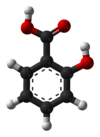

Salicylic acid

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Hydroxybenzoic acid[1] | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.648 | ||

| EC Number | 200-712-3 | ||

| KEGG | |||

| PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number | VO0525000 | ||

| UNII | |||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C7H6O3 | |||

| Molar mass | 138.12 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | colorless to white crystals | ||

| Odor | odorless | ||

| Density | 1.443 g/cm3 (20 °C)[2] | ||

| Melting point | 158.6 °C (317.5 °F; 431.8 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 200 °C (392 °F; 473 K) decomposes[3] 211 °C (412 °F; 484 K) at 20 mmHg[2] | ||

| sublimes at 76 °C[4] | |||

| 1.24 g/L (0 °C) 2.48 g/L (25 °C) 4.14 g/L (40 °C) 17.41 g/L (75 °C)[3] 77.79 g/L (100 °C)[5] | |||

| Solubility | soluble in ether, CCl4, benzene, propanol, acetone, ethanol, oil of turpentine, toluene | ||

| Solubility in benzene | 0.46 g/100 g (11.7 °C) 0.775 g/100 g (25 °C) 0.991 g/100 g (30.5 °C) 2.38 g/100 g (49.4 °C) 4.4 g/100 g (64.2 °C)[3][5] | ||

| Solubility in chloroform | 2.22 g/100 mL (25 °C)[5] 2.31 g/100 mL (30.5 °C)[3] | ||

| Solubility in methanol | 40.67 g/100 g (−3 °C) 62.48 g/100 g (21 °C)[3] | ||

| Solubility in olive oil | 2.43 g/100 g (23 °C)[3] | ||

| Solubility in acetone | 39.6 g/100 g (23 °C)[3] | ||

| log P | 2.26 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 10.93 mPa[4] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 1 = 2.97 (25 °C)[6] 2 = 13.82 (20 °C)[3] | ||

| UV-vis (λmax) | 210 nm, 234 nm, 303 nm (4 mg % in ethanol)[4] | ||

| -72.23·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Refractive index (nD) |

1.565 (20 °C)[2] | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH |

-589.9 kJ/mol | ||

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH |

3.025 MJ/mol[7] | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| A01AD05 (WHO) B01AC06 (WHO) D01AE12 (WHO) N02BA01 (WHO) S01BC08 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | MSDS | ||

| GHS pictograms |   [8] [8] | ||

| GHS signal word | Danger | ||

| H302, H318[8] | |||

| P280, P305+351+338[8] | |||

| Eye hazard | Severe irritation | ||

| Skin hazard | Mild irritation | ||

| NFPA 704 | |||

| Flash point | 157 °C (315 °F; 430 K) closed cup[4] | ||

| 540 °C (1,004 °F; 813 K)[4] | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

| LD50 (median dose) |

480 mg/kg (mice, oral) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

| Related compounds |

Methyl salicylate, Benzoic acid, Phenol, Aspirin, 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, Magnesium salicylate, Choline salicylate, Bismuth subsalicylate, Sulfosalicylic acid | ||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Salicylic acid (from Latin salix, willow tree) is a lipophilic monohydroxybenzoic acid, a type of phenolic acid, and a beta hydroxy acid (BHA). It has the formula C7H6O3. This colorless crystalline organic acid is widely used in organic synthesis and functions as a plant hormone. It is derived from the metabolism of salicin. In addition to serving as an important active metabolite of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), which acts in part as a prodrug to salicylic acid, it is probably best known for its use as a key ingredient in topical anti-acne products. The salts and esters of salicylic acid are known as salicylates. The medicinal part of the willow tree is the inner bark.

It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[9]

Uses

Medicine

Salicylic acid as a medication is used most commonly to help remove the outer layer of the skin.[10] As such it is used to treat warts, psoriasis, dandruff, acne, ringworm, and ichthyosis.[10][11]

As with other hydroxy acids, salicylic acid is a key ingredient in many skin-care products for the treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis, acne, psoriasis, calluses, corns, keratosis pilaris, acanthosis nigricans, ichthyosis and warts.[12]

Manufacturing

Salicylic acid is used in the production of other pharmaceuticals, including 4-aminosalicylic acid sandulpiride landetimide (via Salethamide).

