Safe to Sleep

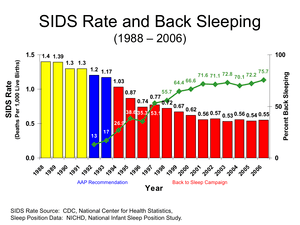

The Safe to Sleep campaign, formerly known as the Back to Sleep campaign,[1] is an initiative backed by the US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at the US National Institutes of Health to encourage parents to have their infants sleep on their backs (supine position) to reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS. Since "Safe to Sleep" was launched in 1994, the incidence of SIDS has declined by more than 50%.[2]

History

In 1992, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued the recommendation that babies sleep on their backs or sides to reduce the risk of SIDS (a statement that was later revised in 1996 to say that only the back was safest). NICHD launched the "Back to Sleep" campaign in 1994 to spread the message.

The campaign was successful in that it significantly reduced the percentage of babies sleeping on their stomachs (prone position). It was found, however, that a significant portion of African-American babies were still sleeping on their stomachs; in 1999, an African-American baby was 2.2 times more likely to die of SIDS than a white baby. Thus, then Secretary of Health and Human Services Donna Shalala and Tipper Gore refocused the "Back to Sleep" campaign on minority babies.[3]

Campaign

In 1985 Davies reported that in Hong Kong, where the common Chinese habit was for supine infant sleep position (face up), SIDS was a rare problem.[4] In 1987 the Netherlands started a campaign advising parents to place their newborn infants to sleep on their backs (supine position) instead of their stomachs (prone position).[5] This was followed by infant supine sleep position campaigns in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia in 1991, the U.S. and Sweden in 1992, and Canada in 1993.[5][6]

This advice was based on the epidemiology of SIDS and physiological evidence which shows that infants who sleep on their back have lower arousal thresholds and less slow-wave sleep (SWS) compared to infants who sleep on their stomachs.[7] In human infants sleep develops rapidly during early development. This development includes an increase in non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM sleep) which is also called quiet sleep (QS) during the first 12 months of life in association with a decrease in rapid eye movement sleep (REM sleep) which is also known as active sleep (AS).[8][9][10] In addition, slow wave sleep (SWS) which consists of stage 3 and stage 4 NREM sleep appears at 2 months of age[11][12][13][14] and it is theorized that some infants have a brain-stem defect which increases their risk of being unable to arouse from SWS (also called deep sleep) and therefore have an increased risk of SIDS due to their decreased ability to arouse from SWS.[7]

Studies have shown that preterm infants,[15][16] full-term infants,[17][18] and older infants [19] have greater time periods of quiet sleep and also decreased time awake when they are positioned to sleep on their stomachs. In both human infants and rats, arousal thresholds have been shown to be at higher levels in the electroencephalography (EEG) during slow-wave sleep.[20][21][22]

In 1992[23] a SIDS risk reduction strategy based upon lowering arousal thresholds during SWS was implemented by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) which began recommending that healthy infants be positioned to sleep on their back (supine position) or side (lateral position), instead of their stomach (prone position), when being placed down for sleep. In 1994,[24] a number of organizations in the United States combined to further communicate these non-prone sleep position recommendations and this became formally known as the "Back To Sleep" campaign. In 1996[25] the AAP further refined its sleep position recommendation by stating that infants should only be placed to sleep in the supine position and not in the prone or lateral positions.

In 1992, the first National Infant Sleep Position (NISP) Household Survey[26] was conducted to determine the usual position in which U.S. mothers placed their babies to sleep: lateral (side), prone (stomach), supine (back), other, or no usual position. According to the 1992 NISP survey, 13.0% of U.S. infants were positioned in the supine position for sleep.[26] According to the 2006 NISP survey 75.7% of infants were positioned in the supine position to sleep.[27]

See also

References

- ↑ Safe to Sleep Public Education Campaign

- ↑ NICHD Back to Sleep Campaign

- ↑ 1999.10.26:"Back to Sleep" Campaign Seeks to Reduce Incidence of SIDS in African American Populations

- ↑ Davies DP (December 1985). "Cot death in Hong Kong: a rare problem?". Lancet. 2 (8468): 1346–9. PMID 2866397. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92637-6.

- 1 2 Högberg U; Bergström E (April 2000). "Suffocated prone: the iatrogenic tragedy of SIDS". Am J Public Health. 90 (4): 527–31. PMC 1446204

. PMID 10754964. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.4.527.

. PMID 10754964. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.4.527. - ↑ Rusen ID; Liu S; Sauve R; Joseph KS; Kramer MS (2004). "Sudden infant death syndrome in Canada: trends in rates and risk factors, 1985–1998". Chronic Dis Can. 25 (1): 1–6. PMID 15298482.

