Nanga Parbat

| Nanga Parbat | |

|---|---|

| نانگا پربت | |

Nanga Parbat, Astore, Gilgit Baltistan, Pakistan | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation |

8,126 m (26,660 ft) Ranked 9th |

| Prominence |

4,608 m (15,118 ft) Ranked 14th |

| Isolation | 189 kilometres (117 mi) |

| Listing |

Eight-thousander Ultra |

| Coordinates | 35°14′15″N 74°35′21″E / 35.23750°N 74.58917°ECoordinates: 35°14′15″N 74°35′21″E / 35.23750°N 74.58917°E |

| Geography | |

Nanga Parbat Location of Nanga Parbat  Nanga Parbat Location of Nanga Parbat | |

| Location |

Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan Nanga Parbat lies approx 27km west-southwest of Astore district, in the Gilgit–Baltistan region of Pakistan [1] |

| Parent range | Himalayas |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | July 3, 1953 by Hermann Buhl (First winter ascent 16 February 2016 by Simone Moro, Alex Txicon & Ali Sadpara) |

| Easiest route | Diamer District (West face) |

Nanga Parbat (Urdu: نانگا پربت [naːŋɡaː pərbət̪]) is the ninth highest mountain in the world at 8,126 metres (26,660 ft) above sea level. It is the western anchor of the Himalayas around which the Indus river skirts into the plains of Pakistan. It is in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan and is locally known as Diamir or Deo Mir (deo meaning "huge" and mir meaning "mountain").[2]

Nanga Parbat is one of the eight-thousanders, with a summit elevation of 8,126 metres (26,660 ft).[3] An immense, dramatic peak rising far above its surrounding terrain, Nanga Parbat is also a notoriously difficult climb. Numerous mountaineering deaths in the mid and early-20th century lent it the nickname "killer mountain".

Location

Nanga Parbat forms the western anchor of the Himalayan Range and is the westernmost eight-thousander. It lies just south of the Indus River in the Diamer District of Gilgit–Baltistan in Pakistan. Not far to the north is the western end of the Karakoram range.

Notable features

Nanga Parbat has tremendous vertical relief over local terrain in all directions.

To the south, Nanga Parbat boasts what is often referred to as the highest mountain face in the world: the Rupal Face rises 4,600 m (15,090 ft) above its base.[4] To the north, the complex, somewhat more gently sloped Rakhiot Flank rises 7,000 m (22,966 ft) from the Indus River valley to the summit in just 25 km (16 mi), one of the 10 greatest elevation gains in so short a distance on earth.

Nanga Parbat is one of only two peaks on earth that rank in the top twenty of both the highest mountains in the world, and the most prominent peaks in the world, ranking ninth and fourteenth respectively. The other is Mount Everest, which is first on both lists. It is also the second most prominent peak of the Himalayas, after Mount Everest. The key col for Nanga Parbat is Zoji La in Kashmir, which connects it to higher peaks in the remaining Himalaya-Karakoram range.[5]

Nanga Parbat along with Namcha Barwa on the Tibetan Plateau mark the west and east ends of the Himalayas.

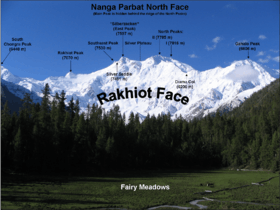

Layout of the mountain

The core of Nanga Parbat is a long ridge trending southwest–northeast. The ridge is an enormous bulk of ice and rock. It has three faces, Diamir face, Rakhiot, and Rupal. The southwestern portion of this main ridge is known as the Mazeno Wall, and has a number of subsidiary peaks. In the other direction, the main ridge arcs northeast at Rakhiot Peak (7,070 m / 23,196 ft). The south/southeast side of the mountain is dominated by the Rupal Face. The north/northwest side of the mountain, leading to the Indus, is more complex. It is split into the Diamir (west) face and the Rakhiot (north) face by a long ridge. There are a number of subsidiary summits, including North Peak (7,816 m / 25,643 ft) some 3 km north of the main summit. Near the base of the Rupal Face is a glacial lake called Latbo, above a seasonal shepherds' village of the same name.

