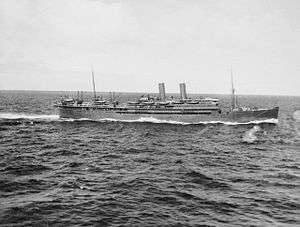

SS Slamat

SS Slamat during World War II | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | SS Slamat |

| Owner: | Koninklijke Rotterdamsche Lloyd |

| Operator: | W Ruys & Zonen (until 1940) |

| Port of registry: | |

| Builder: | Koninklijke Maatschappij De Schelde, Vlissingen |

| Yard number: | 176[1] |

| Completed: | 1924 |

| Identification: |

|

| Fate: | sunk by Ju 87 dive-bomber aircraft |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 62.0 ft (18.9 m) |

| Depth: |

|

| Decks: | 3 |

| Propulsion: | steam turbines; twin screw |

| Speed: | |

| Crew: |

|

| Sensors and processing systems: | submarine signalling apparatus; wireless direction finding |

| Armament: | DEMS |

| Notes: | Peacetime livery: dove-grey hull, white superstructure, black funnels |

SS Slamat (or "DSS Slamat", with DSS standing for dubbelschroefstoomschip, "twin-screw steamship") was a Dutch ocean liner of the Rotterdam-based Koninklijke Rotterdamsche Lloyd line. Although she was a turbine steamship, she tended not to be referred to as "TSS". She was built in Vlissingen in the Netherlands in 1924 for liner service between Rotterdam and the Dutch East Indies. In 1940 she was converted into a troop ship. In 1941 she was sunk with great loss of life in the Battle of Greece.

Building and peacetime service

Koninklijke Maatschappij De Schelde built Slamat in Vlissingen on the River Scheldt, completing her in 1924. Her boilers had oil-burning furnaces, and her engines were steam turbines that drove her twin screws via double reduction gearing. She was equipped with submarine signalling apparatus, which in the 1920s was seen as an alternative to radio. She also had wireless direction finding equipment.[5]

Slamat was built for Koninklijke Rotterdamsche Lloyd (KRL or "Royal Dutch Lloyd") and managed by Willem Ruys en Zonen.[5] Willem Ruys ran KRL and the two companies were part of the same group. KRL ships operated passenger and cargo services between Rotterdam and the Dutch East Indies via Southampton, Marseille and the Suez Canal.[3][6] Slamat was KRL's last major steam turbine passenger liner before it started introducing motor ships: Indrapoera in 1925, Sibajak in 1927 and the larger and swifter Baloeran and Dempo in 1929.[3]

In 1931 Slamat was refitted and lengthened[4] by 27.6 feet (8.4 m), which slightly increased each of her tonnages.[7] Her speed was increased to 17 knots (31 km/h).[4]

In peacetime Slamat carried KRL's livery of dove-grey hull, white superstructure and black funnels.[8]

War service

When the Second World War began the Netherlands was neutral. In mid-October 1939 Slamat left Rotterdam for the East Indies, calling at Lisbon, Cape Verde, Cape Town, Mauritius, Sabang and Singapore before reaching Batavia, capital of the Dutch East Indies, on 30 November. On 1 December she left Batavia for Italy, which was also still neutral. She called at Sabang, Aden and Port Said before arriving on 21 December in Genoa, where she spent Christmas 1939 and New Year 1940. She left Genoa on 10 January for the East Indies, calling at Suez, Aden and Sabang before reaching Batavia on 1 February.[9]

In May 1940 Germany conquered the Netherlands in one week and the Dutch monarchy and government evacuated to London. Germany captured KRL's managing director Willem Ruys, and the company transferred the registration of its ships including Slamat from Rotterdam to Batavia.[10]

