Succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit C

Succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit C, also known as succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b560 subunit, mitochondrial, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SDHC gene.[5] This gene encodes one of four nuclear-encoded subunits that comprise succinate dehydrogenase, also known as mitochondrial complex II, a key enzyme complex of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and aerobic respiratory chains of mitochondria. The encoded protein is one of two integral membrane proteins that anchor other subunits of the complex, which form the catalytic core, to the inner mitochondrial membrane. There are several related pseudogenes for this gene on different chromosomes. Mutations in this gene have been associated with paragangliomas. Alternatively spliced transcript variants have been described.[6]

Structure

The gene that codes for the SDHC protein is nuclear, even though the protein is located in the inner membrane of the mitochondria. The location of the gene in humans is on the first chromosome at q21. The gene is partitioned in 6 exons. The SDHC gene produces an 18.6 kDa protein composed of 169 amino acids.[7][8]

The SDHC protein is one of the two transmembrane subunits of the four-subunit succinate dehydrogenase (Complex II) protein complex that resides in the inner mitochondrial membrane. The other transmembrane subunit is SDHD. The SDHC/SDHD dimer is connected to the SDHB electron transport subunit which, in turn, is connected to the SDHA subunit.[9]

Function

The SDHC protein is one of four nuclear-encoded subunits that comprise succinate dehydrogenase, also known as Complex II of the electron transport chain, a key enzyme complex of the citric acid cycle and aerobic respiratory chains of mitochondria. The encoded protein is one of two integral membrane proteins that anchor other subunits of the complex, which form the catalytic core, to the inner mitochondrial membrane.[6]

SDHC forms part of the transmembrane protein dimer with SDHD that anchors Complex II to the inner mitochondrial membrane. The SDHC/SDHD dimer provides binding sites for ubiquinone and water during electron transport at Complex II. Initially, SDHA oxidizes succinate via deprotonation at the FAD binding site, forming FADH2 and leaving fumarate, loosely bound to the active site, free to exit the protein. The electrons derived from succinate tunnel along the [Fe-S] relay in the SDHB subunit until they reach the [3Fe-4S] iron sulfur cluster. The electrons are then transferred to an awaiting ubiquinone molecule at the Q pool active site in the SDHC/SDHD dimer. The O1 carbonyl oxygen of ubiquinone is oriented at the active site (image 4) by hydrogen bond interactions with Tyr83 of SDHD. The presence of electrons in the [3Fe-4S] iron sulphur cluster induces the movement of ubiquinone into a second orientation. This facilitates a second hydrogen bond interaction between the O4 carbonyl group of ubiquinone and Ser27 of SDHC. Following the first single electron reduction step, a semiquinone radical species is formed. The second electron arrives from the [3Fe-4S] cluster to provide full reduction of the ubiquinone to ubiquinol.[10]

Clinical significance

Mutations in this gene have been associated with paragangliomas.[6][11] More than 30 mutations in the SDHC gene have been found to increase the risk of hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma type 3. People with this condition have paragangliomas, pheochromocytomas, or both. An inherited SDHC gene mutation predisposes an individual to the condition, and a somatic mutation that deletes the normal copy of the SDHC gene is needed to cause hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma type 3. Most of the inherited SDHC gene mutations change single amino acids in the SDHC protein sequence or result in a shortened protein. As a result, there is little or no SDH enzyme activity. Because the mutated SDH enzyme cannot convert succinate to fumarate, succinate accumulates in the cell. The excess succinate abnormally stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF), which also builds up in cells. Excess HIF stimulates cells to divide and triggers the production of blood vessels when they are not needed. Rapid and uncontrolled cell division, along with the formation of new blood vessels, can lead to the development of tumors in people with hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma.[12]

