Luanda

Coordinates: 8°50′18″S 13°14′04″E / 8.83833°S 13.23444°E

| Luanda | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

View of Luanda bay, February 2013 | |

Luanda Location of Luanda in Angola | |

| Coordinates: 8°50′18″S 13°14′4″E / 8.83833°S 13.23444°E | |

| Country |

|

| Province | Luanda |

| Founded | 1576 |

| Area | |

| • City | 113 km2 (44 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,257 km2 (871 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 6 m (20 ft) |

| Population (2014 Census) | |

| • City | 2,825,311 |

| • Density | 25,000/km2 (65,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,107,648 |

| • Urban density | 18,169/km2 (47,060/sq mi) |

| • Metro density | 2,899/km2 (7,510/sq mi) |

| Time zone | +1 |

| Climate | BSh |

Luanda, formerly named São Paulo da Assunção de Loanda, is the capital and largest city in Angola, and the country's most populous and important city, primary port and major industrial, cultural and urban centre. Located on Angola's coast with the Atlantic Ocean, Luanda is both Angola's chief seaport and its administrative centre. It has a metropolitan population of over 6 million. It is also the capital city of Luanda Province, and the world's third most populous Portuguese-speaking city, behind only São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, both in Brazil, and the most populous Portuguese-speaking capital city in the world, ahead of Brasília, Maputo and Lisbon.

The city is currently undergoing a major reconstruction,[1] with many large developments taking place that will alter its cityscape significantly.

History

Portuguese rule

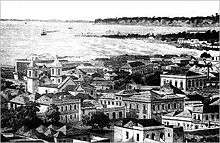

.jpg)

Portuguese explorer Paulo Dias de Novais founded Luanda on 25 January 1576 as "São Paulo da Assumpção de Loanda", with one hundred families of settlers and four hundred soldiers. In 1618, the Portuguese built the fortress called Fortaleza São Pedro da Barra, and they subsequently built two more: Fortaleza de São Miguel (1634) and Forte de São Francisco do Penedo (1765-6). Of these, the Fortaleza de São Miguel is the best preserved.[2]

Luanda was Portugal's bridgehead from 1627, except during the Dutch rule of Luanda, from 1640 to 1648, as Fort Aardenburgh. The city served as the centre of slave trade to Brazil from circa 1550 to 1836.[3] The slave trade was conducted mostly with the Portuguese colony of Brazil; Brazilian ships were the most numerous in the port of Luanda. This slave trade also involved local merchants and warriors who profited from the trade.[4] During this period, no large scale territorial conquest was intended by the Portuguese; only a few minor settlements were established in the immediate hinterland of Luanda, some on the last stretch of the Kwanza River.

In the 17th century, the Imbangala became the main rivals of the Mbundu in supplying slaves to the Luanda market. In the 1750s, between 5,000 and 10,000 slaves were annually sold.[5] By this time, Angola, a Portuguese colony, was in fact like a colony of Brazil, paradoxically another Portuguese colony. A strong degree of Brazilian influence was noted in Luanda until the Independence of Brazil in 1822. In the 19th century, still under Portuguese rule, Luanda experienced a major economic revolution. The slave trade was abolished in 1836, and in 1844, Angola's ports were opened to foreign shipping. By 1850, Luanda was one of the greatest and most developed Portuguese cities in the vast Portuguese Empire outside Continental Portugal, full of trading companies, exporting (together with Benguela) palm and peanut oil, wax, copal, timber, ivory, cotton, coffee, and cocoa, among many other products. Maize, tobacco, dried meat, and cassava flour are also produced locally. The Angolan bourgeoisie was born by this time.

In 1889, Governor Brito Capelo opened the gates of an aqueduct which supplied the city with water, a formerly scarce resource, laying the foundation for major growth. Like most of Portuguese Angola, the cosmopolitan[6] city of Luanda was not affected by the Portuguese Colonial War (1961–1974); economic growth and development in the entire region reached record highs during this period. In 1972, a report called Luanda the "Paris of Africa". Throughout Portugal's Estado Novo period, Luanda grew from a town of 61,208 with 14.6% of those inhabitants being white in 1940, to a wealthy cosmopolitan major city of 475,328 in 1970 with 124,814 Europeans (26.3%) and around 50,000 mixed race inhabitants.[7][8] Luanda has also become one of the world's most expensive cities.[9]

