Rusyns

|

Coat of Arms of Carpathian Ruthenia | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 75,000–85,000[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 33,482[1] | |

| 14,246[2] | |

| 10,183[note 1][3] | |

| 8,934 [note 2][4] | |

| 3,882[5] | |

| 2,879[6] | |

| 1,109[7] | |

| at 638–10,531 [note 3][8] | |

| at least 200 [note 4][9][10][11] | |

| Languages | |

| Rusyn · Ukrainian · Slovak · Serbian | |

| Religion | |

| Eastern Catholic Rite, Eastern Orthodoxy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

Ukrainians · Boykos Hutsuls · Lemkos | |

Rusyns, also known as Ruthenes (Rusyn: Русины Rusynÿ; also sometimes referred to as Руснакы Rusnakÿ – Rusnaks), are a primarily diasporic ethnic group who speak an East Slavic language known as Rusyn. The Rusyns descend from Ruthenian peoples who did not adopt the use of the ethnonym "Ukrainian" in the early 20th century. As residents of Carpathian Mountains region, Rusyns are also sometimes associated with Slovak highlander community of Gorals (literally - Highlanders).

The endonym Rusyn has frequently not been recognised by various governments and in other cases has been prohibited.[12]

The main population of Rusyns are Carpatho-Rusyns, Carpatho-Ruthenians, Carpatho-Russians of Carpathian Ruthenia: a discrete cross-border region of western Ukraine, north-east Slovakia, and south-east Poland. In official Ukrainian contexts, the various subgroups of Carpatho-Rusyns are often known collectively as Verkhovyntsi (Верховинці) literally meaning "Highlanders".

Today, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Serbia and Croatia officially recognize contemporary Rusyns (or Ruthenes) as an ethnic minority.[13] In 2007, Carpatho-Rusyns were recognized as a separate ethnicity in Ukraine by the Zakarpattia Regional Council, and in 2012 the Rusyn language gained official regional status in certain areas of the province as well as nationwide based on the 2012 Law of Ukraine "about principles of state policy in Ukraine". Most contemporary self-identified ethnic Rusyns live outside of Ukraine.

Of the estimated 1.2 million people of Rusyn origins,[12] as few as 90,000 individuals have been officially identified as such, in recent national censuses (see infobox above). This is due, in part, to the refusal of some governments to count Rusyns and/or allow them to self-identify on census forms, especially in Ukraine.[14] The ethnic classification of Rusyns as a separate East Slavic ethnicity distinct from Russians, Ukrainians, or Belarusians is, however, politically controversial.[15][16][17] The majority of Ukrainian scholars consider Rusyns to be an ethnic subgroup of the Ukrainian people.[18][19] This is disputed by some Lemko scholars [20] and the majority of Czech, Slovak, Canadian and American scholars. According to the 2001 Ukrainian Census about a third of Rusyns in Ukraine speak the Ukrainian language, while others stick to their native form.[21]

The terms "Rusyn," "Ruthenes," "Rusniak," "Lemak," "Lyshak" and "Lemko" are considered by some scholars to be historic, local and synonymical names for Carpathian Ukrainians; others hold that the terms "Lemko" and "Rusnak" are simply regional variations of "Rusyn" or "Ruthene."[12]

Location

Until the middle of the 19th century, ethnic Ukrainians referred to themselves as Ruthenians ("Rusyns" in Ukrainian, "Rutén" in Hungary). This term continues to be used today and is found in Ukrainian folk songs. The ethnonym Ukrainian came into widespread use only in modern times for political reasons, replacing the ethnonym Ruthenian initially in Sloboda Ukraine, then on the banks of the Dnieper River, and spreading to western Ukraine in the beginning of the 20th century. Today a minority group continues to use the ethnonym Rusyn for self-identification. These are primarily people living in the mountainous Transcarpathian region of western Ukraine and adjacent areas in Slovakia who use it to distinguish themselves from Ukrainians living in the central regions of Ukraine. Having eschewed the ethnonym Ukrainian, the Rusyns are asserting a local and separate Rusyn ethnic identity. Their distinctiveness as an ethnicity is, however, disputed.

