| Saint Guthlac of Crowland |

|---|

|

St Guthlac holding the scourge given to him by St Bartholomew and, a demon at his feet. (The statue from the second tier of the Croyland Abbey's west front of the ruined nave; dates from the 15th century). |

| Born |

673

Mercia |

|---|

| Died |

714

Croyland |

|---|

| Venerated in |

Roman Catholic Church

Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Feast |

11 April |

|---|

Saint Guthlac of Crowland (Old English: Gūðlāc; Latin: Guthlacus; 674 – 3 April 715 AD) was a Christian saint from Lincolnshire in England. He is particularly venerated in the Fens of eastern England.

Life

Guthlac was the son of Penwalh or Penwald, a noble of the English kingdom of Mercia, and his wife Tette. His sister is also venerated as Saint Pega. As a young man, he fought in the army of Æthelred of Mercia and subsequently became a monk at Repton Monastery in Derbyshire at age twenty-four, under the abbess (Repton was a double monastery). Two years later he sought to live the life of a hermit, and moved out to the island of Croyland, now called Crowland on St Bartholomew's Day, AD 699. His early biographer Felix asserts that Guthlac could understand the strimulentes loquelas ("sibilant speech")[1] of the British-speaking demons who haunted him there, only because Guthlac had spent some time in exile among British-speaking people.[2]

Guthlac built a small oratory and cells in the side of a plundered barrow on the island, and he lived there the rest of his life until his death on 11 April in AD 714. Felix, writing within living memory of Guthlac, described his eremitic life as follows:

| “ |

Now there was in the said island a mound built of clods of earth which greedy comers to the waste had dug open, in the hope of finding treasure there; in the side of this there seemed to be a sort of cistern, and in this Guthlac the man of blessed memory began to dwell, after building a hut over it. From the time when he first inhabited this hermitage this was his unalterable rule of life: namely to wear neither wool nor linen garments nor any other sort of soft material, but he spent the whole of his solitary life wearing garments made of skins. So great indeed was the abstinence of his daily life that from the time when he began to inhabit the desert he ate no food of any kind except that after sunset he took a scrap of barley bread and a small cup of muddy water. For when the sun reached its western limits, then he thankfully tasted some little provision for the needs of this mortal life. |

” |

Guthlac suffered from ague and marsh fever.

His pious and holy ascetic life became the talk of the land, and many people visited Guthlac during his life to seek spiritual guidance from him. He gave sanctuary to Æthelbald, future king of Mercia, who was fleeing from his cousin Ceolred. Guthlac predicted that Æthelbald would become king, and Æthelbald promised to build him an abbey if his prophecy became true. Æthelbald did become king and, even though Guthlac had died two years previously, kept his word and started construction of Crowland Abbey on St Bartholomew's Day 716 AD. Guthlac's feast day is celebrated on 11 April.

St Guthlac's cross from c 1200, inscribed Hanc Petra Guthlac ..., marked the boundary of Crowland Abbey

The 8th-century Latin Vita sancti Guthlaci is written by Felix, who describes the entry of the demons into Guthlac's cell as follows:[3][4]

| “ |

They were ferocious in appearance, terrible in shape with great heads, long necks, thin faces, yellow complexions, filthy beards, shaggy ears, wild foreheads, fierce eyes, foul mouths, horses' teeth, throats vomiting flames, twisted jaws, thick lips, strident voices, singed hair, fat cheeks, pigeons breasts, scabby thighs, knotty knees, crooked legs, swollen ankles, splay feet, spreading mouths, raucous cries. For they grew so terrible to hear with their mighty shriekings that they filled almost the whole intervening space between earth and heaven with their discordant bellowings. |

