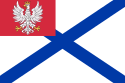

Congress Poland

| Kingdom of Poland | ||||||||||

| Królestwo Polskie (in Polish) Царство Польское (in Russian) Tsarstvo Polskoye | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Motto Z nami Bóg! "God is with us!" | ||||||||||

| Anthem Pieśń narodowa za pomyślność króla "National Song to the King's Well-being" | ||||||||||

Map of Congress Poland, circa 1815, following the Congress of Vienna. The Russian Empire is shown in light green. | ||||||||||

| Capital | Warsaw | |||||||||

| Languages | Polish, Russian | |||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | |||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | |||||||||

| King | ||||||||||

| • | 1815–1825 | Alexander I | ||||||||

| • | 1825–1855 | Nicholas I | ||||||||

| • | 1855–1881 | Alexander II | ||||||||

| • | 1881–1894 | Alexander III | ||||||||

| • | 1894–1915 | Nicholas II | ||||||||

| Namiestnik-Viceroy | ||||||||||

| • | 1815–1826 | Józef Zajączek (first) | ||||||||

| • | 1914–1915 | Pavel Yengalychev (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Sejm | |||||||||

| • | Upper house | Senate | ||||||||

| • | Lower house | Chamber of Deputies | ||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| • | Established | 9 June 1815 | ||||||||

| • | Constitution adopted | 27 November 1815 | ||||||||

| • | November Uprising | 29 November 1830 | ||||||||

| • | January Uprising | 23 January 1863 | ||||||||

| • | Collapsed | 1867 or 1915[a] | ||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||

| • | 1815 | 128,500 km2 (49,600 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||

| • | 1815 est. | 3,200,000 | ||||||||

| Density | 25/km2 (64/sq mi) | |||||||||

| • | 1897 est. | 9,402,253 | ||||||||

| Currency |

| |||||||||

| ||||||||||

The Kingdom of Poland,[1] informally known as Congress Poland[2] or Russian Poland, was created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a sovereign state of the Russian part of Poland connected by personal union with the Russian Empire under the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland until 1832. Then, it was gradually politically integrated into Russia over the course of the 19th century, made an official part of the Russian Empire in 1867, and finally replaced during the Great War by the Central Powers in 1915 with the nominal Regency Kingdom of Poland.[a]

Though officially the Kingdom of Poland was a state with considerable political autonomy guaranteed by a liberal constitution, its rulers, the Russian Emperors, generally disregarded any restrictions on their power. Thus effectively it was little more than a puppet state of the Russian Empire.[3][4] The autonomy was severely curtailed following uprisings in 1830–31 and 1863, as the country became governed by namiestniks, and later divided into guberniya (provinces).[3][4] Thus from the start, Polish autonomy remained little more than fiction.[5]

The territory of the Kingdom of Poland roughly corresponds to the Kalisz Region and the Lublin, Łódź, Masovian, Podlaskie and Świętokrzyskie Voivodeships of Poland, southwestern Lithuania and part of Grodno District of Belarus.

Naming

Although the official name of the state was the Kingdom of Poland, in order to distinguish it from other Kingdoms of Poland, it was sometimes referred to as "Congress Poland".

History

The Kingdom of Poland was created out of the Duchy of Warsaw, a French client state, at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 when the great powers reorganized Europe following the Napoleonic wars. The creation of the Kingdom created a partition of Polish lands in which the state was divided among Russia, Austria and Prussia.[6] The Congress was important enough in the creation of the state to cause the new country to be named for it.[7][8] The Kingdom lost its status as a sovereign state in 1831 and the administrative divisions were reorganized. It was sufficiently distinct that its name remained in official Russian use, although in the later years of Russian rule it was replaced [9] with the Privislinsky Krai (Russian: Привислинский Край). Following the defeat of the November Uprising its separate institutions and administrative arrangements were abolished as part of increased Russification to be more closely integrated with the Russian Empire. However, even after this formalized annexation, the territory retained some degree of distinctiveness and continued to be referred to informally as Congress Poland until the Russian rule there ended as a result of the advance by the armies of the Central Powers in 1915 during World War I.

Originally, the Kingdom had an area of roughly 128,500 km2 and a population of approximately 3.3 million. The new state would be one of the smallest Polish states ever, smaller than the preceding Duchy of Warsaw and much smaller than the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which had a population of 10 million and an area of 1 million km2.[8] Its population reached 6.1 million by 1870 and 10 million by 1900. Most of the ethnic Poles in the Russian Empire lived in the Congress Kingdom, although some areas outside it also contained a Polish majority.