Salicylic acid was one of the original starting materials for making acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) in 1897.[13]

Bismuth subsalicylate, a salt of bismuth and salicylic acid, is the active ingredient in stomach relief aids such as Pepto-Bismol, is the main ingredient of Kaopectate and "displays anti-inflammatory action (due to salicylic acid) and also acts as an antacid and mild antibiotic".[14]

Other derivatives include methyl salicylate used as a liniment to soothe joint and muscle pain and choline salicylate used topically to relieve the pain of mouth ulcers.

Chemistry

Salicylic acid has the formula C6H4(OH)COOH, where the OH group is ortho to the carboxyl group. It is also known as 2-hydroxybenzoic acid. It is poorly soluble in water (2 g/L at 20 °C).[15] Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid or ASA) can be prepared by the esterification of the phenolic hydroxyl group of salicylic acid with the acetyl group from acetic anhydride or acetyl chloride. Salicylic acid can also be prepared using the Kolbe-Schmitt reaction.

Other uses

Salicylic acid is used as a food preservative, a bactericidal and an antiseptic.[16]

Sodium salicylate is a useful phosphor in the vacuum ultraviolet, with nearly flat quantum efficiency for wavelengths between 10 and 100 nm.[17] It fluoresces in the blue at 420 nm. It is easily prepared on a clean surface by spraying a saturated solution of the salt in methanol followed by evaporation.

Safety

Burns

As a topical agent and as a beta-hydroxy acid (and unlike alpha-hydroxy acids), salicylic acid is capable of penetrating and breaking down fats and lipids, causing moderate chemical burns of the skin at very high concentrations. It may damage the lining of pores if the solvent is alcohol, acetone or an oil. Over-the-counter limits are set at 2% for topical preparations expected to be left on the face and 3% for those expected to be washed off, such as acne cleansers or shampoo. 17% and 27% salicylic acid, which is sold for wart removal, should not be applied to the face and should not be used for acne treatment. Even for wart removal, such a solution should be applied once or twice a day – more frequent use may lead to an increase in side-effects without an increase in efficacy.[18]

Hearing

When ingested, salicylic acid has a possible ototoxic effect by inhibiting prestin.[19] It can induce transient hearing loss in zinc-deficient rats. An injection of salicylic acid induced hearing loss, while an injection of zinc reversed the hearing loss. An injection of magnesium in the zinc-deficient rats did not reverse the induced hearing loss.

Pregnancy

No studies examine topical salicylic acid in pregnancy. Oral salicylic acid is not associated with an increase in malformations if used during the first trimester, but in late pregnancy has been associated with bleeding, especially intracranial bleeding.[20] The risks of aspirin late in pregnancy are probably not relevant for a topical exposure to salicylic acid, even late in the pregnancy, because of its low systemic levels. Topical salicylic acid is common in many over-the-counter dermatological agents and the lack of adverse reports suggests a low teratogenic potential.[21]

Overdose

Salicylic acid overdose can lead to salicylate intoxication, which often presents clinically in a state of metabolic acidosis with compensatory respiratory alkalosis. In patients presenting with an acute overdose, a 16% morbidity rate and a 1% mortality rate are observed.[22]

Allergy

Some people are hypersensitive to salicylic acid and related compounds.

Sun exposure

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends the use of sun protection when using skincare products containing salicylic acid (or any other BHA) on sun-exposed skin areas.[23]

Reye's syndrome

Data support an association between exposure to salicylic acid and Reye's Syndrome. The National Reye's Syndrome Foundation cautions against the use of these and other substances similar to aspirin on children and adolescents. Epidemiological research associated the development of Reye's Syndrome and the use of aspirin for treating the symptoms of influenza-like illnesses, chicken pox, colds, etc. The U.S. Surgeon General, the FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend that aspirin and combination products containing aspirin not be given to children under 19 years of age during episodes of fever-causing illnesses.[24]

Mechanism of action

Salicylic acid works through several different pathways. It produces its anti-inflammatory effects via suppressing the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme that is responsible for the production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as the prostaglandins. It does this not by direct inhibition of COX like most other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) but instead by suppression of the expression of the enzyme through a mechanism not yet understood.[25]

Salicylic acid activates adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and this action may play a role in the anticancer effects of the compound and its prodrugs aspirin and salsalate. The antidiabetic effects of salicylic acid are likely mediated by AMPK activation primarily through allosteric conformational change that increases levels of phosphorylation.[26]

Salicylic acid also uncouples oxidative phosphorylation, which leads to increased ADP:ATP and AMP:ATP ratios in the cell. As a consequence, salicylic acid may alter AMPK activity and work as an anti-diabetic by altering the energy status of the cell. AMPK knockout mice display an anti-diabetic effect, demonstrating at least one additional, yet unidentified action.[27]

