Royal Blue (train)

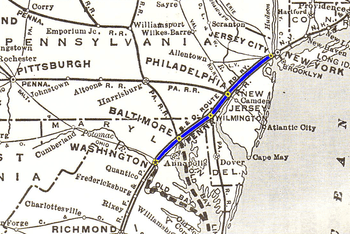

The Royal Blue was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O)'s flagship passenger train between New York City and Washington, D.C., in the United States, beginning in 1890. The Baltimore-based B&O also used the name between 1890 and 1917 for its improved passenger service between New York and Washington launched in the 1890s, collectively dubbed the Royal Blue Line. Using variants such as the Royal Limited and Royal Special for individual Royal Blue trains, the B&O operated the service in partnership with the Reading Railroad and the Central Railroad of New Jersey. Principal intermediate cities served were Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore. Later, as Europe reeled from the carnage of World War I and connotations of European royalty fell into disfavor, the B&O discreetly omitted the sobriquet Royal Blue Line from its New York passenger service and the Royal Blue disappeared from B&O timetables. Beginning in 1917, former Royal Blue Line trains were renamed: the Royal Limited (inaugurated on May 15, 1898), for example, became the National Limited, continuing west from Washington to St. Louis via Cincinnati. During the Depression, the B&O hearkened back to the halcyon pre-World War I era when it launched a re-christened Royal Blue train between New York and Washington in 1935. The B&O finally discontinued passenger service north of Baltimore on April 26, 1958, and the Royal Blue faded into history.

Railroad historian Herbert Harwood said, in his seminal history of the service, "First conceived in late Victorian times to promote a new railroad line ... it was indeed one of the most memorable images in the transportation business, an inspired blend of majesty and mystique ... Royal Blue Line ... Royal Blue Trains ... the Royal Blue all meant different things at different times. But essentially they all symbolized one thing: the B&O's regal route."[1][2] Between the 1890s and World War I, the B&O's six daily Royal Blue trains providing service between New York and Washington were noted for their luxury, elegant appearance, and speed. The car interiors were paneled in mahogany, had fully enclosed vestibules (instead of open platforms, still widely in use at the time on U.S. railroads), then-modern heating and lighting, and leaded glass windows. The car exteriors were painted a deep "Royal Saxony blue" color with gold leaf trim.[3]

The B&O's use of electrification instead of steam power in a Baltimore tunnel on the Royal Blue Line, beginning in 1895, marked the first use of electric locomotives by an American railroad and presaged the dawn of practical alternatives to steam power in the 20th century.[4] Spurred by intense competition from the formidable Pennsylvania Railroad, the dominant railroad in the lucrative New York–Washington market since the 1880s, the Royal Blue in its mid-1930s reincarnation was noted for a number of technological innovations, including streamlining and the first non-articulated diesel locomotive on a passenger train in the U.S., a harbinger of the steam locomotive's eventual demise.[5]

History

1880s–1918

.jpg)

.jpg)

Prior to 1884, the B&O and the Philadelphia-based Pennsylvania Railroad both used the independent Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad (PW&B) between Baltimore, Maryland, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for their New York–Washington freight and passenger trains. In 1881, the Pennsylvania Railroad purchased a controlling interest in the PW&B, and in 1884 it denied the B&O further use of the PW&B to reach Philadelphia.

The B&O then built a new line from Baltimore to connect to the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad in Philadelphia, completed in 1886.[2] The B&O's passenger trains then used the Reading's New York Branch northward from Philadelphia to Bound Brook, New Jersey, where the Jersey Central's rails were used to reach the Communipaw Terminal in Jersey City. From Communipaw passengers connected to ferries for a twelve-minute crossing of the Hudson River to either Liberty Street Ferry Terminal or Whitehall Terminal in lower Manhattan.[3][6]

The new route presented problems in Baltimore, because a ferry boat was necessary to cross the harbor between Locust Point and Canton to connect with the B&O's Washington Branch.[3] The solution was the Baltimore Belt Line, which included a 1.4-mile (2.3 km) long tunnel under Howard Street in downtown Baltimore.[7] Work began on the tunnel in 1891 and was completed on May 1, 1895, when the first train traversed the tunnel. To avoid smoke problems from steam engines working upgrade in the long tunnel under the middle of Baltimore, the B&O pioneered the first mainline electrification of a U.S. railroad, installing an overhead third rail system in the tunnel and its approaches.[3][8] An electric locomotive first pulled a Royal Blue train through the Howard Street tunnel on June 27, 1895.[4]

.jpg)

