St. Raphael's Cathedral (Dubuque, Iowa)

| St. Raphael’s Cathedral | |

|---|---|

Cathedral and rectory | |

| Location | Dubuque, Iowa |

| Country | United States |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website |

cathedralstpats |

| History | |

| Founded | 1833 (parish) |

| Dedication | Saint Raphael |

| Dedicated | July 7, 1861 |

| Architecture | |

| Status | Cathedral/Parish |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architect(s) | John Mullany |

| Style | Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 1857 |

| Completed | 1861 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 160 feet (49 m)[1] |

| Width | 83 feet (25 m) |

| Height |

85 feet (26 m) (church) 130 feet (40 m) (tower)[2] |

| Materials |

Brick Limestone |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Dubuque |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Most Rev. Michael Jackels |

| Rector | Rev. Tom Toale |

|

St. Raphael’s Cathedral, Rectory, Convent and School | |

| |

| Location |

231 Bluff St. Dubuque, Iowa |

| Coordinates | 42°29′41.18″N 90°40′2.52″W / 42.4947722°N 90.6673667°WCoordinates: 42°29′41.18″N 90°40′2.52″W / 42.4947722°N 90.6673667°W |

| Built |

1870 (rectory) 1880s (convent) 1904 (school) |

| Architectural style |

Italianate (rectory) Second Empire (convent) Neoclassical (school) |

| Part of | Cathedral Historic District (Dubuque, Iowa) (#85002501[3]) |

| Added to NRHP | September 25, 1985 |

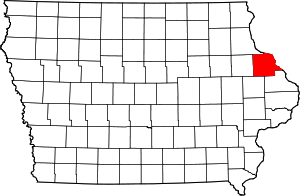

St. Raphael's Cathedral, Dubuque, Iowa, United States, is a Catholic cathedral and a parish church in the Archdiocese of Dubuque. The parish is the oldest congregation of any Christian denomination in the state of Iowa. It is a contributing property in the Cathedral Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.

History

The first years

The Cathedral parish traces its origin to 1833, when the first group of settlers gathered for Mass. Father Charles Felix Van Quickenborne, a Belgian Jesuit, organized them into a parish.[4] The parish did not have a regular church building yet, so the members met at various homes for mass. Father Quickenborne began planning for a church building, but left before the materials were assembled.

Father Charles Francis Fitzmaurice arrived in the area in 1834 and began working with the parish. He gathered materials and money to build the church, but he died during a cholera outbreak in the spring of 1835. He did not have a chance to begin work on the church building. For a time, the parishioners met in a log cabin that was set aside for worship.

The next pastor, Father Samuel Charles Mazzuchelli, OP came to Dubuque later in 1835. He reorganized the parish, and dedicated it to the Archangel Raphael. Under his guidance, a stone church building was constructed. Father Mazzuchelli personally drew the plans for this building, which served for the next 25 years. It was located just south of the current Cathedral.

In 1837 Pope Gregory XVI created the Diocese of Dubuque. In 1839 Bishop Mathias Loras, the first Bishop of Dubuque, arrived after first going to France to recruit priests and raise funds to operate the new diocese. St. Raphael's became the cathedral church for the diocese.

Growth and expansion

The next 20 years were ones of growth and expansion for the parish, and of the church in general in Iowa. Bishop Loras encouraged both Irish and German immigrants to come to Iowa from the crowded conditions in the eastern United States. As a result, the cathedral parish began to grow in size.

By 1845 St. Raphael's was usually quite crowded on Sundays. In 1849 there was a number of German families in the parish. Because of the crowded conditions, and because of the challenges of ministering to them, Bishop Loras granted permission for the Germans to form Holy Trinity parish in Dubuque. The parish eventually became known as St. Mary's. In 1853 St. Patrick's parish was built 12 blocks north to serve as a second parish for Irish families.

After St. Patrick's was founded, Bishop Loras soon came to realize that the founding of those additional parishes would only be a temporary solution. He realized that St. Raphael's parish needed a larger building.