Climbing history

Early attempts

Because of its accessibility, attempts to summit Nanga Parbat began very soon after it was discovered by Europeans.[4] In 1895 Albert F. Mummery led an expedition to the peak, and reached almost 6,100 m (20,000 ft) on the Diamir (West) Face,[6] but Mummery and two Gurkha companions later died reconnoitering the Rakhiot Face.

In the 1930s, Nanga Parbat became the focus of German interest in the Himalayas. The German mountaineers were unable to attempt Mount Everest, as only the British had access to Tibet. Initially German efforts focused on Kanchenjunga, to which Paul Bauer led two expeditions in 1930 and 1931, but with its long ridges and steep faces Kanchenjunga was more difficult than Everest and neither expedition made much progress. K2 was known to be harder still, and its remoteness meant that even reaching its base would be a major undertaking. Nanga Parbat was therefore the highest mountain accessible to Germans and also deemed reasonably possible by climbers at the time.[7]

The first German expedition to Nanga Parbat was led by Willy Merkl in 1932. It is sometimes referred to as a German-American expedition, as the eight climbers included Rand Herron, an American, and Fritz Wiessner, who would become an American citizen the following year. While the team were all strong climbers, none had Himalayan experience, and poor planning (particularly an inadequate number of porters), coupled with bad weather, prevented the team progressing far beyond the Rakhiot Peak northeast of the Nanga Parbat summit, reached by Peter Aschenbrenner and Herbert Kunigk, but they did establish the feasibility of a route via Rakhiot Peak and the main ridge.[8]

Merkl led another expedition in 1934, which was better prepared and financed with the full backing of the new Nazi government. Early in the expedition Alfred Drexel died, probably of high altitude pulmonary edema.[9] The Tyrolean climbers Peter Aschenbrenner and Erwin Schneider reached an estimated height of (7,895 m / 25,900 ft) on July 6, but were forced to return because of worsening weather. On July 7 they and 14 others were trapped by a storm at 7,480 m (24,540 ft). During the desperate retreat that followed, three famous German mountaineers, Uli Wieland, Willo Welzenbach and Merkl himself, and six Sherpas died of exhaustion, exposure and altitude sickness, and several more suffered severe frostbite. The last survivor to reach safety, Ang Tsering, did so having spent seven days battling through the storm.[10] It has been said that the disaster, "for sheer protracted agony, has no parallel in climbing annals."[11]

In 1937, Karl Wien led another expedition to the mountain, following the same route as Merkl's expeditions had done. Progress was made, but more slowly than before due to heavy snowfall. About 14 June seven Germans and nine Sherpas, almost the entire team, were at Camp IV below Rakhiot Peak when it was overrun by an avalanche. All sixteen men died.[12]

The Germans returned in 1938 led by Paul Bauer, but the expedition was plagued by bad weather, and Bauer, mindful of the previous disasters, ordered the party down before the Silver Saddle, halfway between Rakhiot Peak and Nanga Parbat summit, was reached.[13] The following year a small four man expedition, including Peter Aufschnaiter and Heinrich Harrer, explored the Diamir Face with the aim of finding an easier route. They concluded that the face was a viable route, but the Second World War intervened and the four men were interned by the British in Dehradun, India .[14] Harrer's escape and subsequent wanderings across the Tibetan Plateau became the subject of his book Seven Years in Tibet.

First ascent

Nanga Parbat was first climbed, via the Rakhiot Flank (East Ridge), on July 3, 1953 by Austrian climber Hermann Buhl,[15] a member of a German-Austrian team. The expedition was organized by the half-brother of Willy Merkl, Karl Herrligkoffer from Munich, while the expedition leader was Peter Aschenbrenner from Kufstein, who had participated in the 1932 and 1934 attempts. By the time of this expedition, 31 people had already died on the mountain.[16]

The final push for the summit was dramatic: Buhl continued alone for the final 1300 meters, after his companions had turned back. Under the influence of the drugs pervitin (based on the stimulant methamphetamine used by soldiers during World War II), padutin, and tea from coca leaves, he reached the summit dangerously late, at 7 pm, the climbing harder and more time-consuming than he had anticipated. His descent was slowed when he lost a crampon. Caught by darkness, he was forced to bivouac standing upright on a narrow ledge, holding a small handhold with one hand. Exhausted, he dozed occasionally, but managed to maintain his balance. He was also very fortunate to have a calm night, so he was not subjected to wind chill. He finally reached his high camp at 7 pm the next day, 40 hours after setting out.[17] The ascent was made without oxygen, and Buhl is the only man to have made the first ascent of an 8000 m peak alone.