Those Rusyns who self-identify today have traditionally come from or had ancestors who came from the Eastern Carpathian Mountain region. This region is often referred to as Carpathian Ruthenia. There are resettled Rusyn communities located in the Pannonian Plain, parts of present-day Serbia (particularly in Vojvodina – see also Ethnic groups of Vojvodina), as well as present-day Croatia (in the region of Slavonia). Rusyns also migrated and settled in Prnjavor, a town in the northern region of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. Analysis of population genetics shows statistical differences between Lemkos, Boykos, Hutzuls, and other Slavic or European populations.[22]

Many Rusyns emigrated to the United States and Canada. With the advent of modern communications such as the Internet, they are able to reconnect as a community. Concerns are being voiced regarding the preservation of their unique ethnic and cultural legacy.

History

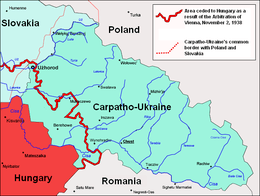

Rusyns formed two ephemeral states after World War I: the Lemko-Rusyn Republic and Komancza Republic. Prior to this time, some of the founders of the Lemko-Rusyn Republic were sentenced to death or imprisoned in Talerhof by the prosecuting attorney Kost Levytsky (Ukrainian: Кость Леви́цький), future president of the West Ukrainian National Republic.[23] In the interwar period, the Rusyn diaspora in Czechoslovakia enjoyed liberal conditions to develop their culture (in comparison with Ukrainians in Poland or Romania).[24] The Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine, which existed for one day on March 15, 1939, before it was occupied by Hungarian troops, is sometimes considered to have been a self-determining Rusyn state that had intentions to unite with Kiev. The Republic's president, Avgustyn Voloshyn, was an advocate of writing in Rusyn. Ukrainian insurgents from Galicia did attempt to bolster the defences of Carpatho-Ukraine but were unable to resist the Hungarian invaders, supported as the latter attacks were by Nazi Germany.

The Rusyns have always been subject to larger neighbouring powers, such as Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Slovakia, Poland, the Soviet Union, Ukraine, and Russia. In contrast to the modern Ukrainian national movement that united Western Ukrainians with those in the rest of Ukraine, the Rusyn national movement took two forms: one considered Rusyns a separate East Slavic nation, while the other was based on the concept of fraternal unity with Russians.

Most of the predecessors of the Eastern Slavic inhabitants of present-day Western Ukraine, as well as of Western Belarus, referred to themselves as Ruthenians (Rusyns) (Ukrainian: Русини, transliteration Rusyny) prior to the 19th century. Many of them became active participants in the creation of the Ukrainian nation and came to call themselves Ukrainians (Ukrainian: Українці, transliteration Ukrayintsi). There were, however, ethnic Rusyn enclaves, which were not a part of this movement: those living on the border of the same territory or in more isolated regions, such as the people from Carpathian Ruthenia, Poleshuks, or the Rusyns of Podlaskie. In the Soviet era, Boykos, Lemkos, Hutsuls, Rusyns, Ruski, Cossacks, Pinchuks, Polishchuks, and Lytvyns were classified as Ukrainian sub-groups.

Historically, the Polish and Hungarian states are considered to have contributed to the development of a Rusyn identity that is separate from that of traditional Ruthenians. Rusyns were recorded as a separate nationality by the censuses taken in pre-World War II Czechoslovakia and Hungary, In Poland, until 1939, 'Rusin' has been the official description of the whole nation, while "Ukrainians" were commonly the people involved in a nationalist movement. Nowadays all Polish citizens are allowed to define themselves by a single or double nationality,[25] i.e. "Lemko-Ukrainian", "Lemko-Polish", "Polish-Ukrainian", "Ukrainian-Polish" etc.