On 6 July KRL's Indrapoera left Batavia for Surabaya in eastern Java, and on the 19th Slamat followed her. Then the two liners sailed to the Philippines, which were then neutral. Indrapoera sailed ahead, leaving Surabaya on 26 July and reaching Manila on the 31st. Slamat followed three days behind her, reaching Manila on 3 August. By then Indrapoera had already left for Australia, and the next day Slamat followed. Each liner called at Thursday Island, Queensland before reaching Sydney Harbour, Indrapoera on 13 August and Slamat on the 17th.[11] There they joined two other Dutch ocean liners; Stoomvaart-Maatschappij Nederland's 16,287 GRT Christiaan Huygens and Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij's Nieuw Holland, which between them embarked 4,315 Australian troops. On 12 September the Dutch ships left Sydney for Fremantle in Western Australia, where they formed Convoy US 5, which left Fremantle on 22 September and reached Suez on 12 October. Indrapoera and Slamat continued through the Suez Canal, called at Port Said and on 17 October reached Haifa in Palestine.[9]

In September 1940 Italy invaded Egypt, where British and Empire forces now needed reinforcement from the Dominions and Empire. From now on a number of Dutch troop ships concentrated on bringing British Empire troops across the Indian Ocean to the Near East. Indrapoera and Slamat left Haifa on 21 October, reached Port Said the next day, and then passed through the Suez Canal. For the next six months the two KRL ships operated in the Indian Ocean, bringing British Empire troops from India and Ceylon to Egypt.[9][11]

Indrapoera and Slamat spent Christmas 1940 and New Year 1941 in Bombay. On 14 January 1941 they reached Colombo to take part in Convoy US 8 to Suez.[9][11] This was a huge troop movement: seven British and five Dutch troop ships, accompanied by two British cargo ships. The other Dutch ships were Christiaan Huygens, SMN's Johan de Witt and KPM's Nieuw Zeeland. Among the British ships was Shaw, Savill & Albion Line's flagship QSMV Dominion Monarch, which at 27,155 GRT was the largest liner in the Indian Ocean. US 8 left Colombo on 16 January and reached Suez on the 28th.[12]

After US 8, Indrapoera and Slamat continued to operate in the Indian Ocean until April 1941. Then Indrapoera headed via Durban to the Caribbean and United States,[11] but Slamat returned to the Mediterranean.[9]

Convoy to and from Nauplia

In April 1941 Germany and Italy invaded Yugoslavia and Greece. After 10 days of fierce fighting the British Empire started to plan the evacuation of 60,000 troops from Greece.

Slamat had been spending the month making shuttle trips between Suez and Port Sudan, but by 23 April she was in the Mediterranean Sea and on the 24th she was in Convoy AG 14 from Alexandria to Greece. When the convoy reached Greek waters, it split to reach different embarkation points.[13] Slamat and another troop ship, the British-India Line-managed Khedive Ismail, were ordered with the cruiser HMS Calcutta and a number of destroyers to Nauplia[14] and Tolon on the Argolic Gulf in the eastern Peloponnese.

Before their arrival another troopship had grounded in Nauplia Bay, blocking ship access to the port. An air attack had turned her into a total loss.[15] Ships would now have to anchor in the bay, where boats would bring troops out to them from the shore. En route to Nauplia Slamat's group of ships was bombed and her superstructure was heavily damaged.

.jpg)

On the evening of 26 April three cruisers, four destroyers and Khedive Ismail and Slamat were in the Bay of Nauplia. The only available tenders were one landing craft, local caïques and the ships' own boats. Two cruisers and two destroyers embarked nearly 2,500 troops, but the slow rate of embarkation meant that Khedive Ismail did not get its turn and did not embark any.[13]

At 0300 hrs Calcutta ordered all ships to sail, but Slamat disobeyed and continued embarking troops. Calcutta and Khedive Ismail sailed at 0400 hrs; Slamat followed at 0415 hrs, by which time she had embarked about 500 troops: about half her capacity.[14]

Loss of Slamat, Diamond and Wryneck

The convoy steamed south down the Argolic Gulf, until at 0645[13] or 0715 hrs[14] Luftwaffe aircraft attacked it: first Bf 109 fighters, then Ju 87 dive bombers and Ju 88 and Do 17 bombers.[13] A 250 kg (550 lb) bomb exploded between Slamat's bridge and forward funnel, setting her afire. Her water system became disabled, hampering her crew's ability to fight the fire. Another bomb also hit her and she listed to starboard.[13]

