Sami people

| Sámit | |

|---|---|

|

| |

A Sami choir in concert in 2003 | |

| Total population | |

| 137,477 (est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| 37,890–60,000[1][2] | |

| 14,600–36,000[2][3] | |

| 9,350[4] | |

| 1,991[5] | |

| 136[6] | |

| Languages | |

|

Sami languages (Akkala, Inari, Kildin, Kemi, Lule, Northern, Pite, Skolt, Ter, Southern, Ume) Russian, Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheranism (including Laestadianism), Eastern Orthodoxy, Sami shamanism, Conscious Atheism, non-adherence | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Finnic peoples | |

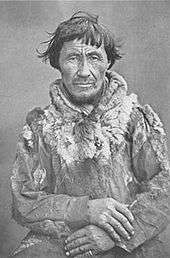

The Sami people (also Sámi or Saami, traditionally known in English as Lapps or Laplanders) are an indigenous Finno-Ugric people inhabiting the Arctic area of Sápmi, which today encompasses parts of far northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. The Sami are the only indigenous people of Scandinavia recognized and protected under the international conventions of indigenous peoples, and are hence the northernmost indigenous people of Europe.[7] Sami ancestral lands are not well-defined. Their traditional languages are the Sami languages and are classified as a branch of the Uralic language family.

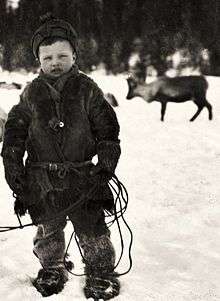

Traditionally, the Sami have pursued a variety of livelihoods, including coastal fishing, fur trapping, and sheep herding. Their best-known means of livelihood is semi-nomadic reindeer herding. Currently about 10% of the Sami are connected to reindeer herding, providing them with meat, fur, and transportation. 2,800 Sami people are actively involved in herding on a full-time basis.[8] For traditional, environmental, cultural, and political reasons, reindeer herding is legally reserved for only Sami people in some regions of the Nordic countries.[9]

Etymologies

The Sámi are often known in other languages by the exonyms Lap, Lapp, or Laplanders. Some Sami regard these as pejorative terms,[10][11][12] while others accept at least the name Lappland.[12] Variants of the name Lapp were originally used in Sweden and Finland and, through Swedish, adopted by many major European languages: English: Lapps; German, Dutch: Lappen; French: Lapons; Greek: Λάπωνες (Lápōnes); Hungarian: lappok; Italian: Lapponi; Polish: Lapończycy; Portuguese: Lapões; Spanish: Lapones; Romanian: laponi; Turkish: Lapon. In Russian the corresponding term is лопари́ (lopari) and in Ukrainian лопарі́ (lopari).

The first probable historical mention of the Sami, naming them Fenni, was by Tacitus, about 98 A.D.[13] Variants of Finn or Fenni were in wide use in ancient times, judging from the names Fenni and Phinnoi in classical Roman and Greek works. Finn (or variants, such as skridfinn, "striding Finn") was the name originally used by Norse speakers (and their proto-Norse speaking ancestors) to refer to the Sami, as attested in the Icelandic Eddas and Norse sagas (11th to 14th centuries). The etymology is somewhat uncertain, but the consensus seems to be that it is related to Old Norse finna, from proto-Germanic *finthanan ("to find"),[14] the logic being that the Sami, as hunter-gatherers "found" their food, rather than grew it. As Old Norse gradually developed into the separate Scandinavian languages, Swedes apparently took to using Finn exclusively to refer to inhabitants of Finland, while Sami came to be called Lapps. In Norway, however, Sami were still called Finns at least until the modern era (reflected in toponyms like Finnmark, Finnsnes, Finnfjord and Finnøy) and some Northern Norwegians will still occasionally use Finn to refer to Sami people, although the Sami themselves now consider this to be a pejorative term. Finnish immigrants to Northern Norway in the 18th and 19th centuries were referred to as "Kvens" to distinguish them from the Sami "Finns". Ethnic Finns are a distinct group from Sami.

The word Lapp can be traced to Old Swedish lapper, Icelandic lappir (plural), probably of Finnish origin; compare Finnish lappalainen "Lapp", Lappi "Lapland" (possibly meaning "wilderness in the north"), the original meaning being unknown.[15][16] It is unknown how the word Lapp came into the Norse language, but one of the first written mentions of the term is in the Gesta Danorum by 12th-century Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, who referred to the two Lappias, although he still referred to the Sami as (Skrid-)Finns.[17][18] In fact, Saxo never explicitly connects the Sami with the "two Laplands". The term "Lapp" was popularized and became the standard terminology by the work of Johannes Schefferus, Acta Lapponica (1673), but was also used earlier by Olaus Magnus in his Description of the Northern people (1555). There is another suggestion that it originally meant "wilds".

In Finland and Sweden, Lapp is common in place names, such as Lappi (Satakunta), Lappeenranta (South Karelia) and Lapinlahti (North Savo) in Finland; and Lapp (Stockholm County), Lappe (Södermanland) and Lappabo (Småland) in Sweden. As already mentioned, Finn is a common element in Norwegian (particularly Northern Norwegian) place names, whereas Lapp is exceedingly rare.

In the North Sámi language, láhppon olmmoš means a person who is lost (from the verb láhppot, to get lost).

Sámi refer to themselves as Sámit (the Sámis) or Sápmelaš (of Sámi kin), the word Sámi being inflected into various grammatical forms. It has been proposed that Sámi (presumably borrowed from the Proto-Finnic word), Häme (Finnish for Tavastia) ( ← Proto-Finnic *šämä, the second ä still being found in the archaic derivation Hämäläinen), and perhaps Suomi (Finnish for Finland) (← *sōme-/sōma-, compare suomalainen, supposedly borrowed from a Proto-Germanic source *sōma- from Proto-Baltic *sāma-, in turn borrowed from Proto-Finnic *šämä) are of the same origin and ultimately borrowed from the Baltic word *žēmē, meaning "land".[19] The Baltic word is cognate with Slavic земля (zemlja), which also means "land".[20] The Sámi institutions—notably the parliaments, radio and TV stations, theatres, etc.—all use the term Sámi, including when addressing outsiders in Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, or English. In Norwegian, the Sámi are today referred to by the Norwegianized form same, whereas the word lapp would be considered archaic and pejorative. In northernmost Sweden, the word lapp is in use and not seen as derogatory or taboo.

Terminological issues in Finnish are somewhat different. Finns living in Finnish Lapland generally call themselves lappilainen, whereas the similar word for the Sámi people is lappalainen. This can be confusing for foreign visitors because of the similar lives Finns and Sámi people live today in Lapland. Lappalainen is also a common family name in Finland. As in the Scandinavian languages, lappalainen is often considered archaic or pejorative, and saamelainen is used instead, at least in official contexts.

History

Since prehistoric times,[21][22] the Sami people of Arctic Europe have lived and worked in an area that stretches over the northern parts of the regions now known as Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Russian Kola Peninsula. They have inhabited the northern arctic and sub-arctic regions of Fenno-Scandinavia and Russia for at least 5,000 years.[23] The Sami are counted among the Arctic peoples and are members of circumpolar groups such as the Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat.[24]

Petroglyphs and archeological findings such as settlements dating from about 10,000 B.C. can be found in the traditional lands of the Sami.[25] The now-obsolete term for the archaeological culture of these hunters and gatherers of the late Paleolithic and early Mesolithic is Komsa. A cultural continuity between these stone-age people and the Sami can be assumed due to evidence such as the similarities in the decoration patterns of archeological bone objects and Sami decoration patterns, and there is no archeological evidence of this population being replaced by another.[25]

Recent archaeological discoveries in Finnish Lapland were originally seen as the continental version of the Komsa culture about the same age as the earliest finds on the coast of Norway.[26][27] It is hypothesized that the Komsa followed receding glaciers inland from the Arctic coast at the end of the last ice age (between 11,000 and 8000 years B.C.) as new land opened up for settlement (e.g., modern Finnmark area in the northeast, to the coast of the Kola Peninsula).[28] Since the Sami are the earliest ethnic group in the area, they are consequently considered an indigenous population of the area.[29]

