Scythian languages

| Scythian | |

|---|---|

|

Ptolemy's Scythia | |

| Native to | Sarmatia, Scythia, Sistan, Scythia Minor, Alania |

| Region | Central Asia, Eastern Europe |

| Ethnicity | Scythians, Sarmatians, and Alans |

| Era | Classical antiquity, late antiquity |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

Variously:xsc – Scythianxln – Alanianoos – Old Ossetian |

xsc Scythian | |

xln Alanian | |

oos Old Ossetian | |

| Glottolog |

oldo1234 Old Ossetic[1] |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East-Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East-Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

The Scythian languages (/ˈsɪθiən/ or /ˈsɪðiən/) are a group of Eastern Iranian languages of the classical and late antiquity (Middle Iranian) period, spoken in a vast region of Eurasia named Scythia. Except for modern Ossetian, which descends from the Alanian variety, these languages are all considered to be extinct. Modern Eastern Iranian languages such as Wakhi, however, are related to the eastern Scytho-Khotanese dialects attested from the kingdoms of Khotan and Tumshuq in the ancient Tarim Basin, in present-day southern Xinjiang, China.

The location and extent of Scythia varied by time, but generally it encompassed the part of Eastern Europe east of the Vistula river and much of Central Asia up to the Tarim Basin. The dominant ethnic groups among the Scythians were nomadic pastoralists of Central Asia and the Pontic-Caspian steppe. Fragments of their speech known from inscriptions and words quoted in ancient authors as well as analysis of their names indicate that it was an Indo-European language, more specifically from the Iranian group of Indo-Iranian languages. Alexander Lubotsky summarizes the known linguistic landscape as follows:[2]

Unfortunately, we know next to nothing about the Scythian of that period [Old Iranian] – we have only a couple of personal and tribal names in Greek and Persian sources at our disposal – and cannot even determine with any degree of certainty whether it was a single language.

Classification

The vast majority of Scythological scholars agree in considering the Scythian languages (and Ossetian) as a part of the Eastern Iranian group of languages. This Iranian hypothesis relies principally on the fact that the Greek inscriptions of the Northern Black Sea Coast contain several hundreds of Sarmatian names showing a close affinity to the Ossetian language. The classification of the Iranian languages is in general not however fully resolved, and the Eastern Iranian languages are not shown to form an actual genetic subgroup.[3][4]

Some scholars detect a division of Scythian into two dialects: a western, more conservative dialect, and an eastern, more innovative one.[5] The Scythian languages may have formed a dialect continuum:

- Alanian languages or Scytho-Sarmatian in the west: were spoken by people originally of Iranian stock[6] from the 8th and 7th century BC onwards in the area of Ukraine, Southern Russia and Kazakhstan. Modern Ossetian survives as a continuation of the language family possibly represented by Scytho-Sarmatian inscriptions, although the Scytho-Sarmatian language family "does not simply represent the same [Ossetian] language" at an earlier date.[7]

- Saka languages or Scytho-Khotanese in the east: spoken in the first century in the Kingdom of Khotan (located in present-day Xinjiang, China), and including the Khotanese of Khotan and Tumshuqese of Tumshuq.[8]

Other East Iranian languages related to the Scythian are Chorasmian and Sogdian.[9]

History

Early Eastern Iranians originated in the Yaz culture (ca. 1500–1100 BC) in Central Asia. The Scythians migrated from Central Asia toward Eastern Europe in the 8th and 7th century BC,[10] occupying today's Southern Russia and Ukraine and the Carpathian Basin and parts of Moldova and Dobruja. They disappeared from history after the Hunnish invasion of Europe in the 5th century AD, and Turkic (Avar, Batsange, etc.) and Slavic peoples probably assimilated most people speaking Scythian. However, in the Caucasus, the Ossetian language belonging to the Scythian linguistic continuum remains in use today, while in Central Asia, some languages belonging to Eastern Iranian group are still spoken, namely Pashto, Pamir languages and Yaghnobi.

Corpus

Inscriptions

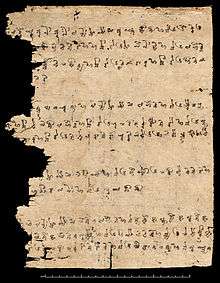

Some scholars ascribe certain inscribed objects found in the Carpathian Basin and in Central Asia to the Scythians, but the interpretation of these inscriptions remains disputed (given that nobody has definitively identified the alphabet or translated the content).

An inscription from Saqqez written in the Hieroglyphic Hittite script may represent Scythian:[11]

| Transliteration: | par-tì-ta₅-wa₅ ki-ś₃-a₄-á KUR-u-pa-ti QU-wa-a₅ | i₅-pa-ś₂-a-m₂ |

| Transcription: | Partitava xšaya DAHYUupati xva|ipašyam |

| Translation: | King Partitavas, the masters of the land property." |

King Partitava equates to the Scythian king called Prototyēs in Herodotus (1.103) and known as Par-ta-tu-a in the Assyrian sources. ("Partatua of Sakasene" married the daughter of Esarhaddon c. 675 BC)

The Issyk inscription, found in a Scythian kurgan dating approximately to the 4th century BC, remains undeciphered, but some authorities assume that it represents Scythian.

