Sakurai's Bell inequality

The intention of a Bell inequality is to serve as a test of local realism or local hidden variable theories as against quantum mechanics, applying Bell's theorem, which shows them to be incompatible. Not all the Bell's inequalities that appear in the literature are in fact fit for this purpose. The one discussed here holds only for a very limited class of local hidden variable theories and has never been used in practical experiments. It is, however, discussed by John Bell in his "Bertlmann's socks" paper (Bell, 1981), where it is referred to as the "Wigner–d'Espagnat inequality" (d'Espagnat, 1979; Wigner, 1970). It is also variously attributed to Bohm (1951?) and Belinfante (1973).

Note that the inequality is not really applicable either to electrons or photons, since it builds in no probabilistic properties in the measurement process. Much more realistic hidden variable theories can be devised, modelling spin (or polarisation, in optical Bell tests) as a vector and allowing for the fact that not all emitted particles will be detected.

Derivation of the inequality

The approach of Sakurai (1994) is followed.

Pick three arbitrary directions a, b, and c in which Alice and Bob can measure the spins of each electron they receive. We assume three hidden variables on each electron, for the three direction spins. We furthermore assume that these hidden variables are assigned to each electron pair in a consistent way at the time they are emitted from the source, and don't change afterwards. We do not assume anything about the probabilities of the various hidden variable values.

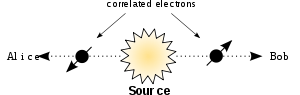

Alice and Bob are two spatially separated observers. Between them is an apparatus that continuously produces pairs of electrons. One electron in each pair is sent toward Alice, and the other toward Bob. The setup is shown in the diagram.

(This is just a thought-experiment, remember. Real experiments on pairs of electrons are not feasible and most "Bell test experiments" have instead been based on either the polarisation direction or the frequency and phase of light as individual particles called photons.)

The electron pairs are specially prepared so that if both observers measure the spin of their electron along the same axis, then they will always get opposite results. For example, suppose Alice and Bob both measure the z-component of the spins that they receive. According to quantum mechanics, each of Alice's measurements will give either the value +1/2 or −1/2, with equal probability. For each result of +1/2 obtained by Alice, Bob's result will inevitably be −1/2, and vice versa.

Mathematically, the state of each two-electron composite system can be described by the state vector

- (1)

Each ket is labelled by the direction in which the electron spin points. The above state is known as a spin singlet. The z-component of the spin corresponds to the operator (1/2)σz, where σz is the third Pauli matrix.

It is possible to explain this phenomenon without resorting to quantum mechanics. Suppose our electron-producing apparatus assigns a parameter, known as a hidden variable, to each electron. It labels one electron "spin +1/2", and the other "spin −1/2". The choice of which of the two electrons to send to Alice is decided by some classical random process. Thus, whenever Alice measures the z-component spin and finds that it is +1/2, Bob will measure −1/2, simply because that is the label assigned to his electron. This reproduces the effects of quantum mechanics, while preserving the locality principle.

The appeal of the hidden variables explanation dims if we notice that Alice and Bob are not restricted to measuring the z-component of the spin. Instead, they can measure the component along any arbitrary direction, and the result of each measurement is always either +1/2 or −1/2. Therefore, each electron must have an infinite number of hidden variables, one for each measurement that could possibly be performed.

This is ugly, but not in itself fatal. However, Bell showed that by choosing just three directions in which to perform measurements, Alice and Bob can differentiate hidden variables from quantum mechanics.

| Alice | Bob | Probability |

|---|---|---|

| a b c | a b c | |

| + + + | − − − | P1 |

| + + − | − − + | P2 |

| + − + | − + − | P3 |

| + − − | − + + | P4 |

| − + + | + − − | P5 |

| − + − | + − + | P6 |

| − − + | + + − | P7 |

| − − − | + + + | P8 |

Each row in the table describes one type of electron pair, with their respective hidden variable values and their probabilities P. Suppose Alice measures the spin in the a direction and Bob measures it in the b direction. Denote the probability that Alice obtains +1/2 and Bob obtains +1/2 by

- (2) P(a+, b+) = P3 + P4

Similarly, if Alice measures spin in a direction and Bob measures in c direction, the probability that both obtain +1/2 is

- (3) P(a+, c+) = P2 + P4

Finally, if Alice measures spin in c direction and Bob measures in b direction, the probability that both obtain the value +1/2 is

- (4) P(c+, b+) = P3 + P7

The probabilities P are always non-negative, and therefore:

- (5) P3 + P4 ≤ P3 + P4 + P2 + P7

This gives

- (6) P(a+, b+) ≤ P(a+, c+) + P(c+, b+)

which is a (rather trivial) Bell inequality. It must be satisfied by any hidden variable theory if it is to match the quantum-mechanical prediction in circumstances in which every single particle is detected.

The quantum-mechanical prediction for the above setup is:

- (7) P(a+, b+) = 1/2 (sin(a − b)/2)2.

Bell's application of the inequality

Bell[1] discusses the application of the inequality to thought-experiment involving the spin of electrons and Stern–Gerlach magnets.

The inequality would require

- (8) 1/2 (sin 45°)2 ≤ 1/2 (sin 22.5°)2 + 1/2 (sin 22.5°)2

or

- (9) 0.2500 ≤ 0.1464

which is not true, proving his theorem. The prediction of quantum mechanics does indeed conflict with that of local realism.

Note that the Uncertainty principle implies that the probabilities P1-P8 are ill-defined because there is no way of simultaneously obtaining the corresponding outcomes.

In real experiments, given that not all particles are detected, the above test could (as with the practical version of the CHSH Bell test) not legitimately be used unless the assumption is made that the detected particles are a fair sample of those emitted. The failure of this assumption results in the best known "loophole". When there are some non-detections, hidden variable theories exist that, like quantum mechanics, predict violation of the inequality. When the non-detections are indeed the correct explanation for experimental results, this would mean that quantum mechanics is in principle wrong in its predicting of the measurement outcomes, but accidentily exactly correct, when taking into account the detector efficiencies.

References

- ↑ pages 145–150 of his "Bertlmann's socks" article

- Belinfante: A Survey of Hidden-Variables Theories (Oxford: Pergamon), 1973

- Bell, J. S.: "Bertlmann's socks and the nature of reality", Journal de Physique, Colloque C2, suppl. au numero 3, Tome 42 (1981) pp C2 41–61, reproduced as Ch. 16 of Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics, Cambridge University Press 1987

- Bohm, D.: Quantum Mechanics, Prentice–Hall 1951

- d'Espagnat, B.: Scientific American, p158, November 1979

- Sakurai, J.J.: Modern Quantum Mechanics. Addison–Wesley, USA 1994, pp. 174–187, 223–232

- Wigner, E. P.: Americal Journal of Physics 38, 1005 (1970)