Southern limits of Sami settlement in the past

How far south the Sami extended in the past has been debated among historians and archeologists for many years. The Norwegian historian Yngvar Nielsen, commissioned by the Norwegian government in 1889 to determine this question to settle contemporary questions of Sami land rights, concluded that the Sami had lived no farther south than Lierne in Nord-Trøndelag county until around 1500, when they started moving south, reaching the area around Lake Femund in the 18th century.[30] This hypothesis is still accepted among many historians, but has been the subject of scholarly debate in the 21st century. In recent years, several archaeological finds indicate a Sami presence in southern Norway in the Middle Ages, and southern Sweden,[23] including finds in Lesja, in Vang in Valdres and in Hol and Ål in Hallingdal.[31] Proponents of the Sami interpretations of these finds assume a mixed population of Norse and Sami people in the mountainous areas of southern Norway in the Middle Ages.[32]

Origins of the Norwegian Sea Sami

The bubonic plague

Until the arrival of bubonic plague in northern Norway in 1349, the Sami and the Norwegians occupied very separate economic niches.[33] The Sami hunted reindeer and fished for their livelihood. The Norwegians, who were concentrated on the outer islands and near the mouths of the fjords, had access to the major European trade routes so that, in addition to marginal farming in the Nordland, Troms, and Finnmark counties, they were able to establish commerce, supplying fish in trade for products from the south.[34] The two groups co-existed using two different food resources.[34] According to old Nordic texts, the Sea Sami and the Mountain Sami are two classes of the same people and not two different ethnic groups as had been erroneously believed.[35]

This social economic balance greatly changed with the introduction of the bubonic plague to northern Norway in December 1349. The Norwegians were closely connected to the greater European trade routes, along which the plague traveled; consequently, they were infected and died at a far higher rate than Sami in the interior. Of all the states in the region, Norway suffered the most from this plague.[36] Depending on the parish, sixty to seventy-six percent of the northern Norwegian farms were abandoned following the plague,[37] while land-rents, another possible measure of the population numbers, dropped down to between 9–28% of pre-plague rents.[38] Although the population of northern Norway is sparse compared to southern Europe, the spread of the disease was just as rapid.[39] The method of movement of the plague-infested flea (Xenopsylla cheopsis) from the south was in wooden barrels holding wheat, rye, or wool—where the fleas could live, and even reproduce, for several months at a time.[40] The Sami, having a non-wheat or -rye diet, eating fish and reindeer meat, living in communities detached from the Norwegians, and being only weakly connected to the European trade routes, fared far better than the Norwegians.[41]

Fishing industry

Fishing has always been the main livelihood for the many Sami living permanently in coastal areas.[42] Archeological research shows that the Sami have lived along the coast and once lived much farther south in the past, and they were also involved in work other than reindeer herding (e.g., fishing, agriculture, iron work).[23] The fishing along the north Norwegian coast, especially in the Lofoten and Vesterålen islands, is quite productive with a variety of fish, and during medieval times, it was a major source of income for both the fisherman and the Norwegian monarchy.[43] With such massive population drops caused by the Black Death, the tax revenues from this industry greatly diminished. Because of the huge economic profits that could be had from these fisheries, the local authorities offered incentives to the Sami—faced with their own population pressures—to settle on the newly vacant farms.[44] This started the economic division between the Sea Sami (sjøsamene), who fished extensively off the coast, and the Mountain Sami (fjellsamene, innlandssamene), who continued to hunt reindeer and small-game animals. They later herded reindeer. Even as late as the early 18th century, there were many Sami who were still settling on these farms left abandoned from the 1350s.[45][46] After many years of continuous migration, these Sea Sami became far more numerous than the reindeer mountain Sami, who today only make up 10% of all Sami. In contemporary times, there are also ongoing consultations between the Government of Norway and the Sami Parliament regarding the right of the coastal Sami to fish in the seas on the basis of historical use and international law.[47] State regulation of sea fisheries underwent drastic change in the late 1980s. The regulation linked quotas to vessels and not to fishers. These newly calculated quotas were distributed free of cost to larger vessels on the basis of the amount of the catch in previous years, resulting in small vessels in Sami districts falling outside the new quota system to a large degree.[42][48]

Mountain Sami

As the Sea Sami settled along Norway's fjords and inland waterways pursuing a combination of farming, cattle raising, trapping and fishing, the smaller minority of the Mountain Sami continued to hunt wild reindeer. Around 1500, they started to tame these animals into herding groups, becoming the well-known reindeer nomads, often portrayed by outsiders as following the archetypal Sami lifestyle. The Mountain Sami faced the fact that they had to pay taxes to three nation-states, Norway, Sweden and Russia, as they crossed the borders of each of the respective countries following the annual reindeer migrations, which caused much resentment over the years.[49] Sweden made the Sami work in a slavemine at Nasafjäll, causing many Samis to flee from the area, so a large part of the provinces previously used by Pite and Lule Samis is depopulated. Government troops were ordered to prevent the Sami from fleeing.[49]

Post-1800s

For long periods of time, the Sami lifestyle thrived because of its adaptation to the Arctic environment. Indeed, throughout the 18th century, as Norwegians of Northern Norway suffered from low fish prices and consequent depopulation, the Sami cultural element was strengthened, since the Sami were mostly independent of supplies from Southern Norway.

However, during the 19th century, Norwegian authorities pressured the Sami to make Norwegian language and culture universal. Strong economic development of the north also ensued, giving Norwegian culture and language higher status. On the Swedish and Finnish sides, the authorities were less militant, although the Sami language was forbidden in schools and strong economic development in the north led to weakened cultural and economic status for the Sami. From 1913 to 1920, the Swedish race-segregation political movement created a race-based biological institute that collected research material from living people and graves, and sterilized Sami women. Throughout history, Swedish settlers were encouraged to move to the northern regions through incentives such as land and water rights, tax allowances, and military exemptions.[50]

The strongest pressure took place from around 1900 to 1940, when Norway invested considerable money and effort to wipe out Sami culture. Anyone who wanted to buy or lease state lands for agriculture in Finnmark had to prove knowledge of the Norwegian language and had to register with a Norwegian name. This caused the dislocation of Sami people in the 1920s, which increased the gap between local Sami groups (something still present today) that sometimes has the character of an internal Sami ethnic conflict. In 1913, the Norwegian parliament passed a bill on "native act land" to allocate the best and most useful lands to Norwegian settlers. Another factor was the scorched earth policy conducted by the German army, resulting in heavy war destruction in northern Finland and northern Norway in 1944–45, destroying all existing houses, or kota, and visible traces of Sami culture. After World War II the pressure was relaxed though the legacy was evident into recent times, such as the 1970s law limiting the size of any house Sami people were allowed to build.

The controversy over the construction of the hydro-electric power station in Alta in 1979 brought Sami rights onto the political agenda. In August 1986, the national anthem ("Sámi soga lávlla") and flag (Sami flag) of the Sami people were created. In 1989, the first Sami parliament in Norway was elected. In 2005, the Finnmark Act was passed in the Norwegian parliament giving the Sami parliament and the Finnmark Provincial council a joint responsibility of administering the land areas previously considered state property. These areas (96% of the provincial area), which have always been used primarily by the Sami, now belong officially to the people of the province, whether Sami or Norwegian, and not to the Norwegian state.

Contemporary

The indigenous Sami population is a mostly urbanised demographic, but a substantial number live in villages in the high arctic. The Sami are still coping with the cultural consequences of language and culture loss related to generations of Sami children taken to missionary and/or state-run boarding schools and the legacy of laws that were created to deny the Sami rights (e.g., to their beliefs, language, land and to the practice of traditional livelihoods). The Sami are experiencing cultural and environmental threats,[22] including oil exploration, mining, dam building, logging, climate change, military bombing ranges, tourism and commercial development.