Salicylic acid regulates c-Myc level at both transcriptional and post-transcription levels. Inhibition of c-Myc may be an important pathway by which aspirin exerts an anti-cancer effect, decreasing the occurrence of cancer in epithelial tissues.[28]

Plant hormone

Salicylic acid (SA) is a phenolic phytohormone and is found in plants with roles in plant growth and development, photosynthesis, transpiration, ion uptake and transport. SA also induces specific changes in leaf anatomy and chloroplast structure. SA is involved in endogenous signaling, mediating in plant defense against pathogens.[29] It plays a role in the resistance to pathogens by inducing the production of pathogenesis-related proteins.[30] It is involved in the systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in which a pathogenic attack on one part of the plant induces resistance in other parts. The signal can also move to nearby plants by salicylic acid being converted to the volatile ester, methyl salicylate.[31]

Production

Salicylic acid is biosynthesized from the amino acid phenylalanine. In Arabidopsis thaliana it can be synthesized via a phenylalanine-independent pathway.

Sodium salicylate is commercially prepared by treating sodium phenolate (the sodium salt of phenol) with carbon dioxide at high pressure (100 atm) and high temperature (390 K) – a method known as the Kolbe-Schmitt reaction. Acidification of the product with sulfuric acid gives salicylic acid:

It can also be prepared by the hydrolysis of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid)[32] or methyl salicylate (oil of wintergreen) with a strong acid or base.

History

Hippocrates, Galen, Pliny the Elder and others knew that willow bark could ease pain and reduce fevers.[33] It was used in Europe and China to treat these conditions.[34] This remedy is mentioned in texts from ancient Egypt, Sumer and Assyria.[35] The Cherokee and other Native Americans used an infusion of the bark for fever and other medicinal purposes.[36]

In 2014, archaeologists identified traces of salicylic acid on 7th century pottery fragments found in east central Colorado.[37] The Reverend Edward Stone, a vicar from Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, England, noted in 1763 that the bark of the willow was effective in reducing a fever.[38]

The active extract of the bark, called salicin, after the Latin name for the white willow (Salix alba), was isolated and named by the German chemist Johann Andreas Buchner in 1828.[39] A larger amount of the substance was isolated in 1829 by Henri Leroux, a French pharmacist.[40] Raffaele Piria, an Italian chemist, was able to convert the substance into a sugar and a second component, which on oxidation becomes salicylic acid.[41][42]

Salicylic acid was also isolated from the herb meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria, formerly classified as Spiraea ulmaria) by German researchers in 1839.[43] While their extract was somewhat effective, it also caused digestive problems such as gastric irritation, bleeding, diarrhea and even death when consumed in high doses.

Dietary sources

Salicylic acid occurs in plants as free salicylic acid and its carboxylated esters and phenolic glycosides. Several studies suggest that humans metabolize salicylic acid in measurable quantities from these plants;[44] one study found that vegetarians not taking aspirin had urinary levels of salicylic acid roughly 5% those of patients taking 75 mg of aspirin per day, while the non-vegetarians had levels roughly one-third that of vegetarians.[45] Dietary sources of salicylic acid and their interaction with drugs such as aspirin have not been well studied.[46] Ongoing clinical studies of patients with aspirin-induced asthma have shown some benefits of a diet[47] low in salicylic acid.[48] Dietary salicylic acid may be partially responsible for the health benefits of a plant-based diet.[49]

Studies on the salicylic content of foods are sparse and have produced distinctly different results, creating controversy.[44] Possible causes for the discrepancies include uncontrolled and often unreported factors such as cultivation area, crop species, and harvest methods, as well as inherent issues with the studies such as poor extraction and measurement procedures and limited or low-accuracy equipment. A recent study using best practice measurement methodology significantly reduced intra-sample measurement variability but has not yet been replicated or extended.[44]

Some results have been consistently reported. Meat, poultry, fish, eggs, oils, dairy products, sugar, cereals, and flour all have little to no salicylates.[50] Measurable levels of salicylic acid have been found in fruits, vegetables, herbs, spices, nuts, and teas.[44]

See also

References

- ↑ Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001.

- 1 2 3 Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 3.306. ISBN 1439855110.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Salicylic acid".

- 1 2 3 4 5 CID 338 from PubChem

- 1 2 3 Atherton Seidell; William F. Linke (1952). Solubilities of Inorganic and Organic Compounds: A Compilation of Solubility Data from the Periodical Literature. Supplement. Van Nostrand.

