Chitwan National Park

| Chitwan National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

Bishazari Tal in Chitwan National Park | |

|

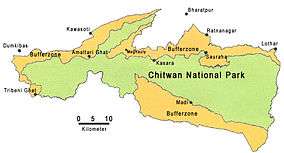

Map of Chitwan National Park | |

| Location | Nepal |

| Nearest city | Bharatpur |

| Coordinates | 27°30′0″N 84°20′0″E / 27.50000°N 84.33333°ECoordinates: 27°30′0″N 84°20′0″E / 27.50000°N 84.33333°E |

| Area | 932 km2 (360 sq mi) |

| Established | 1973 |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | vii, ix, x |

| Designated | 1984 (8th session) |

| Reference no. | 284 |

| State Party |

|

| Region | Asia |

Chitwan National Park (Nepali: चितवन राष्ट्रिय निकुञ्ज; formerly Royal Chitwan National Park) is the first national park in Nepal. It was established in 1973 and granted the status of a World Heritage Site in 1984. It covers an area of 932 km2 (360 sq mi) and is located in the subtropical Inner Terai lowlands of south-central Nepal in the districts of Nawalparasi, Parsa, Chitwan and Makwanpur. In altitude it ranges from about 100 m (330 ft) in the river valleys to 815 m (2,674 ft) in the Churia Hills.[1]

In the north and west of the protected area the Narayani-Rapti river system forms a natural boundary to human settlements. Adjacent to the east of Chitwan National Park is Parsa Wildlife Reserve, contiguous in the south is the Indian Tiger Reserve Valmiki National Park. The coherent protected area of 2,075 km2 (801 sq mi) represents the Tiger Conservation Unit (TCU) Chitwan-Parsa-Valmiki, which covers a 3,549 km2 (1,370 sq mi) huge block of alluvial grasslands and subtropical moist deciduous forests.[2]

History

Since the end of the 19th century Chitwan – Heart of the Jungle – used to be a favorite hunting ground for Nepal’s ruling class during the cool winter seasons. Until the 1950s, the journey from Kathmandu to Nepal’s south was arduous as the area could only be reached by foot and took several weeks. Comfortable camps were set up for the feudal big game hunters and their entourage, where they stayed for a couple of months shooting hundreds of tigers, rhinocerosses, leopards and sloth bears.[3]

In 1950, Chitwan’s forest and grasslands extended over more than 2,600 km2 (1,000 sq mi) and was home to about 800 rhinos. When poor farmers from the mid-hills moved to the Chitwan Valley in search of arable land, the area was subsequently opened for settlement, and poaching of wildlife became rampant. In 1957, the country's first conservation law inured to the protection of rhinos and their habitat. In 1959, Edward Pritchard Gee undertook a survey of the area, recommended creation of a protected area north of the Rapti River and of a wildlife sanctuary south of the river for a trial period of ten years.[4] After his subsequent survey of Chitwan in 1963, this time for both the Fauna Preservation Society and the International Union for Conservation of Nature, he recommended extension of the sanctuary to the south.[5]

By the end of the 1960s, 70% of Chitwan’s jungles were cleared using DDT, thousands of people had settled there, and only 95 rhinos remained. The dramatic decline of the rhino population and the extent of poaching prompted the government to institute the Gaida Gasti – a rhino reconnaissance patrol of 130 armed men and a network of guard posts all over Chitwan. To prevent the extinction of rhinos the Chitwan National Park was gazetted in December 1970, with borders delineated the following year and established in 1973, initially encompassing an area of 544 km2 (210 sq mi).[6]

In 1977, the park was enlarged to its present area of 932 km2 (360 sq mi). In 1997, a bufferzone of 766.1 km2 (295.8 sq mi) was added to the north and west of the Narayani-Rapti river system, and between the south-eastern boundary of the park and the international border to India.[1]

The park’s headquarters is in Kasara. Close-by the gharial and turtle conservation breeding centres have been established. In 2008, a vulture breeding centre was inaugurated aiming at holding up to 25 pairs of each of the two Gyps vultures species now critically endangered in Nepal - the Oriental white-backed vulture and the slender-billed vulture.