” |

Felix records Guthlac's foreknowledge of his own death, conversing with angels in his last days. At the moment of death a sweet nectar-like odour emanated from his mouth, as his soul departed from his body in a beam of light while the angels sang. Guthlac had requested a lead coffin and linen winding sheet from Ecgburh, Abbess of Repton Abbey, so that his funeral rites could be performed by his sister Pega. Arriving the day after his death, she found the island of Crowland filled with the scent of ambrosia. She buried the body on the mound after three days of prayer. A year later Pega had a divine calling to move the tomb and relics to a nearby chapel: Guthlac's body was discovered incorrupt, his shroud shining with light. Subsequently Guthlac appeared in a miraculous vision to Æthelbald, prophesying he would be future King of Mercia.[5] The cult of Guthlac continued amongst a monastic community at Crowland, with the eventual foundation of Crowland Abbey as a Benedictine Order in 971. Because of a series of fires at the abbey, few records survive from prior to the 12th century. It is known that in 1136 the remains of Guthlac were moved once more and that finally in 1196 his shrine was placed above the main altar.[6]

A short Old English sermon (Vercelli XXIII) and a longer prose translation into Old English are both based on Felix's Vita. There are also two poems in Old English known as Guthlac A and Guthlac B, part of the tenth century Exeter Book, the oldest surviving collection of Anglo-Saxon poetry. The relationship of Guthlac A to Felix's Vita is debated, but Guthlac B is based on Felix's account of the saint's death.

The story of Saint Guthlac is told pictorially in the Guthlac Roll, a set of detailed illustrations of the early 13th century; it is kept in the British Library and copies are on display in Crowland Abbey.

Another account, also dating from after the Norman Conquest, was included in the Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, which like the Guthlac Roll was commissioned by the abbot of Crowland Abbey. At a time when it was being challenged by the crown, the abbey relied significantly on the cult of Guthlac, which made it a place of pilgrimage and healing. That is reflected in a shift in the emphasis from the earlier accounts of Felix and others. The post-conquest accounts portray him as a defender of the church rather than a saintly ascetic; instead of dwelling in an ancient burial mound, they depict Guthlac overseeing the building of a brick and stone chapel on the site of the abbey.[7]

The St Guthlac Fellowship

Crowland Abbey's 13th century

quatrefoil with scenes from the life of St Guthlac.

Formed in 1987, the St. Guthlac Fellowship is a group of churches which share a dedication to St Guthlac. The group comprises the following:[8]

- Crowland Abbey, Lincolnshire

- Astwick church, Bedfordshire

- All Saints Parish Church, Branston, Lincolnshire

- Our Lady and St Guthlac Roman Catholic church, Deeping St James, Lincolnshire

- St Guthlac's Church, Little Cowarne, Herefordshire

- St Guthlac's Church, Market Deeping, Lincolnshire

- Fishtoft Church, Lincolnshire

- St Guthlac, Knighton, Leicestershire

- Little Ponton Church, Lincolnshire

- Passenham Church, Northamptonshire

- St Guthlac's Church, Stathern, Leicestershire

Gallery

| Roundel from Guthlac Roll, 1210: Guthlac in contemplation |

| Roundel from Guthlac Roll, 1210: Guthlac builds a chapel at Crowland |

| Coat of Arms at Crowland Abbey show scourges and the flaying knives of St Bartholomew |

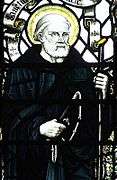

| St Guthlac, stained glass, Crowland Abbey |

|

References

- ↑ Colgrave 1985

- ↑ H. R. Loyn, Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman conquest, 2nd ed. 1991:11.

- ↑ Cohen, Jeffrey J. (2003), Medieval identity machines, Medieval cultures, 35, University of Minnesota Press, p. 149, ISBN 0-8166-4002-5 , Chapter IV, The Solitude of Guthlac

- ↑ Colgrave, Bertram (1985), Felix's Life of Saint Guthlac, Cambridge University Press, p. 103, ISBN 0-521-31386-4

- ↑ Williams 2006, pp. 205–206

- ↑ Roberts 2005

- ↑ Black 2007

- ↑ St Guthlac Fellowship

Further reading

- Primary sources

- Felix, Vita Sancti Guthlaci, early 8th-century Latin prose Life of St Guthlac:

- Colgrave, Bertram (ed. and tr.). Felix's Life of Saint Guthlac. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1956.