According to the 2001 Ukrainian census,[26] an overwhelming majority of Boykos, Lemkos, Hutsuls, Verkhovyntsi and Dolynians in Ukraine stated their nationality as Ukrainian. However, some of these ethnic groups consider themselves to be separate ethnicities, while others identify themselves as Rusyns. About 10,100 people, or 0.8%, of Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast (Province) identified themselves as Rusyns; by contrast, 1,010,000 considered themselves Ukrainians.[3] Research conducted by the University of Cambridge during the height of political Rusynism in the mid-1990s that focused on five specific regions within the Zakarpattia Oblast having the strongest pro-Rusyn cultural and political activism, found that only nine percent of the population of these areas claimed Rusyn ethnicity.[27][28] These numbers may change with the further acceptance of Rusyn identity and the Rusyn language in educational systems in the area; nevertheless in the present day, according to the Ukrainian census, most – over 99% – of the local inhabitants consider themselves to be Ukrainians.[3]

The Rusyn national movement is much stronger among those Rusyn groups that became geographically separated from present-day Ukrainian territories, for example the Rusyn emigrants in the United States and Canada, as well as the Rusyns living within the borders of Slovakia. The 2001 census in Slovakia showed that 24,000 people considered themselves ethnically Rusyn while 11,000 considered themselves to be ethnically Ukrainian.[29] The Pannonian Rusyns in Serbia, who migrated there during the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, also consider themselves to be Rusyns. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, some Rusyns resettled in Vojvodina (in present-day Serbia), as well as in Slavonia (in present-day Croatia). Still other Rusyns migrated to the northern regions of present Bosnia and Herzegovina. Until the 1971 Yugoslav census, both Ukrainians (Serbian Cyrillic: Украјинци, tr. Ukrajinci) and Rusyns (Serbian Cyrillic: Русини, tr. Rusini) in these areas were recorded collectively as "Ruthenes". Podkarpatskije Rusiny is considered the Rusyn "national anthem".

Since 1992, the Zakarpattia regional council has twice appealed for recognition of Rusyns as a distinct nationality twice to the Ukrainian parliament (Verkhovna Rada). According to the 2001 All-Ukrainian Census, approximately 10,000 self-identified Rusyns reside within Zakarpattia Oblast alone. In August 2006, the UN Committee on liquidation on racial discrimination urged the Government of Ukraine to recognize Rusyns as a national minority. This is recognized in 22 countries around the globe. In March 2007, the Zakarpattia Regional Council adopted a decision which recognized Rusyns as a separate national minority at the oblast level.[13] By the same decision the Zakarpattia Regional Council petitioned the Ukrainian central authorities to recognize Rusyns as an ethnic minority at the state level.

Autonomist and separatist movements

A considerable controversy has arisen regarding the Rusyn separatist movement led by the Orthodox priest Dmitri Sidor (now Archbishop of Uzhorod, in the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate)), his relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church and funding for his activities.[30][31] Russia has, as a result of the Russian census of 2002, recognized the Rusyns as a separate ethnic group in 2004, and has been accused of fueling ethnic tensions and separatism among Rusyns.[32]

A criminal case under Part 2, Art. 110 of the Ukrainian Criminal Code was initiated after the 1st European Congress of Rusyns took place in Mukachevo on June 7, 2008. At that particular congress it was recognized the reinstating of the Zakarpattia's special status as special "territory of Rusyns to the south of the Carpathians" with self-government under the constitutional name Subcarpathian Rus. On October 29, in Mukachevo at a 2nd Congress, a memorandum was signed calling for the authorities to recognise the Subcarpathian Rus autonomy (by December 1). That same day, according to the Kommersant-Ukraine (Ukrainian edition) agents of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) questioned Dmytro Sidor and Yevgeniy Zhupan.[33] They were summoned to SBU as witnesses in a criminal case "on the infringement on territorial integrity of Ukraine" initiated in June 2008. However the investigators were interested in the circumstances and sources of financing the 2nd European Congress of Rusyns that took place on October 25, at which the memorandum on reinstating Rusyn statehood was signed. According to Dmytro Sidor the Rusyn movement is financed through business. At the same time Rusyn leaders claim that it does not infringe on territorial integrity of the country. Sydor was reportedly convicted on charges relating to separatism in 2012.

