Occupation of German Samoa

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Occupation of Samoa – the takeover and subsequent administration of the Pacific colony of German Samoa – started in late August 1914 with landings by an expeditionary force from New Zealand called the "Samoa Expeditionary Force". The landings were unopposed and the New Zealanders took possession of Samoa for the New Zealand Government on behalf of King George V. The Samoa Expeditionary Force remained in the country until 1915 but its commander, Colonel Robert Logan, continued to administer Samoa on behalf of the New Zealand Government until 1919. The occupation of Samoa represented New Zealand's first military action in the First World War.

Background

Upon the outbreak of the First World War on 5 August 1914, the New Zealand Government authorised the raising of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) for service in the war. Mobilisation for the war had already begun, with preparations discreetly beginning a few days prior.[3] The day after the declaration of war, the British Government requested New Zealand seize the wireless station at German Samoa, a protectorate of Imperial Germany,[4] deeming it "a great and urgent Imperial service."[5]

Since the days of Richard Seddon, the Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1893 to 1906, the New Zealand Government had aspired to control Samoa. Even prior to the war, plans for the occupation of Samoa had been laid down by the Commandant of the New Zealand Military Forces, Major General Alexander Godley, who believed that this would be one likely usage of New Zealand's military in the event of an outbreak of hostilities.[6] The British request was immediately accepted and instructions issued to Godley to raise a composite force specifically tasked for this purpose.[5]

Prelude

What was to be known as the Samoa Expeditionary Force (SEF) was formed with volunteers drawn primarily from the Auckland and Wellington Military Districts. It included an infantry component, with three companies of infantry from the Auckland and Wellington Regiments, a battery of field guns, a section of engineers, companies of railway engineers and signallers, as well as personnel from the Royal Naval Reserve, Army Service Corps, a Field Ambulance section, as well as nurses and chaplains. There was also a detail from the New Zealand Post & Telegraph Company.[5]

Colonel Robert Logan, a member of the New Zealand Staff Corps and commander of the Auckland Military District, was appointed to command of the SEF.[7] At the time of its first formal parade on 11 August 1914,[8] the SEF consisted of over 1,400 personnel.[9]

The SEF departed New Zealand on 15 August in a convoy of troopships escorted by the New Zealand Naval Forces' HMS Philomel along with the Australian Navy's HMAS Pyramus and HMAS Psyche.[10] The escorting cruisers, all "P" class ships, were third-rate vessels deemed to be obsolete and no match for Vizeadmiral (Vice Admiral) Maximilian von Spee's East Asia Squadron with its armoured cruisers SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau.[Note 1] Therefore, it was arranged that the convoy would liaise at Fiji with the modern battlecruiser HMAS Australia and the French cruiser Montcalm. However, the day after departing New Zealand and unbeknownst to the New Zealand Government, the British Admiralty decided that the convoy would rendezvous with the modern escorts at Noumea in New Caledonia.[11]

Here the convoy was joined by HMAS Australia and the Montcalm, along with the cruiser HMAS Melbourne,[12] the entire expedition, now under the command of Rear Admiral George Patey,[13] went on to Fiji. Here several Legion-of-Frontiersmen and Samoan interpreters joined the SEF and it then sailed for Samoa on 27 August.[14]

Landing and occupation

The convoy arrived off Apia, on Samoa's main island of Upolu, on the morning of 29 August 1914.[15] At Apia, there were no defensive arrangements in place[1] with only around 100 local militia (known as Fita-fita) available.[2] Intelligence provided by the Australian authorities had already indicated that opposition was likely to be around 80 constables with a cadre of German officers along with a gunboat.[16][Note 2] However, the Germans could not count on the support of the Samoans to defend any attempts at a landing.[1] The Governor of German Samoa, Dr. Erich Schultz, had proceeded to the wireless station upon observing the approach of the convoy.[18]

While the Australian warships, together with the Montcalm, stood off from Apia, the Psyche proceeded into the town's harbour under a flag of truce. Transmissions from the wireless station were detected but these ceased following orders from Patey.[15] After an hour, a message from Schultz indicated that although Germany would not officially surrender the Samoan islands, there would be no resistance to a landing by the New Zealanders.[18] Upon receiving this news, the troopships began transferring the New Zealand soldiers into launches and shuttling them to shore.[19] Government buildings, including the post office and telegraph exchange, were seized by early evening and a party dispatched to the wireless station, in the hills several kilometres away. By the time the New Zealanders arrived, close to midnight, the German operators had sabotaged much of the equipment rendering it inoperative. Troops dispersed to camps and were allocated patrol areas.[20]

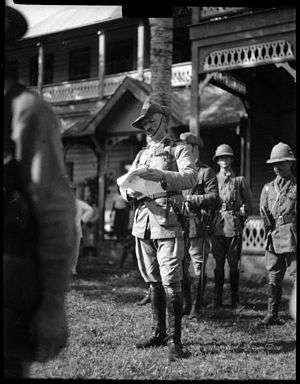

The following day, a ceremonial raising of the Union Jack took place in front of the courthouse, with Logan declaring the occupation of Samoa by the New Zealand Government on behalf of King George V.[21][Note 3] The damage to the wireless station prevented the success of the SEF being reported back to New Zealand until its repair on 2 September 1914.[20] In the meantime, stores from the troopships were unloaded and a railway line constructed from the Apia harbourside to the wireless station.[22]

Having completed their escort duties and with Samoa now secured, the Australian ships, plus the Montcalm, departed to join up with the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force, which was tasked with the capture of German New Guinea. Over the following days, the remaining P-class cruisers also left; two sailed for American Samoa and Tonga to inform the respective authorities of the occupation of Samoa. The Pyramus took five German prisoners, including Schultz, to Fiji.[23]