Slamat's Master, Tjalling Luidinga, gave the order to abandon ship. The bombing and fire had destroyed some of her lifeboats and life rafts, and her remaining boats and rafts were launched under a second Stuka attack.[16] The destroyer HMS Hotspur reported seeing four bombs hit Slamat. Two lifeboats capsized; one from overloading and another when, in the midst of transferring survivors, Diamond had to speed away from her to evade an air attack. Some aircraft machine-gunned survivors in the water.[13]

The rest of the convoy kept moving, while Calcutta rescued some survivors and ordered the destroyer Diamond to rescue more. At 0815 hrs Diamond was still rescuing survivors and still under attack. At 0916 hrs three destroyers from Crete reinforced the convoy, so Calcutta sent one of them, HMS Wryneck, to assist Diamond. At 0925 hrs Diamond reported that she had rescued most of the survivors and was heading for Souda Bay.[13] Wryneck reached Diamond about 1000 hrs[13] and requested aircraft cover at 1025 hrs.[14]

Diamond accompanied by Wryneck returned to Slamat, arriving about 1100 hrs. They found two lifeboats from Slamat and rescued their occupants. Slamat was afire from stem to stern, and Diamond fired a torpedo at her port side that sank her in a coup de grâce.[13][16] By now Diamond carried about 600 of Slamat's survivors, including Captain Luidinga.[13]

About 1315 hrs a Staffel of Ju 87 bombers came out of the sun in a surprise attack on the two destroyers. Two bombs damaged Diamond, destroyed both of her lifeboats and sank her in eight minutes. Three bombs hit Wryneck; she capsized to port and sank in 10–15 minutes. Wryneck launched her whaler and each destroyer launched her three Carley floats.[13] Several men in the Carley floats died either from wounds or from drowning in the swell.[13]

Rescues and casualties

Wryneck's Commissioned Engineer, Maurice Waldron, took command of her whaler and she set off east past Cape Maleas, towing two Carley floats and their occupants. In the evening the wind increased, causing the floats to strike the boat, so Waldron reluctantly cast them adrift.[13]

_IWM_FL_013646.jpg)

After 1900 hrs on 27 April the Vice Admiral, Light Forces, Henry Pridham-Wippell, became concerned that Diamond had not returned to Souda Bay and was not answering radio signals. Wryneck had been ordered to keep radio silence so no attempt was made to radio her.[17] Pridham-Wippell sent the destroyer HMS Griffin to the position where Slamat had been lost. She found 14 survivors in two Carley floats that night, more floats and another four survivors in the morning, and took the survivors to Crete.[13]

The last living survivor from Slamat,[18] Royal Army Service Corps veteran George Dexter, states that after Wryneck was sunk he and three other men were rescued by the cruiser HMS Orion.[19]

Survivors in Wryneck's whaler reached Crete in three stages. On 28 April they aimed for the island of Milos in the Aegean Sea, but were too exhausted so they landed at Ananes Rock, about 13 nautical miles (24 km) southeast of Milos. There they met a caïque full of Greek refugees and British soldiers evacuated from Piraeus, who were sheltering by day and sailing only by night to avoid detection. In the evening everyone left Ananes and headed south for Crete, with most people in the caïque and five being towed in the whaler. On 29 April the caïque sighted a small landing craft that had left Porto Rafti near Athens. She took aboard everyone from the caïque and whaler, and the next day they reached Souda Bay.[13]

Nearly 1,000 people were killed in the loss of Slamat, Diamond and Wryneck. Of the 500 or so soldiers that Slamat embarked, eight survived.[17] Of her complement of 193 crew and 21 Australian and New Zealand DEMS gunners and NZEF Medical Corps,[20] 11 survived. Of Diamond's 166 complement, 20 survived. Of Wryneck's 106 crew, 27 survived.[16]

