The New York Times' obituary filled two entire columns. The New York Tribune correctly concluded that Sam Ward's "greatest achievement was establishing himself in Washington at the head of a profession which, from the lowest depths of disrepute, he raised almost to the dignity of a gentlemanly business....He never resorted to vulgar bribery; he excelled rather in composing the enmities and cementing the rickety friendships which play so large a part in political affairs, and he tempted men not with the purse, but with banquets, graced by vivacious company, and the conversation of wits and people of the world."

Sam's book of poetry, Lyrical Recreations, soon sank into obscurity. His hilarious anonymous magazine accounts of his stint in the gold fields were edited into a volume entitled Sam Ward in the Gold Rush in 1949. For years after his death, bar patrons ordered "Sam Wards," a drink he invented of cracked ice, a peel of lemon, and yellow Chartreuse. Restaurants carried Chicken Saute Sam Ward on their menus for decades. Locke-Ober in Boston served for years a dish called Mushrooms Sam Ward. He was immortalized by his nephew author Francis Marion Crawford as the delightful Mr. Bellingham in Dr. Claudius. And Sam's name has been kept alive by scholars speculating upon the identity of the anonymous author of "The Diary of a Public Man," published in 1879.

The social lobby that Sam Ward perfected also lives on. Although entertaining by lobbyists has been circumscribed by legislation, it endures because, as Sam understood, bringing people together over good food, wine, and conversation remains a fruitful way to conduct business. As Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. noted 100 years after Sam's death, ".....every close student of Washington knows half the essential business of government is still transacted in the evening.....where the sternest purpose lurks under the highest frivolity." Sam Ward's art was to guarantee that the guests who enjoyed his ambrosial nights never focused on the purpose that lurked beneath his perfectly cooked poisson.

References

- ↑ Nevins, Allan. The War for the Union, vol. 1, The Improvised War, 1861-1862 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1959), p. 53.

Bibliography

- Crawford, Francis Marion. Dr. Claudius. New York: Macmillan, 1883.

- Crofts, Daniel W. A Secession Crisis Enigma: William Henry Hurlbert and "The Diary of a Public Man." Baton Rouge: Louisiana State university Press, 2010.

- Elliott, Maud Howe. Uncle Sam Ward and His Circle. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1938.

- Jacob, Kathryn Allamong. King of the Lobby, the Life and Times of Sam Ward. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

- Thomas, Lately (pseudonym of Robert Steele). Sam Ward "King of the Lobby". Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1965.

- Ward, Samuel. Lyrical Recreations. New York: D. Appleton, Boston, 1865.

- Ward, Samuel. Sam Ward in the Gold Rush. (edited by Carvel Collins) Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1949.

Notes

External links

- Kathryn Allamong Jacob, King of the Lobby. The Life and Times of Sam Ward at Google Books

- Samuel Ward, Alias Carlos Lopez UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER LIBRARY BULLETIN Volume XII · Winter 1957 · Number 2