- ↑ Salicyclic acid. Drugbank.ca. Retrieved on 2012-06-03.

- ↑ "Salicylic acid".

- 1 2 3 Sigma-Aldrich Co., Salicylic acid. Retrieved on 2014-05-23.

- ↑ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- 1 2 "Salicylic acid topical medical facts from Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ WHO Model Formulary 2008 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. p. 310. ISBN 9789241547659. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ Madan RK; Levitt J (April 2014). "A review of toxicity from topical salicylic acid preparations". J Am Acad Dermatol. 70 (4): 788–92. PMID 24472429. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.005.

- ↑ Schrör, Karsten (2016). Acetylsalicylic Acid (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 9-10. ISBN 9783527685028.

- ↑ "Bismuth subsalicylate". PubChem. United States National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Salicilyc acid". inchem.org. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ↑ "Definition of Salicylic acid". MedicineNet.com.

- ↑ Samson, James (1976). Techniques of Vacuum Ultraviolet Spectroscopy. Wiley, .

- ↑ salicylic acid 17 % Topical Liquid. Kaiser Permanente Drug Encyclopedia. Accessed 28 Sept 2011.

- ↑ Wecker, H.; Laubert, A. (2004). "Reversible hearing loss in acute salicylate intoxication". HNO (in German). 52 (4): 347–51. PMID 15143764. doi:10.1007/s00106-004-1065-5.

- ↑ Rumack, CM; Guggenheim, MA; Rumack, BH; Peterson, RG; Johnson, ML; Braithwaite, WR (1981). "Neonatal intracranial hemorrhage and maternal use of aspirin". Obstetrics and gynecology. 58 (5 Suppl): 52S–6S. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 7312229.

- ↑ Acne and Pregnancy. Fetal-exposure.org. Retrieved on 2012-06-03.

- ↑ Salicylate Toxicity at eMedicine

- ↑ "Beta Hydroxy Acids in Cosmetics". Archived from the original on 2007-12-21. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Aspirin / Salicylates and Reye's Syndrome". reyessyndrome.org. Retrieved 2009-05-22.

- ↑ "Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Aspirin – It's All About Salicylic Acid". American Chemical Society.

- ↑ Hawley, S. A.; Fullerton, M. D.; Ross, F. A.; Schertzer, J. D.; Chevtzoff, C.; Walker, K. J.; Peggie, M. W.; Zibrova, D.; et al. (2012). "The Ancient Drug Salicylate Directly Activates AMP-Activated Protein Kinase". Science. 336 (6083): 918–22. PMC 3399766

. PMID 22517326. doi:10.1126/science.1215327.

. PMID 22517326. doi:10.1126/science.1215327. - ↑ Raffensperger, Lisa (2012-04-19). "Clues to aspirin's anti-cancer effects revealed". New Scientist

- ↑ Ai, G; Dachineni, R; Muley, P; Tummala, H; Bhat, GJ (2016). "Aspirin and salicylic acid decrease c-Myc expression in cancer cells: a potential role in chemoprevention". Tumour Biol. 37: 1727–38. PMID 26314861. doi:10.1007/s13277-015-3959-0.

- ↑ Hayat, S. & Ahmad, A. (2007). Salicylic acid – A Plant Hormone. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-5183-2.

- ↑ Van Huijsduijnen, R. A. M. H.; Alblas, S. W.; De Rijk, R. H.; Bol, J. F. (1986). "Induction by Salicylic Acid of Pathogenesis-related Proteins and Resistance to Alfalfa Mosaic Virus Infection in Various Plant Species". Journal of General Virology. 67 (10): 2135–2143. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-67-10-2135.

- ↑ Taiz, L. and Zeiger, Eduardo (2002) Plant Physiology, 3rd Edition, Sinauer Associates, p. 306, ISBN 0878938230.

- ↑ "Hydrolysis of ASA to SA". Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Norn, S.; Permin, H.; Kruse, P. R.; Kruse, E. (2009). "[From willow bark to acetylsalicylic acid]". Dansk Medicinhistorisk Årbog (in Danish). 37: 79–98. PMID 20509453.

- ↑ "Willow bark". University of Maryland Medical Center. University of Maryland. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Seaman, David R. (19 July 2011). "White Willow Bark: The Oldest New Natural Anti-Inflammatory/Analgesic Agent". The American Chiropractor. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Hemel, Paul B. and Chiltoskey, Mary U. Cherokee Plants and Their Uses – A 400 Year History, Sylva, NC: Herald Publishing Co. (1975); cited in Dan Moerman, A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. A search of this database for "salix AND medicine" finds 63 entries.