- Natural-resource prospecting

Sapmi is rich in precious metals, oil, and natural gas. Mining activities in Arctic Sapmi cause controversy when they are in grazing and calving areas. Mining projects are rejected by the Sami Parliament in the Finnmark area. The Sami Parliament demands that resources and mineral exploration should benefit mainly the local Sami communities and population, as the proposed mines are in Sami lands and will affect their ability to maintain their traditional livelihood.[51] Mining locations even include ancient Sami spaces that are designated as ecologically protected areas, such as the Vindelfjällen Nature Reserve.[52] In Russia's Kola Peninsula, vast areas have already been destroyed by mining and smelting activities, and further development is imminent. This includes oil and natural gas exploration in the Barents Sea. There is a gas pipeline that stretches across the Kola Peninsula. Oil spills affect fishing and the construction of roads. Power lines may cut off access to reindeer calving grounds and sacred sites.[53]

- Mining

In Kallak (Sami: Gállok) a group of indigenous and non-indigenous activists protested to stop the UK-based mining company Beowulf from carrying on a drilling program in reindeer winter grazing lands.[54] There is often local opposition to new mining projects where environmental impacts are perceived to be very large. New modern mines eliminate the need for many types of jobs and new job creation.[55] ILO Convention No. 169 would grant rights to the Sami people to their land and give them power in matters that affect their future.[56] Swedish taxes on minerals are low in an international comparison in order to increase mineral exploration. There are also few plans for mine reclamation.

- Logging

In northern Finland, there has been a longstanding dispute over the destruction of forests, which prevents reindeer from migrating between seasonal feeding grounds and destroys supplies of lichen that grow on the upper branches of older trees. This lichen is the reindeer's only source of sustenance during the winter months, when snow is deep. The logging has been under the control of the state-run forest system.[57] Greenpeace, reindeer herders, and Sami organisations carried out a historic joint campaign, and in 2010, Sami reindeer herders won some time as a result of these court cases. Industrial logging has now been pushed back from the most important forest areas either permanently or for the next 20 years, though there are still threats, such as mining and construction plans of holiday resorts on the protected shorelines of Lake Inari.[58]

- Military activities

Government authorities and NATO have built bombing-practice ranges in Sami areas in northern Norway and Sweden. These regions have served as reindeer calving and summer grounds for thousands of years, and contain many ancient Sami sacred sites.[59][60]

- Land rights

The Swedish government has allowed the world's largest onshore wind farm to be built in Piteå, in the Arctic region where the Eastern Kikkejaure village has its winter reindeer pastures. The wind farm will consist of more than 1,000 wind turbines, one 80 mil and an extensive road infrastructure, which means that the feasibility of using the area for winter grazing in practice is impossible. Sweden has received strong international criticism, including by the UN Racial Discrimination Committee and the Human Rights Committee, that Sweden violates Sami landrättigheter (land rights), including by not regulating industry. In Norway some Lappish politicians (for example - Aili Keskitalo) suggest giving the Sami Parliament a special veto right on planned mining projects.[61]

- Water rights

State regulation of sea fisheries underwent drastic change in the late 1980s. The regulation linked quotas to vessels and not to fishers. These newly calculated quotas were distributed free of cost to larger vessels on the basis of the amount of the catch in previous years, resulting in small vessels in Sami districts falling outside the new quota system to a large degree.

The Sami recently stopped a water-prospecting venture that threatened to turn an ancient sacred site and natural spring called Suttesaja into a large-scale water-bottling plant for the world market—without notification or consultation with the local Sami people, who make up 70 percent of the population. The Finnish National Board of Antiquities has registered the area as a heritage site of cultural and historical significance, and the stream itself is part of the Deatnu/Tana watershed, which is home to Europe's largest salmon river, an important source of Sami livelihood.[62]

In Norway, government plans for the construction of a hydroelectric power plant in the Alta river in Finnmark in northern Norway led to a political controversy and the rallying of the Sami popular movement in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As a result, the opposition in the Alta controversy brought attention to not only environmental issues but also the issue of Sami rights.

- Climate change and environment

Reindeer have major cultural and economic significance for indigenous peoples of the North. The human-ecological systems in the North, like reindeer pastoralism, are sensitive to change, perhaps more than in virtually any other region of the globe, due in part to the variability of the Arctic climate and ecosystem and the characteristic ways of life of indigenous Arctic peoples.[63]

The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster caused nuclear fallout in the sensitive Arctic ecosystems and poisoned fish, meat[64] and berries. Lichens and mosses are two of the main forms of vegetation in the Arctic and are highly susceptible to airborne pollutants and heavy metals. Since many do not have roots, they absorb nutrients, and toxic compounds, through their leaves. The lichens accumulated airborne radiation, and 73,000 reindeer had to be destroyed as "unfit" for human consumption in Sweden alone. The government promised Sami indemnification, which was not acted upon by government.

Radioactive wastes and spent nuclear fuel have been stored in the waters off the Kola Peninsula, including locations that are only "two kilometers" from places where Sami live. There are a minimum of five "dumps" where spent nuclear fuel and other radioactive waste are being deposited in the Kola Peninsula, often with little concern for the surrounding environment or population.[65]

- Tourism

The tourism industry in Finland has been criticized for turning Sami culture into a marketing tool by promoting opportunities to experience "authentic" Sami ceremonies and lifestyle. At many tourist locales, non-Samis dress in inaccurate replicas of Sami traditional clothing, and gift shops sell crude reproductions of Sami handicraft. One popular "ceremony", crossing the Arctic Circle, actually has no significance in Sami spirituality. To the Sami, this is an insulting display of cultural exploitation.[66]

Discrimination against the Sami

The Sami have for centuries been the subject of discrimination and abuse by the dominant cultures claiming possession of their lands right unto the present day.[67] They have never been a single community in a single region of Lapland, which until recently was considered only a cultural region.[68]

Norway has been greatly criticized by the international community for the politics of Norwegianization of and discrimination against the aboriginal population of the country.[69] On 8 April 2011, the UN Racial Discrimination Committee recommendations were handed over to Norway; these addressed many issues, including the educational situation for students needing bilingual education in Sami. One committee recommendation was that no language be allowed to be a basis for discrimination in the Norwegian anti-discrimination laws, and it recommended wording of Racial Discrimination Convention Article 1 contained in the Act. Further points of recommendation concerning the Sami population in Norway included the incorporation of the racial Convention through the Human Rights Act, improving the availability and quality of interpreter services, and equality of the civil Ombudsman's recommendations for action. A new present status report was to have been ready by the end of 2012.[70]

Even in Finland, where Sami children, like all Finnish children, are entitled to day care and language instruction in their own language, the Finnish government has denied funding for these rights in most of the country, including even in Rovaniemi, the largest municipality in Finnish Lapland. Sami activists have pushed for nationwide application of these basic rights.[71]

As in the other countries claiming sovereignty over Sami lands, Sami activists' efforts in Finland in the 20th century achieved limited government recognition of the Samis' rights as a recognized minority, but the Finnish government has clung unyieldingly to its legally enforced premise that the Sami must "prove" their land ownership, an idea incompatible with and antithetical to the traditional reindeer-herding Sami way of life. This has effectively allowed the Finnish government to take without compensation, motivated by economic gain, land occupied by the Sami for centuries.[72]

Official Sami policy

Norway

The Sami have been recognized as an indigenous people in Norway (1990 according to ILO convention 169 as described below), and hence, according to international law, the Sami people in Norway are entitled special protection and rights. The legal foundation of the Sami policy is:[73]

- Article 110a of the Norwegian Constitution.

- The Sami Act (act of 12 June 1987 No. 56 concerning the Sami Parliament (the Sámediggi) and other legal matters pertaining to the Samis).

The constitutional amendment states: "It is the responsibility of the authorities of the State to create conditions enabling the Sami people to preserve and develop its language, culture and way of life." This provides a legal and political protection of the Sami language, culture and society. In addition the "amendment implies a legal, political and moral obligation for Norwegian authorities to create an environment conducive to the Samis themselves influencing on the development of the Sami community" (ibid.).

The Sami Act provides special rights for the Sami people (ibid.):

- "... the Samis shall have their own national Sami Parliament elected by and amongst the Samis" (Chapter 1–2).

- The Sami people shall decide the area of activity of the Norwegian Sami Parliament.

- The Sami and Norwegian languages have equal standing in Norway (section 15; Chapter 3 contains details with regards to the use of the Sami language).

In addition, the Sami have special rights to reindeer husbandry.

The Norwegian Sami Parliament also elects 50% of the members to the board of the Finnmark Estate, which controls 95% of the land in the county of Finnmark.

Norway has also accepted international conventions, declarations and agreements applicable to the Sami as a minority and indigenous people including:[74]

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Right (1966). Article 27 protects minorities, and indigenous peoples, against discrimination: "In those states in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities, shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religion, or use their own language."