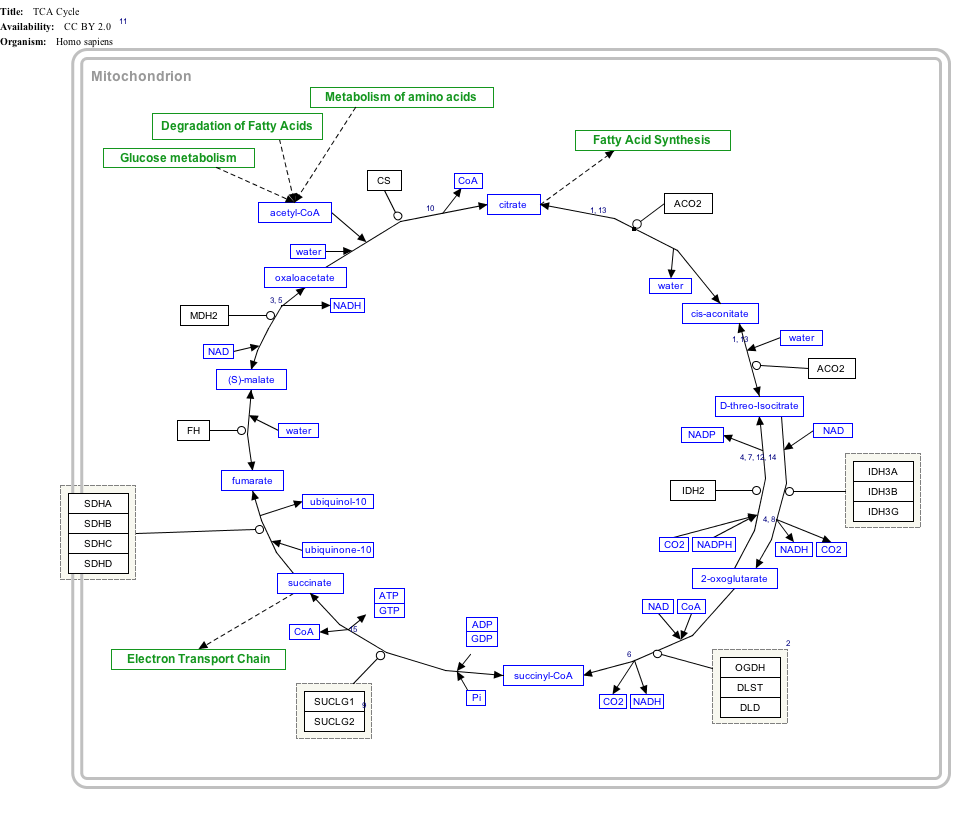

Interactive pathway map

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

|{{{bSize}}}px|alt=TCA Cycle edit]]

TCA Cycle edit

- ↑ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "TCACycle_WP78".

References

- 1 2 3 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000143252 - Ensembl, May 2017

- 1 2 3 GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000058076 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ Hirawake H, Taniwaki M, Tamura A, Kojima S, Kita K (1997). "Cytochrome b in human complex II (succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase): cDNA cloning of the components in liver mitochondria and chromosome assignment of the genes for the large (SDHC) and small (SDHD) subunits to 1q21 and 11q23". Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 79 (1-2): 132–8. PMID 9533030. doi:10.1159/000134700.

- 1 2 3 "Entrez Gene: succinate dehydrogenase complex".

- ↑ Zong NC, Li H, Li H, Lam MP, Jimenez RC, Kim CS, Deng N, Kim AK, Choi JH, Zelaya I, Liem D, Meyer D, Odeberg J, Fang C, Lu HJ, Xu T, Weiss J, Duan H, Uhlen M, Yates JR, Apweiler R, Ge J, Hermjakob H, Ping P (October 2013). "Integration of cardiac proteome biology and medicine by a specialized knowledgebase". Circulation Research. 113 (9): 1043–53. PMC 4076475

. PMID 23965338. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301151.

. PMID 23965338. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301151. - ↑ "SDHC - Succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b560 subunit, mitochondrial". Cardiac Organellar Protein Atlas Knowledgebase (COPaKB).

- ↑ Sun, F; Huo, X; Zhai, Y; Wang, A; Xu, J; Su, D; Bartlam, M; Rao, Z (1 July 2005). "Crystal structure of mitochondrial respiratory membrane protein complex II.". Cell. 121 (7): 1043–57. PMID 15989954. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.025.

- ↑ Horsefield, R; Yankovskaya, V; Sexton, G; Whittingham, W; Shiomi, K; Omura, S; Byrne, B; Cecchini, G; Iwata, S (17 March 2006). "Structural and computational analysis of the quinone-binding site of complex II (succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase): a mechanism of electron transfer and proton conduction during ubiquinone reduction.". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (11): 7309–16. PMID 16407191. doi:10.1074/jbc.m508173200.

- ↑ Niemann S, Müller U, Engelhardt D, Lohse P (July 2003). "Autosomal dominant malignant and catecholamine-producing paraganglioma caused by a splice donor site mutation in SDHC". Hum. Genet. 113 (1): 92–4. PMID 12658451. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-0938-0.

- ↑ "SDHC". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

Further reading

- Bayley JP, Weiss MM, Grimbergen A, et al. (2009). "Molecular characterization of novel germline deletions affecting SDHD and SDHC in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma patients.". Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 16 (3): 929–37. PMID 19546167. doi:10.1677/ERC-09-0084.