Subsequent attempts and ascents

The second ascent of Nanga Parbat was via the Diamir Face, in 1962, by Germans Toni Kinshofer, Siegfried "Siegi" Löw, and A. Mannhardt. The route is now the "standard route" on the mountain. The Kinshofer route does not ascend the middle of the Diamir Face, which is threatened by avalanches from massive hanging glaciers. Instead it climbs a buttress on the left side of the face.

In 1970 the brothers Günther and Reinhold Messner made the third ascent of the mountain and the first ascent of the Rupal Face. They were unable to descend by their original route, and instead descended by the Diamir Face, making the first traverse of the mountain. Günther was killed in an avalanche on the Diamir Face. (Messner's account of this incident has been disputed. In 2005 Günther's remains were found on the Diamir Face.)

In 1971 Ivan Fiala and Michael Orolin summited Nanga Parbat via Buhl's 1953 route while other expedition members climbed the southeast peak (7,600 m / 24,925 ft) above the Silbersattel and the foresummit (7,850 m / 25,760 ft) above the Bazhin Gap.

In 1976 a team of four made the sixth summit via a new route on the Rupal Face (second ascent on this face), then named the Schell route after the Austrian team leader. The line had been plotted by Karl Herrligkoffer on a previous unsuccessful attempt.

In 1978 Reinhold Messner returned to the Diamir Face and achieved the first completely solo ascent (i.e., always solo above base camp) of an 8,000 m peak.

In 1984 the French climber Lilliane Barrard became the first woman to climb Nanga Parbat, along with her husband Maurice Barrard.

In 1985, Jerzy Kukuczka, Zygmunt Heinrich, Slawomir Lobodzinski (all Polish), and Carlos Carsolio (Mexico) climbed up the Southeast Pillar (or Polish Spur) on the right-hand side of the Rupal Face, reaching the summit July 13. It was Kukuczka's 9th 8000m summit.[18]

Also in 1985, a Polish women's team climbed the peak via the 1962 German Diamir Face route. Wanda Rutkiewicz, Krystyna Palmowska, and Anna Czerwinska reached the summit on July 15.[18]

"Modern" superalpinism was brought to Nanga Parbat in 1988 with an unsuccessful attempt or two on the Rupal Face by Barry Blanchard, Mark Twight, Ward Robinson, and Kevin Doyle.[19]

2005 saw a resurgence of lightweight, alpine-style attempts on the Rupal Face:

- In August 2005, Pakistani military helicopters rescued Slovenian mountaineer Tomaž Humar, who was stuck under a narrow ice ledge at 5,900 m (19,400 ft) for six days. It is believed to be one of the few successful rescues carried out at such high altitude.[20]

- In September 2005, Vince Anderson and Steve House did an extremely lightweight, fast ascent of a new, direct route on the face, earning high praise from the climbing community.[21]

- On July 17 or 18, 2006, José Antonio Delgado from Venezuela died a few days after reaching the summit, where he was caught by bad weather for six days and was unable to make his way down. He is the only Venezuelan climber, and one of few Latin Americans, to have reached the summit of five eight-thousanders.[22] Part of the expedition and the rescue efforts at base camp were captured on video, as Delgado was the subject of a pilot for a mountaineering television series.[22] Explorart Films, the production company, later developed the project into a feature documentary film called Beyond the Summit, which was scheduled to be released in South America in January 2008.[23]

- On July 15, 2008, Italian alpinist Karl Unterkircher fell into a crevasse during an attempt to open a new route to the top with Walter Nones and Simon Kehrer. Unterkircher died, but Kehrer and Nones were rescued by the Pakistani Army.[24]

