S-125 Neva/Pechora

| S-125 Neva/Pechora NATO reporting name: SA-3 Goa | |

|---|---|

|

Peruvian Air Force Pechora | |

| Type | Strategic SAM system |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1961[1]–present |

| Used by | See list of present and former operators |

| Wars | Yom Kippur War, Kosovo War, Iran–Iraq War, Gulf War, Angolan Civil War, Syrian Civil War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Almaz Central Design Bureau |

| Designed | 1960s |

| Manufacturer | JSC Defense Systems (Pechora-M) |

| Produced | 1961–present |

| Variants | Neva, Pechora, Volna, Neva-M, Neva-M1, Volna-M, Volna-N, Volna-P, Pechora 2, Pechora 2M, Newa SC, Pechora-M |

The S-125 Neva/Pechora (Russian: С-125 "Нева"/"Печора", NATO reporting name SA-3 Goa) Soviet surface-to-air missile system was designed by Aleksei Mihailovich Isaev to complement the S-25 and S-75. It has a shorter effective range and lower engagement altitude than either of its predecessors and also flies slower, but due to its two-stage design it is more effective against more maneuverable targets. It is also able to engage lower flying targets than the previous systems, and being more modern it is much more resistant to ECM than the S-75. The 5V24 (V-600) missiles reach around Mach 3 to 3.5 in flight, both stages powered by solid fuel rocket motors. The S-125, like the S-75, uses radio command guidance. The naval version of this system has the NATO reporting name SA-N-1 Goa and original designation M-1 Volna (Russian Волна – wave).

Operational history

Soviet Union

The S-125 was first deployed between 1961 and 1964 around Moscow, augmenting the S-25 and S-75 sites already ringing the city, as well as in other parts of the USSR. In 1964, an upgraded version of the system, the S-125M "Neva-M" and later S-125M1 "Neva-M1" was developed. The original version was designated SA-3A by the US DoD and the new Neva-M named SA-3B and (naval) SA-N-1B. The Neva-M introduced a redesigned booster and an improved guidance system. The SA-3 was not used against U.S. forces in Vietnam, because the Soviets feared that China (after the souring of Sino-Soviet relations in 1960), through which most, if not all of the equipment meant for North Vietnam had to travel, would try to copy the missile.

Angola

The FAPA-DAA acquired a significant number of SA-3s, and these were encountered during the first strike flown by SAAF Mirage F.1s against targets in Angola ever - in June 1980. While the SAAF reported two aircraft were damaged by SAMs during this action, Angola claimed to have shot down four.[2]

On 7 June 1980, while attacking SWAPO's Tobias Haneko Training Camp during Operation Sceptic (Smokeshell), SAAF Major Frans Pretorius and Captain IC du Plessis, both flying Mirage F.1s, were hit by SA-3s. Pretorius's aircraft was hit in a fuel line and he had to perform a deadstick landing at AFB Ondangwa. Du Plessis's aircraft sustained heavier damage and had to divert to Ruacana forward airstrip, where he landed with only the main undercarriage extended. Both aircraft were repaired and returned to service.[3]

Middle East

The Soviets supplied several SA-3s to the Arab states in the late 1960s and 1970s, most notably Egypt and Syria. The SA-3 saw extensive action during the War of Attrition and the Yom Kippur War. During the latter, the SA-3, along with the SA-2 and SA-6, formed the backbone of the Egyptian air defence network. In Egypt, March–July 1970 Soviet battalions of S-125 17 Shooting (35 missiles) shot down 9 Israeli and Egyptian planes.[4][5][6][7] Israel recognized the 5 in 1970 and in 1973 another 6[7]

Syria deployed it for the first time during the 1973 Yom Kippur War and also during the 1982 Lebanon war. In fighting over the Beqaa Valley, however, the IAF managed to neutralize the SAM threat by launching Operation Mole Cricket 19, in which several SA-3 batteries, along with SA-2s and SA-6s, were destroyed in a single day.