- Pasini B, McWhinney SR, Bei T, et al. (2008). "Clinical and molecular genetics of patients with the Carney-Stratakis syndrome and germline mutations of the genes coding for the succinate dehydrogenase subunits SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD.". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 16 (1): 79–88. PMID 17667967. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201904.

- Gaal J, Burnichon N, Korpershoek E, et al. (2010). "Isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations are rare in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas.". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95 (3): 1274–8. PMID 19915015. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2170.

- Milosevic D, Lundquist P, Cradic K, et al. (2010). "Development and validation of a comprehensive mutation and deletion detection assay for SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD.". Clin. Biochem. 43 (7-8): 700–4. PMC 3419008

. PMID 20153743. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.01.016.

. PMID 20153743. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.01.016. - Bonache S, Martínez J, Fernández M, et al. (2007). "Single nucleotide polymorphisms in succinate dehydrogenase subunits and citrate synthase genes: association results for impaired spermatogenesis.". Int. J. Androl. 30 (3): 144–52. PMID 17298551. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2006.00730.x.

- Cascán A, Lápez-Jiménez E, Landa I, et al. (2009). "Rationalization of genetic testing in patients with apparently sporadic pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma.". Horm. Metab. Res. 41 (9): 672–5. PMID 19343621. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1202814.

- Goto Y, Ando T, Naito M, et al. (2006). "No association of an SDHC gene polymorphism with gastric cancer.". Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 7 (4): 525–8. PMID 17250422.

- Cascán A, Pita G, Burnichon N, et al. (2009). "Genetics of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma in Spanish patients.". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94 (5): 1701–5. PMID 19258401. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-2756.

- Boedeker CC, Neumann HP, Maier W, et al. (2007). "Malignant head and neck paragangliomas in SDHB mutation carriers.". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 137 (1): 126–9. PMID 17599579. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2007.01.015.

- Gill AJ, Benn DE, Chou A, et al. (2010). "Immunohistochemistry for SDHB triages genetic testing of SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD in paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes.". Hum. Pathol. 41 (6): 805–14. PMID 20236688. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2009.12.005.

- Ricketts C, Woodward ER, Killick P, et al. (2008). "Germline SDHB mutations and familial renal cell carcinoma.". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100 (17): 1260–2. PMID 18728283. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn254.

- McWhinney SR, Pasini B, Stratakis CA (2007). "Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors and germ-line mutations.". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (10): 1054–6. PMID 17804857. doi:10.1056/NEJMc071191.

- Eng C, Kiuru M, Fernandez MJ, Aaltonen LA (2003). "A role for mitochondrial enzymes in inherited neoplasia and beyond.". Nat. Rev. Cancer. 3 (3): 193–202. PMID 12612654. doi:10.1038/nrc1013.

- Hermsen MA, Sevilla MA, Llorente JL, et al. (2010). "Relevance of germline mutation screening in both familial and sporadic head and neck paraganglioma for early diagnosis and clinical management.". Cell. Oncol. 32 (4): 275–83. PMID 20208144. doi:10.3233/CLO-2009-0498.

- Brií¨re JJ, Favier J, El Ghouzzi V; et al. (2005). "Succinate dehydrogenase deficiency in human.". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62 (19-20): 2317–24. PMID 16143825. doi:10.1007/s00018-005-5237-6.

- Mannelli M, Castellano M, Schiavi F, et al. (2009). "Clinically guided genetic screening in a large cohort of italian patients with pheochromocytomas and/or functional or nonfunctional paragangliomas.". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94 (5): 1541–7. PMID 19223516. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-2419.

- Richalet JP, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Peyrard S, et al. (2009). "A role for succinate dehydrogenase genes in low chemoresponsiveness to hypoxia?". Clin. Auton. Res. 19 (6): 335–42. PMID 19768395. doi:10.1007/s10286-009-0028-z.

- Pigny P, Cardot-Bauters C, Do Cao C, et al. (2009). "Should genetic testing be performed in each patient with sporadic pheochromocytoma at presentation?". Eur. J. Endocrinol. 160 (2): 227–31. PMID 19029228. doi:10.1530/EJE-08-0574.

- Korpershoek E, Van Nederveen FH, Dannenberg H, et al. (2006). "Genetic analyses of apparently sporadic pheochromocytomas: the Rotterdam experience.". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1073: 138–48. PMID 17102080. doi:10.1196/annals.1353.014.

- Wang L, McDonnell SK, Hebbring SJ, et al. (2008). "Polymorphisms in mitochondrial genes and prostate cancer risk.". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 17 (12): 3558–66. PMC 2750891

. PMID 19064571. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0434.

. PMID 19064571. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0434.

External links

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.