- On July 12, 2009, after reaching the summit, South Korean climber Go Mi-Young fell off a cliff on the descent in bad weather in her race to be the first woman to climb all 14 eight-thousanders.[25]

- On July 15, 2012 Scottish mountaineers Sandy Allan and Rick Allen made the first ascent of Nanga Parbat via the 10 km-long Mazeno Ridge,[26] and in April 2013 were awarded the Piolet d'Or for their achievement.[27]

Winter climbing

Nanga Parbat was first successfully climbed in winter on February 26, 2016, by a team consisting of Ali Sadpara, Alex Txikon, and Simone Moro.[28][29]

Previous attempts:

- 1988/89 - Polish 12-member expedition KW Zakopane under the leadership of Maciej Berbeka. They first attempted the Rupal Face and then the Diamir Face. On the Messner route, Maciej Berbeka, Piotr Konopka, and Andrzej Osika reached an elevation of about 6500-6800 m.

- 1990/91 - Polish-English expedition under the leadership of Maciej Berbeka reached the height of 6600m on the Messner route, and then Andrzej Osika and John Tinker by the Schell route up the Rupal Face reached a height of 6600 m.

- 1991/92 - Polish expedition KW Zakopane under the leadership of Maciej Berbeka from the Rupal valley. This attack in alpine style on the Schell route reached the height of 7000 m.

- 1992/93 - French expedition Eric Monier and Monique Loscos - Schell route on the Rupal Face. They came to BC on December 20. Eric reached 6500 m on January 9 and on January 13 the expedition was abandoned.

- 1996/97 - two expeditions:

- Polish expedition led by Andrzej Zawada from the Diamir valley, Kinshofer route. During the summit attempt by the team of Zbigniew Trzmiel and Krzysztof Pankiewicz, Trzmiel reached a height of 7800 m. The assault was interrupted because of frostbite. After descending to the base camp, both climbers were evacuated by helicopter to a hospital.

- British expedition led by Victor Saunders, taking the Kinshofer route on the Diamir Face. Victor Saunders, Dane Rafael Jensen, and Pakistani Ghulam Hassan reached the height of 6000 m.

- 1997/98 - Polish expedition led by Andrzej Zawada from the Diamir valley, Kinshofer route. Expedition reached the height of 6800 m, encountered an unusually heavy snowfall. A falling stone broke Ryszard Pawłowski's leg.

- 2004/05 - Austrian expedition by brothers Wolfgang and Gerfried Göschl via the Kinshofer route on the Diamir Face reached the height of 6500 m.

- 2006/07 - Polish HiMountain expedition on the Schell route on the Rupal Face. Expedition led by Krzysztof Wielicki, with Jan Szulc, Artur Hajzer, Dariusz Załuski, Jacek Jawień, Jacek Berbeka, Przemysław Łoziński, and Robert Szymczak reached a height of 7000 m.

- 2007/08 - Italian Simone La Terra started climbing solo at the beginning of December, reaching a height of 6000 m.

- 2008/09 - Polish expedition on the Diamir side. Jacek Teler (leader) and Jarosław Żurawski. Deep snow prevented them from hauling their equipment to the base of the face, forcing the base camp to be placed five kilometres earlier. Camp I set at an altitude of 5400 m.

- 2010/11 - two expeditions:

- Sergei Nikolayevich Cygankow in a solo expedition on the Kinshofer route on the Diamir Face reached 6000 m. He contracted pulmonary edema and ended the expedition.

- Tomasz Mackiewicz and Marek Klonowski - Polish expedition "Justice for All - Nanga Dream" by Kinshofer route on the Diamir side reached 5100 m.

- 2011/12 - three expeditions:

- Tomasz Mackiewicz, Marek Klonowski and "Krzaq" - Polish expedition "Justice for All - Nanga Dream" by Kinshofer route on the Diamir side reached 5500 m.

- Denis Urubko and Simone Moro first Diamir side on the Kinshofer route, and then by Messner route in year 2000 reached a height of 6800 m.

