STS-114

_approaches_the_International_Space_Station.jpg) Discovery photographed from the International Space Station as it performs the first ever rendezvous pitch maneuver. | |

| Mission type | ISS logistics |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 2005-026A |

| SATCAT no. | 28775 |

| Mission duration | 13 days, 21 hours, 32 minutes, 48 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 9,300,000 kilometres (5,800,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 219 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Discovery |

| Launch mass | 121,483 kilograms (267,824 lb) |

| Landing mass | 102,913 kilograms (226,884 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 7 |

| Members |

Eileen Collins James M. Kelly Soichi Noguchi Stephen K. Robinson Andrew S. W. Thomas Wendy B. Lawrence Charles J. Camarda |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 26 July 2005, 14:39:00 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 9 August 2005, 12:11:22 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 22 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee | 350 kilometres (220 mi)[1] |

| Apogee | 355 kilometres (221 mi)[1] |

| Inclination | 51.6 degrees[1] |

| Period | 91.59 minutes[1] |

| Epoch | 31 July 2005[1] |

| Docking with ISS | |

| Docking port |

PMA-2 (Destiny forward) |

| Docking date | 28 July 2005, 11:18 UTC |

| Undocking date | 6 August 2005, 07:24 UTC |

| Time docked | 8 days, 19 hours, 54 minutes |

Back (L-R): Robinson, Thomas, Camarda, Noguchi Front (L–R): Kelly, Lawrence, Collins | |

STS-114 was the first "Return to Flight" Space Shuttle mission following the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster. Discovery launched at 10:39 EDT (14:39 UTC), 26 July 2005. The launch, 907 days (approx. 29 months) after the loss of Columbia, was approved despite unresolved fuel sensor anomalies in the external tank that had prevented the shuttle from launching on 13 July, its originally scheduled date.

The mission ended on 9 August 2005 when Discovery landed at Edwards Air Force Base in California.[2] Poor weather over the Kennedy Space Center in Florida hampered the shuttle from using its primary landing site.

Analysis of the launch footage showed debris separating from the external tank during ascent; it was the issue that had set off the Columbia disaster. As a result, NASA decided on 27 July to postpone future shuttle flights pending additional modifications to the flight hardware. Shuttle flights resumed a year later with STS-121 on 4 July 2006.

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Fourth and final spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Third spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Fourth and final spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 4 | Fourth and final spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 5 | First spaceflight | |

Original crew

This mission was to carry the Expedition 7 crew to the ISS and bring home the Expedition 6 crew. The original crew was to be:

| Position | Launching Astronaut | Landing Astronaut |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | ||

| Pilot | ||

| Mission Specialist 1 | ||

| Mission Specialist 2 | ||

| Mission Specialist 3 | Expedition 7 ISS Commander |

Expedition 6 ISS Commander |

| Mission Specialist 4 | Expedition 7 ISS Flight Engineer |

Expedition 6 ISS Flight Engineer |

| Mission Specialist 5 | Expedition 7 ISS Flight Engineer |

Expedition 6 ISS Flight Engineer |

Mission highlights

STS-114 marked the return to flight of the Space Shuttle after the Columbia disaster and was the second Shuttle flight with a female commander (Eileen Collins, who also commanded the STS-93 mission). The STS-114 mission was initially to be flown aboard the orbiter Atlantis, but NASA replaced it with Discovery after improperly installed gear was found in Atlantis' Rudder Speed Brake system. During OMM for Discovery, an actuator on the RSB system was found to be installed incorrectly. This created a fleet wide suspect condition. The Rudder Speed Brake system was removed and refurbished on all three remaining orbiter vehicles, and since Discovery's RSB was corrected first, it became the new Return to Flight vehicle, superseding Atlantis. Seventeen years prior, Discovery had flown NASA's previous Return to Flight mission, STS-26.

The STS-114 mission delivered supplies to the International Space Station. However, the major focus of the mission was testing and evaluating new Space Shuttle flight safety techniques, which included new inspection and repair techniques. The crewmembers used the new Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) – a set of instruments on a 50-foot (15 m) extension attached to the Canadarm. The OBSS instrument package consists of visual imaging equipment and a Laser Dynamic Range Imager (LDRI) to detect problems with the shuttle's Thermal Protection System (TPS). The crew scanned the leading edges of the wings, the nose cap, and the crew compartment for damage, as well as other potential problem areas engineers wished to inspect based on video taken during lift-off.