The German cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau hastened to Samoa after Admiral von Spee learned of the occupation. He arrived off Apia on 14 September 1914, three days after the departure of the last of the Allied cruisers and transports. The approach of the German ships was observed and the New Zealanders promptly manned their defences while many civilians, fearing exchanges of gunfire, made for the hills.[24] By this stage artillery has been set up on the beach but there was no exchange of gunfire. One historian, Ian McGibbon, wrote that this was likely due to von Spee's fears of damage to German property should he open fire.[11] Instead, von Spee steamed off and landed a small party further down the coast and learned from a German resident there the apparent strength of the occupation. Patrols dispatched to the area later interned the German resident.[25] According to the historian J. A. C. Gray, von Spee considered a landing by the forces under his control would only be of temporary advantage in an Allied-dominated sea[26] and so the German ships then made for Tahiti, a French possession. Here, not having to be concerned with the welfare of the local population and their property, von Spee would direct the bombardment of Papeete. He then rejoined the rest of his fleet and headed for South America.[11]

Aftermath

The SEF remained in Samoa until March 1915, at which time it began returning to New Zealand. A small relief force arrived in Apia on 3 April 1915 and the troopship that brought them to Samoa transported the last of the SEF back to New Zealand.[27] Logan remained and would continue to administer the country on behalf of the New Zealand Government until 1919. His term was controversial for he significantly mishandled the arrival of the influenza pandemic in November 1918, resulting in over 7,500 deaths.[28]

From 1920 until Samoan independence in 1962, New Zealand governed the islands as the Western Samoa Trust Territory, firstly as a League of Nations Class C Mandate, and then from 1945 as a United Nations Trust Territory.[29]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ There were concerns about the risk that the German squadron posed to the convoy, but McGibbon denies any basis for the assertion in the 1923 history, subsequently repeated by Michael King in his 2003 history of New Zealand, that the force narrowly escaped disaster, with the German cruisers sailing well to the north at the time rather than only 15 miles (25 km) distant.[11]

- ↑ Francis Fisher, the New Zealand Minister of Marine from 1912 to 1915, later recalled in a book published by Downie Stewart in 1937, that the New Zealand Government asked the British Colonial Secretary in London what defences there were in Samoa. He allegedly advised that it should consult Whitaker's Almanac but this was not supported by a search of papers in Archives New Zealand.[17]

- ↑ In the volume of the Official History of New Zealand's Effort in the Great War concerning the seizure of Samoa, it was claimed that Samoa was the first German territory captured in the war by British Imperial Forces. This is incorrect; the first seizure of a German colony had taken place four days earlier at Togoland, captured as part of the West Africa Campaign.[11]

- Citations

- 1 2 3 Boyd 1968, p. 148.

- 1 2 Längin 2005, p. 304.

- ↑ McGibbon 1991, p. 245.

- ↑ McGibbon 1991, p. 248.

- 1 2 3 Smith 1924, p. 14.

- ↑ McGibbon 1991, p. 240.

- ↑ Smith 1924, p. 15.

- ↑ Smith 1924, p. 22.

- ↑ Smith 1923, p. 23.

- ↑ Smith 1923, pp. 25–26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGibbon 2007, p. 65.

- ↑ Smith 1923, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Smith 1924, p. 47.

- ↑ Smith 1923, pp. 32–33.

- 1 2 Smith 1924, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ McGibbon 1991, p. 249.

- ↑ McGibbon 2007, p. 64.

- 1 2 Smith 1924, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Smith 1924, pp. 60–61.

- 1 2 Smith 1924, p. 63.

- ↑ Smith 1924, p. 64.

- ↑ Smith 1924, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Jose 1941, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Smith 1924, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Smith 1924, p. 95.

- ↑ Gray 1960, p. 185.

- ↑ Smith 1924, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Munro, D. (7 July 2005). "Logan, Robert 1863–1935". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Retrieved 5 January 2006.

- ↑ "Imperialism as a Vocation: Class C Mandates". Retrieved 27 November 2007.

References

- Boyd, Mary (October 1968). "The Military Administration of Western Samoa, 1914–1919". New Zealand Journal of History. 2 (2): 148–164. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- Gray, J.A.C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 606510006.

- Jose, Arthur W. (1941). The Royal Australian Navy, 1914–1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. IX. Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 559976970.

- Längin, B. G. (2005). Die deutschen Kolonien: Schauplätze und Schicksale 1888–1918 (in German). Hamburg, Germany: Mittler E.S. + Sohn. ISBN 978-3813208542.

- McGibbon, Ian (1991). The Path to Gallipoli: Defending New Zealand 1840–1915. New Zealand: GP Books. ISBN 0-477-00026-6.

- McGibbon, Ian (2007). "The Shaping of New Zealand's War Effort, August–October 1914". In Crawford, John; McGibbon, Ian. New Zealand's Great War: New Zealand, the Allies & the First World War. Auckland, New Zealand: Exisle Publishing. pp. 49–68. ISBN 978-0-908988-85-3.

- Smith, Sergeant S. J. (1923). "The Seizure and Occupation of Samoa". In Drew, Lieut. H. T. B. The War Effort of New Zealand. Official History of New Zealand's Effort in the Great War. Auckland, New Zealand: Whitcombe and Tombs Limited. OCLC 2778918.

- Smith, Stephen John (1924). The Samoa (N.Z.) Expeditionary Force 1914–1915. Wellington, New Zealand: Ferguson & Osborn. OCLC 8950668.