Population genetics

The few studies made thus far of the genetics of Rusyns indicate a common ancestry with other modern Europeans.[34] An analysis of maternal lineages found that Rusyns have the highest frequency of Haplogroup H1 (mtDNA) found to that date. Haplogroup M* also reaches its regional peak among Rusyns.[35] Analysis of population genetics shows statistical differences between Rusyns and other Slavic or European populations.[35]

Religion

In 1994, the historian Paul Robert Magocsi stated that there were approximately 690,000 Carpatho-Rusyn church members in the United States, with 320,000 belonging to the largest Byzantine Rite Catholic affiliations, 270,000 to the largest Eastern Orthodox affiliations, and 100,000 to various Protestant and other denominations.[36]

Byzantine Catholics

Most Rusyns are Eastern Catholics of the Byzantine Rite, who since the Union of Brest in 1596 and the Union of Uzhhorod in 1646 have been in communion with the See of Rome. They have their own particular Church, the Ruthenian Catholic Church, distinct from the Latin Rite Catholic Church. It has retained the Byzantine Rite liturgy, sometimes including the Old Slavonic Church language, and the liturgical forms of Byzantine or Eastern Orthodox Christianity.

The Pannonian Rusyns of the Croatia are organized under the Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Križevci, and those in the region of Vojvodina (northern Serbia), are organized under the Byzantine Catholic Apostolic Exarchate of Serbia. Those in the diaspora in the United States established the Byzantine Catholic Metropolitan Church of Pittsburgh.

Eastern Orthodox

Although originally associated with the Eastern Orthodox Eparchy of Mukachevo, under the Metropolitanate of Kiev, that diocese was suppressed after the Union of Uzhhorod. New Eastern Orthodox Eparchy of Mukachevo and Prešov was created in 1931 under the auspices of the Serbian Orthodox Church. That eparchy was divided in 1945, eastern part joining Russian Orthodox Church as the Eparchy of Mukachevo and Uzhhorod, while western part was reorganized as Eastern Orthodox Eparchy of Prešov of the Czech and Slovak Orthodox Church. The affiliation of Eastern Orthodox Rusyns was adversely affected by the Communist revolution in the Russian Empire and the subsequent Iron Curtain which split the Orthodox diaspora from the Eastern Orthodox believers living in the ancestral homelands. A number of émigré communities have claimed to continue the Orthodox Tradition of the pre-revolution church while either denying or minimizing the validity of the church organization operating under Communist authority. For example, the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) was granted autocephalous (self-governing) status by the Moscow Patriarchate in 1970. Although approximately 25% of the OCA was Rusyn (referred to as "Ruthenian") in the early 1980s, an influx of Eastern Orthodox émigrés from other nations and new converts wanting to connect with the Eastern Church have lessened the impact of a particular Rusyn emphasis in favor of a new American Orthodoxy.

Many Rusyn Americans left Catholicism for Eastern Orthodoxy in 19th century due to disputes with the Latin rite bishops, who viewed different practices in the Byzantine rite (such as married clergy) with suspicion. After a bitter fight with Archbishop John Ireland, Father Alexis Toth, himself a Rusyn from Hungary, converted to Eastern Orthodoxy and eventually led as many as 20,000 Rusyn-Americans from Catholicism into Eastern Orthodoxy, for which he was canonized by the Orthodox Church.

Another large segment of Rusyn Americans belong to the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese, which is headquartered in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. From its early days, this group was recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate as a self-governing diocese.

Ethnic subgroups

Carpatho-Rusyns

- Subcarpathian Rusyns

- Dolynians

- Verkhovynians, descendants of Boykos which moved in the 17th and 18th centuries from Galicia to the highland region of Subcarpathian Rus called Verkhovyna. Verkhovynians currently inhabit the eastern part of Velykyy Bereznyi Raion, Volovets Raion and the northern and western parts of Mizhhiria Raion.

- Prešov Rusyns

- Sotaks, Zemplín Rusyns which live in the present-day Slovak districts of Snina, Michalovce, Humenné and Sobrance.