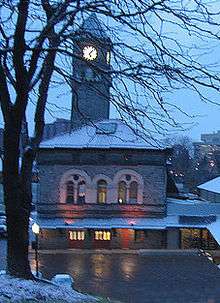

The project also included the construction of B&O's second passenger terminal in Baltimore, Mount Royal Station, at the north end of the Howard Street tunnel in the fashionable Bolton Hill neighborhood. Designed by Baltimore architect E. Francis Baldwin in a blend of modified Romanesque and Renaissance styling, the station was built of Maryland granite trimmed with Indiana limestone, with a red tile roof and landmark 150-foot (46 m) clocktower. The station's interior featured marble mosaic flooring, a fireplace, and rocking chairs. It opened the following year on September 1, 1896.[9] "It was considered," said the Baltimore Sun, "the most splendid station in the country built and used by only one railroad."[10] That evaluation was shared by railroad historian Lucius Beebe, who proclaimed Mount Royal "one of the celebrated railroad stations of the world, ranking in renown with Euston Station, London, scene of so many of Sherlock Holmes' departures, the Gare du Nord in Paris, and the feudal fortress of the Pennsylvania [Railroad] at Broad Street, Philadelphia".[11]

Even before the Baltimore Belt Line project was finished, the B&O launched its Royal Blue service on July 31, 1890. Powered by 4-6-0 steam locomotives having exceptionally large 78-inch (198 cm) diameter driving wheels for speed, the Royal Blue trains occasionally reached 90 mph (145 km/h). After the Baltimore Belt Line project was completed, travel time between New York and Washington was reduced to five hours, compared to nine hours in the late 1860s.[12][13]

The trains were noted for their elegance and luxury. The parlor cars' ceilings and upholstery were covered in royal blue, and the dining cars Queen and Waldorf, panelled in mahogany, featured elaborate cuisine such as terrapin and canvasback prepared by French-trained chefs.[14] A Railway Age magazine article of the time reporting on the Royal Blue called it "the climax in railway car building".[15]

1918–1920s

As a result of the U.S. entry into World War I and resulting congestion on the nation's railroads, the wartime U.S. Railroad Administration (USRA) ordered the Pennsylvania Railroad to permit B&O passenger trains to use its Hudson River tunnels and Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan, beginning April 28, 1918, eliminating the B&O's need for the ferry connection from Jersey City.[16] Following the end of World War I, the Pennsylvania Railroad continued to allow B&O passenger trains to use Pennsylvania Station for another eight years. On September 1, 1926, the Pennsylvania Railroad terminated its contract with the B&O, and the latter's trains reverted to the use of the Jersey Central's Jersey City terminal.[16] Passengers were then transferred to buses that met the train right on the platform. These buses were ferried across the Hudson River into Manhattan and Brooklyn, where they proceeded to various "stations" around the city on four different routes, including the Vanderbilt Hotel, Wanamaker's, Columbus Circle, and Rockefeller Center.[17] B&O's busiest Royal Blue bus terminal at 42nd street in Manhattan opened on December 17, 1928. Connected to Grand Central Terminal by an underground concourse, it was trimmed in marble and furnished with Art Deco lighting fixtures and leather sofas.[18] This arrangement would continue until the eventual demise of the Royal Blue in 1958.

1930s–1940s

As the 1930s dawned, the B&O's New York passenger service faced two significant competitive disadvantages, compared to the Pennsylvania Railroad. First, the B&O lacked direct access to Manhattan, resulting in slower overall travel time. Second, the Pennsylvania's move in the early 1930s to replace steam power with modern, smokeless electric service along its entire New York–Washington mainline was met with enthusiastic public approval.[2] The B&O responded by introducing Diesel locomotives, air conditioning, and streamlining on its New York trains. On June 24, 1935, the B&O inaugurated the first lightweight, streamlined train in the eastern U.S., when it began operating a re-christened Royal Blue train between Washington and New York.[19] When the specially modified 4-4-4-type steam locomotive prepared for the run proved less than satisfactory in terms of stability at speed, a new EMC 1800 hp B-B diesel-electric engine with a carbody by General Electric and mechanicals by Electro-Motive Corporation and numbered 50 replaced it, which was yet another first east of the Mississippi River. In 1937 this was replaced with the more demurely streamlined locomotive # 51 and booster 51x, among the first of the new E-Series road Diesel locomotives from General Motors' Electro Motive Company.[5][20] Previously, early experiments with internal combustion engines to replace steam in railroad applications included short, articulated trainsets (such as Burlington's Pioneer Zephyr and Union Pacific's M-10000), double-head sets of "boxcab" locomotives (developed by EMC) used to power the 1936 version of the AT&SF (Santa Fe) Super Chief (similar to number 50), and the cab/booster unit combinations developed with Union Pacific's M-10002 and M-10003 - M-10006 trainsets.[21] The E units took the most advanced developments of Diesel locomotive technology and made them available to all operators using the consists of their choice, and allowed Number 50 and the aluminum trainset to migrate west to subsidiary Alton, where it operated as the Abraham Lincoln. The earliest adopters of the new E units demonstrated the improved flexibility, efficiency and reduced maintenance costs of Diesel power in daily service compared to steam and gave impetus to the Dieselization of the railroad industry.[22][23]

