SWI/SNF

| SWIB | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

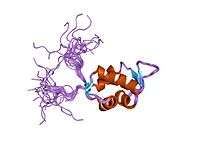

Solution structure of the SWIB/MDM2 domain of the hypothetical protein AT5G14170 from Arabidopsis thaliana | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | SWIB | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02201 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR003121 | ||||||||

| SMART | SWIB | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1ycr | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1ycr | ||||||||

| |||||||||

In molecular biology, SWI/SNF (SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable),[1][2] is a nucleosome remodeling complex found in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. In simpler terms, it is a group of proteins that associate to remodel the way DNA is packaged. It is composed of several proteins – products of the SWI and SNF genes (SWI1, SWI2/SNF2, SWI3, SWI5, SWI6) as well as other polypeptides.[3] It possesses a DNA-stimulated ATPase activity and can destabilise histone-DNA interactions in reconstituted nucleosomes in an ATP-dependent manner, though the exact nature of this structural change is unknown.

The human analogs of SWI/SNF are BAF (SWI/SNF-A) and PBAF (SWI/SNF-B). BAF in turn stands for "BRG1- or HBRM-associated factors", and PBAF is for "polybromo-associated BAF".[4]

Mechanism of action

It has been found that the SWI/SNF complex (in yeast) is capable of altering the position of nucleosomes along DNA.[5] Two mechanisms for nucleosome remodeling by SWI/SNF have been proposed.[6] The first model contends that a unidirectional diffusion of a twist defect within the nucleosomal DNA results in a corkscrew-like propagation of DNA over the octamer surface that initiates at the DNA entry site of the nucleosome. The other is known as the "bulge" or "loop-recapture" mechanism and it involves the dissociation of DNA at the edge of the nucleosome with reassociation of DNA inside the nucleosome, forming a DNA bulge on the octamer surface. The DNA loop would then propagate across the surface of the histone octamer in a wave-like manner, resulting in the repositioning of DNA without changes in the total number of histone-DNA contacts.[7] A recent study[8] has provided strong evidence against the twist diffusion mechanism and has further strengthened the loop-recapture model.

Role as a tumor suppressor

The mammalian SWI/SNF (mSWI/SNF) complex functions as a tumor suppressor in many human malignancies. It was first identified in 1998 as a tumor suppressor in rhabdoid tumors, a rare pediatric malignancy.[9] As DNA sequencing costs diminished, many tumors were sequenced for the first time around 2010. Several of these studies revealed SWI/SNF to be a tumor suppressor in a number of diverse malignancies.[10][11][12][13] A meta-analysis of many sequencing studies demonstrated SWI/SNF to be mutated in approximately 20% of human malignancies.[14]

SWIB/MDM2 protein domain

The protein domain, SWIB/MDM2, short for SWI/SNF complex B/MDM2 is an important domain. This protein domain has been found in both SWI/SNF complex B and in the negative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor MDM2. It has been shown that MDM2 is homologous to the SWIB complex.[15]

Function

The primary function of the SWIB protein domain is to aid gene expression. In yeast, it expresses certain genes, in particular BADH2, GAL1, GAL4, and SUC2. It works by increasing transcription. It has ATPase activity, which means it breaks down ATP, the basic unit of energy currency. This destabilises the interaction between DNA and histones. This disrupts chromatin and opens up the transcription-binding domains. Transcription factors can bind to this site, leading to an increase in transcription.[16]

Protein interaction

The protein interactions of the SWI/SNF complex with the chromatin allows binding of transcription factors and therefore increase in transcription.[16]

Structure

This protein domain is known to contain one short alpha helix.

Family members

Below is a list of yeast SWI/SNF family members and human orthologs:[17]

| yeast | human | function |

|---|---|---|

| SWI1 | ARID1A, ARID1B | contains LXXLL nuclear receptor binding motifs |

| SWI2/SNF2 | SMARCA4 | ATP dependent chromatin remodeling |

| SWI3 | SMARCC1, SMARCC2 | similar sequence, function unknown |

| SWP73 | SMARCD1, SMARCD2, SMARCD3 | similar sequence, function unknown |

| SWP61 | ACTL6A, ACTL6B | actin-like protein |

History

The SWI/SNF complex was first discovered in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. It was named after yeast mating types switching (SWI) and sucrose nonfermenting (SNF).[16]

See also

References

- ↑ Neigeborn L, Carlson M (1984). "Genes Affecting the Regulation of SUC2 Gene Expression by Glucose Repression in SACCHAROMYCES CEREVISIAE". Genetics. 108 (4): 845–58. PMC 1224269

. PMID 6392017.

. PMID 6392017. - ↑ Stern M, Jensen R, Herskowitz I (1984). "Five SWI genes are required for expression of the HO gene in yeast". J. Mol. Biol. 178 (4): 853–68. PMID 6436497. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(84)90315-2.

- ↑ Pazin MJ, Kadonaga JT (1997). "SWI2/SNF2 and related proteins: ATP-driven motors that disrupt protein-DNA interactions?". Cell. 88 (6): 737–40. PMID 9118215. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81918-2.

- ↑ Nie Z, Yan Z, Chen EH, Sechi S, Ling C, Zhou S, Xue Y, Yang D, Murray D, Kanakubo E, Cleary ML, Wang W (April 2003). "Novel SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complexes contain a mixed-lineage leukemia chromosomal translocation partner". Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 (8): 2942–52. PMC 152562

. PMID 12665591. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.8.2942-2952.2003.