- Tsopaks, Spiš Rusyns, which use word "цо/tso" within the meaning of "what." Tsopaks earned their name through their frequent use of the phrase "Цо пак?/Tso pak?" ("What then?").

- Kraynyaks

- Galician Rusyns

- Bukovinian Rusyns

Pannonian Rusyns

Pannonian Rusyn language has been granted official status and was codified in Serbia's province of Vojvodina. Since 1995, it has also been recognized and codified as a minority language in Slovakia (in those areas comprising at least 20% Rusyns). The Rusyn language in Vojvodina, however, shares many similarities with Slovak, and is sometimes considered a separate language, sometimes a dialect of Slovak.

Hutsuls

Hutsuls are a special ethnic group. Many Hutsuls now identify as Ukrainians. Before the 14th or 15th centuries Hutsuls lived in Podolia. Then they migrated from Podolia to Galicia and Bukovina. In the 15th or 16th centuries Hutsuls migrated to the east of Subcarpathian Rus.

Gallery

See also

- Rusyn Americans

- Ruthenians

- Rus' people

- Carpatho-Rusyn Society

- Carpathian Wooden Churches

- Red Ruthenia

- Pannonian Rusyns

- Eparchy of Mukačevo and Prešov

- St. Nicholas Byzantine Catholic Church

Notes

- ↑ The total figure is merely an estimation; sum of all the referenced populations below.

- ↑ A minimum estimate; there is no option to identify as Rusyn in Ukrainian censuses. The figure is a minimum estimate based on the proportions of locally-born ethnic "Ukrainians" officially resident in relevant West Ukrainian oblasts; the Dolinyan, Boyko and Hutsul areas are also included.

- ↑ Respondents in the U.S. census identified as Carpatho Rusyn

- ↑ According to the 2011 Polish census, 10,531 respondents identified as Lemkos, separately from Rusyns.

- ↑ While an estimated 200 people identified themselves as "Rusyns" in 2011, in the 2002 Romanian census, 3,890 people identified as Hutsuls (Romanian: Huțuli; Rusyn Hutsuly) – a minority whose members often identifiy or are regarded as a subgroup of the Rusyns. A further 61,091 Romanian citizens identified as Ukrainian (Romanian: Ucraineni). As the archaic exonym "Ruthenians" was applied indiscriminately to both Rusyns and Ukrainians, some Ukrainian-Romanians may also regard themselves as Rusyns in the sense of a subgroup of a broader Ukrainian identity.

References

- ↑ "Permanently resident population by nationality and by regions and districts" (PDF) (in Slovak). Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-17.

- ↑ Становништво према националној припадности [Population by ethnicity]. Serbian Republic Institute of Statistics (in Serbian).

- 1 2 3 Чисельність осіб окремих етнографічних груп украінського етносу та їх рідна мова [Number of persons individual ethnographic groups of the Ukrainian ethnicity and their native language]. ukrcensus.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). 2001. Retrieved 4 March 2016. Карта говорiв украïнськоï мови, 10.10.2008; Энциклопедический словарь: В 86 томах с иллюстрациями и дополнительными материалами. Edited by Андреевский, И.Е. − Арсеньев, К.К. − Петрушевский, Ф.Ф. − Шевяков, В.Т., s.v. Русины. Online version. Вологда, Russia: Вологодская областная универсальная научная библиотека, 2001 (1890−1907), 10.10.2008; Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Edited by Gordon, Raymond G., Jr., s.v. Rusyn. Fifteenth edition. Online version. Dallas, Texas, U.S.A.: SIL International, 2008 (2005), 10.10.2008; Eurominority: Peoples in search of freedom. Edited by Bodlore-Penlaez, Mikael, s.v. Ruthenians. Quimper, France: Organization for the European Minorities, 1999–2008, 10.10.2008.

- ↑ "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported, 2010 American Community Survey, 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- ↑ Population by nationality, mother tongue, language spoken with family members or friends and affinity with nationalities’ cultural values - official 2011 census data

- ↑ "STANOVNIŠTVO PREMA NARODNOSTI, PO GRADOVIMA/OPĆINAMA, POPIS 2001" [Population by ethnicity in cities and municipalities, 2001 Census] (in Croatian). State Institute for Statistics of the Republic of Croatia.

