Sack of Rome (1527)

| Sack of Rome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the League of Cognac | |||||||

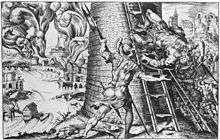

The sack of Rome in 1527, by Johannes Lingelbach, 17th century (private collection). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

5,000 Condottieri militia, 189 Swiss Guards | 20,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 500 dead, wounded, or captured | 15,000 | ||||||

| 45,000 civilians dead, wounded, or exiled | |||||||

The Sack of Rome on 6 May 1527 was a military event carried out by the mutinous troops of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, in Rome, then part of the Papal States. It marked a crucial imperial victory in the conflict between Charles and the League of Cognac (1526–1529)—the alliance of France, Milan, Venice, Florence and the Papacy.

Preceding events

Pope Clement VII had given his support to the Kingdom of France in an attempt to alter the balance of power in the region, and free the Papacy from dependency, i.e. a growing weakness to "Imperial domination" by the Holy Roman Empire (and the Habsburg dynasty).

The army of the Holy Roman Emperor defeated the French army in Italy, but funds were not available to pay the soldiers. The 34,000 Imperial troops mutinied and forced their commander, Charles III, Duke of Bourbon and Constable of France, to lead them towards Rome. Apart from some 6,000 Spaniards under the Duke, the army included some 14,000 Landsknechts under Georg von Frundsberg, some Italian infantry led by Fabrizio Maramaldo, the powerful Italian cardinal Pompeo Colonna and Luigi Gonzaga, and also some cavalry under command of Ferdinando Gonzaga and Philibert, Prince of Orange. Though Martin Luther himself was not in favor of it, some who considered themselves followers of Luther's Protestant movement viewed the Papal capital as a target for religious reasons, and shared with the soldiers a desire for the sack and pillage of a city that appeared to be an easy target. Numerous bandits, along with the League's deserters, joined the army during its march.

The Duke left Arezzo on 20 April 1527, taking advantage of the chaos among the Venetians and their allies after a revolt which had broken out in Florence against the Medici. In this way, the largely undisciplined troops sacked Acquapendente and San Lorenzo alle Grotte, and occupied Viterbo and Ronciglione, reaching the walls of Rome on 5 May.

Sack

The troops defending Rome were not at all numerous, consisting of 5,000 militiamen led by Renzo da Ceri and 189[1] Papal Swiss Guard. The city's fortifications included the massive walls, and it possessed a good artillery force, which the Imperial army lacked. Duke Charles needed to conquer the city swiftly, to avoid the risk of being trapped between the besieged city and the League's army.

On 6 May, the Imperial army attacked the walls at the Gianicolo and Vatican Hills. Duke Charles was fatally wounded in the assault, allegedly shot by Benvenuto Cellini. The Duke was wearing his famous white cloak to mark him out to his troops, but it also had the unintended consequence of pointing him out as the leader to his enemies. The death of the last respected command authority among the Imperial army caused any restraint in the soldiers to disappear, and they easily captured the walls of Rome the same day. Philibert of Châlon took command of the armies, but he was not as popular or feared, leaving him with little authority. One of the Swiss Guard's most notable hours occurred at this time. Almost the entire guard was massacred by Imperial troops on the steps of St Peter's Basilica. Of 189 guards on duty only the 42 who accompanied the pope survived, but the bravery of the rearguard ensured that Pope Clement VII escaped to safety, down the Passetto di Borgo, a secret corridor which still links the Vatican City to Castel Sant'Angelo.

After the brutal execution of some 1,000 defenders of the Papal capital and shrines, the pillage began. Churches and monasteries, as well as the palaces of prelates and cardinals, were looted and destroyed. Even pro-Imperial cardinals had to pay to save their properties from the rampaging soldiers. On 8 May, Cardinal Pompeo Colonna, a personal enemy of Clement VII, entered the city. He was followed by peasants from his fiefs, who had come to avenge the sacks they had suffered by Papal armies. However, Colonna was touched by the pitiful conditions of the city and hosted in his palace a number of Roman citizens.