Iraq

A USAF F-16 (serial 87-257) was shot down on January 19, 1991, during Operation Desert Storm. The aircraft was struck by an SA-3 just south of Baghdad. The pilot, Major Jeffrey Scott Tice, ejected safely but became a POW as the ejection took place over Iraq. It was the 8th combat loss and the first daylight raid over Baghdad.[8]

On the opening night of Desert Storm, on 17 January 1991, a B-52G was damaged by a missile. Different versions of this engagement are told. It could have been a S-125 or a 2K12 Kub while other versions report a MiG-29 allegedly fired a Vympel R-27R missile and damaged the B-52G.[9] However, the U.S. Air Force disputes these claims, stating the bomber was actually hit by friendly fire, an AGM-88 High-speed, Anti-Radiation Missile (HARM) that homed on the fire-control radar of the B-52's tail gun; the jet was subsequently renamed In HARM's Way.[10] Shortly following this incident, General George Lee Butler announced that the gunner position on B-52 crews would be eliminated, and the gun turrets permanently deactivated, commencing on 1 October 1991.[11]

FR Yugoslavia

A Yugoslav Army 250th Air Defense Missile Brigade 3rd battery equipped with S-125 system managed to shoot down an F-117 Nighthawk stealth attack aircraft on March 27, 1999 during the Kosovo War (the only recorded downing of a stealth aircraft) near village Budjanovci, about 45 km from Belgrade. It was also used to shoot down a NATO F-16 fighter on May 2 (its pilot; Lt. Col David L. Goldfein, the commander of 555th Fighter Squadron, managed to eject and was later rescued by a combat search-and-rescue (CSAR) mission).[12][13]

During the war, different Yugoslav SAM sites and possibly the SA-3 also shot down some NATO UAVs.

"The war (in Kosovo) proved that a competent opponent can improvise ways to overcome superior weaponry because every technology has weaknesses that can be identified and exploited," the jury is still out even on real damage to Serbian military infrastructure, the fact remains that SAM sites forced NATO planes to fly higher and be less effective than they would have been without these defences.[14]

Syrian Civil War

On 17 March 2015, a US MQ-1 Predator drone was shot down by a Syrian Air Defense Force S-125 missile while on intelligence flight near the coastal town of Latakia.[15]

In December 2016, ISIS forces captured three SA-3 launchers after they retook Palmyra from Russian and Syrian government troops.[16]

Description

The S-125 is somewhat mobile, an improvement over the S-75 system. The missiles are typically deployed on fixed turrets containing two or four but can be carried ready-to-fire on ZIL trucks in pairs. Reloading the fixed launchers takes a few minutes.

Missile

| V-600 | |

|---|---|

|

V-600 missiles on the S-125 quadruple launcher. | |

| Type | Surface-to-air missile |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Production history | |

| Variants | V-600, V-601 |

| Specifications (V-601[17]) | |

| Weight | 953 kg |

| Length | 6.09 m |

| Diameter | 375 mm |

| Warhead | Frag-HE |

| Warhead weight | 60 kg |

Detonation mechanism | Proximity fuse[18] |

|

| |

| Wingspan | 2.2 m |

| Propellant | Solid propellant rocket motor |

Operational range | 35 kilometres (22 mi) |

| Flight altitude | 18,000 metres (59,000 ft) |

Guidance system | RF CLOS |

The S-125 system uses 2 different missile versions. The V-600 (or 5V24) had the smallest warhead with only 60 kg of high explosive. It had a range of about 15 km.

The later version is named V-601 (or 5V27). It has a length of 6.09 m, a wing span of 2.2 m and a body diameter of 0.375 m. This missile weighs 953 kg at launch, and has a 70 kg warhead containing 33 kg of HE and 4,500 fragments. The minimum range is 3.5 km, and the maximum is 35 km (with the Pechora 2A). The intercept altitudes are between 100 m and 18 km.[17]

The S-125M (1970) system uses 5V27. The intercept altitudes are between 20 m and 14 km. The minimum range is 2.5 km, and the maximum is 22 km[6][7] The S-125M1 (1978) system uses 5V27D. In the early 1980s established for each system 1-2 radar simulator (against antiradar missiles assigned)[7]

Radars

The launchers are accompanied by a command building or truck and three primary radar systems:

- P-15 "Flat Face" or P-15M(2) "Squat Eye" 380 kW C-band target acquisition radar (also used by the SA-6 and SA-8, range 250 km/155 miles)

- SNR-125 "Low Blow" 250 kW I/D-band tracking, fire control and guidance radar (range 40 km/25 miles, second mode 80 km/50 miles)

- PRV-11 "Side Net" E-band height finder (also used by SA-2, SA-4 and SA-5, range 28 km/17 miles, max height 32 km/105,000 ft)

"Flat Face"/"Squat Eye" is mounted on a van ("Squat Eye" on a taller mast for better performance against low-altitude targets also an IFF [Identifies Friend or Foe]), "Low Blow" on a trailer and "Side Net" on a box-bodied trailer.