The present building

The new Cathedral was originally planned to be built on a "Bishop's Block" on Main Street.[1] As the city's business district began to encroach on that location, Bishop Loras terminated the plan. In 1857, construction began on land just north of the old cathedral building. On July 5, 1857 a large crowd watched as the cornerstone was laid. The Cathedral was based on Magdalen College in Oxford, England. The architect was John Mullany, a local architect who designed New Melleray Abbey, and St. Mary's Church. He originally designed the Cathedral in the Romanesque Revival style however the Panic of 1857 forced a change in plans and it was constructed in the Gothic Revival style instead. Despite his failing health, construction had advanced far enough that Bishop Loras was able to offer his first mass in the new cathedral on Christmas Day, 1857. He died two months later.

The Cathedral was completed in 1861. The formal blessing and dedication was done by Bishop Clement Smyth on July 7, 1861. Father Mazzuchelli assisted with the dedication. St. Raphael's is a brick structure built on a raised basement and a stone foundation. Its main facade and the lower part of its 130-foot (40 m)[2] central tower are limestone. The bell chamber at the top of the tower is a wood structure that is encased in galvanized iron.[1] The three naves on the interior are divided by fourteen clustered wooden columns. The side elevations are seven bays in length. They are divided by buttresses and each has a lancet window in the center. Smaller windows are located over the side altars and there are three windows on either side of the chancel. Above the main entrance is a large lancet window. It was part of the original plan for the building. Even though the design of the cathedral was changed several times, the window was left as originally designed in each plan. The upper part of the window is visible from inside the church, while the lower part is hidden behind the organ. The frescos in the church were completed by Luigi Gregori, artist in residence and professor at the University of Notre Dame who had previously worked at the Vatican, and his son Constantine.[5]

The Cathedral's tower and spire were finally finished in November 1876. A number of renovations were made in the 1880s. It included new vaulting made of iron and lowering the capitals down by four feet. The stained glass windows in the church which had been imported from London were installed in 1889. Another large addition was made behind the sanctuary, which served for nearly a century as the Blessed Sacrament Chapel. The interior of the chapel was briefly seen in the movie F.I.S.T.

In 1902, a mortuary chapel was built in the lower level of the cathedral. Contained within this chapel are vaults buried underneath the floor in front of the altar. These vaults contain the bodies of the former Bishops and Archbishops of Dubuque. Two of Dubuque's archbishops are buried elsewhere. Also buried in the chapel is Archbishop Raymond Ettledorf who was a local priest who became the Nuncio to New Zealand and parts of Africa. The altar and communion rail are made of Italian marble.

Two more renovations were done in the first part of the 20th century. The first was done in 1914, and the second in 1936. A new expanded main entrance was built in 1966. The addition contained new staircases which replaced the old outdoor stairs that originally led to the side entrances. Three new sets of doors were placed at street level. Also an elevator was added to make the building more handicapped accessible.

1986 renovations

In 1986, the most extensive renovation in years was done to the church. At the time, it had been more than 50 years since the renovation. Also, the parish wanted to make some updates to the design which coincided with certain architectural and liturgical trends that were emerging in the Church at the time.[4]

Work began in the late summer and fall of 1986. The Eucharistic Chapel was deconsecrated and remodeled into a gathering space for the parish and renamed the Cathedral Center. A new Eucharistic Chapel was created by placing a wooden screen between the original high altar, and the new ad populus-oriented altar. Portions of the original communion rail were used in construction. The original ad absidem altar was left intact because of its historical significance, and a new tabernacle was placed on the altar.

Because they were a fire hazard, the dividers between the pews were removed. The layers of varnish applied over the years to the woodwork were also removed, and refinished to allow the light oak to show. The walls were painted a lighter color, and a new indirect lighting system was installed. A light green carpet was added and used throughout the building. Part of the Pietà altar was refurbished and installed in the sanctuary as the new main altar, replacing an early 1970s altar.

The sanctuary platform was extended so that more of the liturgical functions associated with the Mass took place closer to the congregation. The Archbishop's throne was replaced with a smaller, movable, less elaborate cathedra that allows him to directly face the congregation during Mass.