Personal names

The primary sources for Scythian words remain the Scythian toponyms, tribal names, and numerous personal names in the ancient Greek texts and in the Greek inscriptions found in the Greek colonies on the Northern Black Sea Coast. These names suggest that the Scythian language had close similarities to modern Ossetian.

Some scholars believe that many toponyms and hydronyms of the Russian and Ukrainian steppe have Scythian links. For example, Vasmer associates the name of the river Don with an assumed/reconstructed unattested Scythian word *dānu "water, river", and with Avestan dānu-, Pashto dand and Ossetian don.[12] The river names Don, Donets, Dnieper, Danube, Dniester and lake Donuzlav (the deepest one in Crimea) may also belong with the same word-group.[13]

Herodotus' Scythian etymologies

The Greek historian Herodotus provides another source of Scythian; he reports that the Scythians called the Amazons Oiorpata, and explains the name as a compound of oior, meaning "man", and pata, meaning "to kill" (Hist. 4,110).

- Most scholars associate oior "man" with Avestan vīra- "man, hero", Sanskrit vīra-, Latin vir (gen. virī) "man, hero, husband",[14] PIE *u̯iHro-. Various explanations account for pata "kill":

- Alternatively, one scholar suggests Iranian aiwa- "one" + warah- "breast",[18] the Amazons believed to have removed a breast to aid drawing a bow, according to some ancient folklorists, and as reflected in Greek folk-etymology: a- (privative) + mazos, "without breast".

Elsewhere Herodotus explains the name of the mythical one-eyed tribe Arimaspoi as a compound of the Scythian words arima, meaning "one", and spu, meaning "eye" (Hist. 4,27).

- Some scholars connect arima "one" with Ossetian ærmæst "only", Avestic airime "quiet", Greek erēmos "empty", PIE *h₁(e)rh₁mo-?, and spu "eye" with Avestic spas- "foretell", Sanskrit spaś-, PIE *speḱ- "see".[19]

- However, Iranian usually expresses "one" and "eye" with words like aiwa- and čašman- (Ossetian īw and cæst).

- Other scholars reject Herodotus' etymology and derive the ethnonym Arimaspoi from Iranian aspa- "horse" instead.[20]

- Or the first part of the name may reflect something like Iranian raiwant- "rich", cf. Ossetian riwæ "rich".[21]

Herodotus' Scythian theonyms

Herodotus also gives a list of Scythian theonyms (Hist. 4.59):

- Tabiti = Hestia. Perhaps related to Sanskrit Tapatī, a heroine in the Mahābhārata, literally "the burning (one)".[22]

- Papaios = Zeus. Either "father" (Herodotus) or "protector", Avestan, Sanskrit pā- "protect", PIE *peh₃-.[23]

- Api = Gaia. Either "mother"[24] or "water", Avestan, Sanskrit āp-, PIE Hep-[25]

- Goitosyros or Oitosyros = Apollo. Perhaps Avestan gaēθa- "animal" + sūra- "rich".[26]

- Argimpasa or Artimpasa = Aphrodite Urania. To Ossetic art and Pashto or, "fire", Avestan āθra-.[27]

- Thagimasadas = Poseidon.

Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Elder's Natural History (AD 77–79) derives the name of the Caucasus from the Scythian kroy-khasis = ice-shining, white with snow (cf. Greek cryos = ice-cold).

Alanian

The Alanian language as spoken by the Alans from about the 5th to the 11th centuries AD formed a dialect directly descended from the earlier Scytho-Sarmatian languages, and forming in its turn the ancestor of the Ossetian language. Byzantine Greek authors recorded only a few fragments of this language.[28]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Old Ossetic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Lubotsky 2002, p. 190.

- ↑ Compare L. Zgusta, Die griechischen Personennamen griechischer Städte der nördlichen Schwarzmeerküste [The Greek personal names of the Greek cities of the northern Black Sea coast], 1955.

- ↑ Witzel, Michael (2001). "Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 7 (3): 1–115.

- ↑ E.g. Harmatta 1970.

- ↑ Scythian, member of a nomadic people originally of Iranian stock who migrated from Central Asia to southern Russia in the 8th and 7th centuries BC – Encyclopædia Britannica 15th edition – Micropaedia on "Scythian"

- ↑ The languages of the Scytho-Sarmatian inscription may represent dialects of a language family of which Modern Ossetian is a continuation, but does not simply represent the same language at an earlier time – Encyclopædia Britannica 15th edition – Macropedia on Languages of the World

- ↑ Schmitt, Rüdiger (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Reichert, 1989.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica 15th edition – Macropedia on Languages of the World

- ↑ Scythian, member of a nomadic people originally of Iranian people who migrated from Central Asia to southern Russia in the 8th and 7th centuries BC—The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition—Micropædia on "Scythian", 10:576

- ↑ Text and translation in J. Harmatta, "Herodotus, historian of the Cimmerians and the Scythians", in: Hérodote et les peuples non grecs, Vandœuvres-Genève 1990, pp. 115–130.