Variants and upgrades

Naval version

Work on a naval version M-1 Volna (SA-N-1) started in 1956, along with work on a land version. It was first mounted on a rebuilt Kotlin class destroyer (Project 56K) Bravyi and tested in 1962. In the same year, the system was accepted. The basic missile was a V-600 (or 4K90) (range: from 4 to 15 km, altitude: from 0.1 to 10 km). Fire control and guidance is carried out by 4R90 Yatagan radar, with five parabolic antennas on a common head. Only one target can be engaged at a time (or two, for ships fitted with two Volna systems). In case of emergency, Volna could be also used against naval targets, due to short response time.

The first launcher type was the two-missile ZIF-101, with a magazine for 16 missiles. In 1963 an improved two-missile launcher, ZIF-102, with a magazine for 32 missiles, was introduced to new ship classes. In 1967 Volna systems were upgraded to Volna-M (SA-N-1B) with V-601 (4K91) missiles (range: 4–22 km, altitude: 0.1–14 km).

In 1974 - 1976 some systems were modernized to Volna-P standard, with an additional TV target tracking channel and better resistance to jamming. Later, improved V-601M missiles were introduced, with lower minimal attack altitude against aerial targets (system Volna-N).

Some Indian frigates also carry the M-1 Volna system.

Modern upgrades

Since Russia replaced all of its S-125 sites with SA-10 and SA-12 systems, they decided to upgrade the S-125 systems being removed from service to make them more attractive to export customers.

- Released in 2000, the Pechora-2 version features better range, multiple target engagement ability and a higher probability of kill (PK). The launcher is moved onto a truck allowing much shorter relocation times.

- It is also possible to fire the Pechora-2M system against cruise missiles. Deployment time 25 minutes, protected from the active interference, and anti-radiation missiles (total in practical shooting)[19][20]

Early warning radar is replaced by anti-stealth[21][22] radar Caste 2e2, defeat the purpose of by range 2.5–32 km, defeat the purpose of in height - 0.02–20 km, distance rocket launchers from the control center 10 kilometers.[23] Speed up to 1000 m/s (target), Used rocket 5V27DE,[24] by weight the warhead + 50% range of flight splinters + 350%.[25] Probability of hitting the target 1st rocket: at a distance up to 25 km - 0,72-0,99, detection range with EPR = 2 m. sq about 100 km, with the objectives of the EPR = 0.15 m. sq about 50 km, with no interference. When using active jamming - 40 km.[26] ADMS "Pechora-2M" has the ability to interfacing with higher level command post and radar remote using telecode channels. Is equally effective at any time during the day and at night (optical location, daytime and nighttime, and also thermal imager [up to 30 km of night and 60 km of day[6]]),[27][28] for such a system, the detection range of an aircraft such as F-16 is 30 km away.[29] Is possible to use two radar pointing missiles, it allows the client to simultaneously work on two goals.[26] For the purpose with a height of 350 meters detection range of 40 km.[6]

In 1999, a Russian-Belarusian financial-industrial consortium called Oboronitelnye Sistemy (Defense Systems) was awarded a contract to overhaul Egypt's S-125 SAM system. These refurbished weapons have been reintroduced as the S-125 Pechora 2M.[30]

- In 2001, Poland began offering an upgrade to the S-125 known as the Newa SC. This replaced many analogue components with digital ones for improved reliability and accuracy. This upgrade also involves mounting the missile launcher on a WZT-1 tank chassis (a TEL), greatly improving mobility and also adds IFF capability and data links. Radar is mounted on an 8-wheeled heavy truck chassis (formerly used for Scud launchers).

Serbian modifications include terminal/camera homing from radar base.

