Saint Barbara (van Eyck)

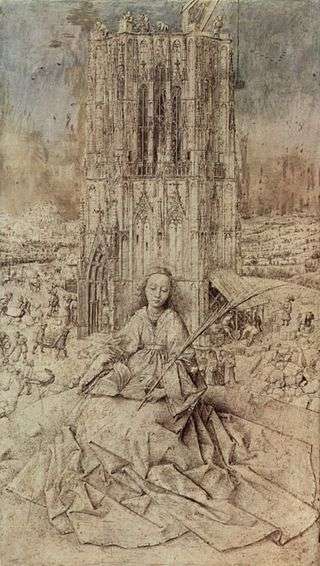

Saint Barbara is a small 1437 drawing on oak panel, signed and dated 1437 by the Netherlandish artist Jan van Eyck. It is unknown if the work is a chalk ground study in pencil for a planned oil painting, an unfinished underdrawing or a completed work in of itself. It shows Saint Barbara imprisoned in a tower by her pagan father, to preserve her from the outside world, especially from suitors he did not approve of. While there, she converted to Christianity, enraging her father and leading to her murder and martyrdom.

Found on a chalk ground, the panel was completed with brush stroke, a stylus, silverpoint, ink, oil and black pigment. The blue and ultramarine paint may be later additions.[1] Some areas and passages are more detailed than others, and it has long been debated if it is an autonomous drawing or the underdrawing for an unfinished painting. If it was intended as extant, it would be the earliest surviving drawing of any artist, although not prepared on paper or parchment. Evidence includes that the work was highly regarded at the time by Flemish aesthetics as an object in itself.[2]

The original is in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp.

St. Barbara

Saint Barbara was a Christian martyr believed to have lived in the 3rd century, and a popular saint in the late Middle Ages. According to hagiography, her wealthy and pagan father, Dioscorus, sought to preserve her from unwelcome suitors by imprisoning her in a tower. While captive, Barbara let in a priest who baptised her, an act for which she was hunted and eventually beheaded by her father.[3] She became a popular subject for artists of van Eyck's generation; another notable contemporary depiction is Robert Campin's 1438 Werl Triptych.[4]

Panel

Description

.jpg)

Barbara is shown seated reading a book, in front of a large Gothic cathedral still in the process of being built, with many workmen visible on the ground carry stone and on various parts of the tower. She has the typical narrow shoulders of a female van Eyck portrait. She is dressed in houppelande with wide sleeves, and a gown which is gathered at the waist. The opening in her bodice rises to a deep v-neck, while the trim rises to form a collar made of fur. Below the v-neck is a dark partlet, a rectangular piece of cloth with an open, standing collar, which is perhaps made of taffeta. As a maiden, she is bare headed.[5]

Three women behind and to Barbara's left are seen visiting the construction, each wearing similar houppelandes. The woman in the center raises her skirt to show her kirtle. They are each wearing headdress, probably burlets with ruffled golets draped from the head.[5]

.jpg)

The drawing is set against a blue wash sky[6] sweeping landscape rendered in browns, whites and blues, with parts only sketchily detailed.[7] The elements of the tower are highly described, and contain many complex architectural details. In a number of respects it resembles the Cologne cathedral,[8] which in 1437 was still under construction. Van Eyck had earlier depicted the cathedral as well as a view of Cologne in the Adoration of the Lamb panel of the Ghent Altarpiece.[2]

The tower, like the drawing itself,[6] is still under construction, and the panel in parts resembles a building site, being filled with figures engaged in the building project. They include workmen carrying stone, foremen and architects. According to art historian Simone Ferrari, "with its detailed and complex of small scenes, the work seems to foreshadow the paintings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder".[8]

The level of detail generally recedes as the eye extends towards the background. The craftsmen on the tower top are far less detailed than those on the ground at Barbara's level, while elements of the landscape are bare sketches. In some areas the line between the preparatory drawing and the under painting cross-over.

Frame

The lower borders of the illusionistically painted solid red marble frame[6] which contains lettering painted in such a manner so as to appear as if chiseled. The words are set in roman capitals, with punctuation at the beginning and end of the sentence.[9] The lettering reads .IOH[ANN]ES DE EYCK ME FECIT. 1437. (Jan van Eyck made me, 1437). This fact has brought a lot of question to the exact role of van Eyck's signature. If it is assumed that the work is unfinished, then the completion may refers only to the design of the picture, left to be finished by members of his workshop.[10] However, it has been pointed out that inscriptions or signatures were sometimes the first element of a painting to be completed.[8]

References

Notes

- ↑ Nash (2008), 143-5

- 1 2 Borchert (2011), 145

- ↑ Jones (2011), 104

- ↑ Stephan, Kemerdick; Sanders, Jochen. The Master of Flémalle and Rogier van der Weyden. Städel Museum, Frankfurt, 2009.

- 1 2 van Buren (2011), 160

- 1 2 3 Nash (2008), 143

- ↑ Borchert (2008), 64

- 1 2 3 Ferrari (2013), 110

- ↑ Nash (2008), 145

- ↑ Borchert (2008), 66

Sources

- Borchert, Till-Holger. Van Eyck. London: Taschen, 2008. ISBN 978-3-8228-5687-1

- Crawford Luber, Katherine. "Recognizing Van Eyck: Magical Realism in Landscape Painting". Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 91, No. 386/387, 1998

- van Buren, Anne H. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands, 1325-1515. New York: Morgan Library & Museum, 2011. ISBN 978-1-9048-3290-4

- Borchert, Till-Holger. Van Eyck to Durer: The Influence of Early Netherlandish painting on European Art, 1430–1530. London: Thames & Hudson, 2011. ISBN 978-0-500-23883-7

- Ferrari, Simone. Van Eyck. Munich: Prestel, 2013. ISBN 978-3-7913-4826-1

- Friedländer, Max Jakob. Early Netherlandish Paintings, Volume 1: The van Eycks, Petrus Christus. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967

- Harbison, Craig. Jan van Eyck: the play of realism. London: Reaktion Books, 1997. ISBN 0-948462-79-5

- Jones, Susan Frances. Van Eyck to Gossaert. National Gallery, 2011. 104. ISBN 1-85709-505-7

- Nash, Susie. Northern Renaissance art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-19-284269-2