- 2012/13 - four expeditions:

- Frenchman Joël Wischnewski solo on the Rupal Face in an alpine style. He was lost in February and his body was found in September at an altitude of about 6100 m.[30] He went missing after February 6 and was probably hit by an avalanche.[31]

- Italy's Daniele Nardi and French Elisabeth Revol - Mummery Rib on the Diamir reached the height of 6450 m.

- Hungarian-American expedition: David Klein, Zoltan Acs and Ian Overton. Zoltan has suffered frostbite while reaching the base and did not participate in the further ascent. David and Ian reached the height of about 5400 m on the Diamir Face.

- Tomasz Mackiewicz and Marek Klonowski - Polish expedition "Justice for All - Nanga Dream" by Schell route on the Rupal Face. Marek Klonowski reached a height of 6600 m. On February 7, 2013 Tomasz Mackiewicz in a lone attack reached a height of 7400 m.

- 2013/14 - four expeditions:

- Italian Simone Moro, German David Göttler, and Italian Emilio Previtali - Schell route on the Rupal Face. Expedition cooperated with Polish expedition. David Göttler, on February 28, set Camp IV at about 7000 m. On March 1, together with Tomasz Mackiewicz reached an altitude of about 7200 m. On the same day David and Simone decided to end the expedition.[32]

- Tomasz Mackiewicz, Marek Klonowski, Jacek Teler, Paweł Dunaj, Michał Obrycki, Michał Dzikowski - Polish expedition "Justice for All - Nanga Dream" by Schell route on the Rupal Face. Expedition cooperated with Italian-German expedition. March 1, Tomasz Mackiewicz and David Göttler reached an altitude of about 7200 m. On March 8, at a height of about 5000 m, Paweł Dunaj and Michał Obrycki were hit by an avalanche. Both were roughed up and suffered fractures. The rescue operation was successful.

- German Ralf Dujmovits on the Diamir Face, by Reinhold Messner route in 1978 (as a filmmaker this expedition Pole Dariusz Załuski - he had no plan of summit attack). December 30 both came at 5500 m. On January 2, because of the serac threat, Dujmovits decided to abandon the expedition.

- Italy's Daniele Nardi. Solo expedition from the Diamir side on Mummery Rib. Italy set Camp I at 4900 m and reached an altitude of about 5450 m. On March 1 he decided to end the expedition.

- 2014/15 - five expeditions:

- Pole Tomasz Mackiewicz and Frenchwoman Elisabeth Revol - Nanga Parbat Winter Expedition 2014/2015. The north-west Diamir Face, unfinished route by Messner-Hanspeter 2000. They reached 7800 m.[33]

- Italian Daniele Nardi planning the trip solo summit Mummery Rib on the Diamir Face, accompanied by Roberto Delle Monache (photographer) and Federico Santinii (filmmaker)

- A 4-member Russian expedition - Nikolay Totmjanin, Sergei Kondraszkin, Valery Szamało, Victor Smith - Schell route on the Rupal Face. They reached 7150 m.[34]

- A three-person expedition Iran - Reza Bahador, Iraj Maani, and Mahmoud Hashemi

- 2015/16 - five expeditions:

- Nanga Light 2015/16 with Tomasz, Elisabeth Revol, and Arsalan Ahmed Ansari. On January 22, Mackiewicz and Revol reached 7500 m, but they were forced to cancel their attempt for the summit due to excessive cold.[35]

- Nanga Stegu Revolution 2015/16 with Adam Bielecki and Jacek Czech. After an accident Bielecki's injuries after a fall, forced the team down.

- "Nanga Dream - Justice for All" - under the lead of Marek Klonowski with Paweł Dunaj, Paweł Witkowski, Tomasz Dziobkowski, Michał Dzikowski, Paweł Kudła, Piotr Tomza and Karim Hayat and Safdar Karim. As of January 19, 2016 still at around 7000 m, trying to reach the summit.

- International team consisting of Alex Txikon, Daniele Nardi, and Ali Sadpara.

- Italian team consisting of Simone Moro and Tamara Lunger.