Climate

Chitwan has a tropical monsoon climate with high humidity all through the year.[3] The area is located in the central climatic zone of the Himalayas, where monsoon starts in mid June and eases off in late September. During these 14–15 weeks most of the 2,500 mm yearly precipitation falls – it is pouring with rain. After mid-October the monsoon clouds have retreated, humidity drops off, and the top daily temperature gradually subsides from ±36 °C / 96.8 °F to ±18 °C / 64.5 °F. Nights cool down to 5 °C / 41.0 °F until late December, when it usually rains softly for a few days. Then temperatures start rising gradually.

Vegetation

The typical vegetation of the Inner Terai is Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests with predominantly sal trees covering about 70% of the national park area. The purest stands of sal occur on well drained lowland ground in the centre. Along the southern face of the Churia Hills sal is interspersed with chir pine (Pinus roxburghii). On northern slopes sal associates with smaller flowering tree and shrub species such as beleric (Terminalia bellirica), rosewood (Dalbergia sissoo), axlewood (Anogeissus latifolia), elephant apple (Dillenia indica), grey downy balsam (Garuga pinnata) and creepers such as Bauhinia vahlii and Spatholobus parviflorus.

Seasonal bushfires, flooding and erosion evoke an ever-changing mosaic of riverine forest and grasslands along the river banks. On recently deposited alluvium and in lowland areas groups of catechu (Acacia catechu) with rosewood (Dalbergia sissoo) predominate, followed by groups of kapok (Bombax ceiba) with rhino apple trees (Trewia nudiflora), the fruits of which rhinos savour so much.[7] Understorey shrubs of velvety beautyberry (Callicarpa macrophylla), hill glory bower (Clerodendrum sp.) and gooseberry (Phyllanthus emblica) offer shelter and lair to a wide variety of species.

Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands cover about 20% of the park’s area. More than 50 species are found here including some of the world’s tallest grasses like the elephant grass called Saccharum ravennae, giant cane (Arundo donax), khagra reed (Phragmites karka) and several species of true grasses. Kans grass (Saccharum spontaneum) is one of the first grasses to colonise new sandbanks and to be washed away by the yearly monsoon floods.[8]

Fauna

The wide range of vegetation types in the Chitwan National Park is haunt of more than 700 species of wildlife and a not yet fully surveyed number of butterfly, moth and insect species. Apart from king cobra and rock python, 17 other species of snakes, starred tortoise and monitor lizards occur. The Narayani-Rapti river system, their small tributaries and myriads of oxbow lakes is habitat for 113 recorded species of fish and mugger crocodiles. In the early 1950s, about 235 gharials occurred in the Narayani River. The population has dramatically declined to only 38 wild gharials in 2003. Every year gharial eggs are collected along the rivers to be hatched in the breeding center of the Gharial Conservation Project, where animals are reared to an age of 6–9 years. Every year young gharials are reintroduced into the Narayani-Rapti river system, of which sadly only very few survive.[9]

Mammals

_-_Koshyk.jpg)

.jpg)

The Chitwan National Park is home to at least 68 species of mammals.[10] The "king of the jungle" is the Bengal tiger. The alluvial floodplain habitat of the Terai is one of the best tiger habitats anywhere in the world. Since the establishment of Chitwan National Park the initially small population of about 25 individuals increased to 70–110 in 1980. In some years this population has declined due to poaching and floods. In a long-term study carried out from 1995–2002 tiger researchers identified a relative abundance of 82 breeding tigers and a density of 6 females per 100 km2.[11] Information obtained from camera traps in 2010 and 2011 indicated that tiger density ranged between 4.44 and 6.35 individuals per 100 km2. They offset their temporal activity patterns to be much less active during the day when human activity peaked.[12]

Leopards are most prevalent on the peripheries of the park. They co-exist with tigers, but being socially subordinate are not common in prime tiger habitat.[13] In 1988, a clouded leopard was captured and radio-collared outside the protected area, and released into the park but did not stay.[14]

Chitwan is considered to have the highest population density of sloth bears with an estimated 200 to 250 individuals. Smooth-coated otters inhabit the numerous creeks and rivulets. Bengal foxes, spotted linsangs and honey badgers roam the jungle for prey. Striped hyenas prevail on the southern slopes of the Churia Hills.[15] During a camera trapping survey in 2011, wild dogs were recorded in the southern and western parts of the park, as well as golden jackals, fishing cats, jungle cats, leopard cats, large and small Indian civets, Asian palm civets, crab-eating mongooses and yellow-throated martens.[16]

Rhinoceros: since 1973 the population has recovered well and increased to 544 animals around the turn of the century. To ensure the survival of the endangered species in case of epidemics animals are translocated annually from Chitwan to the Bardia National Park and the Sukla Phanta Wildlife Reserve since 1986. However, the population has repeatedly been jeopardized by poaching: in 2002 alone, poachers killed 37 individuals in order to saw off and sell their valuable horns.[6] Chitwan has the largest population of Indian rhinoceros in Nepal, estimated at 605 individuals out of 645 in total in the country.[17]

From time to time wild elephant bulls find their way from Valmiki National Park into the valleys of the park, apparently in search of elephant cows willing to mate.