STS-114 was classified as Logistics Flight 1. The flight carried the Raffaello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module, built by the Italian Space Agency, as well as the External Stowage Platform-2, which was mounted to the port side of the Quest Airlock. They deployed MISSE 5 to the station's exterior, and replaced one of the ISS's Control Moment Gyroscopes (CMG). The CMG was carried up on the LMC (Lightweight Multi-Purpose Experiment Support Structure Carrier) at the rear of the payload bay, together with the TPS Repair Box.

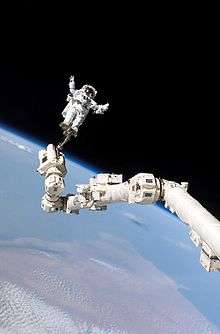

The crew conducted three spacewalks while at the station. The first demonstrated repair techniques on the Shuttle's Thermal Protection System. During the second, the spacewalkers replaced the failed gyroscope. On the third, they installed the External Stowage Platform and repaired the shuttle, the first time repairs had been carried out during a spacewalk on the exterior of a spacecraft in flight. On 1 August, it was announced that protruding gap fillers on the front underside of the shuttle would be inspected and dealt with during the third spacewalk of the mission. The spacewalk was conducted on the morning of 3 August. Robinson easily removed the two fillers with his fingers. Later on the same day, NASA officials said that they were looking closely at a thermal blanket located next to the commander's window on the port side of the orbiter. Published reports on 4 August 2005 said that wind tunnel testing had demonstrated that the orbiter was safe to re-enter with the billowed blanket.

On 30 July 2005, NASA announced that STS-114 would be extended for one day, so that Discovery's crew could help the ISS crew maintain the station while the shuttle fleet was grounded. The extra day was also used to move more items from the shuttle to the ISS, as uncertainty mounted during the mission as to when a shuttle would next visit the station. The orbiter's arrival also gave the nearly 200-ton space station a free altitude boost of about 4,000 feet (1,220 m). The station loses about 100 feet (30 m) of altitude a day.[3]

The shuttle hatch was closed the night before it undocked from the ISS. After undocking, the shuttle flew around the station to take photos.

Atmospheric reentry and landing was originally planned for 8 August 2005, at Kennedy Space Center, but unsuitable weather postponed the landing until the next day, then moved it to Edwards Air Force Base in California, where Discovery touched down at 08:11EDT (05:11 am PDT, 12:11 UTC).

Launch sequence anomalies

Around 2.5 seconds after lift-off, a large bird struck near the top of the external fuel tank, and appeared in subsequent video frames to slide down the tank. NASA did not expect this to hurt the mission because it did not hit the orbiter, and because the vehicle was traveling relatively slowly at the time.

A small fragment of thermal tile, estimated to be around 1.5 inches (38 mm) in size, was ejected from an edge tile of the front landing gear door at some point before SRB separation. A small white area appeared on the tile as the piece detached, and the loose shard could be seen in a single frame of the video. It is unknown what object (if any) struck the tile to cause the damage. The damaged tile was inspected further when the images from the umbilical camera were downloaded on day three. Engineers requested that this area be inspected by the OBSS, and flight managers scheduled the operation for 29 July 2005. This represented the only known possible damage to Discovery that could have posed a risk during re-entry.

At 127.1 seconds after liftoff, and 5.3 seconds after SRB separation, a large piece of debris separated from the Protuberance Air Load (PAL) ramp, which is part of the external tank. The debris was thought to have measured 36.3 by 11 by 6.7 inches (922 by 279 by 170 mm) – and to weigh about 0.45 kilograms (0.99 lb), or half as much as the piece of foam blamed for the loss of Columbia.[4] The debris piece did not strike any part of the Discovery orbiter. Images of the external tank taken after separation from the orbiter show multiple areas where foam insulation was missing.

Around 20 seconds later, a smaller piece of foam separated from the ET and apparently struck the orbiter's right wing. Based on the mass of the foam, and the velocity at which it would have struck the wing, NASA estimated it only exerted one-tenth the energy required to cause potential damage. Laser scanning and imaging of the wing by the OBSS did not reveal any damage. On 27 July 2005, NASA announced that it was postponing all Shuttle flights until the foam loss problem could be resolved.