- The two above mentioned teams (with the exception of Daniele Nardi) joined their efforts and on February 26, 2016 Italian Simone Moro, Basque Alex Txikon, and Ali Sadpara reached the summit, marking the first winter ascent of Nanga Parbat, while Tamara Lunger stopped short of the summit due to nausea and extreme cold, giving an interview to Noor abbas Qureshi, she told that she tried her best, but her health didn't allow her to reach the summit.

Taliban attack

On June 23, 2013, about 15 extremist militants wearing Gilgit Scouts uniforms shot to death ten foreign climbers (one Lithuanian, three Ukrainians, two Slovakians, two Chinese, one Chinese-American, and one Nepali)[36] and one Pakistani guide at Base Camp. Another foreign victim was injured. The attack occurred at around 1 am and was claimed by a local branch of the Taliban. (Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan).[37][38]

Appearances in literature and film

In the first chapter of Mistress of Mistresses, by E.R. Eddison, the narrator compares his now deceased compatriot, Lessingham, to Nanga Parbat in a descriptive passage:

- "I remember, years later, his describing to me the effect of the sudden view you get of Nanga Parbat from one of those Kashmir valleys; you have been riding for hours among quiet richly wooded scenery, winding up along the side of some kind of gorge, with nothing very big to look at, just lush, leafy, pussy-cat country of steep hillsides and waterfalls; then suddenly you come round a corner where the view opens up the valley, and you are almost struck senseless by the blinding splendour of that vast face of ice-hung precipices and soaring ridges, sixteen thousand feet from top to toe, filling a whole quarter of the heavens at a distance of, I suppose, only a dozen miles. And now, whenever I call to mind my first sight of Lessingham in that little daleside church so many years ago, I think of Nanga Parbat." (Mistress of Mistresses, 1935, p.2-3)

Jonathan Neale wrote a book about the 1934 climbing season on Nanga Parbat called Tigers of the Snow. He interviewed many old Sherpas, including Ang Tsering, the last man off Nanga Parbat alive in 1934. The book attempts to narrate what went wrong on the expedition, set against mountaineering history of the early twentieth century, the background of German politics in the 1930s, and the hardship and passion of life in the Sherpa valleys.[39]

Nanga Parbat is a movie by Joseph Vilsmaier about the 1970 expedition of brothers Günther Messner and Reinhold Messner.[40] Donald Shebib's 1986 film The Climb covers the story of Hermann Buhl making the first ascent.[41]

Nearby peaks

See also

References

- ↑ "Nanga Parbat". Britannica. Retrieved 2015-04-12.

- ↑ The Pamirs and the Source of the Oxus. (1896) George Nathaniel Curzon. Royal Geographical Society, London, p. 16.

- ↑ "Nanga Parbat | mountain, Jammu and Kashmir". Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- 1 2 Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. US: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 261. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- ↑ "Zoji La". Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Nanga Parbat: 9th Highest Mountain in the World". climbing.about.com. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ↑ Neale, pp. 63–64

- ↑ Mason, pp. 226–228

- ↑ Neale, pp. 123-130

- ↑ Mason pp. 230-233

- ↑ Simpson, pp. 196–197

- ↑ Neale, pp. 212-213

- ↑ Mason pp. 236-237

- ↑ Mason pp. 238-239

- ↑ nangaroutesnew.pdf, Eberhard Jurgalski (rosemon), last updated 17 June 2010, retrieved from http://www.8000ers.com/cms/en/nanga-parbat-general-info-197.html 22 July 2011.

- ↑ This includes two British climbers who disappeared low on the mountain in December 1950. They were studying conditions on the Rakhiot glacier, not attempting the summit. See Mason p. 306.

- ↑ Sale & Cleare, pp. 72–73

- 1 2 "Basecamp", Climbing Magazine (93): 22, December 1995, ISSN 0045-7159

- ↑ Twight, Mark (2001). Kiss or kill: confessions of a serial climber. Seattle: The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0-89886-887-4.