- ↑ "1,300-Year-Old Pottery Found in Colorado Contains Ancient ‘Natural Aspirin’".

- ↑ Stone, Edmund (1763). "An Account of the Success of the Bark of the Willow in the Cure of Agues". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 53: 195–200. doi:10.1098/rstl.1763.0033.

- ↑ Buchner, A. (1828). "Ueber das Rigatellische Fiebermittel und über eine in der Weidenrinde entdeckte alcaloidische Substanz (On Rigatelli's antipyretic [i.e., anti-fever drug] and on an alkaloid substance discovered in willow bark)". Repertorium für die pharmacie... Bei J. L. Schrag. pp. 405–.

Noch ist es mir aber nicht geglückt, den bittern Bestandtheil der Weide, den ich Salicin nennen will, ganz frei von allem Färbestoff darzustellen." (I have still not succeeded in preparing the bitter component of willow, which I will name salicin, completely free from colored matter

- ↑ See:

- Leroux, H. (1830). "Mémoire relatif à l'analyse de l'écorce de saule et à la découverte d'un principe immédiat propre à remplacer le sulfate de quinine"] (Memoir concerning the analysis of willow bark and the discovery of a substance immediately likely to replace quinine sulfate)". Journal de chimie médicale, de pharmacie et de toxicologie. Chez Béchet jeune. 6: 340–342.

- A report on Leroux's presentation to the French Academy of Sciences also appeared in: Mémoires de l'Académie des sciences de l'Institut de France. Institut de France. 1838. pp. 20–.

- ↑ Piria (1838) "Sur de neuveaux produits extraits de la salicine" (On new products extracted from salicine), Comptes rendus … 6: 620–624. On page 622, Piria mentions "Hydrure de salicyle" (hydrogen salicylate, i.e., salicylic acid).

- ↑ Jeffreys, Diarmuid (2005). Aspirin: the remarkable story of a wonder drug. New York: Bloomsbury. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-1-58234-600-7.

- ↑ Löwig, C.; Weidmann, S. (1839). "III. Untersuchungen mit dem destillierten Wasser der Blüthen von Spiraea Ulmaria (III. Investigations of the water distilled from the blossoms of Spiraea ulmaria). Löwig and Weidman called salicylic acid Spiräasaure (spiraea acid)". Annalen der Physik und Chemie; Beiträge zur organischen Chemie (Contributions to organic chemistry). J.A. Barth. (46): 57–83.

- 1 2 3 4 Malakar, Sreepurna; Gibson, Peter R.; Barrett, Jacqueline S.; Muir, Jane G. (1 April 2017). "Naturally occurring dietary salicylates: A closer look at common Australian foods". Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 57: 31–39. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2016.12.008.

- ↑ Lawrence, J R; Peter, R; Baxter, G J; Robson, J; Graham, A B; Paterson, J R (28 May 2017). "Urinary excretion of salicyluric and salicylic acids by non-vegetarians, vegetarians, and patients taking low dose aspirin". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 56 (9): 651–653. ISSN 0021-9746.

- ↑ Race, Sharla. "Salicylate in Food". The Salicylate Handbook: Your Guide to Understanding Salicylate Sensitivity. Sharla Race. ISBN 9781907119040.

- ↑ "Food Guide". Salicylate Sensitivity.

- ↑ Sommer, Doron D.; Rotenberg, Brian W.; Sowerby, Leigh J.; Lee, John M.; Janjua, Arif; Witterick, Ian J.; Monteiro, Eric; Gupta, Michael K.; Au, Michael; Nayan, Smriti (April 2016). "A novel treatment adjunct for aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease: the low-salicylate diet: a multicenter randomized control crossover trial". International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. 6 (4): 385–391. doi:10.1002/alr.21678.

- ↑ Greger, Michael. "Inflammation, Diet, and “Vitamin S” | NutritionFacts.org". NutritionFacts.org.

- ↑ "Salicylates in foods" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-05-09.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salicylic acid. |

- Salicylic acid MS Spectrum

- Safety MSDS data

- International Chemical Safety Cards | CDC/NIOSH

- English Translation of Hermann Kolbe's seminal 1860 German article in Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. English title: 'On the syntheses of salicylic acid'; German title "Ueber Synthese der Salicylsäure".