- ILO Convention No. 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (1989). The convention states that rights for the indigenous peoples to land and natural resources are recognized as central for their material and cultural survival. In addition, indigenous peoples should be entitled to exercise control over, and manage, their own institutions, ways of life and economic development in order to maintain and develop their identities, languages and religions, within the framework of the states in which they live.

- The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965).

- The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989).

- The UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979).

- The Council of Europe's Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (1995).

- The Council of Europe's Charter for Regional and Minority Languages (1992).

- The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007).[75]

In 2007, the Norwegian Parliament passed the new Reindeer Herding Act acknowledging siida as the basic institution regarding land rights, organization, and daily herding management.[22]

Sweden

The Sametingslag was established as the Swedish Sami Parliament as of 1 January 1993. Sweden recognised the existence of the "Sami nation" in 1989, but the ILO Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, C169 has not been adopted. All indigenous rights are currently banned.

The Compulsory School Ordinance states that Sami pupils are entitled to be taught in their native language; however, a municipality is obliged to arrange mother-tongue teaching in Sami only if a suitable teacher is available and the pupil has a basic knowledge of Sami.[76]

In 2010, after 14 years of negotiation, Laponiatjuottjudus, an association with Sami majority control, will govern the UNESCO World Heritage Site Laponia. The reindeer-herding law will apply in the area as well.[77]

In 1998, Sweden formally apologized for the wrongs committed against the Sami.

Sami is one of five national minority languages recognized by Swedish law.[78]

Finland

The act establishing the Finnish Sami Parliament (Finnish: Saamelaiskäräjät) was passed on November 9, 1973. Finland recognized the Sami as a "people" in 1995, but they have yet to ratify ILO Convention 169 Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples.

Finland ratified the 1966 U.N. Covenant on Civil and Political Rights though several cases brought before the U.N. Human Rights Committee. Of those, 36 cases involved a determination of the rights of individual Sami in Finland and Sweden. The committee decisions clarify that Sami are members of a minority within the meaning of Article 27 and that deprivation or erosion of their rights to practice traditional activities that are an essential element of their culture do come within the scope of Article 27.[79] The case of J. Lansman versus Finland concerned a challenge by Sami reindeer herders in northern Finland to the Finnish Central Forestry Board's plans to approve logging and construction of roads in an area used by the herdsmen as winter pasture and spring calving grounds.[80]

Finland Sami have had access to Sami language instruction in some schools since the 1970s, and language rights were established in 1992. There are three Sami languages spoken in Finland: North Sami, Skolt Sami and Inari Sami. Of these languages, Inari Sami, which is spoken by about 350 speakers, is the only one that is used entirely within the borders of Finland, mainly in the municipality of Inari.

Finland has denied any aboriginal rights or land rights to the Sami people;[81] in Finland, non-Sami can herd reindeer.

Sami people have had very little representation in Finnish national politics. In fact, as of 2007, Janne Seurujärvi, a Finnish Centre Party representative, was the first Sami ever to be elected to the Finnish Parliament.[82]

Russia

Russia has not adopted the ILO Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, C169. The inhabitants of the Kola tundra were forcibly relocated to kolkhoz'es (collective communities) by the state;[83] most Saami are in one kolkhoz at Lujávri (Lovozero).

The 1822 Statute of Administration of Non-Russians in Siberia asserted state ownership over all the land in Siberia and then "granted" possessory rights to the natives.[80][84] Governance of indigenous groups, and especially collection of taxes from them, necessitated protection of indigenous peoples against exploitation by traders and settlers.[80]

The 1993 Constitution, Article 69 states, "The Russian Federation guarantees the rights of small indigenous peoples in accordance with the generally accepted principles and standards of international law and international treaties of the Russian Federation."[80][85] For the first time in Russia, the rights of indigenous minorities were established in the 1993 Constitution.[80]

The Russian Federation ratified the 1966 U.N. Covenant on Civil and Political Rights;[80] Section 2 explicitly forbids depriving a people of "its own means of subsistence."[80] The Russian parliament (Duma) has adopted partial measures to implement it.[80]

The Russian Federation lists distinct indigenous peoples as having special rights and protections under the Constitution and federal laws and decrees.[80][86] These rights are linked to the category known since Soviet times as the malochislennye narody ("small-numbered peoples"), a term that is often translated as "indigenous minorities", which include Arctic peoples such as the Sami, Nenets, Evenki, and Chukchi.[80]

In April 1999, the Russian Duma passed a law that guarantees socio-economic and cultural development to all indigenous minorities, protecting traditional living places and acknowledging some form of limited ownership of territories that have traditionally been used for hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering activities. The law, however, does not anticipate the transfer of title in fee simply to indigenous minorities. The law does not recognize development rights, some proprietary rights including compensation for damage to the property, and limited exclusionary rights. It is not clear, however, whether protection of nature in the traditional places of inhabitation implies a right to exclude conflicting uses that are destructive to nature or whether they have the right to veto development.[80]

The Russian Federation's Land Code reinforces the rights of numerically small peoples ("indigenous minorities") to use places they inhabit and to continue traditional economic activities without being charged rent.[80][87] Such lands cannot be allocated for unrelated activities (which might include oil, gas, and mineral development or tourism) without the consent of the indigenous peoples. Furthermore, indigenous minorities and ethnic groups are allowed to use environmentally protected lands and lands set aside as nature preserves to engage in their traditional modes of land use.[80]

Regional law, Code of the Murmansk Oblast, calls on the organs of state power of the oblast to facilitate the native peoples of the Kola North, specifically naming the Sami, "in realization of their rights for preservation and development of their native language, national culture, traditions and customs." The third section of Article 21 states: "In historically established areas of habitation, Sami enjoy the rights for traditional use of nature and [traditional] activities."[80]

Throughout the Russian North, indigenous and local people are being denied rights to fish, hunt, use pastureland, or exercise control over resources upon which they and their ancestors have depended for centuries. The failure to protect indigenous ways, however, stems not from inadequacy of the written law, but rather from the failure to implement existing laws. Unfortunately, violations of the rights of indigenous peoples continue, and oil, gas, and mineral development and other activities (mining, timber cutting, commercial fishing, and tourism) that bring foreign currency into the Russian economy prevail over the rule of law.[80]

The life ways and economy of indigenous peoples of the Russian North are based upon reindeer herding, fishing, terrestrial and sea mammal hunting, and trapping. Many groups in the Russian Arctic are semi-nomadic, moving seasonally to different hunting and fishing camps. These groups depend upon different types of environment at differing times of the year, rather than upon exploiting a single commodity to exhaustion.[80][88] Throughout northwestern Siberia, oil and gas development has disturbed pastureland and undermined the ability of indigenous peoples to continue hunting, fishing, trapping, and herding activities. Roads constructed in connection with oil and gas exploration and development destroy and degrade pastureland,[89] ancestral burial grounds, and sacred sites and increase hunting by oil workers on the territory used by indigenous peoples.[90]

In the Sami homeland on the Kola Peninsula in northwestern Russia, regional authorities closed a fifty-mile (eighty-kilometer) stretch of the Ponoi River (and other rivers) to local fishing and granted exclusive fishing rights to a commercial company offering catch-and-release fishing to sport fishers largely from abroad.[91] This deprived the local Sami (see Article 21 of the Code of the Murmansk Oblast) of food for their families and community and of their traditional economic livelihood. Thus, closing the fishery to locals may have violated the test articulated by the U.N. Human Rights Committee and disregarded the Land Code, other legislative acts, and the 1992 Presidential decree. Sami are not only forbidden to fish in the eighty-kilometer stretch leased to the Ponoi River Company but are also required by regional laws to pay for licenses to catch a limited number of fish outside the lease area. Residents of remote communities have neither the power nor the resources to demand enforcement of their rights. Here and elsewhere in the circumpolar north, the failure to apply laws for the protection of indigenous peoples leads to "criminalization" of local indigenous populations who cannot survive without "poaching" resources that should be accessible to them legally.[80]

Although indigenous leaders in Russia have occasionally asserted indigenous rights to land and resources, to date there has been no serious or sustained discussion of indigenous group rights to ownership of land.[80]

Nordic

On 16 November 2005 in Helsinki, a group of experts, led by former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Norway Professor Carsten Smith, submitted a proposal for a Nordic Sami Convention to the annual joint meeting of the ministers responsible for Sami affairs in Finland, Norway and Sweden and the presidents of the three Sami Parliaments from the respective countries. This convention recognizes the Sami as one indigenous people residing across national borders in all three countries. A set of minimum standards is proposed for the rights of developing the Sami language and culture and rights to land and water, livelihoods and society.[92] The convention has not yet been ratified in the Nordic countries.[93]

Sami culture

To make up for past suppression, the authorities of Norway, Sweden and Finland now make an effort to build up Sami cultural institutions and promote Sami culture and language.