. PMID 12665591. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.8.2942-2952.2003. - ↑ Whitehouse I, Flaus A, Cairns BR, White MF, Workman JL, Owen-Hughes T (August 1999). "Nucleosome mobilization catalysed by the yeast SWI/SNF complex". Nature. 400 (6746): 784–7. PMID 10466730. doi:10.1038/23506.

- ↑ van Holde K, Yager T (2003). "Models for chromatin remodeling: a critical comparison". Biochem. Cell Biol. 81 (3): 169–72. PMID 12897850. doi:10.1139/o03-038.

- ↑ Flaus A, Owen-Hughes T (2003). "Mechanisms for nucleosome mobilization". Biopolymers. 68 (4): 563–78. PMID 12666181. doi:10.1002/bip.10323.

- ↑ Zofall M, Persinger J, Kassabov SR, Bartholomew B (2006). "Chromatin remodeling by ISW2 and SWI/SNF requires DNA translocation inside the nucleosome". Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13 (4): 339–46. PMID 16518397. doi:10.1038/nsmb1071.

- ↑ Versteege I, Sévenet N, Lange J, Rousseau-Merck MF, Ambros P, Handgretinger R, Aurias A, Delattre O (July 1998). "Truncating mutations of hSNF5/INI1 in aggressive paediatric cancer". Nature. 394 (6689): 203–6. PMID 9671307. doi:10.1038/28212.

- ↑ Wiegand KC; Shah SP; Al-Agha OM; Zhao Y; Tse K; Zeng T; Senz J; McConechy MK; Anglesio MS; Kalloger SE; Yang W; Heravi-Moussavi A; Giuliany R; Chow C; Fee J; Zayed A; Prentice L; Melnyk N; Turashvili G; Delaney AD; Madore J; Yip S; McPherson AW; Ha G; Bell L; Fereday S; Tam A; Galletta L; Tonin PN; Provencher D; Miller D; Jones SJ; Moore RA; Morin GB; Oloumi A; Boyd N; Aparicio SA; Shih IeM; Mes-Masson AM; Bowtell DD; Hirst M; Gilks B; Marra MA; Huntsman DG (October 2010). "ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas". N. Engl. J. Med. 363 (16): 1532–43. PMC 2976679

. PMID 20942669. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1008433.

. PMID 20942669. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1008433. - ↑ Li M, Zhao H, Zhang X, Wood LD, Anders RA, Choti MA, Pawlik TM, Daniel HD, Kannangai R, Offerhaus GJ, Velculescu VE, Wang L, Zhou S, Vogelstein B, Hruban RH, Papadopoulos N, Cai J, Torbenson MS, Kinzler KW (September 2011). "Inactivating mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID2 in hepatocellular carcinoma". Nat. Genet. 43 (9): 828–9. PMC 3163746

. PMID 21822264. doi:10.1038/ng.903.

. PMID 21822264. doi:10.1038/ng.903. - ↑ Shain AH, Giacomini CP, Matsukuma K, Karikari CA, Bashyam MD, Hidalgo M, Maitra A, Pollack JR (January 2012). "Convergent structural alterations define SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeler as a central tumor suppressive complex in pancreatic cancer". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (5): E252–9. PMC 3277150

. PMID 22233809. doi:10.1073/pnas.1114817109.

. PMID 22233809. doi:10.1073/pnas.1114817109. - ↑ Varela I, Tarpey P, Raine K, Huang D, Ong CK, Stephens P, Davies H, Jones D, Lin ML, Teague J, Bignell G, Butler A, Cho J, Dalgliesh GL, Galappaththige D, Greenman C, Hardy C, Jia M, Latimer C, Lau KW, Marshall J, McLaren S, Menzies A, Mudie L, Stebbings L, Largaespada DA, Wessels LF, Richard S, Kahnoski RJ, Anema J, Tuveson DA, Perez-Mancera PA, Mustonen V, Fischer A, Adams DJ, Rust A, Chan-on W, Subimerb C, Dykema K, Furge K, Campbell PJ, Teh BT, Stratton MR, Futreal PA (January 2011). "Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma". Nature. 469 (7331): 539–42. PMC 3030920

. PMID 21248752. doi:10.1038/nature09639.

. PMID 21248752. doi:10.1038/nature09639. - ↑ Shain AH, Pollack JR (2013). "The spectrum of SWI/SNF mutations, ubiquitous in human cancers". PLoS ONE. 8 (1): e55119. PMC 3552954

. PMID 23355908. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055119.

. PMID 23355908. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055119. - ↑ Bennett-Lovsey R, Hart SE, Shirai H, Mizuguchi K (2002). "The SWIB and the MDM2 domains are homologous and share a common fold.". Bioinformatics. 18 (4): 626–30. PMID 12016060. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/18.4.626.

- 1 2 3 Decristofaro MF, Betz BL, Rorie CJ, Reisman DN, Wang W, Weissman BE (2001). "Characterization of SWI/SNF protein expression in human breast cancer cell lines and other malignancies.". J Cell Physiol. 186 (1): 136–45. PMID 11147808. doi:10.1002/1097-4652(200101)186:1<136::AID-JCP1010>3.0.CO;2-4.

- ↑ Collingwood TN, Urnov FD, Wolffe AP (1999). "Nuclear receptors: coactivators, corepressors and chromatin remodeling in the control of transcription". J. Mol. Endocrinol. 23 (3): 255–75. PMID 10601972. doi:10.1677/jme.0.0230255.