The Vatican Library was saved because Philibert had set up his headquarters there.[2][lower-alpha 1] After three days of ravages, Philibert ordered the sack to cease, but few obeyed. In the meantime, Clement remained a prisoner in Castel Sant'Angelo. Francesco Maria della Rovere and Michele Antonio of Saluzzo arrived with troops on 1 June in Monterosi, north of the city. Their cautious behaviour prevented them from obtaining an easy victory against the now totally undisciplined Imperial troops. On 6 June, Clement VII surrendered, and agreed to pay a ransom of 400,000 ducati in exchange for his life; conditions included the cession of Parma, Piacenza, Civitavecchia and Modena to the Holy Roman Empire (however, only the last could be occupied in fact). At the same time Venice took advantage of this situation to capture Cervia and Ravenna, while Sigismondo Malatesta returned to Rimini.

Aftermath

Emperor Charles V was greatly embarrassed by the fact that he had been powerless to stop his troops striking against Pope Clement VII and imprisoning him. Some may argue that Charles was partially responsible for the Sack of Rome since he expressed his desire for a private audience with Pope Clement and his men took action into their own hands. Clement spent the rest of his life trying to steer clear of conflict with the emperor, avoiding decisions that could displease Charles, but making the pope powerless. Without any qualms and without conditions, Clement agreed to cede the worldly and political possessions of the bishopric of Utrecht to the Habsburgs.

In the view of many at the time and since, fear of a repeat of the sack of Rome, along with the pope's virtual imprisonment as a result of it, made it impossible for him to offend the Emperor by granting England's King Henry VIII the annulment that he sought of his marriage to the Emperor's aunt Catherine of Aragon, so Henry eventually broke with Rome, thus leading to the English Reformation.[3][4]

The event marked the end of the Roman Renaissance, damaged the papacy's prestige and freed the Emperor's hands to act against the Reformation in Germany and against the rebellious German princes allied with Luther. Nevertheless, Martin Luther commented: "Christ reigns in such a way that the Emperor who persecutes Luther for the Pope is forced to destroy the Pope for Luther" (LW 49:169).

The population of Rome dropped from some 55,000 before the attack to 10,000. An estimated 6,000 to 12,000 people were murdered. Many Imperial soldiers also died in the following months (they remained in the city until February 1528) from diseases caused by the large number of unburied dead bodies in the city. The pillage only ended when, after eight months, the food ran out, there was no one left to ransom and plague appeared.[5]

In commemoration of the Sack and the Guard's bravery, recruits to the Swiss Guard are sworn in on 6 May every year.

Notes

- ↑ The library was not, however, undamaged or unmolested. The sack is thought to have been the occasion of the loss or destruction of Nicolaus Germanus's globes of the terrestrial and celestial spheres, the first modern globes.

References

Citations

- ↑ http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/swiss_guard/swissguard/storia_en.htm

- ↑ Durant, Will. 1953. The Renaissance. Simon & Schuster.

- ↑ Holmes (1993), p192

- ↑ Froude (1891), p35, pp90-91, pp96-97 Note: the link goes to page 480, then click the View All option

- ↑ Watson, Peter -- Boorstin, Op. cit., page 180

Bibliography

- Froude, James Anthony (1891). The Divorce Of Catherine Of Aragon. Kessinger Publishing, reprint 2005. ISBN 1417971096.

- Holmes, David L. (1993). A Brief History of the Episcopal Church. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1563380609.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1985). The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam. Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 0345308239.

See also

- Sack of Rome for other sacks of Rome

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sack of Rome (1527). |

- Pope's guards celebrate 500 years, BBC News Online; dated and retrieved 22 January 2006

- Vatican's honour to Swiss Guards, BBC News Online; dated and retrieved 6 May 2006

Coordinates: 41°50′N 12°30′E / 41.833°N 12.500°E