The Kingdom of Poland largely re-emerged as a result of the efforts of Adam Jerzy Czartoryski,[10] a Pole who aimed to resurrect the Polish state in alliance with Russia. The Kingdom of Poland was one of the few contemporary constitutional monarchies in Europe, with the Emperor of Russia serving as the Polish King. His title as chief of Poland in Russian, was Tsar, similar to usage in the fully integrated states within the Empire (Georgia, Kazan, Siberia).

Initial independence

Theoretically the Polish Kingdom in its 1815 form was a semi-autonomous state in personal union with Russia through the rule of the Russian Emperor. The state possessed the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland, one of the most liberal in 19th century Europe,[10] a Sejm (parliament) responsible to the King capable of voting laws, an independent army, currency, budget, penal code and a customs boundary separating it from the rest of Russian lands. Poland also had democratic traditions (Golden Liberty) and the Polish nobility deeply valued personal freedom. In reality, the Kings had absolute power and the formal title of Autocrat, and wanted no restrictions on their rule. All opposition to the Emperor of Russia was suppressed and the law was disregarded at will by Russian officials.[11] Though the absolute rule demanded by Russia was difficult to establish due to Poland's liberal traditions and institutions, the independence of the Kingdom lasted only 15 years; initially Alexander I used the title of the King of Poland and was obligated to observe resolutions of the constitution. However, in time the situation changed and he granted the viceroy, Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich, almost dictatorial powers.[7] Very soon after Congress of Vienna resolutions were signed, Russia ceased to respect them. In 1819, Alexander I abolished freedom of the press and introduced preventory censorship. Resistance to Russian control began in the 1820s.[5] Russian secret police commanded by Nikolay Nikolayevich Novosiltsev started persecution of Polish secret organizations and in 1821 the King ordered the abolition of Freemasonry, which represented Poland's patriotic traditions.[5] Beginning in 1825, the sessions of the Sejm were held in secret.

Uprisings and loss of autonomy

Alexander I's successor, Nicholas I was crowned King of Poland on 24 May 1829 in Warsaw, but he declined to swear to abide by the Constitution and continued to limit the independence of the Polish kingdom. Nicholas' rule promoted the idea of Official Nationality, consisting of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality. In relation to Poles, those ideas meant assimilation: turning them into loyal Orthodox Russians.[5] The principle of Orthodoxy was the result of the special role it played in Russian Empire, as the Church was in fact becoming a department of state,[5] and other religions discriminated against; for instance, Papal bulls could not be read in the Kingdom of Poland without agreement from the Russian government.

The rule of Nicholas also meant end of political traditions in Poland; democratic institutions were removed, an appointed—rather than elected—centralized administration was put in place, and efforts were made to change the relations between the state and the individual. All of this led to discontent and resistance among the Polish population.[5] In January 1831, the Sejm deposed Nicholas I as King of Poland in response to his repeated curtailing of its constitutional rights. Nicholas reacted by sending Russian troops into Poland, resulting in the November Uprising.[12]

Following an 11-month military campaign, the Kingdom of Poland lost its semi-independence and was integrated much more closely with the Russian Empire. This was formalized through the issuing of the Organic Statute of the Kingdom of Poland by the Emperor in 1832, which abolished the constitution, army and legislative assembly. Over the next 30 years a series of measures bound Congress Poland ever more closely to Russia. In 1863 the January Uprising broke out, but lasted only two years before being crushed. As a direct result, any remaining separate status of the kingdom was removed and the political entity was directly incorporated into the Russian Empire. The unofficial name Privislinsky Krai (Russian: Привислинский Край), i.e., 'Vistula Land', replaced 'Kingdom of Poland' as the area's official name and the area became a namestnichestvo under the control of a namiestnik until 1875, when it became a Guberniya.

Government

The government of Congress Poland was outlined in the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland in 1815. The Emperor of Russia was the official head of state, considered the King of Poland, with the local government headed by the Viceroy of the Kingdom of Poland (Polish: Namiestnik), Council of State and Administrative Council, in addition to the Sejm.