Independence from Portugal

By the time of Angolan independence in 1975, Luanda was a modern city. The majority of its population was African, but it was dominated by a strong minority of white Portuguese origin. After the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon on April 25, 1974, with the advent of independence and the start of the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), most of the white Portuguese Luandans left as refugees,[10] principally for Portugal, with many travelling overland to South Africa. There was an immediate crisis, however, as the local African population lacked the skills and knowledge needed to run the city and maintain its well-developed infrastructure. The large numbers of skilled technicians among the force of Cuban soldiers sent in to support the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) government in the Angolan Civil War were able to make a valuable contribution to restoring and maintaining basic services in the city. In the following years, however, slums called musseques — which had existed for decades — began to grow out of proportion and stretched several kilometres beyond Luanda's former city limits as a result of the decades-long civil war, and because of the rise of deep social inequalities due to large-scale migration of civil war refugees from other Angolan regions. For decades, Luanda's facilities were not adequately expanded to handle this massive increase in the city's population. After 2002, with the end of the civil war and high economic growth rates fuelled by the wealth provided by the increasing oil and diamond production, major reconstruction started.[11]

Geography

Human geography

Luanda is divided into two parts, the Baixa de Luanda (lower Luanda, the old city) and the Cidade Alta (upper city or the new part). The Baixa de Luanda is situated next to the port, and has narrow streets and old colonial buildings.[12] However, massive new constructions have by now covered large areas beyond these traditional limits, and a number of previously independent nuclei — like Viana — were incorporated into the city.

Subdivisions

Since 2016, Luanda Province is divided into 9 municipalities:

- Belas

- Cacuaco

- Cazenga

- Icolo e Bengo

- Luanda

- Quiçama

- Kilamba Kiaxi

- Talatona

- Viana

A completely new satellite city, called Luanda Sul has been built. In Camama, Zango and Kilamba Kiaxi, more high-rise developments are to be built. The capital Luanda is growing constantly - and in addition, increasingly beyond the official city limits and even provincial boundaries.

Luanda is the seat of a Roman Catholic archbishop. It is also the location of most of Angola's educational institutions, including the private Catholic University of Angola and the public University of Agostinho Neto. It is also the home of the colonial Governor's Palace and the Estádio da Cidadela (the "Citadel Stadium"), Angola's main stadium, with a total seating capacity of 60,000.[13]

Luanda Sul

Luanda Sul is a satellite city of Luanda. A small stream flows in southern Luanda Sul, starting near the Quatro de Fevereiro Airport and emptying into the Atlantic Ocean.[14] Luanda International School is in Viana.[14]

Climate

Luanda has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSh). The climate is warm to hot but surprisingly dry, owing to the cool Benguela Current, which prevents moisture from easily condensing into rain. Frequent fog prevents temperatures from falling at night even during the completely dry months from June to October. Luanda has an annual rainfall of 405 millimetres (15.9 in), but the variability is among the highest in the world, with a co-efficient of variation above 40 percent.[15] Observed records since 1858 range from 55 millimetres (2.2 in) in 1958 to 851 millimetres (33.5 in) in 1916. The short rainy season in March and April depends on a northerly counter current bringing moisture to the city: it has been shown clearly that weakness in the Benguela current can increase rainfall about sixfold compared with years when that current is strong.[16]

| Climate data for Luanda (1961–1990, extremes 1879–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.9 (93) |

34.1 (93.4) |

37.2 (99) |

36.1 (97) |

36.1 (97) |

35.0 (95) |

28.9 (84) |

28.3 (82.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

36.1 (97) |

33.6 (92.5) |

37.2 (99) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.5 (85.1) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

28.8 (83.8) |

25.7 (78.3) |

23.9 (75) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.7 (81.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.7 (80.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.9 (75) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.2 (77.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.9 (75) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 18.0 (64.4) |

16.1 (61) |

20.0 (68) |

17.8 (64) |

17.8 (64) |

12.8 (55) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.2 (54) |

15.0 (59) |

17.8 (64) |

17.2 (63) |

17.8 (64) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 30 (1.18) |

36 (1.42) |

114 (4.49) |

136 (5.35) |

16 (0.63) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.04) |

2 (0.08) |

7 (0.28) |

32 (1.26) |

31 (1.22) |

405 (15.94) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 4 | 5 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 53 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80 | 78 | 80 | 83 | 83 | 82 | 83 | 85 | 84 | 81 | 82 | 81 | 82 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 217.0 | 203.4 | 207.7 | 192.0 | 229.4 | 207.0 | 167.4 | 148.8 | 150.0 | 167.4 | 186.0 | 201.5 | 2,277.6 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.0 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 6.2 |

| Source #1: Deutscher Wetterdienst[17] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[18] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