- ↑ M. Vasmer, Untersuchungen über die ältesten Wohnsitze der Slaven. Die Iranier in Südrußland, Leipzig 1923, 74.

- ↑ P. Kretschmer, "Zum Balkan-Skythischen", Glotta 24 (1935), 1–56, here: 7ff.

- ↑ http://latindictionary.wikidot.com/noun:vir

- ↑ Vasmer, Die Iranier in Südrußland, 1923, 15.

- ↑ V.I. Abaev, Osetinskij jazyk i fol’klor, Moscow / Leningrad 1949, vol. 1, 172, 176, 188.

- ↑ L. Zgusta, "Skythisch οἰόρπατα «ἀνδροκτόνοι»", Annali dell’Istituto Universario Orientale di Napoli 1 (1959) pp. 151–156.

- ↑ Hinge 2005, pp. 94–98

- ↑ J. Marquart, Untersuchungen zur Geschichte von Eran, Göttingen 1905, 90–92; Vasmer, Die Iranier in Südrußland, 1923, 12; H.H. Schaeder, Iranica. I: Das Auge des Königs, Berlin 1934, 16–19.

- ↑ W. Tomaschek, "Kritik der ältesten Nachrichten über den skythischen Norden", Sitzungsberichte der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 116 (1888), 715–780, here: 761; K. Müllenhoff, Deutsche Altertumskunde, Berlin 1893, vol. 3, 305–306; R. Grousset, L’empire des steppes, Paris 1941, 37 n. 3; I. Lebedensky, Les Scythes. La civilisation des steppes (VIIe-IIIe siècles av. J.-C.), Paris 2001, 93.

- ↑ Hinge 2005, pp. 89–94

- ↑ W. Brandenstein, "Die Abstammungssagen der Skythen", Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 52 (1953) 183–211, here: 191; Ė.A. Grantovskij & D.S. Raevskij, "Ob iranojazyčnom i «indoarijskom» naselenii Severnogo Pričernomor’ja v antičnuju ėpochu", in: Ėtnogenez narodov Balkan i Severnogo Pričernomor’ja. Lingvistika, istorija, archeologija, Moscow 1984, 47–66, here: 53–55; G. Dumézil, Romans de Scythie et d’alentour, Paris 1978, 125–145; Dumézil offers a different interpretation in La courtisane et les seigneurs colorés. Esquisses de mythologie, Paris 1983, 124–125.

- ↑ Vasmer, Die Iranier in Südrußland, 1923, 15; L. Zgusta, "Zwei skythische Götternamen", Archiv orientální 21 (1953), pp. 270–271; Grantovskij and Raevskij, in: Ėtnogenez narodov Balkan i Severnogo Pričernomor’ja, 1984, 54.

- ↑ L. Zgusta, "Zwei skythische Götternamen", Archiv orientální 21 (1953), pp. 270–271.

- ↑ Vasmer, Die Iranier in Südrußland, 1923, 11; Brandenstein, Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 52 (1953) 190–191; Grantovskij and Raevskij, in: Ėtnogenez narodov Balkan i Severnogo Pričernomor’ja, 1984, 54.

- ↑ Vasmer, Die Iranier in Südrußland, 1923, 13; other interpretations in Dumézil, La courtisane et les seigneurs colorés, 1983, 121–122; Grantovskij and Raevskij, in: Ėtnogenez narodov Balkan i Severnogo Pričernomor’ja, 1984, 54–55.

- ↑ Dumézil, La courtisane et les seigneurs colorés, 1983.

- ↑ Ladislav Zgusta, "The old Ossetian Inscription from the River Zelenčuk" (Veröffentlichungen der Iranischen Kommission = Sitzungsberichte der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Klasse 486) Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1987. ISBN 3-7001-0994-6 in Kim, op.cit., 54.

Bibliography

- Lubotsky, Alexander (2002). "Scythian elements in Old Iranian" (PDF). Proceedings of the British Academy. The British Academy; azargoshnasp. 116: 189–202.

- Hinge, George (2005). "Herodot zur skythischen Sprache. Arimaspen, Amazonen und die Entdeckung des Schwarzen Meeres". Glotta (in German). 81: 86–115.

Additional literature

- Harmatta, J.: Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians, Szeged 1970.

- Mayrhofer, M.: Einiges zu den Skythen, ihrer Sprache, ihrem Nachleben. Vienna 2006.

- Zgusta, L.: Die griechischen Personennamen griechischer Städte der nördlichen Schwarzmeerküste. Die ethnischen Verhältnisse, namentlich das Verhältnis der Skythen und Sarmaten, im Lichte der Namenforschung, Prague 1955.

External links

- Scythian language A brief overview of the Scythian and Ossetian languages (in Spanish)