Cuba also developed a similar upgrade to the Polish one, which was displayed in La Habana in 2006.[31]

- Later the same year, the Russian version was upgraded again to the Pechora-M which upgraded almost all aspects of the system - the rocket motor, radar, guidance, warhead, fuse and electronics. There is an added laser/infra-red tracking device to allow launching of missiles without the use of the radar.

There is also a version of the S-125 available from Russia with the warhead replaced with telemetry instrumentation, for use as target drones.

- In October 2010, Ukrainian Aerotechnica announced a modernized version of S-125 named S-125-2D Pechora.[32]

Operators

Current operators

-

Algeria[33]

Algeria[33] -

Angola

Angola -

Armenia

Armenia -

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan -

Bulgaria

Bulgaria -

Burma[34]

Burma[34] -

Cuba

Cuba -

Egypt[34] No less than 50[35][36] Pechora 2M in 2012[37][38] + ≈120[35]

Egypt[34] No less than 50[35][36] Pechora 2M in 2012[37][38] + ≈120[35] -

Ethiopia[35]

Ethiopia[35] -

Georgia

Georgia -

India

India -

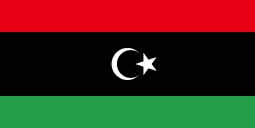

Libya[34]

Libya[34] -

Moldova

Moldova -

Mongolia Pechora-2M[35][39]

Mongolia Pechora-2M[35][39] -

Mozambique

Mozambique -

North Korea 140 batteries[40]

North Korea 140 batteries[40] -

Peru

Peru -

Poland 12 Newa SC[41]

Poland 12 Newa SC[41] -

Serbia 12 surface-to-air missile systems, with 32 rocket launchers (being modernized with IR camera - Range finder)

Serbia 12 surface-to-air missile systems, with 32 rocket launchers (being modernized with IR camera - Range finder) -

Syria[34] 148 Pechora[42] + 12Pechora-2M[43]

Syria[34] 148 Pechora[42] + 12Pechora-2M[43] -

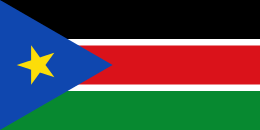

South Sudan[44]

South Sudan[44] -

Tanzania

Tanzania -

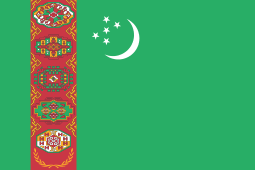

Turkmenistan[34]

Turkmenistan[34] -

Kazakhstan Pechora-2TM[45]

Kazakhstan Pechora-2TM[45] -

Ukraine[46]

Ukraine[46] -

Venezuela Pechora-2M 11.[47][48] Ordered 11[48] new systems, delivered 1 system in 2011 (up to 8 launchers)[49]

Venezuela Pechora-2M 11.[47][48] Ordered 11[48] new systems, delivered 1 system in 2011 (up to 8 launchers)[49] -

Vietnam[34][50] Pechora-2TM version[51]

Vietnam[34][50] Pechora-2TM version[51] -

Yemen

Yemen -

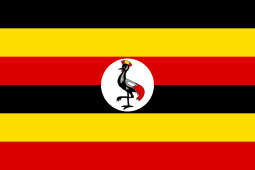

Uganda

Uganda -

Zambia

Zambia

Former operators

-

Afghanistan

Afghanistan -

Cambodia (scrapped in 2005)[52]

Cambodia (scrapped in 2005)[52] -

Czechoslovakia (1973 - retired in the Czech Republic in 2002) [53]

Czechoslovakia (1973 - retired in the Czech Republic in 2002) [53] -

East Germany

East Germany -

Ecuador P-15 "Flat Face" radar Unknown service

Ecuador P-15 "Flat Face" radar Unknown service -

Finland (retired in 1990s)

Finland (retired in 1990s) -

Hungary (in service 1978–1995)[54]

Hungary (in service 1978–1995)[54] -

.svg.png) Iraq (destroyed 2003)

Iraq (destroyed 2003) -

Islamic State Three launchers captured at Palmyra before being destroyed by the United States.[55][16]

Islamic State Three launchers captured at Palmyra before being destroyed by the United States.[55][16] -

Romania (in service 1986–1998)

