Superior vena cava syndrome

| Superior vena cava syndrome (Mediastinal syndrome) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Superior vena cava syndrome in a person with bronchogenic carcinoma. Note the swelling of his face first thing in the morning (left) and its resolution after being upright all day (right). | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | cardiology |

| ICD-10 | I87.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 459.2 |

| DiseasesDB | 12711 |

| MedlinePlus | 001097 |

| eMedicine | emerg/561 |

| MeSH | D013479 |

Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), is a group of symptoms caused by obstruction of the superior vena cava (a short, wide vessel carrying circulating blood into the heart). More than 90% of cases of superior vena cava obstruction (SVCO) are caused by cancer - most commonly bronchogenic carcinoma, typically a tumor outside the vessel compressing the vessel wall. It can also be caused by compression from an aortic aneurism or it can sometimes have a benign cause. Characteristic features are edema (swelling due to excess fluid) of the face and arms and development of swollen collateral veins on the front of the chest wall. Shortness of breath and coughing are quite common symptoms; difficulty swallowing is reported in 11% of cases, headache in 6% and stridor (a high-pitched wheeze) in 4%. The condition is rarely life-threatening, though edema of the epiglottis can make breathing difficult, and edema of the brain can cause reduced alertness, and in less than 5% of cases of SVCO, severe neurological symptoms or airway compromise are reported.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Shortness of breath is the most common symptom, followed by face or arm swelling.[2]

Following are frequent symptoms:

- Difficulty breathing[3]

- Headache[3]

- Facial swelling[3]

- Venous distention in the neck and distended veins in the upper chest and arms[3]

- Upper limb edema[3]

- Lightheadedness[2]

- Cough[2]

- Edema (swelling) of the neck, called the collar of Stokes[4]

- Pemberton's sign[3]

Superior vena cava syndrome usually presents more gradually with an increase in symptoms over time as malignancies increase in size or invasiveness.[2]

Cause

Approximately 90% of cases are associated with a cancerous tumor that is compressing the superior vena cava,[2] such as bronchogenic carcinoma including small cell and non-small cell lung carcinoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, lymphoblastic lymphomas, pre-T-cell lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (rare), and other acute leukemias.[2] Syphilis and tuberculosis have also been known to cause superior vena cava syndrome.[2] SVCS can be caused by invasion or compression by a pathological process or by thrombosis in the vein itself, although this latter is less common (approximately 35% due to the use of intravascular devices).[2]

Diagnosis

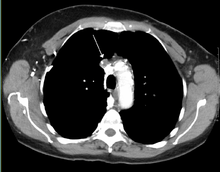

The main techniques of diagnosing SVCS are with chest X-rays (CXR), CT scans, transbronchial needle aspiration at bronchoscopy and mediastinoscopy.[3] CXRs provide the ability to show mediastinal widening and may show the presenting primary cause of SVCS.[3] CT scans should be contrast enhanced and be taken on the neck, chest, lower abdomen and pelvis.[3] They may also show the underlying cause and the extent to which the disease has progressed.[3]

Treatment

Several methods of treatment are available, mainly consisting of careful drug therapy and surgery.[2] Glucocorticoids (such as prednisone or methylprednisolone) decrease the inflammatory response to tumor invasion and edema surrounding the tumor.[2] Glucocorticoids are most helpful if the tumor is steroid-responsive, such as lymphomas. In addition, diuretics (such as furosemide) are used to reduce venous return to the heart which relieves the increased pressure.[2]

In an acute setting, endovascular stenting by an interventional radiologist may provide relief of symptoms in as little as 12–24 hours with minimal risks.

Should a patient require assistance with respiration whether it be by bag/valve/mask, BiPAP, CPAP or mechanical ventilation, extreme care should be taken. Increased airway pressure will tend to further compress an already compromised SVC and reduce venous return and in turn cardiac output and cerebral and coronary blood flow. Spontaneous respiration should be allowed during endotracheal intubation until sedation allows placement of an ET tube and reduced airway pressures should be employed when possible.

Prognosis

Symptoms are usually relieved with radiation therapy within one month of treatment.[2] However, even with treatment, 99% of patients die within two and a half years.[2] This relates to the cancerous causes of SVC that are 90% of the cases. The average age of onset of disease is 54 years of age.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ Kent, MS; Port, JL (2007). "Superior Vena Cava Syndrome". In Chang, AE; Ganz, PA; Hayes, DF; et al. Oncology – An Evidence-based Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1291–9. ISBN 0387310568.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 emedicine > Superior Vena Cava Syndrome. Author: Michael S Beeson, MD, MBA, FACEP, Professor of Emergency Medicine, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine and Pharmacy; Attending Faculty, Summa Health System. Updated: Dec 3, 2009

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Parker, Robert; Catherine Thomas; Lesley Bennett (2007). Emergencies in Respiratory Medicine. Oxford. pp. 96–7. ISBN 978-0-19-920244-7.

- ↑ define:collar of Stokes at open-resource-project.org. Retrieved Mars 2011

External links

- Superior vena cava syndrome at eMedicine

- Wilson LD, Detterbeck FC, Yahalom J (May 2007). "Clinical practice. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes". N Engl J Med. 356 (18): 1862–9. PMID 17476012. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp067190.

- Randolph HL Wong; Joshua Chai; Calvin SH Ng; et al. (2009). "Transvenous pacing lead-induced Superior Vena Cava Syndrome: What do we know?". Surgical Practice. 13 (4): 125–126. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1633.2009.00462.x.