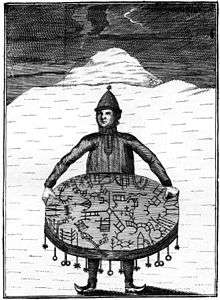

Duodji (craft)

Duodji, the Sami handicraft, originates from the time when the Samis were self-supporting nomads, believing therefore that an object should first and foremost serve a purpose rather than being primarily decorative. Men mostly use wood, bone, and antlers to make items such as antler-handled scrimshawed sami knives, drums, and guksi (burl cups). Women used leather and roots to make items such as gákti (clothing), and birch- and spruce-root woven baskets.

Clothing

Gakti are the traditional clothing worn by the Sámi people. The gákti is worn both in ceremonial contexts and while working, particularly when herding reindeer.

Traditionally, the gákti was made from reindeer leather and sinews, but nowadays, it is more common to use wool, cotton, or silk. Women's gákti typically consist of a dress, a fringed shawl that is fastened with 1–3 silver brooches, and boots/shoes made of reindeer fur or leather. Boots can have pointed or curled toes and often have band-woven ankle wraps. Eastern Sami boots have a rounded toe on reindeer-fur boots, lined with felt and with beaded details. There are different gákti for women and men; men's gákti have a shorter "jacket-skirt" than a women's long dress. Traditional gákti are most commonly in variations of red, blue, green, white, medium-brown tanned leather, or reindeer fur. In winter, there is the addition of a reindeer fur coat and leggings, and sometimes a poncho (luhkka) and rope/lasso.

The colours, patterns and the jewellery of the gákti indicate where a person is from, if a person is single or married, and sometimes can even be specific to their family. The collar, sleeves and hem usually have appliqués in the form of geometric shapes. Some regions have ribbonwork, others have tin embroidery, and some Eastern Sami have beading on clothing or collar. Hats vary by gender, season, and region. They can be wool, leather, or fur. They can be embroidered, or in the East, they are more like a beaded cloth crown with a shawl. Some traditional shamanic headgear had animal hides, plaits, and feathers, particularly in East Sapmi.

The gákti can be worn with a belt; these are sometimes band-woven belts, woven, or beaded. Leather belts can have scrimshawed antler buttons, silver concho-like buttons, tassles, or brass/copper details such as rings. Belts can also have beaded leather pouches, antler needle cases, accessories for a fire, copper rings, amulets, and often a carved and/or scrimshawed antler handled knife. Some Eastern Sami also have a hooded jumper (малиц) from reindeer skins with wool inside and above the knee boots.

Media and literature

- There are short daily news bulletins in Northern Sámi on national TV in Norway, Sweden and Finland. Children's television shows in Sami are also frequently made. There is also a radio station for Northern Sámi, which has some news programs in the other Sámi languages.

- A single daily newspaper is published in Northern Sami, Ávvir,[94] along with a few magazines.

- There is a Sámi theatre, Beaivvaš, in Kautokeino on the Norwegian side, as well as in Kiruna on the Swedish side. Both tour the entire Sámi area with drama written by Sámi authors or international translations.

- A number of novels and poetry collections are published every year in Northern Sámi, and sometimes in the other Sámi languages as well. The largest Sami Publishing house is Davvi Girji.

.jpg)

Music

A characteristic feature of Sami musical tradition is the singing of yoik. Yoiks are song-chants and are traditionally sung a cappella, usually sung slowly and deep in the throat with apparent emotional content of sorrow or anger. Yoiks can be dedicated to animals and birds in nature, special people or special occasions, and they can be joyous, sad or melancholic. They often are based on syllablic improvisation. In recent years, musical instruments frequently accompany yoiks. The only traditional Sami instruments that were sometimes used to accompany yoik are the "fadno" flute (made from reed-like Angelica archangelica stems) and hand drums (frame drums and bowl drums).

Education

- Education with Sami as the first language is available in all four countries, and also outside the Sami area.

- Sami University College is located in Kautokeino. Sami language is studied in several universities in all countries, most notably the University of Tromsø, which considers Sami a mother tongue, not a foreign language.

Festivals and markets

- Numerous Sami festivals throughout the Sápmi area celebrate different aspects of the Sami culture. The best-known on the Norwegian side is Riddu Riđđu, though there are others, such as Ijahis Idja in Inari. Among the most festive are the Easter festivals taking place in Kautokeino and Karasjok prior to the springtime reindeer migration to the coast. These festivals combine traditional culture with modern phenomena such as snowmobile races.

Visual arts

In addition to Duodji (Sami handicraft), there is a developing area of contemporary Sami visual art. Galleries such as Sámi Dáiddaguovddáš (Sami Center for Contemporary Art)[95] are being established.

Dance

For many years there was a misconception that the Sámi were the only Indigenous people without a dance tradition in the world.[96] Sami dance companies have emerged such as Kompani Nomad.[97] A book about the "lost" Sami dance tradition called Jakten på den försvunna samiska dansen was recently published by Umeå University's Centre for Sami Research (CeSam).[98] In the eastern areas of Sápmi the dance tradition has been more continuous and is continued by groups such as Johtti Kompani.[99]

Reindeer husbandry

Reindeer husbandry has been and still is an important aspect of Sami culture. During the years of forced assimilation, the areas in which reindeer herding was an important livelihood were among the few where the Sami culture and language survived.

Today in Norway and Sweden, reindeer husbandry is legally protected as an exclusive Sami livelihood, such that only persons of Sami descent with a linkage to a reindeer herding family can own, and hence make a living off, reindeer. Presently, about 2,800 people are engaged in reindeer herding in Norway.[8] In Finland, reindeer husbandry is not exclusive and is practiced to a limited degree also by ethnic Finns. Legally, it is restricted to EU/EEA nationals resident in the area. In the north (Lapland), it plays a major role in the local economy, while its economic impact is lesser in the southern parts of the area (Province of Oulu).

Among the reindeer herders in Sami villages, the women usually have a higher level of formal education in the area.[100]

Games

The Sámi have traditionally played both card games and board games, but few Sámi games have survived, in part because Christian missionaries and Laestadianists considered such games sinful.[101] Only the rules of three Sámi board games have been preserved into modern times. Sáhkku is a running-fight board game where each player controls a set of soldiers (referred to as "women" and "men") that races across a board in a loop, attempting to eliminate the other player's soldiers. The game is related to South Scandinavian daldøs, Arabian tâb and Indian tablan.[102] Sáhkku differs from these games in several respects, most notably the addition of a piece - "the king" - that changes gameplay radically. Tablut is a pure strategy game in the tafl family. The game features "Swedes" and a "Swedish king" whose goal is to escape, and an army of "Muscovites" whose goal is to capture the king. Tablut is the only tafl game where a relatively intact set of rules have survived into our time. Hence, all modern versions of tafl (commonly called "Hnefatafl" and marketed exclusively as "Norse" or "Viking" games) are based on the Sámi game of tablut.[103] Dablot Prejjesne is a game related to alquerque which differs from most such games (e.g. draughts) by having pieces of three different ranks. The game's two sides are referred to as "Sámi" (king, prince, warriors) and "Finlenders" (landowners, landowner's son, farmers).[104]

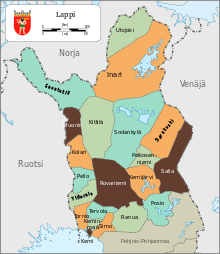

Sápmi

Sápmi is the name of the cultural region traditionally inhabited by the Sami people. Non-Sami and many regional maps have often called this same region Lapland as there is considerable regional overlap between the two terms. The overlap is, however, not complete: Lapland (Finnish Lappi, Swedish Lappland) covers only some of those parts of Sápmi that have fallen under Finnish and Swedish jurisdiction and none of those that have fallen under Norwegian or Russian. Thus, the larger part of Sápmi is not covered by the term "Lapland". Lapland can also be either misleading or offensive, or both, depending on the context and where this word is used, to the Sami. Among the Sami people, Sápmi is strictly used and acceptable.