Romania (in service 1986–1998) -

Russia (retired in 1990s)

Russia (retired in 1990s)

- Missiles used as targets for training. RM-5V27 Pishal (in service as of 2011)

-

Somalia (inoperational by 1992)[56]

Somalia (inoperational by 1992)[56] -

Slovakia (retired in 2001)

Slovakia (retired in 2001) -

South Yemen

South Yemen -

Soviet Union

Soviet Union -

Yugoslavia 14 S-125 batteries with a total of about 60 launchers

Yugoslavia 14 S-125 batteries with a total of about 60 launchers

Gallery of Radars

- P-15 "Flat Face" radar.

S-125 Neva (Pechora)(SA-3 Goa)"Low Blow" radar.

S-125 Neva (Pechora)(SA-3 Goa)"Low Blow" radar. PRV-11 "Side Net" radar.

PRV-11 "Side Net" radar.

References

- ↑ "S-125 SA-3 GOA". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ↑ http://s188567700.online.de/CMS/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=131&Itemid=47

- ↑ Lord, Dick (2000). Vlamgat: The Story of the Mirage F1 in the South African Air Force. Covos-Day. ISBN 0-620-24116-0.

- ↑ Зенитные ракетные войска в войнах во Вьетнаме и на Ближнем Востоке (в период 1965—1973 гг.). М.: Воениздат, 1980. С. 215

- ↑ "Боевое применение зенитной ракетной системы С-125". Военно-патриотический сайт «Отвага» (in Russian). Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Bongo. "Маловысотный ЗРК С-125". Военное обозрение (in Russian). Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- 1 2 3 4 "ЗРК С-125". pvo.guns.ru. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ↑ "Airframe Details for F-16 #87-0257". F-16.net. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ↑ Lake 2004, p. 48.

- ↑ Lake 2004, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Condor 1994, p. 44.

- ↑ Roberts, Chris. "Holloman commander recalls being shot down in Serbia". F-16.net, 7 February 2007. Retrieved: 16 May 2008.

- ↑ Anon. "F-16 Aircraft Database: F-16 Airframe Details for 88-0550". F-16.net. Retrieved: 16 May 2008.

- ↑ Andrew, Martin (2009-06-14). "Revisiting the Lessons of Operation Allied Force". VI (APA-2009-04). Air Power Australia Analyses. ISSN 1832-2433. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- ↑ "air force lost predator was shot down in syria". airforcetimes. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- 1 2 "ISIS has three surface-to-air missile launchers in Syria, US officials say". Fox News. 2016-12-15. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- 1 2 "S-125/Pechora (SA-3 'Goa')". Jane's. 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ http://www.ausairpower.net/APA-S-125-Neva.html

- ↑ ""Печора-2М" стала практически неуязвима для ракет, самонаводящихся по излучению радаров — Сергей Птичкин — Российская газета". Rg.ru. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ↑ ARIC. "Пбп "Пвптпойфемшоще Уйуфенщ" - Пуопчобс Ртпйъчпдуфчеообс Урегйбмйъбгйс Ртедртйсфйк Ипмдйозб". Defensys.ru. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ↑ "-22". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Administrator. "Каста-2-2". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "ЗРК "Печора-2М" - успехи модернизации". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Таджикистан получил зенитно-ракетный комплекс "Печора-2М"". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Вадим, Смирнов. "ЗРК «Печора-2М» - успехи модернизации". Военное обозрение (in Russian). Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- 1 2 "RusArmy.com - "-2"". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "ЗРК Печора-2М: вторая жизнь С-125". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "ЗРК Печора-2М: вторая жизнь С-125". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Россия окружает себя "Печорой"". РИА Новости. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Unique Surface-To-Air Missile Baffles Foreign Military Diplomats In Egypt". Spacewar.com. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ↑ Dr C Kopp, Smaiaa, Smieee, Peng. "Legacy Air Defence System Upgrades". Ausairpower.net. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ↑ "Ukrainian SAM upgrade locks on to launch customers". Jane's Defence Weekly. 2010-10-14. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved 2010-11-05.