The inhabitants of Luanda are primarily members of African ethnic groups, mainly Ambundu, Ovimbundu, and Bakongo. The official and the most widely used language is Portuguese, although several Bantu languages are also used, chiefly Kimbundu, Umbundu, and Kikongo. There is a sizable minority population of European origin, especially Portuguese (about 260,000), as well as Brazilians and other Latin Americans. Over the last decades, a significant Chinese community has formed, as has a much smaller Vietnamese community. There is a sprinkling of immigrants from other African countries as well, including a small expatriate South African community. A small amount of people of Luanda are of mixed race — European/Portuguese and native African. In recent years, mainly since the mid-2000s, immigration from Portugal has increased due to Portugal's recession and poor economic situation.[19][20]

The population of Luanda has grown dramatically in recent years, due in large part to war-time migration to the city, which is safe compared to the rest of the country.[21] Luanda, however, in 2006 saw an increase in violent crime, particularly in the shanty towns that surround the colonial urban core.[22]

Economy

Around one-third of Angolans live in Luanda, 53% of whom live in poverty. Living conditions in Luanda are poor for most of the people, with essential services such as safe drinking water and electricity still in short supply, and severe shortcomings in traffic conditions.[23] On the other hand, luxury constructions for the benefit of the wealthy minority are booming. Luanda is one of the world's most expensive cities for resident foreigners.[24]

New import tariffs imposed in March 2014 made Luanda even more expensive. As an example, a half-litre tub of vanilla ice-cream at the supermarket was reported to cost US$31. The higher import tariffs applied to hundreds of items, from garlic to cars. The stated aim was to try to diversify the heavily oil-dependent economy and nurture farming and industry, sectors which have remained weak. These tariffs have caused much hardship in a country where the average salary was US$260 in 2010, the latest year for which data was available. However, the average salary in the booming oil industry was over 20 times higher at US$5,400.[25]

Manufacturing includes processed foods, beverages, textiles, cement and other building materials, plastic products, metalware, cigarettes, and shoes/clothes. Petroleum (found in nearby off-shore deposits) is refined in the city, although this facility was repeatedly damaged during the Angolan Civil War of 1975–2002. Luanda has an excellent natural harbour; the chief exports are coffee, cotton, sugar, diamonds, iron, and salt. The city also has a thriving building industry, an effect of the nationwide economic boom experienced since 2002, when political stability returned with the end of the civil war. Economic growth is largely supported by oil extraction activities, although massive diversification is taking place. Large investment (domestic and international), along with strong economic growth, has dramatically increased construction of all economic sectors in the city of Luanda.[26] In 2007, the first modern shopping mall in Angola was established in the city at Belas Shopping mall.[27]

Transport

Luanda is the starting point of the Luanda railway that goes due east to Malanje. The civil war left the railway non-functional, but the railway has been restored up to Dondo and Malanje.[28]

The main airport of Luanda is Quatro de Fevereiro Airport, which is the largest in the country. Currently, a new international airport, Angola International Airport is under construction southeast of the city, a few kilometres from Viana, which was expected to be opened in 2011.[29] However, as the Angolan government did not continue to make the payments due to the Chinese enterprise in charge of the construction, the firm suspended its work in 2010.

The port of Luanda serves as the largest port of Angola, and connects Angola to the rest of the world. Major expansion of this port is also taking place.[30] In 2014, a new port is being developed at Dande, about 30 km to the north.

Luanda's roads are in a poor state of repair, but are currently undergoing a massive reconstruction process by the government in order to relieve traffic congestion in the city. Major road repairs can be found taking place in nearly every neighbourhood, including a major 6-lane highway connected Luanda to Viana.[31]

Public transit is provided by the suburban services of the Luanda Railway, by the public company TCUL, and by a large fleet of privately owned collective taxis as white-blue painted minibuses called Candongueiro.

Candongueiros are usually Toyota Hiace vans, that are built to carry 12 people, although the candongueiros usually carry at least 15 people. They charge from 100 to 200 kwanzas per trip. They are known to disobey traffic rules, for example not stopping at signs and driving over pavements and aisles. Their stop points, known as "paragens" are often the places cause significant traffic because they often double park.

There is also a private bus company TURA working routes in Luanda.

Renewal and enlargement

The central government supposedly allocates funds to all regions of the country, but the capital region receives the bulk of these funds. Since the end of the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), stability has been widespread in the country, and major reconstruction has been going on since 2002 in those parts of the country that were damaged during the civil war. Luanda has been of major concern because its population had multiplied and had far outgrown the capacity of the city, especially because much of its infrastructure (water, electricity, roads etc.) had become obsolete and degraded.