As with Columbia, NASA at first believed that workers' improper installation and handling of the external tanks at the Michoud Assembly Facility in Louisiana caused the foam loss on Discovery.[5] NASA Administrator Michael Griffin stated that the earliest the next shuttle could launch is 22 September 2005, but that's only "if next week, the guys have a Aha! effect on the foam and spot why this big chunk came off." Later in August, it became clear that a September launch date would not be possible, and that the earliest date for the next launch would be in March 2006. However, because Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast, the next launch was delayed further. With the destruction suffered by Michoud and NASA's Stennis Space Center in Mississippi due to Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent flooding, the launch of the next shuttle mission (STS-121) was further delayed until 4 July 2006.

In December 2005 x-ray photographs of another tank showed that thermal expansion and contraction during filling, not human error, caused the cracks that resulted in foam loss. NASA official Wayne Hale formally apologized to the Michoud workers who had been blamed for the loss of Columbia for almost three years.[6]

In-flight repair

On the third EVA of the mission, two areas on the underside of the shuttle where photographic surveying identified protruding gap fillers were dealt with. According to NASA, the gap fillers, which each serve different purposes, are not required for reentry. One filler prevents "chattering" of tiles during ascent, which would occur due to the sonic booms from the noses of the solid rocket boosters and the external fuel tank. The other, in a different location where there is a wider gap between tiles, simply functions to reduce the gap size between tiles, which in turn reduces heat transfer to the shuttle. Even without this filler NASA did not expect the increased heat to cause a problem during reentry (it is present to avoid a level of heating which would only be problematic if experienced many times over a vehicle's design life). Since the gap fillers are not necessary for re-entry, it was acceptable to simply pull them out. An overview of the situation, including procedures for dealing with the protrusions, were sent electronically to the crew and printed aboard the shuttle. The crew were also able to watch uploaded videos of NASA personnel on the ground demonstrating the repair techniques. Both the videos and 12-page procedure document[7] were also made publicly available via NASA's website.

During the third EVA, both the fillers were successfully removed with less than a pound of force without the need to use any tools. Stephen K. Robinson gave a running commentary of his work: "I'm grasping it and I'm pulling it and it's coming out very easily" ... "It looks like this big patient is cured".

If it was not possible to pull the fillers out, then the protruding sections could have been simply cut off. The gap fillers were made of a cloth impregnated with ceramic – they were stiff and could be easily cut with a tool similar to a hacksaw blade. Protruding gap fillers were a problem because they disrupted the normally laminar air flow under the orbiter during reentry, causing turbulence at lower speeds. A turbulent air flow would result in a mixing of hot and cold air, which could have a major effect on the shuttle temperature.

The decision to make the repair balanced the risks of the EVA with the risks of leaving the protruding gap fillers as they were. It is thought that gap filler protrusions of a similar magnitude were present on previous missions, but were not observed in-orbit. Consideration was also given to the risks of elements of the procedure which would involve the ISS arm being used to carry Stephen K. Robinson below the shuttle, possibly the use of a sharp tool which had the potential to damage the EVA suit or shuttle tiles. The possibility of making things worse by attempting a repair was given serious consideration. Cameras on the shuttle arm and on Robinson's helmet were used to monitor the activities under the shuttle.

Protruding gap fillers had been identified as an issue on previous flights, notably STS-28. A post-flight analysis[8] identified that a gap filler was the likely cause of the high temperatures observed during this re-entry. Protruding gap fillers were also seen on STS-73.

A further in-flight repair was considered to remove or clip a damaged thermal blanket located beneath the commander's window on the port side of the orbiter. Wind tunnel testing by NASA determined that the thermal blanket was safe for re-entry, and plans for a fourth spacewalk were cancelled.

Mission timeline

This timeline is a summary. For a more detailed timeline, see NASA Timeline of Significant Mission Events.

13 July

- 11:55 EDT – The countdown clock was restarted after a programmed 3 hour hold.

- 12:01 EDT – To loud applause and cheers, the crew entered the traditional Astrovan to make their way to the pad.

- 12:30 EDT – The crew arrived at Pad 39B and proceeded into the White Room for boarding.

- 13:32 EDT – Problem with LH2 fuel level sensor reported. Launch Director orders launch scrubbed.

- 13:34 EDT – Crew egress began.

- 13:59 EDT – Crew egress completed.

14 July

- 14:00 EDT – Technical meeting of Mission Management Team to discuss troubleshooting efforts following the draining of the External Tank (ET) the previous night.

- 14:45 EDT – Press conference, earliest possible liftoff moved to Sunday, 17 July. During this press conference it was confirmed that the preparations of Atlantis for the next scheduled flight (STS-121) were not being delayed while troubleshooting the sensor problem on Discovery. This could have impacted the contingency planning for the mission.