- Old English prose translation/adaptation (late 9tth or early 10th century) of the Life of St Guthlac by Felix:

- Gonser, P. (ed.). Das angelsächsische Prosa-Leben des heiligen Guthlac. Anglistische Forschungen 27. Heidelberg, 1909.

- Goodwin, Charles Wycliffe (ed. and tr.). The Anglo-Saxon Version of the Life of St. Guthlac, Hermit of Crowland. London, 1848.

- Two chapters from the Old English prose adaptation as incorporated into Vercelli Homily 23.

- Scragg, D.G. (ed.). The Vercelli Homilies and Related Texts. EETS 300. Oxford: University Press, 1992.

- Guthlac A and Guthlac B (Old English poems):

- Roberts, Jane (ed.). The Guthlac Poems of the Exeter Book. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979.

- Krapp, G. and E.V.K. Dobbie (eds.). The Exeter Book. Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3. 1936. 49–88

- Bradley, S.A.J. (tr.). Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Everyman, 1982.

- Muir, Bernard J. (2000), The Exeter anthology of Old English poetry: an edition of Exeter Dean and Chapter MS 3501 (2nd ed.), University of Exeter Press, ISBN 0-85989-630-7

- Harley Roll or Guthlac Roll (BL, Harleian Roll Y.6)

- Warner, G.F. (ed.). The Guthlac Roll. Roxburghe Club, 1928. 25 plates in facsimile.

- Secondary sources

- Black, John R. (2007), "Tradition and Transformation in the Cult of St. Guthlac in Early Medieval England", The Heroic Age, 10

- Olsen, Alexandra. Guthlac of Croyland: a Study of Heroic Hagiography. Washington, 1981.

- Powell, Stephen D. "The Journey Forth: Elegiac Consolation in Guthlac B." English Studies 79 (1998): 489–500.

- Roberts, Jane. "The Old English Prose Translation of Felix’s Vita Sancti Guthlaci." Studies in Earlier Old English Prose: Sixteen Original Contributions, ed. Paul E. Szarmach. Albany, 1986. 363-79.

- Roberts, Jane. "An inventory of early Guthlac materials." Mediaeval Studies 32 (1970): 193–233.

- Sharma, Manish. "A Reconsideration of Guthlac A: The Extremes of Saintliness." Journal of English and Germanic Philology 101 (2002): 185–200.

- Shook, Laurence K. "The Burial Mound in 'Guthlac A'." Modern Philology 58, 1 (Aug. 1960): 1–10.

- Soon Ai, Low. "Mental Culturation in Guthlac B." Neophilologus 81 (1997): 625–36.

- Roberts, Jane. "Guthlac of Crowland, a Saint for Middle England." Fursey Occasional Paper 3. Norwich: Fursey Pilgrims, 2009. 1–36.

- Williams, Howard (2006), Death And Memory in Early Medieval Britain, Cambridge Studies in Archaeology, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-84019-8

- Roberts, Jane (2005), Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann, eds., Hagiography and literature: the case of Guthlac of Crowland, Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom In Europe, Continuum International, pp. 69–86, ISBN 0-8264-7765-8

External links

|

|---|

| British / Welsh | |

|---|

| East Anglian | |

|---|

| East Saxon | |

|---|

Frisian,

Frankish

and Old Saxon | |

|---|

| Irish and Scottish | |

|---|

| Kentish | |

|---|

| Mercian | |

|---|

| Northumbrian | |

|---|

| Roman | |

|---|

| South Saxon | |

|---|

| West Saxon | |

|---|

| Unclear origin | |

|---|