Sápmi is located in Northern Europe, includes the northern parts of Fennoscandia and spans four countries: Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia.

Area

There is no official geographic definition for the boundaries of Sápmi. However, the following counties and provinces are usually included:

- Dalarnas Län county in Sweden

- Finnmark county in Norway

- Jämtlands Län county in Sweden

- Lapland Region in Finland

- Murmansk oblast in Russia

- Nord-Trøndelag county in Norway

- Nordland county in Norway

- Norrbottens Län county in Sweden

- Troms county in Norway

- Västerbottens Län county in Sweden

The municipalities of Gällivare, Jokkmokk and Arjeplog in Swedish Lappland were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996 as a "Laponian Area".

The Sami Domicile Area in Finland consists of the municipalities of Enontekiö, Utsjoki and Inari as well as a part of the municipality of Sodankylä.

Important Sami towns

The following towns and villages have a significant Sami population or host Sami institutions (Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish or Russian name in parentheses):

- Aanaar, Anár, or Aanar (Inari), is the location of the Finnish Sami Parliament, Sajos Sámi Cultural Centre, SAKK - Saamelaisalueen koulutuskeskus (Sámi Education Institute), Anarâškielâ servi (Inari Sámi Language Association), and the Inari Sami Siida Museum.

- Aarborte (Hattfjelldal) is a southern Sami center with a Southern Sami-language school and a Sami culture center.

- Árjepluovve (Arjeplog) is the Pite Saami center in Sweden.

- Deatnu (Tana) has a significant Sami population.

- Divtasvuodna (Tysfjord) is a center for the Lule-Sami population. The Árran Lule-Sami center is located here.

- Gáivuotna (Kåfjord, Troms) is an important center for the Sea-Sami culture. Each summer the Riddu Riđđu festival is held in Gáivuotna. The municipality has a Sami-language center and hosts the Ája Sami Center. The opposition against Sami language and culture revitalization in Gáivuotna was infamous in the late 1990s and included Sami-language road signs being shot to pieces repeatedly.[105]

- Giron (Kiruna), proposed seat of the Swedish Sami Parliament.

- Guovdageaidnu (Kautokeino) is perhaps the cultural capital of the Sami. About 90% of the population speaks Sami. Several Sami institutions are located in Kautokeino including: Beaivváš Sámi Theatre, a Sami high school and reindeer-herding School, the Sami University College, the Nordic Sami Research Institute, the Sami Language Board, the Resource Centre for the Rights of Indigenous People, and the International Centre for Reindeer Husbandry. In addition, several Sami media are located in Kautokeino including the Sami-language Áššu newspaper, and the DAT Sami publishing house and record company. Kautokeino also hosts the Sami Easter Festival, which includes the Sami Grand Prix 2010 (Sami Musicfestival) and the Reindeer Racing World Cup. The Kautokeino rebellion in 1852 is one of the few Sami rebellions against the Norwegian government's oppression against the Sami.

- Iänudâh, or Eanodat (Enontekiö).

- Jiellevárri, or Váhčir (Gällivare)

- Jåhkåmåhkke (Jokkmokk) holds a Sami market on the first weekend of every February and has a Sami school for language and traditional knowledge called Samij Åhpadusguovdásj.

- Kárášjohka (Karasjok) is the seat of the Norwegian Sami Parliament. Other important Sami institutions are located in Kárášjohka, including NRK Sami Radio, the Sami Collections museum, the Sami Art Centre, the Sami Specialist Library, the Mid-Finnmark legal office, a child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic - one of few on a national level approved for providing full specialist training. Other significant institutions include a Sami Specialist Medical Centre, and the Sami Health Research Institute.[106] In addition, the Sápmi cultural park is in the township, and the Sami-language Min Áigi newspaper is published here.

- Leavdnja (Lakselv) in Porsáŋgu (Porsanger) municipality is the location of the Finnmark Estate and the Ságat Sami newspaper. The Finnmarkseiendommen organization owns and manages about 95% of the land in Finnmark, and 50% of its board members are elected by the Norwegian Sami Parliament.

- Луя̄ввьр (Lovozero)

- Luvlieluspie (Östersund) is the center for the Southern Sami people living in Sweden. It is the site for Gaaltije – centre for South Sami culture – a living source of knowledge for South Sami culture, history and business. Luvlieluspie also hosts the Sami Information Centre and one of the offices to the Sami Parliament in Sweden.

- Njauddâm is the center for the Skolt Sami of Norway, which have their own museum in the town.

- Ohcejohka (Utsjoki).

- Snåase (Snåsa) is a center for the Southern Sami language and the only municipality in Norway where Southern Sami is an official language. The Saemien Sijte Southern Sami museum is located in Snåase.

- Unjárga (Nesseby) is an important center for the Sea Sami culture. It is also the site for the Várjjat Sámi Museum and the Norwegian Sami Parliament's department of culture and environment. The first Sami to be elected into the Norwegian Parliament, Isak Saba, was born there.

- Árviesjávrrie (Arvidsjaur). New settlers from the south of Sweden didn't arrive until the second half of the 18th century. Because of that, Sami tradition and culture has been well preserved. Sami people living in the south of Norrbotten, Sweden, use the city for Reindeer herding during the summer. During winter they move the Reindeers to the coast, to Piteå.

Demographics

In the geographical area of Sápmi, the Sami are a small population. According to some, the estimated total Sami population is about 70,000.[107] One problem when attempting to count the population of the Sámi is that there are few common criteria of what "being a Sámi" constitutes. In addition, there are several Sámi languages and additional dialects, and there are several areas in Sapmi where few of the Sami speak their native language due to the forced cultural assimilation, but still consider themselves Sami. Other identity markers are kinship (which can be said to, at some level or other, be of high importance for all Sámi), the geographical region of Sápmi where their family came from, and/or protecting or preserving certain aspects of Sami culture.[108]

All the Nordic Sámi Parliaments have included as the "core" criterion for registering as a Sámi the identity in itself—one must declare that one truly considers oneself a Sámi. Objective criteria vary, but are generally related to kinship and/or language.

Still, due to the cultural assimilation of the Sami people that had occurred in the four countries over the centuries, population estimates are difficult to measure precisely.[109] The population has been estimated to be between 80,000 and 135,000[110][111] across the whole Nordic region, including urban areas such as Oslo, Norway, traditionally considered outside Sápmi. The Norwegian state recognizes any Norwegian as Sámi if he or she has one great-grandparent whose home language was Sámi, but there is not, and has never been, any registration of the home language spoken by Norwegian people.

Roughly half of all Sámi live in Norway, but many live in Sweden, with smaller groups living in the far north of Finland and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. The Sámi in Russia were forced by the Soviet authorities to relocate to a collective called Lovozero/Lujávri, in the central part of the Kola Peninsula.

Sami groups and languages

American scientist Michael E. Krauss published in 1997 an estimate of Sami population and their languages.[112][113]

| Group | Population | Language group | Language | Speakers | % | Most important territory | Other traditional territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Sami | 42 500 | Western Sami languages | Northern Sami language | 21 700 | 51% | Norway | Sweden, Finland |

| Lule Sami | 8 000 | Western Sami languages | Lule Sami language | 2 300 | 29% | Sweden | Norway |

| Pite Sami | 2 000 | Western Sami languages | Pite Sami language | 60 | 3% | Sweden | Norway |

| Southern Sami | 1 200 | Western Sami languages | Southern Sami language | 600 | 50% | Sweden | Norway |

| Ume Sami | 1 000 | Western Sami languages | Ume Sami language | 50 | 5% | Sweden | Norway |

| Skolt Sami | 1 000 | Eastern Sami languages | Skolt Sami language | 430 | 43% | Finland | Russia, Norway |

| Kildin Sami | 1 000 | Eastern Sami languages | Kildin Sami language | 650 | 65% | Russia | |

| Inari Sami | 900 | Eastern Sami languages | Inari Sami language | 300 | 33% | Finland | |

| Ter Sami | 400 | Eastern Sami languages | Ter Sami language | 8 | 2% | Russia | |

| Akkala Sami | 100 | Eastern Sami languages | Akkala Sami language | 7 | 7% | Russia | |

| Sami | 58 100 | Sami languages | Sami languages | 26 105 | 45% | Norway | Sweden, Finland, Russia |

- Southern Sami

- Ume Sami

- Pite Sami

- Lule Sami

- Northern Sami

- Skolt Sami

- Inari Sami

- Kildin Sami

- Ter Sami

UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger gives different estimated numbers of speakers of each language:[114]

- Northern Sami language (Davvisámegiella): 30,000 (definitely endangered)

- Lule Sami language (Julevsámegiella): 2,000 (severely endangered)

- Kildin Sami language (Кīlt sam' kīll): 787 (severely endangered)

- Southern Sami language (Åarjelsaemien gïele): 500 (severely endangered)

- Skolt Sami language (Nuõrttsää'mǩiõll): 300 (severely endangered)

- Inari Sami language (Anarâškielâ): 400 (severely endangered)

- Ume Sami language (Ubmejensámiengiella): 20 (critically endangered)

- Pite Sami language (Bidumsámegiella): 20 (critically endangered)

- Ter Sami language (Ter saa'me kiill): 2 (critically endangered)

- Akkala Sami language: 0 (extinct)

Kemi Sami language became extinct in the 19th century.