Luanda has been undergoing major road reconstruction in the 21st century, and new highways are planned to improve connections to Cacuaco, Viana, Samba, and the new airport.[32]

Major social housing is also being constructed to house those who reside in slums, which dominate the landscape of Luanda. A large Chinese firm has been given a contract to construct the majority of replacement housing in Luanda.[33] The Angolan minister of health recently stated poverty in Angola will be overcome by an increase in jobs and the housing of every citizen.[34]

- Landscapes of Luanda

Luanda's reborn wealth has helped in the conservation of its historic sites, like the Fortress of São Miguel

Luanda's reborn wealth has helped in the conservation of its historic sites, like the Fortress of São Miguel The Porto de Luanda is Angola's largest, serving a growing city of over five million

The Porto de Luanda is Angola's largest, serving a growing city of over five million The Fortaleza de Sao Miguel (1576) watches over the south end of the bay at Luanda

The Fortaleza de Sao Miguel (1576) watches over the south end of the bay at Luanda The Cidade Alta in Luanda stretches along a ridge lined by pink colonial buildings

The Cidade Alta in Luanda stretches along a ridge lined by pink colonial buildings- Building under construction near Hotel Alvalade in Luanda

.jpg) The soaring Memorial Antonio Agostinho Neto

The soaring Memorial Antonio Agostinho Neto

Education

Universities:

International schools in Luanda:

- Escola Portuguesa de Luanda

- Colégio Português de Luanda

- Colégio S. Francisco de Assis

- Lycée Français de Luanda

- Luanda International School

- Escola- English School Community of Luanda Angola

Sports

In 2013 Luanda together with Namibe city, hosted the 2013 FIRS Men's Roller Hockey World Cup, the first time that a World Cup of roller hockey was held in Africa.

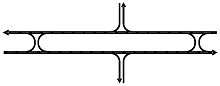

Roads

Luanda makes widespread use of an unusual variant of the median U-turn type intersection. This eliminates the need for traffic lights and encourages flee flow traffic on many main roads around the city. The intersection operates by not permitting the left turn at intersections. Angola drives on the right. A driver entering from a minor road wanting to turn left is required to join the main road traffic and proceed a u-turn and then backtrack in the opposite direction and then make a safe right turn.

The advantages:

- This arrangement converts a regular arterial road into a low cost Freeway with simple low cost at-grade interchanges.

- Collisions typically associated with at-grade intersections are eliminated. There is no crossing of on-coming traffic with this arrangement.

- Traffic lights are not required. No stopping or waiting at the intersection.

- A free flow of traffic is achieved.

- Reduced fuel consumption from vehicles not being required to accelerate away from a red light as well as reduced wear and tear on vehicles.

Disadvantages:

- Minor road traffic cannot directly cross the intersection. It has to join the main route and make a u-turn and return.

- Although traffic is flee flowing left turn traffic will encounter the inconvenience of additional travel distance sometimes as far as 2.5 km.

- The road surface has additional burden of longer travel distances, but has reduced wear at intersection and from braking.

- The u-turn is negotiated from the fast inner lane.

- Because of regular tight radius median u-turns the traffic speed is less than can be achieved on a regular freeway.

The Government of Angola takes a bold view of property rights and has been known to relocate property owners at short notice, Where the land is required to make space for the bulged u-turns.

It is unclear whether this intersection design has been in use prior or since the civil war.

The Luanda traffic is notoriously congested with gridlock and so arguably this intersection worsens the situation by lengthening the routes.

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Luanda is twinned with:

- São Paulo, Brazil[35][36]

- Salvador, Brazil[37]

- Houston, United States (2003)

- Lisbon, Portugal[38][39][40][41]

- Porto, Portugal[40][41]

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Windhoek, Namibia

- Bissau, Guinea-Bissau

- Brasilia, Brazil (since 1968)[6]

- Macau, China

- Maputo, Mozambique

- Tahoua, Niger

- Johannesburg, South Africa

- Cairo, Egypt

- Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

References

- ↑ "Luanda - Angola Today". Angola Today. Retrieved 2017-04-19.

- ↑ "Portuguese Colonial Remains". Colonialvoyage.com. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ↑ See Joseph Miller, Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, London & Madison/Wis, : James Currey & University of Wisconsin Press, 1988

- ↑ João C. Curto. Álcool e Escravos: O Comércio Luso-Brasileiro do Álcool em Mpinda, Luanda e Benguela durante o Tráfico Atlântico de Escravos (c. 1480-1830) e o Seu Impacto nas Sociedades da África Central Ocidental. Translated by Márcia Lameirinhas. Tempos e Espaços Africanos Series, vol. 3. Lisbon: Editora Vulgata. H-net.org. 2002. ISBN 978-972-8427-24-5.