Gaurs spend most of the year in the less accessible Churia Hills in the south of the national park. But when the bush fires ease off in springtime and lush grasses start growing up again, they descend into the grassland and riverine forests to graze and browse. The Chitwan population of the world's largest wild cattle species has increased from 188 to 368 animals in the years 1997 to 2016. Furthermore, 112 animals were counted in the adjacent Parsa Wildlife Reserve. The animals move freely between these parks.[18]

Apart from numerous wild boars also sambar deer, red muntjac, hog deer and herds of chital inhabit the park. Four-horned antelopes reside predominantly in the hills. Rhesus monkeys, hanuman langurs, Indian pangolins, Indian porcupines, several species of flying squirrels, black-naped hares and endangered hispid hares are also present.[15]

Birds

_in_Hodal_W_IMG_6277.jpg)

Every year dedicated bird watchers and conservationists survey bird species occurring all over the country. In 2006 they recorded 543 species in the Chitwan National Park, much more than in any other protected area in Nepal and about two-thirds of Nepal's globally threatened species. Additionally, 20 black-chinned yuhina, a pair of Gould's sunbird, a pair of blossom-headed parakeet and one slaty-breasted rail, an uncommon winter visitor, were sighted in spring 2008.[19]

Especially the park’s alluvial grasslands are important habitats for the critically endangered Bengal florican, the vulnerable lesser adjutant, grey-crowned prinia, swamp francolin and several species of grass warblers. In 2005 more than 200 slender-billed babblers were sighted in three different grassland types.[20] The near threatened Oriental darter is a resident breeder around the many lakes, where also egrets, bitterns, storks and kingfishers abound.

The park is one of the few known breeding sites of the globally threatened spotted eagle.

Peafowl and jungle fowl scratch their living on the forest floor.

Apart from the resident birds about 160 migrating and vagrant species arrive in Chitwan in autumn from northern latitudes to spend the winter here, among them the greater spotted eagle, eastern imperial eagle and Pallas's fish-eagle. Common sightings include brahminy ducks and goosanders. Large flocks of bar-headed geese just rest for a few days in February on their way north.

As soon as the winter visitors have left in spring, the summer visitors arrive from southern latitudes. The calls of cuckoos herald the start of spring. The colourful Bengal pittas and several sunbird species are common breeding visitors during monsoon. Among the many flycatcher species the paradise flycatcher with his long undulating tail in flight is a spectacular sight.

Tourism

Chitwan National Park is one of Nepal’s most popular tourist destinations. In 1989 more than 31,000 people visited the park, and ten years later already more than 77,000.

There are two main entrances to visit the Chitwan National Park: the tourist town of Sauraha in the east and the tranquil Tharu settlement of Meghauli Village in the west.

Sauraha is a well-known spot for package tourists and offers a choice of hundreds of hotels, lodges, restaurants and agencies. Meghauli has recently opened up as a tourist destination with the creation of the Tharu Homestay Program to promote the village tourism in the area, offering a more authentic and intimate jungle experience. It now has also a couple of budget guest houses and seven jungle lodges to cater to all budgets.

Both destinations can be reached from Narayangarh in less than two hours.

Literature

- Bird Conservation Nepal (2006). Birds of Chitwan. Checklist of 543 reported species. Published in cooperation with Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and Participatory Conservation Programme II, Kathmandu.

- Gurung, K. K., Singh R. (1996). Field Guide to the Mammals of the Indian Subcontinent. Academic Press, San Diego, ISBN 0-12-309350-3

Media coverage

The park's unique rhino herd was featured on The Jeff Corwin Experience in season 2, episode 11.

A tour experience on jeep safari, walking trek and village tour on Travel Photo Discovery on Chitwan National Park.