26 July

- 08:08 EDT: Crew boarding complete.

- 09:00 EDT: Shuttle hatch closed.

- 09:24 EDT: T −20 minutes and holding.

- 09:34 EDT: T −20 minutes and counting.

- 09:45 EDT: T-9 minutes and holding.

- 10:27 EDT: Launch Control reports go for launch

- 10:30 EDT: T −9 minutes and counting.

- 10:35 EDT: T −4 minutes, APU activation complete.

- 10:39 EDT: Liftoff, shuttle has cleared the tower

- 10:47 EDT: T +8 minutes, main engine shutdown and fuel tank separation as planned.

28 July

- 07:18 EDT: T +01:20:39 Orbiter docked with ISS after performing the first-ever Rendezvous pitch maneuver

30 July

- 05:46 EDT: T +03:19:07 Noguchi and Robinson begin first spacewalk

- 12:36 EDT: T +04:02:57 Spacewalk completed successfully (duration 6 h 50 min)

1 August

- 04:44 EDT: T +05:18:05 Noguchi and Robinson begin second spacewalk to replace CMG

- 11:14 EDT: T +06:00:35 Spacewalk completed successfully (duration 6 h 30 min)

3 August

- 04:48 EDT: T +07:18:09 Noguchi and Robinson begin third spacewalk. Robinson to remove two protruding gap fillers between thermal insulation tiles. Noguchi installs amateur radio satellite PCSat2 along with the MISSE 5 experiment to test solar cells.

- 10:49 EDT: T +08:00:10 Spacewalk completed successfully (duration 6 h 1 min)

6 August

- 01:14 EDT: T+10:14:35 Orbiter crew bids farewell to ISS crew. Hatches between orbiter and ISS closed

- 03:24 EDT: T+10:16:45 Orbiter undocks from ISS

8 August

- 03:20 EDT: T+12:16:41 Mission Control waves off the first of two landing opportunities for Space Shuttle Discovery due to low clouds over Kennedy Space Center

- 05:04 EDT: T+12:18:25 Mission Control waves off the second landing attempt, delaying the landing for another day. Landing is now tentatively scheduled for 05:07 EDT 9 August at Kennedy Space Center. In the event of inclement weather in Florida, NASA will land Discovery at Edwards Air Force Base in California, or, as a last resort, White Sands, New Mexico.

9 August

- 03:12 EDT: T+13:16:33 Mission Control waves off the first landing opportunity for Discovery due to bad weather.

- 05:03 EDT: T+13:18:24 Mission Control waves off the second landing opportunity due to thunderstorms within the 30-nautical-mile (56 km) "safety zone" around KSC. Shuttle Discovery will now land at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The previous landing at Edwards Air Force Base was STS-111 on 19 June 2002. The last previous night landing at Edwards was STS-48 on 18 September 1991.

- 06:43 EDT: T+13:20:04 Capcom (Ken Ham), tells Discovery that "it's time to come home".

- 07:06 EDT: T+13:20:27 Discovery begins its 2-minute, 42-second retrograde deorbit burn over the Western Indian Ocean to the north of Madagascar.

- 07:09 EDT: T+13:20:30 Deorbit burn completed as planned, slowing the shuttle by 186 mi/h (300 kilometres (190 mi)/h).

- 07:28 EDT: T+13:20:49 APUs are activated to power the shuttle's control surfaces

- 07:40 EDT: T+13:21:01 Discovery begins to feel the effects of the Earth's atmosphere.

- 08:08 EDT: T+13:21:29 Commander Eileen Collins takes control of Discovery for final approach to Runway 22.

- 08:11 EDT: T+13:21:32 Discovery touches down at Edwards Air Force Base. NASA commentator: "and Discovery is home."

- 08:12 EDT: T+13:21:33 Eileen Collins reports "Wheel stop."

- 10:13 EDT: Crew leaves shuttle.