Many Sami do not speak any of the Sami languages any more due to historical assimilation policies, so the number of Sami living in each area is much higher.

As with many indigenous languages,[115] all Sami languages are at some degree of endangerment, ranging from what UNESCO defines as "definitely endangered" to "extinct".[114]

Division by geography

Sápmi is traditionally divided into:

- Eastern Sapmi (Inari, Skolt, Akkala, Kildin and Teri Sami in Kola peninsula (Russia) and Inari (Finland, formerly also in eastern Norway)

- Northern Sápmi (Northern, Lule and Pite Sami in most of northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland)

- Southern Sápmi (Ume and Southern Sami in central parts of Sweden and Norway)

It should also be noted that many Sami now live outside Sápmi, in large cities such as Oslo in Norway.

Division by occupation

A division often used in Northern Sami is based on occupation and the area of living. This division is also used in many historical texts:[116]

- Reindeer Sami or Mountain Sami (in Northern Sami boazosapmelash or badjeolmmosh). Previously nomadic Sami living as reindeer herders. Now most have a permanent residence in the Sami core areas. Some 10% of Sami practice reindeer herding, which is seen as a fundamental part of a Sami culture and, in some parts of the Nordic countries, can be practiced by Samis only.

- Sea Sami (in Northern Sami mearasapmelash). These lived traditionally by combining fishing and small-scale farming. Today, often used for all Sami from the coast regardless of their occupation.

- Forest Sami who traditionally lived by combining fishing in inland rivers and lakes with small-scale reindeer-herding.

- City Sami who are now probably the largest group of Sami.

Division by country

According to the Norwegian Sami Parliament, the Sami population of Norway is 40,000. If all people who speak Sami or have a parent, grandparent, or great-grandparent who speaks or spoke Sami are included, the number reaches 70,000. As of 2005, 12,538 people were registered to vote in the election for the Sami Parliament in Norway. The bulk of the Sami live in Finnmark and Northern Troms, but there are also Sami populations in Southern Troms, Nordland and Trøndelag. Due to recent migration, it has also been claimed that Oslo is the municipality with the largest Sami population. The Sami are in a majority only in the municipalities of Guovdageaidnu-Kautokeino, Karasjohka-Karasjok, Porsanger, Deatnu-Tana and Unjargga-Nesseby in Finnmark, and Gáivuotna (Kåfjord) in Northern Troms. This area is also known as the Sami core area. Sami and Norwegian are equal as administrative languages in this area.

In Sweden and Norway, Sami are primarily Lutheran, in Finland and Russia they are orthodox Christians.

According to the Swedish Sami Parliament, the Sami population of Sweden is about 20,000.

According to the Finnish Population Registry Center and the Finnish Sami Parliament, the Sami population living in Finland was 7,371 in 2003.[117] As of 31 December 2006, only 1776 of them had registered to speak one of the Sami languages as the mother tongue.[118]

According to the 2002 census, the Sami population of Russia was 1,991.

Since 1926, the number of identified Sami in Russia has gradually increased:

- Census 1926: 1,720 (this number refers to the entire Soviet Union)

- Census 1939: 1,829

- Census 1959: 1,760

- Census 1970: 1,836

- Census 1979: 1,775

- Census 1989: 1,835

- Census 2002: 1,991

Sami immigration outside of Sapmi

There are an estimated 30,000 people living in North America who are either Sami, or descendants of Sami.[119] Most have settled in areas that are known to have Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish immigrants. Some of these concentrated areas are Minnesota, North Dakota, Iowa, Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Illinois, California, Washington, Utah and Alaska; and throughout Canada, including Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Northern Ontario, and the Canadian territories of the Northwest Territories, Yukon, and the territory now known as Nunavut.

Descendants of these Sami immigrants typically know little of their heritage because their ancestors purposely hid their indigenous culture to avoid discrimination from the dominating Scandinavian or Nordic culture. Though some of these Sami are diaspora that moved to North America in order to escape assimilation policies in their home countries, many continued to downplay their Sami culture in an internalization of colonial viewpoints about indigenous peoples and in order for them to try to blend into their respective Nordic cultures. There were also several Sami families that were brought to North America with herds of reindeer by the U.S. and Canadian governments as part of the "Reindeer Project" designed to teach the Inuit about reindeer herding.[120] There is a long history of Sami in Alaska.

Some of these Sami immigrants and descendants of immigrants are members of the Sami Siida of North America.

Organization

Sápmi demonstrates a distinct semi-national identity that transcends the borders between Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. There is no movement for complete autonomy.

Sami Parliaments

The Sami Parliaments (Sámediggi in Northern Sami, Sämitigge in Inari Sami, Sää'mte'ǧǧ in Skolt Sami) founded in Finland (1973), Norway (1989) and Sweden (1993) are the representative bodies for peoples of Sami heritage. Russia has not recognized the Sami as a minority and, as a result, recognizes no Sami parliament, even if the Sami people there have formed an unrecognised Sami Parliament of Russia. There is no single, unified Sami parliament that spans across the Nordic countries. Rather, each of the aforementioned three countries has set up its own separate legislatures for Sami people, even though the three Sami Parliaments often work together on cross-border issues. In all three countries, they act as an institution of cultural autonomy for the indigenous Sami people. The parliaments have very weak political influence, far from autonomy. They are formally public authorities, ruled by the Scandinavian governments, but have democratically elected parliamentarians, whose mission is to work for the Sami people and culture. Candidates' election promises often get into conflict with the institutions' submission under their governments, but as authorities, they have some influence over the government.

Norwegian organizations

The main organisations for Sami representation in Norway are the siidas. They cover northern and central Norway.

Swedish organizations

The main organisations for Sami representation in Sweden are the siidas. They cover northern and central Sweden.

Finnish organizations

In contrast to Norway and Sweden, in Finland, a siida (paliskunta in Finnish) is a reindeer-herding corporation that is not restricted by ethnicity. There are indeed some ethnic Finns who practice reindeer herding, and in principle, all residents of the reindeer herding area (most of Finnish Lapland and parts of Oulu province) who are citizens of EEA countries,[121] i.e., the European Union and Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, are allowed to join a paliskunta.

Russian organizations

In 2010, the Sami Council supported the establishment of a cultural center in Russia for Arctic peoples. The Center for Northern Peoples aims to promote artistic and cultural cooperation between the Arctic peoples of Russia and the Nordic countries, with particular focus on indigenous peoples and minorities.[122]

Border conflicts

Sápmi, the Sami traditional lands, cross four national borders. Traditional summer and winter pastures sometimes lie on different sides of the borders of the nation-states. In addition to that, there is a border drawn for modern-day Sápmi. Some state that the rights (for reindeer herding and, in some parts, even for fishing and hunting) include not only modern Sápmi but areas that are beyond today's Sápmi that reflect older territories. Today's "borders" originate from the 14th to 16th centuries when land-owning conflicts occurred. The establishment of more stable dwelling places and larger towns originates from the 16th century and was performed for strategic defence and economic reasons, both by peoples from Sami groups themselves and more southern immigrants.

Owning land within the borders or being a member of a siida (Sami corporation) gives rights. A different law enacted in Sweden in the mid-1990s gave the right to anyone to fish and hunt in the region, something that was met with skepticism and anger amongst the siidas.