In theory, Congress Poland possessed one of the most liberal governments of the time in Europe,[10] but in practice the area was a puppet state of the Russian Empire. The liberal provisions of the constitution, and the scope of the autonomy, were often disregarded by the Russian officials.[8][10][11]

Executive leadership

The office of "Namiestnik" was introduced in Poland by the 1815 constitution of Congress Poland. The Viceroy was chosen by the King from among the noble citizens of the Russian Empire or the Kingdom of Poland. The Viceroy supervised the entire public administration and, in the monarch's absence, chaired the Council of State, as well as the Administrative Council. He could veto the councils' decisions; other than that, his decisions had to be countersigned by the appropriate government minister. The Viceroy exercised broad powers and could nominate candidates for most senior government posts (ministers, senators, judges of the High Tribunal, councilors of state, referendaries, bishops, and archbishops). He had no competence in the realms of finances and foreign policy; his military competence varied.

The office of "namiestnik" or Viceroy was never abolished; however, after the January 1863 Uprising it disappeared. The last namiestnik was Friedrich Wilhelm Rembert von Berg, who served from 1863 to his death in 1874. No namiestnik was named to replace him;[13] however, the role of namestnik—viceroy of the former kingdom passed to the Governor-General of Warsaw[14]—or, to be more specific, of the Warsaw Military District (Polish: Warszawski Okręg Wojskowy, Russian: Варшавский Военный Округ).

The governor-general answered directly to the Emperor and exercised much broader powers than had the namiestnik. In particular, he controlled all the military forces in the region and oversaw the judicial systems (he could impose death sentences without trial). He could also issue "declarations with the force of law," which could alter existing laws.

Administrative Council

The Administrative Council (Polish: Rada Administracyjna) was a part of Council of State of the Kingdom. Introduced by the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland in 1815, it was composed of 5 ministers, special nominees of the King and the Viceroy of the Kingdom of Poland. The Council executed the King's will and ruled in the cases outside the ministers competence and prepared projects for the Council of State.

Administrative divisions

The administrative divisions of the Kingdom changed several times over its history, and various smaller reforms were also carried out which either changed the smaller administrative units or merged/split various subdivisions.

Immediately after its creation in 1815, the Kingdom of Poland was divided into departments, a relic from the times of the French-dominated Duchy of Warsaw.

On 16 January 1816 the administrative division was reformed, with the departments being replaced with more traditionally Polish voivodeships (of which there were eight), obwóds and powiats. On 7 March 1837, in the aftermath of the November Uprising earlier that decade, the administrative division was reformed again, bringing Congress Poland closer to the structure of the Russian Empire, with the introduction of guberniyas (governorate, Polish spelling gubernia). In 1842 the powiats were renamed okręgs, and the obwóds were renamed powiats. In 1844 several governorates were merged with others, and some others renamed; five governorates remained.

In 1867, following the failure of the January Uprising, further reforms were instituted which were designed to bring the administrative structure of Poland (now de facto the Vistulan Country) closer to that of the Russian Empire. It divided larger governorates into smaller ones, introduced the gmina (a new lower level entity), and restructured the existing five governorates into 10. The 1912 reform created a new governorate – Kholm Governorate – from parts of the Sedlets and Lublin Governorates. It was split off from the Vistulan Country and made part of the Southwestern Krai of the Russian Empire.[15]

Economy

Despite the fact that the economic situation varied at times, Congress Poland was one of the largest economies in the world.[16] In the mid 1800s the region became heavily industrialized,[17] however, agriculture still maintained a major role in the economy.[18] In addition, the export of wheat, rye and other crops was significant in stabilizing the financial output.[18] An important trade partner of Congress Poland and the Russian Empire was Great Britain, which imported goods in large amounts.

Since agriculture was equivalent to 70% of the national income, the most important economic transformations included the establishment of mines and the textile industry; the development of these sectors brought more profit and higher tax revenues. The beginnings were difficult due to floods and intense diplomatic relationship with Prussia. It was not until 1822 when Prince Francis Xavier Drucki-Lubecki negotiated to open the Polish market to the world.[19] He also tried to introduce appropriate protective duties. A large and profitable investment was the construction of the Augustów Canal connecting Narew and Neman Rivers, which allowed to bypass Danzig (Gdańsk) and high Prussian tariffs.[20] Drucki-Lubecki also founded the Bank of Poland, for which he is mostly remembered.[19]