References

- 1 2 Bhuju, U. R., Shakya, P. R., Basnet, T. B., Shrestha, S. (2007). Nepal Biodiversity Resource Book. Protected Areas, Ramsar Sites, and World Heritage Sites. Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Ministry of Environment, Science and Technology, in cooperation with United Nations Environment Programme, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Kathmandu, ISBN 978-92-9115-033-5

- ↑ Wikramanayake, E.D., Dinerstein, E., Robinson, J.G., Karanth, K.U., Rabinowitz, A., Olson, D., Mathew, T., Hedao, P., Connor, M., Hemley, G., Bolze, D. (1999) Where can tigers live in the future? A framework for identifying high-priority areas for the conservation of tigers in the wild. Archived March 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. In: Seidensticker, J., Christie, S., Jackson, P. (eds.) Riding the Tiger. Tiger Conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. hardback ISBN 0-521-64057-1, paperback ISBN 0-521-64835-1.

- 1 2 Gurung, K. K. (1983). Heart of the Jungle: the Wildlife of Chitwan, Nepal. André Deutsch, London.

- ↑ Gee, E. P. (1959). Report on a survey of the rhinoceros area of Nepal. Oryx 5: 67–76.

- ↑ Gee, E. P. (1963). Report on a brief survey of the wildlife resources of Nepal, including rhinoceros. Oryx 7: 67–76.

- 1 2 Adhikari, T. R. (2002). The curse of success. Habitat Himalaya - A Resources Himalaya Factfile, Volume IX, Number 3.

- ↑ Dinerstein, E.; Wemmer, C. M. (1988). "Fruits Rhinoceros Eat: Dispersal of Trewia Nudiflora (Euphorbiaceae) in Lowland Nepal". Ecology. 69 (6): 1768–1774. doi:10.2307/1941155.

- ↑ Shrestha, B. K., Dangol, D. R. (2006). Change in Grassland Vegetation in the Northern Part of Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Scientific World, Vol. 4, No. 4: 78–83.

- ↑ Priol, P. (2003). Gharial field study report. A report submitted to Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- ↑ "Welcome to Chitwan National Park". www.chitwannationalpark.gov.np. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ↑ Barlow, A.; McDougal, C.; Smith, J. L. D.; Gurung, B.; Bhatta, S. R.; Kumal, S.; Mahato, B.; Tamang, D. B. (2009). "Temporal Variation in Tiger (Panthera tigris) Populations and its Implications for Monitoring". Journal of Mammalogy. 90 (2): 472–478. doi:10.1644/07-mamm-a-415.1.

- ↑ Carter, N. H.; Shrestha, B. K.; Karki, J. B.; Pradhan, N. M. B. & J. Liu (2012). "Coexistence between wildlife and humans at fine spatial scales" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (38): 15360–15365. doi:10.1073/pnas.1210490109.

- ↑ McDougal, C (1988). "Leopard and Tiger Interactions at Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 85: 609–610.

- ↑ Dinerstein, E.; Mehta, J. N. (1989). "The clouded leopard in Nepal". Oryx. 23 (4): 199–201. doi:10.1017/S0030605300023024.

- 1 2 Jnawali, S. R., Baral, H. S., Lee, S., Acharya, K. P., Upadhyay, G. P., Pandey, M., Shrestha, R., Joshi, D., Lamichhane, B. R., Griffiths, J., Khatiwada, A. P., Subedi, N. and Amin, R. (compilers) (2011). The Status of Nepal’s Mammals: The National Red List Series. Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- ↑ Thapa, K.; Kelly, M. J.; Karki, J. B.; Subedi, N. (2013). "First camera trap record of pack hunting dholes in Chitwan National Park, Nepal". Canid Biology & Conservation. 16 (2): 4–7.

- ↑ Kathmandu (26 January 2016). "Nepal to gift 2 rhinos to China". The Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ Bison population increasing in Chitwan National Park (2016). https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/bison-population-increasing-cnp/

- ↑ Giri, T.; Choudhary, H. (2008). "Additional Sightings". Danphe. 17 (2): 6.

- ↑ Baral, H. S.; Chaudhary, D. B. (2006). "Status and Distribution of Slender-billed babbler Turdoides longirostris in Chitwan National Park, central Nepal". Danphe. 15 (4): 1–6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chitwan National Park. |

Chitwan National Park travel guide from Wikivoyage

Chitwan National Park travel guide from Wikivoyage- Information of Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Nepal

- Chitwan National Park

- BirdLife IBA factsheet : Chitwan National Park

- Vulture Breeding Centre in Chitwan National Park