Court proceedings have been common throughout history, and the aim from the Sami viewpoint is to reclaim territories used earlier in history. Due to a major defeat in 1996, one siida has introduced a sponsorship "Reindeer Godfather" concept to raise funds for further battles in courts. These "internal conflicts" are usually conflicts between non-Sami land owners and reindeer owners. Cases question the Sami ancient rights to reindeer pastures. In 2010, Sweden was criticized for its relations with the Sami in the Universal Periodic Review conducted by the Working Group of the Human Rights Council.[123]

The question whether the fjeld's territory is owned by the governments (crown land) or by the Sami population is not answered.

From an indigenous perspective, people "belong to the land", the land does not belong to people, but this does not mean that hunters, herders, and fishing people do not know where the borders of their territories are located as well as those of their neighbors.[80]

National symbols

Although the Sami have considered themselves to be one people throughout history, the idea of Sápmi, a Sami nation, first gained acceptance among the Sami in the 1970s, and even later among the majority population. During the 1980s and 1990s, a flag was created, a national song was written, and the date of a national day was settled.

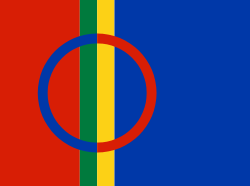

Flag

The Sami flag was inaugurated during the Sami Conference in Åre, Sweden, on 15 August 1986. It was the result of a competition for which many suggestions were entered. The winning design was submitted by the artist Astrid Båhl from Skibotn, Norway.

The motif (shown right) was derived from the shaman's drum and the poem "Paiven parneh" ("Sons of the Sun") by the South Sami Anders Fjellner describing the Sami as sons and daughters of the sun. The flag has the Sami colours, red, green, yellow and blue, and the circle represents the sun (red) and the moon (blue).

The Sami People's Day

The Sami National Day falls on February 6 as this date was when the first Sami congress was held in 1917 in Trondheim, Norway. This congress was the first time that Norwegian and Swedish Sami came together across their national borders to work together to find solutions for common problems. The resolution for celebrating on 6 February was passed in 1992 at the 15th Sami congress in Helsinki. Since 1993, Norway, Sweden and Finland have recognized February 6 as Sami National Day.

"Song of the Sami People"

"Sámi soga lávlla" ("Song of the Sami People", lit. "Song of the Sami Family") was originally a poem written by Isak Saba that was published in the newspaper Sagai Muittalægje for the first time on 1 April 1906. In August 1986, it became the national anthem of the Sami. Arne Sørli set the poem to music, which was then approved at the 15th Sami Conference in Helsinki in 1992. "Sámi soga lávlla" has been translated into all of the Sami languages.

Religion

Widespread Shamanism persisted among the Sami up until the 18th century. Most Sami today belong to the state-run Lutheran churches of Norway, Sweden and Finland. Some Sami in Russia belong to the Russian Orthodox Church, and similarly, some Skolt Sami resettled in Finland are also part of an Eastern Orthodox congregation, with an additional small population in Norway.

Traditional Sami religion

Traditional Sami religion was a type of polytheism. (See Sami deities.) There was some diversity due to the wide area that is Sápmi, allowing for the evolution of variations in beliefs and practices between tribes. The old beliefs are closely connected to the land, animism, and the supernatural. Sami spirituality is often characterized by pantheism, a strong emphasis on the importance of personal spirituality and its interconnectivity with one's own daily life, and a deep connection between the natural and spiritual "worlds".[124] Among other roles, the Sami Shaman, or noaidi, enabled ritual communication with the supernatural[125] through the use of tools such as drums, chants, and sacred objects.[126] Some practices within the Old Sami religion included natural sacred sites such as mountains, springs, land formations, as well as man-made ones such as petroglyphs and labyrinths.[127]

Sami religion shared some elements with Norse mythology, possibly from early contacts with trading Vikings (or vice versa). Through a mainly French initiative from Joseph Paul Gaimard as part of his La Recherche Expedition, Lars Levi Læstadius began research on Sami mythology. His work resulted in Fragments of Lappish Mythology, since by his own admission, they contained only a small percentage of what had existed. The fragments were termed Theory of Gods, Theory of Sacrifice, Theory of Prophecy, or short reports about rumorous Sami magic and Sami sagas. Generally, he claims to have filtered out the Norse influence and derived common elements between the South, North, and Eastern Sami groups. The mythology has common elements with other traditional indigenous religions as well—such as those in Siberia and North America.

Missionary efforts

The term Sami religion usually refers to the traditional religion, practiced by most Sámi until approximately the 18th century. Christianity was introduced by Roman Catholic missionaries as early as the 13th century. Increased pressure came after the Protestant Reformation, and rune drums were burned or sent to museums abroad. In this period, many Sami practiced their traditional religion at home, while going to church on Sunday. Since the Sami were considered to possess "witchcraft" powers, they were often accused of sorcery during the 17th century and were the subjects of witchcraft trials and burnings.[128]

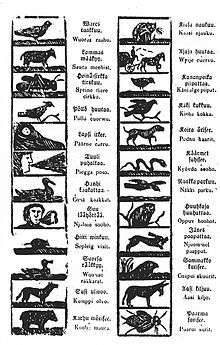

In Norway, a major effort to convert the Sami was made around 1720, when Thomas von Westen, the "Apostle of the Sami", burned drums, burned sacred objects, and converted people.[129] Out of the estimated thousands of drums prior to this period, only about 70 are known to remain today, scattered in museums around Europe.[126] Sacred sites were destroyed, such as sieidi (stones in natural or human-built formations), álda and sáivu (sacred hills), springs, caves and other natural formations where offerings were made.

In the far east of the Sami area, the Russian monk Trifon converted the Sami in the 16th century. Today, St. George's chapel in Neiden, Norway (1565), testifies to this effort.

Laestadius

Around 1840 Swedish Sami Lutheran pastor and administrator Lars Levi Laestadius initiated among the Sami a puritanical pietist movement emphasizing complete abstinence from alcohol. This movement is still very dominant in Sami-speaking areas. Laestadius spoke many languages, and he became fluent and preached in Finnish and Northern Sami in addition to his native Southern Sami and Swedish,[130] the language he used for scholarly publications.[129]

Two great challenges Laestadius had faced since his early days as a church minister were the indifference of his Sami parishioners, who had been forced by the Swedish government to convert from their shamanistic religion to Lutheranism, and the misery caused them by alcoholism. The spiritual understanding Laestadius acquired and shared in his new sermons "filled with vivid metaphors from the lives of the Sami that they could understand, ... about a God who cared about the lives of the people" had a profound positive effect on both problems. One account from a Sami cultural perspective recalls a new desire among the Sami to learn to read and a "bustle and energy in the church, with people confessing their sins, crying and praying for forgiveness ... [Alcohol abuse] and the theft of [the Samis'] reindeer diminished, which had a positive influence on the Sami's relationships, finances and family life."[131]

Neo-shamanism and traditional healing

Today there are a number of Sami who seek to return to the traditional Pagan values of their ancestors. There are also some Sami who claim to be noaidi and offer their services through newspaper advertisements, in New Age arrangements, or for tourist groups. While they practice a religion based on that of their ancestors, widespread anti-pagan prejudice has caused these shamans to be generally not viewed as part of an unbroken Sami religious tradition. Traditional Sámi beliefs are composed of three intertwining elements: animism, shamanism, and polytheism. Sámi animism is manifested in the Sámi's belief that all significant natural objects (such as animals, plants, rocks, etc.) possess a soul; and from a polytheistic perspective, traditional Sámi beliefs include a multitude of spirits.[129] Many contemporary practitioners are compared to practitioners of neo-paganism, as a number of neopagan religions likewise combine elements of ancient pagan religions with more recent revisions or innovations, but others feel they are attempting to revive or reconstruct indigenous Sami religions as found in historic, folkloric sources and oral traditions.

In 2012, County Governor of Troms approved Shamanic Association of Tromsø as a new religion.[132]

A very different religious idea is represented by the numerous "wise men" and "wise women" found throughout the Sami area. They often offer to heal the sick through rituals and traditional medicines and may also combine traditional elements, such as older Sami teachings, with newer monotheistic inventions that Christian missionaries taught their ancestors, such as readings from the Bible.

Language