- ↑ "Climber rescued from major peak". BBC News. 10 August 2005. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ↑ Alpinist 15 on the Anderson/House ascent

- 1 2 NANGA PARBAT 2006

- ↑ Mas Alla de la Cumbre - Beyond the Summit

- ↑ "Italian climbers rescued from Pakistan's Killer Mountain, Nanga Parbat". The Guardian. 25 July 2008. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "Korean Alpinist Go Mi-sun Dies After Fall on Nanga Parbat". himalman.wordpress.com. 13 July 2009. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "Coming down Nanga Parbat as hard as going up". dawn.com. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "Aberdeen and Newtonmore climbers win Piolet d'Or". BBC News. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ Szczepanski, Dominik. "Nanga Parbat zdobyta w zimie po raz pierwszy!". Sport.pl.

- ↑ "Alpinismo, impresa su Nanga Parbat".

- ↑ http://www.steepboard.fr/

- ↑ http://altitudepakistan.blogspot.com/2013/11/winter-nanga-parbat-body-of-joel.html

- ↑ http://www.explorersweb.com/everest_k2/news.php?url=winter-2014-climbers-at-7000m-on-nanga-p_139360434

- ↑ http://himalaya-light.over-blog.com/article-nanga-parbat-en-hiver-125432289.html

- ↑ http://altitudepakistan.blogspot.fr/2015/02/winter-2015-russians-wrap-up-their.html

- ↑ http://altitudepakistan.blogspot.fr/2016/01/winter-2016-its-over-for-nanga-light.html

- ↑ Khan, Zarar; Abbot, Sebastian. "Militants kill 9 foreign tourists, 1 Pakistani". Yahoo News. AP. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

The foreigners who were killed included five Ukrainians, three Chinese and one Russian, said Pakistani Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan.

- ↑ "Pakistan Gunmen Kill 11 Foreign Mountain Climbers Preparing Nanga Parbat Ascent". The Huffington Post. 23 June 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ↑ "Massacre at Nanga Parbat Diamir BC - Terrorists Kill 10". Altitude Pakistan. 23 June 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ↑ "Tigers of the Snow". Macmillan Publishers. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ Official film website

- ↑ "The Climb (1986)". IMDB. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

Sources

- The German obsession with Nanga Parbat - War Life | Nathan Morley

- Mason, Kenneth (1987) [1955 published by Rupert Hart-Davis]. Abode of Snow: A History of Himalayan Exploration and Mountaineering From Earliest Times to the Ascent of Everest. Diadem Books. ISBN 978-0-906371-91-6.

- Neale, Jonathan (2002). Tigers of the Snow. St Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-26623-5.

- Sale, Richard; Cleare, John (2000). Climbing the World's 14 Highest Mountains: The History of the 8,000-Meter Peaks. Seattle: Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-727-5.

- Simpson, Joe (1997). Dark Shadows Falling. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-04368-4.

- Herrligkoffer, Karl M., Nanga Parbat. Elek Books, 1954.

- Irving, R. L. G., Ten Great Mountains (London, J. M. Dent & Sons, 1940)

- Ahmed Hasan Dani, Chilas: The City of Nanga Parvat (Dyamar). 1983. ASIN B0000CQDB2

- Alpenvereinskarte "Nanga Parbat", 1:50,000, Deutsche Himalaya Expedition 1934.

- Andy Fanshawe and Stephen Venables, Himalaya Alpine-Style, Hodder and Stoughton, 1995.

- Audrey Salkeld (editor), World Mountaineering, Bulfinch, 1998.

- American Alpine Journal

- Himalayan Index

- DEM files for the Himalaya (Corrected versions of SRTM data)

- Guardian International story on Gunther Messner

- Climbing magazine, April 2006.

Further reading

- Buhl, Herman (1956). Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-26498-5.

- Messner, Reinhold, Solo Nanga Parbat, London, Kale and Ward, 1980, ISBN 0-7182-1250-9 (Britain), ISBN 0-19-520196-5 (USA)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nanga Parbat. |

- Nanga Parbat on Peakware

- Nanga Parbat on summitpost.org

- Nanga Parbat on Himalaya-Info.org (German)

- A mountain list ranked by local relief and steepness showing Nanga Parbat as the World #1

- A Quick approach through lovely meadows leads to the base camp of NANGA PARBAT’s enormous RUPAL face

- Pictures of the Rupal Facce taken by Joël Wischnewski in 2013