The first Polish steam mill was built in 1828 in Warsaw-Solec; the first textile machine was installed in 1829.[17] Greater use of machines led to production in the form of workshops. The government was also encouraging foreign specialists, mostly Germans, to upkeep larger establishments, or to undertake production.[17] The Germans were also relieved of tax burden.[21] This allowed to create one of the largest European textile centres in Łódź and in surrounding towns like Ozorków and Zduńska Wola.[22] These small and initially insignificant settlements later developed into large and multicultural cities, where Germans and Jews were the majority in the population. With the abolition of border customs in 1851 and further economic growth, Polish cities were gaining wealth and importance. Most notably, Warsaw, being associated with the construction of railway lines and bridges, gained priority in the entire Russian market.

Although the economic and industrial progress occurred rapidly, most of the farms, called folwarks, chose to rely on serfs and paid workforce. Only a few have experimented by obtaining proper machinery and plowing equipment from England.[17] New crops were being cultivated like sugar beet, which marked the beginning of Polish sugar refineries. The use of iron cutters and plows was also favoured among the farmers. During the January Uprising the occupying authorities sought to deprive peasant insurgents of their popularity among landed gentry.[17] Taxes were raised and the overall economic situation of commoners worsened. The noblemen and landowners were, on the other hand, provided with more privileges, rights and even financial support in the form of bribery. The aim of this was to weaken their support for the rebellion against the Russian Empire.

Congress Poland was the largest supplier of zinc in Europe. The development of zinc industry took place at the beginning of the 19th century. It was mostly caused by the significant increase of demand for zinc mainly in industrialized countries of Western Europe.[23]

In 1899, Aleksander Ginsberg founded the company FOS (Fabryka Przyrządów Optycznych-"Factory of Optical Equipment") in Warsaw. It was the only firm in the Russian Empire which crafted and produced cameras, telescopes, objectives and stereoscopes. Following the outbreak of World War I the factory was moved to St. Petersburg.

See also

- Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland

- Grand Duchy of Posen

- History of Poland (1795–1918)

- Grand Duchy of Finland (1809–1917)

- Pale of Settlement

- Great Retreat – the withdrawal of Russian forces from Poland in 1915

Notes

a ^ Sources agree that after the fall of the January Uprising in 1864, the autonomy of Congress Poland was drastically reduced. They disagree however on whether the Kingdom of Poland, colloquially known as Congress Poland, as a state, was officially replaced by Vistula Land (Privislinsky Krai), a province of the Russian Empire, as many sources still use the term Congress Poland for the post-1864 period. The sources are also unclear as to when Congress Poland (or Vistula land) officially ended; some argue it ended when the German and Austro-Hungarian occupying authorities assumed control; others, that it ended with the creation of the Kingdom of Poland in 1916; finally, some argue that it occurred only with the creation of the independent Republic of Poland in 1918. Examples:

- Ludność Polski w XX Wieku = The Population of Poland in the 20th Century / Andrzej Gawryszewski. Warszawa: Polska Akademia Nauk, Instytut Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodorowania im. Stanisława Leszczyckiego, 2005 (Monografie; 5), p 539,

- (in Polish) Mimo wprowadzenia oficjalnej nazwy Kraj Przywiślański terminy Królestwo Polskie, Królestwo Kongresowe lub w skrócie Kongresówka były nadal używane, zarówno w języku potocznym jak i w niektórych publikacjach.

- Despite the official name Kraj Przywiślański terms such as, Kingdom of Poland, Congress Poland, or in short Kongresówka were still in use, both in everyday language and in some publications.

- POWSTANIE STYCZNIOWE, Encyklopedia Interia:

- (in Polish) po upadku powstania zlikwidowano ostatnie elementy autonomii Królestwa Pol. (łącznie z nazwą), przekształcając je w "Kraj Przywiślański";

- after the fall of the uprising last elements of autonomy of the Kingdom of Poland (including the name) were abolished, transforming it into the "Vistula land;"

- Królestwo Polskie. Encyclopedia WIEM:

- (in Polish) Królestwo Polskie po powstaniu styczniowym: Nazwę Królestwa Polskiego zastąpiła, w urzędowej terminologii, nazwa Kraj Przywiślański. Jednakże w artykule jest także: Po rewolucji 1905-1907 w Królestwie Polskim... i W latach 1914-1916 Królestwo Polskie stało się....

