STS-41-C

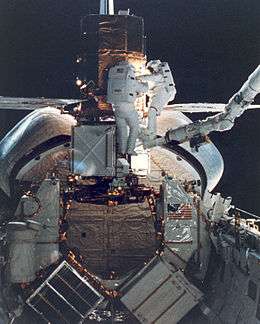

Mission Specialists George Nelson and James van Hoften repair the captured Solar Maximum Mission Satellite on 11 April 1984. | |

| Mission type |

Satellite deployment Satellite repair |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1984-034A |

| SATCAT no. | 14897 |

| Mission duration | 6 days, 23 hours, 40 minutes, 7 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 4,620,000 kilometres (2,870,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 108 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Challenger |

| Launch mass | 115,328 kilograms (254,254 lb) |

| Landing mass | 89,346 kilograms (196,975 lb) |

| Payload mass | 15,345 kilograms (33,831 lb)[1] |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 5 |

| Members |

Robert L. Crippen Francis R. Scobee Terry J. Hart James D. A. van Hoften George D. Nelson |

| EVAs | 2 |

| EVA duration |

10 hours, 6 minutes First: 2 hours, 59 minutes Second: 7 hours, 7 minutes |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | April 6, 1984, 13:58:00 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | April 13, 1984, 13:38:07 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 17 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee | 222 kilometres (138 mi) |

| Apogee | 468 kilometres (291 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.5 degrees |

| Period | 91.4 min |

| Epoch | April 8, 1984[2] |

Left to right: Crippen, Hart, van Hoften, Nelson, Scobee | |

STS-41-C was NASA's 11th Space Shuttle mission, and the fifth mission of Space Shuttle Challenger. The launch, which took place on April 6, 1984, marked the first direct ascent trajectory for a shuttle mission. During the mission, Challenger's crew captured and repaired the malfunctioning Solar Maximum Mission ("Solar Max") satellite, and deployed the Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) experimental apparatus. STS-41-C was extended one day due to problems capturing the Solar Max satellite, and the landing on April 13 took place at Edwards Air Force Base, instead of at Kennedy Space Center as had been planned. The flight was originally numbered STS-13.[3][4]

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Robert L. Crippen Third spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Francis R. Scobee First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Terry J. Hart Only spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | James D. A. van Hoften First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | George D. Nelson First spaceflight | |

Spacewalks

- EVA 1

- Personnel: Nelson and van Hoften

- Date: April 8, 1984 (14:18–16:56 UTC)

- Duration: 2 hours, 59 minutes[5]

- EVA 2

- Personnel: Nelson and van Hoften

- Date: April 11, 1984 (08:58–15:42 UTC)

- Duration: 7 hours, 7 minutes[5]

Crew seating arrangements

| Seat[6] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Crippen | Crippen | |

| S2 | Scobee | Scobee | |

| S3 | Hart | Nelson | |

| S4 | van Hoften | van Hoften | |

| S5 | Nelson | Hart | |

Mission summary

STS-41-C launched successfully at 8:58 am EST on April 6, 1984. The mission marked the first direct ascent trajectory for the Space Shuttle; Challenger reached its 288-nautical-mile-(533-km)-high orbit using its Orbiter Maneuvering System (OMS) engines only once, to circularize its orbit. During the ascent phase, the main computer in Mission Control failed, as did the backup computer. For about an hour, the controllers had no data on the orbiter.[7]

The flight had two primary objectives. The first was to deploy the Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF), a passive, retrievable, 12-sided experimental cylinder. The 21,300-pound (9,700 kg) LDEF was 14 feet (4.3 m) in diameter and 30 feet (9.1 m) long, and carried 57 scientific experiments. The second objective of STS-41-C was to capture, repair and redeploy the malfunctioning Solar Maximum Mission satellite ("Solar Max"), which had been launched in 1980.