By November 1986 the renovations were complete. The remains of St. Cessianus were installed in the main altar during the first Mass held in the renovated Cathedral on November 23, 1986. This is in reference to the tradition in the early years of the Church when Mass was often celebrated over the tombs of saints and martyrs. The bones of St. Cessianus, a second century Roman martyr, constitute the Patronal Relic of the State of Iowa.[2] Pope Gregory XVI presented them to Bishop Loras in 1838.[6]

Pipe organ

The cathedral's pipe organ was originally built in 1890 by a builder now unknown, and was rebuilt by the Tellers-Kent Organ Company in 1937.[7] It has 46 ranks, with three manuals. The organ is composed of a number of chambers in what was the choir loft, plus another chamber along the southern wall near the front of the church. There is also a set of chimes attached to the organ.

Like a number of other organs, the pipe work is largely left out in the open rather than being contained with the case. The pipe work was artistically arranged to make a stunning visual display.

The organ console is situated in the choir area on the main level near the front of the church. It can be moved for various functions, such as Mass and recitals. In 1991, the organ was refurbished after several years of fundraising. The organ is one of the larger ones in Dubuque, and is considered one of the finest in the city.[8]

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Burials

- Bishop Mathias Loras

- Bishop Clement Smyth, OCSO

- Archbishop John Hennessy

- Archbishop Francis J.L. Beckman

- Archbishop Henry P. Rohlman

- Archbishop James J. Byrne

- Archbishop Raymond Etteldorf, Apostolic Delegate to New Zealand, then Apostolic Pro-Nuncio to Ethiopia.

Rectory, convent and school

The Cathedral shares its historic designation with the parish rectory and its former convent and school building. The rectory, which is adjacent to the Cathedral on the north, was built around 1870. The three-story brick dwelling is considered the finest example of the Italianate style in the Cathedral District.[1] The house features a low hipped roof, paired brackets on the eaves, simple window hoods, and an entrance canopy. The main entrance is flanked by side lights and it has a fan light above. The iron work detailing and the doors were originally on the mansion of A.A. Cooper, which was named Greystone and was torn down in the late 1950s.

The Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary arrived in Dubuque and started teaching in the parish school in 1843.[4] The building that became their parish convent was built as a girls' school sometime in the 1880s. It is a three-story, brick, Second Empire style structure built on a limestone foundation. It features a mansard roof, eaves, a simple cornice and stone trim. The five bay main facade has a small porch over the main entrance. The windows on the first two floors are flattened arch windows, and the third floor round arch windows are placed in dormers. The building was converted into living space for the sisters after a new school building was constructed in 1904.[1] The building has subsequently been sold by the parish and converted into senior housing.

The former St. Raphael's School building, which stands next to the Cathedral on the south, was built in 1904 in the Neoclassical style.[1] It replaced the boys' school and the girls' school buildings that were located in the rear of the cathedral property. The boys had been taught by a community of religious brothers. The boys' school building was located behind the girls' school and the Cathedral itself and has subsequently been torn down. St. Raphael's School closed in 1976 because of low enrollment. The building was sold by the parish in the mid-1980s.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lisa Hawks, Pam Myhre-Gonyier. "Cathedral Historic District (Dubuque, Iowa)" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- 1 2 3 Joseph Frazier. "The WPA Guide to 1930s Iowa". Federal Writers' Project. Retrieved 2015-05-25.

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 "St. Raphael Cathedral History". St. Raphael's Cathedral. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- ↑ Sophia Meyers (2011). Artist in Residence: Working Drawings by Luigi Gregori. Notre Dame, Indiana: The Snite Museum of Art. p. 19.

- ↑ Craughwell, Thomas J. (2011). Saints Preserved. New York: Crown Publishing Group. p. 56. ISBN 9780307590749.

- ↑ "Tellers-Kent Organ Co., 1937". OHS Pipe Organ Database. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- ↑ "Cathedral of St Raphael RC". Pipe Organ List. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. Raphael's Cathedral, Dubuque. |