- ↑ Administrator. "SA-3 Goa S-125 Neva Pechora ground to air missile system technical data sheet specifications UK | Russia Russian missile system vehicle UK | Russia Russian army military equipment vehicles UK". www.armyrecognition.com. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Sistema antiaéreo Pechora-2M: Un arma eficaz como el Kalashnikov. Vedomosti" [Anti-Air Pechora-2M system: A weapon as effective as the Kalashnikov. Vedomosti] (in Spanish). RIA. 2008-12-26. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "ОАО «Оборонительные системы» рассчитывает на дальнейшее расширение экспортных поставок модернизированного ЗРК «Печора-2М» | Ракетная техника". rbase.new-factoria.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ↑ http://bmpd.livejournal.com/187454.html%5B%5D

- ↑ "Египет показал новую "Печору"". Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ↑ "Белорусско-российские ЗРК «Печора-2М» приняты на вооружение армией Египта". ВПК.name. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ↑ "Defense & Security Intelligence & Analysis: IHS Jane's | IHS". Articles.janes.com. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ↑ "Lenta.ru: Наука и техника: КНДР усилила противовоздушную оборону Пхеньяна". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ The Military Balance 2013. P. 164

- ↑ The International Institute For Strategic Studies IISS The Military Balance 2012. — Nuffield Press, 2012. — С. 349 с.

- ↑ "Trade Registers". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ http://www.janes.com/article/57003/south-sudan-deploys-s-125-sam-system

- ↑ сборник, БАСТИОН: военно-технический. "ВООРУЖЕНИЯ, ВОЕННАЯ ТЕХНИКА, ВОЕННО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЙ СБОРНИК, СОВРЕМЕННОЕ СОСТОЯНИЕ, ИСТОРИЯ РАЗВИТИЯ ОПК, БАСТИОН ВТС, НЕВСКИЙ БАСТИОН, ЖУРНАЛ, СБОРНИК, ВПК, АРМИИ, ВЫСТАВКИ, САЛОНЫ, ВОЕННО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ, НОВОСТИ, ПОСЛЕДНИЕ НОВОСТИ, ВОЕННЫЕ НОВОСТИ, СОБЫТИЯ ФАКТЫ ВПК, НОВОСТИ ОПК, ОБОРОННАЯ ПРОМЫШЛЕННОСТЬ, МИНИСТРЕСТВО ОБОРОНЫ, СИЛОВЫХ СТРУКТУР, КРАСНАЯ АРМИЯ, СОВЕТСКАЯ АРМИЯ, РУССКАЯ АРМИЯ, ЗАРУБЕЖНЫЕ ВОЕННЫЕ НОВОСТИ, ВиВТ, ПВН". bastion-karpenko.ru. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ↑ "Ukrainian ministry of Defence". Міністерство оборони України. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "19.04.12 Египетские ЗРК «Печора-2М» - фото - Военный паритет". www.militaryparitet.com. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- 1 2 "Венесуэльский орешек". ВПК.name. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ↑ "ЦАМТО / Главное / В Венесуэле создан первый позиционный район, где базируется батарея ЗРК "Печора-2М"". Armstrade.org. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ↑ Linder, James B.; Gregor, A. James (1981). United States. Dept. of the Air Force. "The Chinese communist Air Force in the "punitive" war against Vietnam". Air University Review. United States Air Force. XXXIII (6): 72. GGKEY:8Q7C9Z5UADZ. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ saidpvo (2012-03-03). "С-125М-2ТМ "Печора-2ТМ" во Вьетнаме?". Блог "Вестника ПВО". Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ↑ Archived October 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "PL raketový komplet S-125 NĚVA | Fronta.cz". www.fronta.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ↑ Sean O'Connor (2008-10-01). "IMINT & Analysis: Hungarian Strategic Air Defense: A Cold War Case Study". Geimint.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ↑ https://twitter.com/oryxspioenkop/status/808690785403228164

- ↑ "Somalia - Mission, Organization, and Strength". Country-data.com. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

External links

- Description of C-125 on the producer site in Russian

- MissileThreat.com page

- Federation of American Scientists page

- Jane's Defence news on Egyptian S-125 upgrade, April 2006

- Defencetalk on Egyptian S-125 upgrade, October 2006

- S-125 Missile Pictures

- S-125M1 Neva (SA-3b Goa) SAM Simulator

- http://peters-ada.de/neva.htm (in German)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to S-125. |