On the second day of the flight, the LDEF was grappled by the "Canadarm" Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm and successfully released into orbit. Its 57 experiments, mounted in 86 removable trays, were contributed by 200 researchers from eight countries. Retrieval of the passive LDEF was initially scheduled for 1985, but schedule delays and the Challenger disaster of 1986 postponed the retrieval until January 12, 1990, when Columbia retrieved the LDEF during STS-32.

On the third day of the mission, Challenger's orbit was raised to about 300 nautical miles (560 km), and it maneuvered to within 200 feet (61 m) of the stricken Solar Max satellite. Astronauts Nelson and van Hoften, wearing spacesuits, entered the payload bay. Nelson, using the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), flew out to the satellite and attempted to grasp it with a special capture tool, called the Trunnion Pin Acquisition Device (TPAD). Three attempts to clamp the TPAD onto the satellite failed. Solar Max began tumbling on multiple axes when Nelson attempted to grab one of the satellite's solar arrays by hand, and the effort was called off. Crippen had to perform multiple maneuvers of the orbiter to keep up with Nelson and Solar Max, and nearly ran out of RCS fuel.[7]

During the night of the third day, the Solar Max POCC, located at Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, was able to establish control over the satellite by sending commands ordering the satellite's magnetorquers to stabilize its tumbling. This was successful, and Solar Max went into a slow, regular spin. The next day, Crippen maneuvered Challenger back to Solar Max, and Hart was able to grapple the satellite with the RMS. They placed Solar Max on a special cradle in the payload bay using the RMS. Nelson and van Hoften then began the repair operation, replacing the satellite's attitude control mechanism and the main electronics system of the coronagraph instrument. The ultimately successful repair effort took two separate spacewalks. Solar Max was deployed back into orbit the next day. After a 30-day checkout by the Goddard POCC, the satellite resumed full operation.

Other STS-41-C mission activities included a student experiment located in a middeck locker which found that honeybees can successfully make honeycomb cells in a microgravity environment. Highlights of the mission, including the LDEF deployment and the Solar Max repair, were filmed using an IMAX movie camera, and the results appeared in the 1985 IMAX movie The Dream is Alive.

The 6-day, 23-hour, 40-minute, 7-second mission ended on April 13, 1984, at 5:38 am PST, when Challenger landed safely on Runway 17, at Edwards AFB, having completed 108 orbits. Challenger was returned to KSC on April 18, 1984.

The launch of STS-41-C on April 6, 1984.

The launch of STS-41-C on April 6, 1984. The deployed Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF), which became an important source of information on the small-particle space debris environment.

The deployed Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF), which became an important source of information on the small-particle space debris environment. George Nelson attempts to capture the Solar Maximum Mission satellite.

George Nelson attempts to capture the Solar Maximum Mission satellite. STS-41-C touches down at Runway 17, Edwards Air Force Base, on April 13, 1984.

STS-41-C touches down at Runway 17, Edwards Air Force Base, on April 13, 1984.

Wake-up calls

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, and first used music to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[9]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist/Composer |

|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | "A Boy Named Sue" | Johnny Cash |

| Day 3 | "Fight for California" | |

| Day 4 | Unidentified | |

| Day 5 | "Theme from Rocky" | Bill Conti |

| Day 6 | Unidentified | |

| Day 7 | None | |

| Day 8 | "University of Texas Fight Song" |

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ↑ "NASA shuttle cargo weight summary" (PDF). Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ↑ McDowell, Jonathan. "SATCAT". Jonathan's Space Pages. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ↑ "James D. A. van Hoften" (PDF). NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. December 5, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Terry J. Hart" (PDF). NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. April 10, 2003. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- 1 2 "STS-41-C". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ↑ "STS-41C". Spacefacts. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- 1 2 Hale, Wayne (May 28, 2012). "Ground Up Rendezvous". Wayne Hale's Blog. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ Ben Evans (2007). Space Shuttle Challenger: Ten Journeys into the Unknown. Google Books. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ↑ Fries, Colin (June 25, 2007). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

External links

- STS-41-C mission summary. NASA.

- STS-41-C video highlights. NSS

- The Dream is Alive (1985). IMDb.

- STS-41-C NST Program Mission Report (PDF). NASA.