- ↑ "Rusínská národnostní menšina". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Ludność. Stan i struktura demograficzno społeczna" [State and structure of the social demographics of the population] (PDF). Central Statistical Office of Poland (in Polish). 2013. p. 91. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Moser, Michael (2016). ""Rusyn"". In Tomasz Kamusella, Motoki Nomachi & Catherine Gibson. The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders. Basingstoke UK: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 132.

- ↑ "Populaţia după etnie" (PDF) (in Romanian). Institutul Naţional de Statistică. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ↑ "Date naţionale" (in Romanian). Erdélyi Magyar Adatbank. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- 1 2 3 Paul Magocsi (1995). "The Rusyn Question". Political Thought. 2–3 (6).

- 1 2 Ukraine’s ethnic minority seeks independence. RT

- ↑ "Законодавство України не дозволяє визнати русинів Закарпаття окремою національністю". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Professor Ivan Pop: Encyclopedia of Subcarpathian Ruthenia(Encyclopedija Podkarpatskoj Rusi). Uzhhorod, 2000. With support from Carpatho-Russian ethnic research center in the USA ISBN 9667838234

- ↑ Paul Robert Magocsi, Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture . University of Toronto Press, June 2002. ISBN 978-0-8020-3566-0

- ↑ Tom Trier (1998), Inter-Ethnic Relations in Transcarpathian Ukraine

- ↑ Wilson, Andrew (2000), The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation, New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08355-6.

- ↑ Taras Kuzio (2005), "The Rusyn Question in Ukraine: Sorting Out Fact from Fiction", Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism, XXXII

- ↑ Trochanowski, Piotr (14 January 1992). "Lemkowszczyzna przebudzona" [Lemkivshchyna Awakened]. Gazeta Wyborcza (Krakowski dodatek) (in Polish). Cracow. p. 2.

- ↑ "Number of persons of individual ethnic groups other than those of Ukrainian ethnicity and their native language" Чисельність осіб окремих етнографічних груп украінського етносу та їх рідна мова [Number of persons of individual ethnic groups other than those of Ukrainian ethnicity and their native language] (in Ukrainian). State Committee for Statistics of Ukraine: 2001 Census. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Nikitin, AG; Kochkin IT, June CM, Willis CM, McBain I, Videiko MY (2008). "Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in Boyko, Hutsul and Lemko populations of Carpathian highlands". Human Biology. 81 (1): 43–58. ISSN 0018-7143. OCLC 432539982. PMID 19589018. doi:10.3378/027.081.0104.

Lemkos shared the highest frequency of haplogroup I ever reported and the highest frequency of haplogroup M* in the region. MtDNA haplogroup frequencies in Boykos were different from most modern European populations.

- ↑ Vavrik, Vasilij Romanowicz (2001). Terezin i Talergof : k 50-letnej godovščine tragedii galic.-rus. naroda (in Russian). Moscow: Soft-izdat. OCLC 163170799. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ Orest Subtelny, Ukraine. A History. Second edition, 1994. p. 350-351. Subtelny treats transcarpathian Rusyns as a group of Ukrainians

- ↑ Ludność. Stan i struktura demograficzno-społeczna. Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011

- ↑ "Ukrainian National Census 2001" Всеукраїнського перепису населення 2001 [Ukrainian National Census 2001] (in Ukrainian). ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Taras Kuzio (2005). The Rusyn Question in Ukraine: Sorting Out Fact from Fiction. Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism, XXXII

- ↑ Political and Ethno-Cultural Aspects of the Rusyns’ problem: A Ukrainian Perspective - by Natalya Belitser, Pylyp Orlyk Institute for Democracy, Kyiv, Ukraine