- 1 2 Kattwinkel J, Hauck F.R., Moon R.Y., Malloy M and Willinger M (2006). "Infant Death Syndrome: In Reply, Bed Sharing With Unimpaired Parents Is Not an Important Risk for Sudden". Pediatrics. 117: 994–996. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2994.

- ↑ Louis J; Cannard C; Bastuji H; Challamel MJ (May 1997). "Sleep ontogenesis revisited: a longitudinal 24-hour home polygraphic study on 15 normal infants during the first two years of life". Sleep. 20 (5): 323–33. PMID 9381053.

- ↑ Navelet Y; Benoit O; Bouard G (July 1982). "Nocturnal sleep organization during the first months of life". Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 54 (1): 71–8. PMID 6177520. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(82)90233-4.

- ↑ Roffwarg HP; Muzio JN; Dement WC (April 1966). "Ontogenetic Development of the Human Sleep-Dream Cycle". Science. 152 (3722): 604–619. PMID 17779492. doi:10.1126/science.152.3722.604.

- ↑ Anders TF; Keener M (1985). "Developmental course of nighttime sleep-wake patterns in full-term and premature infants during the first year of life. I". Sleep. 8 (3): 173–92. PMID 4048734.

- ↑ Bes F; Schulz H; Navelet Y; Salzarulo P (February 1991). "The distribution of slow-wave sleep across the night: a comparison for infants, children, and adults". Sleep. 14 (1): 5–12. PMID 1811320.

- ↑ Coons S; Guilleminault C (June 1982). "Development of sleep-wake patterns and non-rapid eye movement sleep stages during the first six months of life in normal infants". Pediatrics. 69 (6): 793–8. PMID 7079046.

- ↑ Fagioli I; Salzarulo P (April 1982). "Sleep states development in the first year of life assessed through 24-h recordings". Early Hum. Dev. 6 (2): 215–28. PMID 7094858. doi:10.1016/0378-3782(82)90109-8.

- ↑ Myers MM, Fifer WP, Schaeffer L, et al. (June 1998). "Effects of sleeping position and time after feeding on the organization of sleep/wake states in prematurely born infants". Sleep. 21 (4): 343–9. PMID 9646378.

- ↑ Sahni R, Saluja D, Schulze KF, et al. (September 2002). "Quality of diet, body position, and time after feeding influence behavioral states in low birth weight infants". Pediatr Res. 52 (3): 399–404. PMID 12193675. doi:10.1203/00006450-200209000-00016.

- ↑ Brackbill Y; Douthitt TC; West H (January 1973). "Psychophysiologic effects in the neonate of prone versus supine placement". J Pediatr. 82 (1): 82–4. PMID 4681872. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(73)80017-4.

- ↑ Amemiya F; Vos JE; Prechtl HF (May 1991). "Effects of prone and supine position on heart rate, respiratory rate and motor activity in fullterm newborn infants". Brain Dev. 13 (3): 148–54. PMID 1928606. doi:10.1016/S0387-7604(12)80020-9.

- ↑ Kahn A; Rebuffat E; Sottiaux M; Dufour D; Cadranel S; Reiterer F (February 1991). "Arousals induced by proximal esophageal reflux in infants". Sleep. 14 (1): 39–42. PMID 1811318.

- ↑ Ashton R (April 1973). "The influence of state and prandial condition upon the reactivity of the newborn to auditory stimulation". J Exp Child Psychol. 15 (2): 315–27. PMID 4735894. doi:10.1016/0022-0965(73)90152-5.

- ↑ Rechtschaffen A; Hauri P; Zeitlin M (June 1966). "Auditory awakening thresholds in REM and NREM sleep stages". Percept Mot Skills. 22 (3): 927–42. PMID 5963124. doi:10.2466/pms.1966.22.3.927.

- ↑ Neckelmann D; Ursin R (August 1993). "Sleep stages and EEG power spectrum in relation to acoustical stimulus arousal threshold in the rat". Sleep. 16 (5): 467–77. PMID 8378687.

- ↑ "American Academy of Pediatrics AAP Task Force on Infant Positioning and SIDS: Positioning and SIDS". Pediatrics. 89 (6 Pt 1): 1120–6. June 1992. PMID 1503575.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Human Services. "BACK TO SLEEP" CAMPAIGN SEEKS To Reduce Inicidence of SIDS In African American Populations PressRelease. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/1999pres/991026.html Tuesday, October 26, 1999

- ↑ "Positioning and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): update. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Infant Positioning and SIDS". Pediatrics. 98 (6 Pt 1): 1216–8. December 1996. PMID 8951285.

- 1 2 National Infant Sleep Position Household Survey. Summary Data 1992. http://dccwww.bumc.bu.edu/ChimeNisp/NISP_Data.asp updated: 09/04/07

- ↑ National Infant Sleep Position Household Survey. Summary Data 2006. http://dccwww.bumc.bu.edu/ChimeNisp/NISP_Data.asp updated: 09/04/07