Monuments

In August 1946 Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands wrote to Captain Luidinga's widow, expressing her sympathy for her husband's death, gratitude for his war service and commending him as een groot zoon van ons zeevarend volk ("a great son of our seafaring people").[16]

British and Commonwealth troops and naval personnel who were lost in the sinking of Slamat, Diamond and Wryneck are named on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission's Athens Memorial in Phaleron War Cemetery at Palaio Faliro southeast of Athens.[21] Royal Navy personnel are also commemorated in Britain on the Royal Navy monuments at Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth. George Dexter commissioned a monument to all the service personnel lost when the three ships were sunk. It is in The Royal British Legion Club, Shard End, Birmingham.[19]

In 2011 a monument commemorating victims from all three ships was made by the Dutch sculptor Nicolas van Ronkenstein. It was installed in the Sint-Laurenskerk ("St Lawrence Church"), Rotterdam and formally unveiled on the 70th anniversary of the disaster, 27 April.[16]

On 27 June 2012 the current HMS Diamond hosted a wreath-laying ceremony at the position where Slamat was sunk. Participants included Diamond's commander, descendants of some of the dead from the Netherlands and New Zealand, and the Commander in Chief of the Hellenic Navy.[22]

References

- ↑ Allen, Tony (8 November 2013). "SS Slamat (+1941)". The Wreck Site. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ Lloyd's Register, Steamers & Motorships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1934. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 Harnack 1938, p. 567.

- 1 2 3 Talbot-Booth 1942, p. 353.

- 1 2 Lloyd's Register, Steamers & Motorships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1930. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ Talbot-Booth 1942, pp. 353, 526.

- ↑ Lloyd's Register, Steamers & Motorships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1931. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ "ss. Slamat (1) 1924". Scheepsafbeeldingen. Bert van Galen. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hague, Arnold. "Slamat". Ship Movements. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ Lloyd's Register, Steamers & Motorships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1940. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Hague, Arnold. "Indrapoera". Ship Movements. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ Hague, Arnold. "Convoy US.8". Shorter Convoy Series. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "The sinking of the Slamat, April 27th 1941. Operation Demon". Dutch Passenger Ships: Willem Ruys, Sibajak, Slamat, Indrapoera, Insulinde, Patria. 4 November 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Report on Evacuation of British Troops from Greece, April, 1941". Supplement to The London Gazette (38293). 19 May 1948. p. 3052. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ "Report on Evacuation of British Troops from Greece, April, 1941". Supplement to The London Gazette (38293). 19 May 1948. p. 3047. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 van Lierde, Eduard. "Slamat Commemoration". Koninklijke Rotterdamsche Lloyd Te Oudehorne. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- 1 2 "Report on Evacuation of British Troops from Greece, April, 1941". Supplement to The London Gazette (38293). 19 May 1948. p. 3053. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ Chadwick, Edward (2009). "Move over, Clooney, meet George Dexter". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- 1 2 Richardson, Andy (5 November 2013). "Ships I was on were BOTH sunk on the same day – and I lived to tell tale". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ "SS Slamat Documentary". KRL Museum. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ "Phaleron War Cemetery". Cemetery details. Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

- ↑ "HMS Diamond pays tribute to wartime victims". Royal Navy. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

Sources and further reading

- Bezemer, K.W.L. (1987). Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Koopvaardij in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 90-100-6040-3.

- Harnack, Edwin P (1938) [1903]. All About Ships & Shipping (7th ed.). London: Faber and Faber. p. 567.

- Luidinga, Frans (1995). Het scheepsjournaal van Tjalling Luidinga 1890–1941: gezagvoerder bij de Rotterdamsche Lloyd (in Dutch). self-published. ISBN 9789080246126.

- Talbot-Booth, E.C. (1936). Ships and the Sea (Third ed.). London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co. Ltd. pp. 353, 526.

Coordinates: 37°01′N 23°10′E / 37.02°N 23.17°E