- ↑ Njoku, Onwuka N. (1997). Mbundu. pp. 38–39.

- 1 2 "Mayor's International Council Sister Cities Program". Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. Archived from the original on 2007-12-23. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ↑ Angola antes da Guerra, a film of Luanda, Portuguese Angola (before 1975), youtube.com

- ↑ LuandaAnosOuro.wmv, a film of Luanda, Portuguese Angola (before 1975), youtube.com

- ↑ "Tokyo falls out of top 10 most expensive cities - FT.com". ft.com. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ↑ Flight from Angola, The Economist (August 16, 1975).

- ↑ The Economist: Marching towards riches and democracy? August 28, 2008

- ↑ MBRO%20de%202010.pdf Streets of Luanda from the Luanda Provincial Government website new pictures from Luanda City (Portuguese)

- ↑ "Estádio da Cidadela". zerozero.pt. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- 1 2 "Google Maps". maps.google.com. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ↑ Dewar, Robert E. and Wallis, James R; "Geographical patterning in interannual rainfall variability in the tropics and near tropics: An L-moments approach"; in Journal of Climate, 12; pp. 3457–3466

- ↑ Video from heavy rain falls in Luanda December 28, 2010

- ↑ "Klimatafel von Luanda, Prov. Luanda / Angola" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ "Station Luanda" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ "Tens of Thousands of Portuguese Emigrate to Fast-Growing Angola - SPIEGEL ONLINE". spiegel.de. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ↑ Smith, David (2012-09-16). "Portuguese escape austerity and find a new El Dorado in Angola". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "International Spotlight: Angola". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ↑ John Pike (2006-03-13). "ANGOLA: Easy access to guns concern as election nears". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ↑ Keeping the flow in Angola's slums Archived 2009-07-15 at the Wayback Machine., Department for International Development (DFID), United Kingdom (February 13, 2009)

- ↑ "Worldwide Cost of Living survey 2015 - City rankings". www.mercer.com. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ↑ "Angola's new import tariffs putting the squeeze on the poorest residents in one of the world's most expensive cities". The Independent. 2014-04-23. Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- ↑ "GDP growth: A look ahead". The Economist. 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "Belas shopping inaugurado em Luanda" (in Portuguese). Angonoticias.com. 28 March 2007. Retrieved 2015-05-26.

- ↑ "China International Fund Limited". Chinainternationalfund.com. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "China International Fund Limited". Chinainternationalfund.com. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ http://www.scottwilson.com/projects/transportation/maritime/luanda_oil_service_centre.aspx Scott Wilson projects] Archived March 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Angola: Part of Luanda's Highway Complete By December". allAfrica.com. 2008-08-15. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "OT Africa Line - Angola". Otal.com. 2004-07-01. Archived from the original on 2009-06-18.

- ↑ "China International Fund Limited". Chinainternationalfund.com. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "Angola Press - Economia - Pobreza será combatida com emprego e habitações sociais, diz ministro-adjunto do PM". Portalangop.co.ao. 2010-05-25. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "Pesquisa de Legislação Municipal - No 14471" [Research Municipal Legislation - No 14471]. Prefeitura da Cidade de São Paulo [Municipality of the City of São Paulo] (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2011-10-18. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- ↑ Lei Municipal de São Paulo 14471 de 2007 WikiSource (in Portuguese)

- ↑ Notícias, Varela (6 November 2012). "Prefeito João Henrique assina Termo de Irmanamento com a capital de Angola". Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- ↑ "Lisboa - Geminações de Cidades e Vilas" [Lisbon - Twinning of Cities and Towns]. Associação Nacional de Municípios Portugueses [National Association of Portuguese Municipalities] (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- ↑ "Acordos de Geminação, de Cooperação e/ou Amizade da Cidade de Lisboa" [Lisbon - Twinning Agreements, Cooperation and Friendship]. Camara Municipal de Lisboa (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- 1 2 "International Relations of the City of Porto" (PDF). © 2006–2009 Municipal Directorateofthe PresidencyServices InternationalRelationsOffice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- 1 2 Associação Porto Digital. "C.M. Porto". Cm-porto.pt. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

Bibliography

- See also: Bibliography of the history of Luanda

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People from Luanda. |

| Wikinews has related news: African Olympians and Paralympians prepare for their London odyssey |