Wake-up calls

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, which was first used to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by their families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[9]

- Day 2: "I Got You Babe", Sonny & Cher, From the movie "Groundhog Day", played for the entire crew. WAV MP3

- Day 3: "What A Wonderful World", Louis Armstrong, played for Charles Camarda. WAV MP3

- Day 4: "Vertigo", U2, played for Jim Kelly. WAV MP3

- Day 5: "Sanpo" ("Stroll"), from the movie "My Neighbor Totoro", composed by Joe Hisaishi and performed by the Japanese School of Houston, played for Soichi Noguchi. WAV MP3

- Day 6: "I'm Goin' Up", Claire Lynch, played for Wendy Lawrence. WAV MP3

- Day 7: "Walk of Life", Dire Straits, played for Steve Robinson. WAV MP3

- Day 8: "Big Rock Candy Mountain", Harry McClintock, played for Andy Thomas. WAV MP3

- Day 9: "Faith of the Heart", Title song of Star Trek: Enterprise, Diane Warren performed by Russell Watson, played for Commander Eileen Collins. WAV MP3

- Day 10: "Amarillo by Morning", George Strait, played for the entire crew. WAV MP3

- Day 11: "Anchors Aweigh", The United States Navy, played for Wendy Lawrence. WAV MP3

- Day 12: "The Air Force Song", played for Jim Kelly in congratulations on his promotion to Air Force Colonel. WAV MP3

- Day 13: "The One and Only Flower in the World", SMAP, played for Soichi Noguchi. WAV MP3

- Day 14: "Come On Eileen", Dexys Midnight Runners, played for Eileen Collins. WAV MP3

- Day 15: "Good Day Sunshine", The Beatles, played for the entire crew. WAV MP3

Crew salute to Husband family

On flight day 10, the entire STS-114 crew, and the crew of Expedition 11 gathered to wish Rick Husband's son Matthew, a happy birthday. Rick Husband was the commander of Columbia on STS-107.

| “ | We know it's still August third down there on the planet Earth, and from the Shuttle Discovery we would like to say "Happy birthday" to Matthew Husband, who is ten years old today. And Houston, that wake-up music sure makes me think of Rick Husband's mom, who lives in Amarillo, so we'd like to say "Hi" to Mrs. Husband, too. -Commander Eileen Collins and Pilot Jim Kelly | ” |

Mission hardware

- SSME 1: 2057

- SSME 2: 2054

- SSME 3: 2056

- External Tank: ET-121

- SRB Set: BI-125

- RSRM Set: 92

Contingency planning

Since the loss of Columbia in STS-107, it had been suggested that on future shuttle missions there would be a planned rescue capability involving having a second shuttle ready to fly at short notice. Even prior to the sensor problem causing the delay in the launch, a rescue option (called STS-300 by NASA) had been planned, which involved the crew of STS-114 remaining docked at the International Space Station until Atlantis could be launched with a four-person crew to retrieve the astronauts. Discovery would then be ditched by remote control over the Pacific Ocean, with Atlantis bringing back both its own crew, as well as that of Discovery.

A further option for rescue would be to use Russian Soyuz spacecraft. Nikolay Sevastyanov, director of the Russian Space Corporation Energia, was reported by Pravda as saying: "If necessary, we will be able to bring home nine astronauts on board three Soyuz spacecraft in January and February of the next year".[10]

See also

- 2005 in spaceflight

- List of human spaceflights

- List of human spaceflights to the ISS

- List of Space Shuttle missions

- Outline of space science

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 McDowell, Jonathan. "Satellite Catalog". Jonathan's Space Page. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ Fabara, Jet. 2005. Shuttle Discovery lands at Edwards after successful space mission. Desert Wing, Vol. 57, No. 32, 12 August 2005 issue, pp. 1, 3.

- ↑ "Return to Flight". NASA.

- ↑ "STS-114 External Tank Tiger Team Report" (PDF). NASA. 7 October 2005.

- ↑ Watson, Traci (4 August 2005). "Workers at fault for foam?". USA Today. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Hale, Wayne (2012-04-18). "How We Nearly Lost Discovery". waynehale.wordpress.com. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "Gap filler removal task summary notes" (PDF). NASA.

- ↑ Smith, J.A. (December 1989). "STS-28R Early Boundary Layer Transition" (PDF). NASA.

- ↑ Fries, Colin (25 June 2007). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

- ↑ Discovery shuttle destroys USA's image of technological predominance – Pravda.Ru

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to STS-114. |

- NASA's official Return to Flight site

- Spaceflightnow Launch weblog

- projected landing track

- NASA-TV Home Page

- ET redesign and photos of PAL ramps.

- NASA Shuttle Discovery 2005 – Robinson Space Panorama

- STS-114 Video Highlights

- Video – Aerial view of space shuttle Discovery launch from WB-57 aircraft YouTube

- Video of the launch of Discovery from the KSC Press Site YouTube