- Kingdom of Poland after the January Uprising: the name Kingdom of Poland was replaced, in official documents, by the name of Vistula land. However the same article also states: After the revolution 1905-1907 in the Kingdom of Poland and In the years 1914-1916 the Kingdom of Poland became....

- Królestwo Polskie, Królestwo Kongresowe, Encyklopedia PWN:

- (in Polish) 1915–18 pod okupacją niem. i austro-węgierską; K.P. przestało istnieć po powstaniu II RP (XI 1918).

- [Congress Poland was] under German and Austro-Hungarian occupation from 1915 to 1918; it was finally abolished after the creation of the Second Polish Republic in November 1918

References

- ↑ Polish: Królestwo Polskie [kruˈlɛstfɔ ˈpɔlskʲɛ]; Russian: Царство Польское, Tsarstvo Polskoye, Russian pronunciation: [kərɐˈlʲɛfstvə ˈpolʲskəje, ˈtsarstvə ˈpolʲskəje], Polish: Carstwo Polskie, translation: Tsardom of Poland

- ↑ Polish: Królestwo Kongresowe [kruˈlʲɛstfɔ kɔnɡrɛˈsɔvɛ]; Russian: Конгрессовая Польша

- 1 2 Nicolson, Harold George (2001). The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity, 1812-1822. New York: Grove Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-8021-3744-X.

- 1 2 Palmer, Alan Warwick (1997). Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph. Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-87113-665-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agnieszka Barbara Nance, Nation without a State: Imagining Poland in the Nineteenth Century, Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The University of Texas at Austin, pp. 169-188

- ↑ Henderson, WO (1964). Castlereagh et l'Europe, w: Le Congrès de Vienne et l'Europe. Paris: Bruxelles. p. 60.

- 1 2 Miłosz, Czesław (1983). The history of Polish literature. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 196. ISBN 0-520-04477-0. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- 1 2 3 Nicolson, Harold George (2001). The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity, 1812-1822. New York: Grove Press. pp. 179–180. ISBN 0-8021-3744-X. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ "Kingdom of Poland" (in Russian). The Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedia (1890–1906). Archived from the original on 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2006-07-27.

- 1 2 3 4 Ludwikowski, Rett R. (1996). Constitution-making in the region of former Soviet dominance. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-8223-1802-4.

- 1 2 "Królestwa Polskiego" (in Polish). Encyklopedia PWN. Retrieved 2006-01-19.

- ↑ Janowski, Maciej; Przekop, Danuta (2004). Polish Liberal Thought Before 1918. Budapest: Central European University Press. p. 74. ISBN 963-9241-18-0. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ Hugo Stumm, Russia's Advance Eastward, 1874, p. 140, note 1. Google Print

- ↑ Thomas Mitchell, Handbook for Travellers in Russia, Poland, and Finland, 1888, p. 460. Google Print

- ↑ Norman Davies, God's Playground: A History of Poland, Columbia University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-231-12819-3, Print, p. 278

- ↑ "Home Maddison". Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Życie gospodarcze Królestwa Polskiego w latach 1815-1830". Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Gospodarka w Królestwie Polskim od roku 1815 do początku XIX wieku.". Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Polityka gospodarcza - druckilubecki.pl". Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ↑ "The Augustów Canal". Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ↑ "Wyborcza.pl". Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ↑ "Łódź". Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ↑ http://www.aul.uni.lodz.pl/t/2005nr78/s.pdf

Further reading

- Davies, Norman. God's Playground. A History of Poland. Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present (Oxford University Press, 1982) pp 306–33

- Getka-Kenig, Mikolaj. "The Genesis of the Aristocracy in Congress Poland," Acta Poloniae Historica (2009), Issue 100, pp 79–112; covers the transition from feudalism to capitalism; the adjustment of the aristocracy's power and privilege from a legal basis to one of only social significance; the political changes instigated by the jurisdictional partitions and reorganizations of the state.

- Leslie, R. F. (1956). Polish politics and the Revolution of November 1830. Greenwood Press.

- Leslie, R. F. "Politics and economics in Congress Poland," Past and Present (1955), 8#1, pp. 43–63 in JSTOR

External links

Media related to Congress Poland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Congress Poland at Wikimedia Commons

Coordinates: 52°14′00″N 21°01′00″E / 52.2333°N 21.0167°E