- ↑ Peter Nagy. "Slovakia census 2001 - Genealogy". centroconsult.sk. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ↑ Дмитрий Сидор отказался давать показания СБУ и "наехал" на журналистов [Dmitry Sidorov refused to give evidence to a Ukrainian Security Services investigation and "struck back" at journalists]. ua-reporter.com (in Russian). 19 November 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ ПОЛІТИЧНЕ РУСИНСТВО І ЙОГО СПОНСОРИ [Political Rusynism and its sponsors]. ua-reporter.com (in Ukrainian). 11 July 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ↑ Україна в лещатах російських спецслужб [Ukraine is in the grip of Russian secret services]. radiosvoboda.org (in Ukrainian). 25 December 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Лідерів русинів допитали в СБУ [Leaders of Rusyns were questioned at the SBU]. ua.glavred.info (in Ukrainian). 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011.

- ↑ Willis, Catherine (2006). "Study of the Human Mitochondrial DNA Polymorphism". McNair Scholars Journal. 10 (1). Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- 1 2 Nikitin, Alexey G.; Kochkin, Igor T.; June, Cynthia M.; Willis, Catherine M.; Mcbain, Ian; Videiko, Mykhailo Y. (2009). "Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in Boyko, Hutsul and Lemko populations of Carpathian highlands". Human Biology. Human Biology (The International Journal of Population Biology and Genetics). 81 (1): 43–58. PMID 19589018. doi:10.3378/027.081.0104. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Magocsi, Paul R (1994). Our People: Carpatho-Rusyns and Their Descendants in North America. Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario. ISBN 9780919045668. OCLC 30973382.

Further reading

- Chlebowski, Cezary (1983). Wachlarz: Writings on the Liberating Organization, a Division of the National Army (Wachlarz: Monografia wydzielonej organizacji dywersyjnej Armii Krajowej : wrzesien 1941-marzec 1943), Instytut Wydawniczy Pax. ISBN 83-211-0419-3.

- Dyrud, Keith P. (1992). The Quest for the Rusyn Soul: The Politics of Religion and Culture in Eastern Europe and in America, 1890-World War I, Balch Institute Press. ISBN 0-944190-10-3.

- Patricia Krafeik, ed. (1994). The Rusyns, Eastern European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-190-9.

- Lansdowne, Alan (2008), Is there a credible case for Rusyn National Self-Determination in Ukraine?, School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies MA Thesis

- Mayer, Maria, translated by Janos Boris (1998). Rusyns of Hungary: Political and Social Developments, 1860-1910, Eastern European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-387-1.

- Petrov, Aleksei (1998). Medieval Carpathian Rus': The Oldest Documentation about the Carpatho-Rusyn Church and Eparchy, Eastern European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-388-X.

- Rusinko, Elaine (2003). Straddling Borders: Literature and Identity in Subcarpathian Rus', University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3711-9.

- 1978 Shaping of a National Identity: Subcarpathian Rus', 1848-1948, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-80579-8.

- 1988 Carpatho-Rusyn Studies: An Annotated Bibliography (V. 1: Garland Reference Library of the Humanities), Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-1214-3.

- 1994 Our People: Carpatho-Rusyns and Their Descendants in North America, Society of Multicultural Historical. ISBN 0-919045-66-9.

- 1994 The Rusyns of Slovakia, East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-278-6.

- 1996 A New Slavic Nation is Born, East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-331-6.

- 1999 Carpatho-Rusyn Studies: An Annotated Bibliography, 1985-1994, Vol. 2, Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-88033-420-7.

- 2000 Of the Making of Nationalities There Is No End, East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-438-X.

- 2000, with Sandra Stotsky and Reed Ueda, The Carpatho-Rusyn Americans (Immigrant Experience), Chelsea House Publications. ISBN 0-7910-6284-8.

- 2002 Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture, University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3566-3.

- 2006 Carpatho-Rusyn Studies : An Annotated Bibliography Vol.3 1995-1999, East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-531-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rusyns. |

- The Carpathian Connection

- The Carpatho-Rusyn Society

- Carpatho Rusyn Knowledge Base

- American Carpatho-Russian Diocese

_..jpg)

_and_Przemy%C5%9Bl_area_Ukrainians_in_original_goral_folk-costumes..jpg)