Recalling the past glamor of the 1890s Royal Blue Line, the B&O introduced its Martha Washington-series dining cars, which were particularly noted for their fresh Chesapeake Bay cuisine, served on Dresden china in ornate cars with glass chandeliers and colonial-style furnishings.[24] The B&O's manager of dining car services said his department's objective was "...to be hospitable to our patrons in all respects – to make them feel the comfort, convenience and homelike atmosphere of our accommodations as soon as they step on our trains."[3] Dining car specialties included oysters and Chesapeake Bay fish served with cornmeal muffins. B&O president Daniel Willard personally sampled his dining cars' cuisine while traveling about the line, and recognized particularly pleasing meals with letters of appreciation and autographed pictures given to the dining car chefs.[14]

The B&O was not entirely satisfied with the ride quality of the lightweight Royal Blue train, however, and replaced it on April 25, 1937, with streamlined, refurbished heavyweight equipment, painted light gray and royal blue with gold striping, designed by Otto Kuhler. The B&O conveyed the displaced trainset to the Alton Railroad, where it ran as the Abraham Lincoln for decades.[25] The train was pulled by the streamlined Diesel locomotive, B&O # 51, of the 3,600 h.p. EMC EA/EB model built by Electro Motive Company. Praised for its beauty and handsome profile, this first streamlined production model Diesel "dazzled the press and public", said one magazine writer of the groundbreaking locomotive's introduction.[5][20] Kuhler also streamlined one of B&O's 4-6-2 "Pacific" steam locomotives for use on the Royal Blue.[26] Its bullet-shaped shroud became an iconic image for the Royal Blue and was modeled for years by American Flyer. Time magazine, in reporting on the precarious financial condition of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and other Depression-ravaged rail lines in 1937, referred to the B&O's "swashbuckling" Royal Blue streamliner launched that year as having "symbolize[d] the new era in railroading ..."[27]

President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt was a frequent passenger on the B&O's Royal Blue Line during his time in office (1933–1945), when he traveled between Washington and his family home in Hyde Park, New York. A special presidential train from Washington used the regular B&O–Reading–Jersey Central route to Jersey City, continuing on the New York Central Railroad's West Shore Line along the Hudson River to Highland, New York (opposite Poughkeepsie), where the President was met by automobile.[22]

Along with most other rail passenger services in the U.S. during World War II, the Royal Blue enjoyed a surge in passenger traffic between 1942 and 1945 as volume doubled to 1.2 million passengers annually on B&O's eight daily New York–Washington trains.[28] Following the end of the war, however, passenger volumes soon dropped below prewar levels and the B&O discontinued one of its daily New York–Washington trains. In addition to its flagship Royal Blue, six other B&O passenger trains continued to serve New York until April 1958: the Metropolitan Special, Capitol Limited, National Limited, Diplomat, Marylander, and Shenandoah.[29]

1950s and the end

Although all of B&O's Washington–Jersey City passenger trains had been fully dieselized by September 28, 1947, no new passenger cars were built for the Royal Blue in the postwar period. The refurbished 8-car 1937 Royal Blue trainset continued in operation to the end. The overwhelming market dominance of the Pennsylvania Railroad was evident when it introduced the 18-car stainless steel Morning Congressional and Afternoon Congressional streamliners in 1952.[30] By the late 1950s, most U.S. passenger trains suffered a steep decline in patronage as the traveling public abandoned trains in favor of airplanes and automobiles, utilizing improved Interstate Highways. The Royal Blue was no exception, as operating deficits approached $5 million annually and passenger volume declined by almost half between 1946 and 1957.[2][31] Amidst the downward trend, the Royal Blue Line briefly recaptured the regal splendor of its early years on October 21, 1957, when Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip travelled on the B&O from Washington to New York.[32]

As financial losses mounted, the B&O finally ceded the New York–Washington market to the Pennsylvania Railroad altogether, discontinuing all passenger service north of Baltimore on Saturday, April 26, 1958, and bringing the venerable Royal Blue to an end.[33] As the engineer was about to ease the locomotive's throttle open for the Royal Blue's final departure from Washington Union Station at 3:45 p.m., the event was covered in a trainside remote broadcast by Edward R. Murrow on a CBS network See It Now television special.[34] The train's 7:49 p.m. arrival at Jersey City Terminal was met by news reporters from The New York Times, the New York Post, Life magazine and The Saturday Evening Post, on hand to cover the legendary Royal Blue's demise.[31] In an editorial the next day, the Baltimore Sun lamented the end of the Royal Blue, saying it "may have been one of the most famous named trains in history".[31]

The New York Times, in a front page article accompanied by a photograph of train engineer Michael Goodnight bidding farewell to a 7-year old passenger, said "It was a sad and simple story yesterday as the nation's oldest railroad discontinued its crack Royal Blue and its five other passenger trains ... end[ing] sixty-eight years of continuous through service, operated in a gentlemanly fashion ... a kind of ante-bellum, gracious way of life ... and the reputation for very special service."[35]

Mount Royal Station continued as the eastern terminus of B&O's passenger service until June 30, 1961, when it closed permanently as a rail passenger facility.[10] It was one of thirteen Baltimore buildings selected in 1959 for the Historic American Buildings Survey.[10] The building and trainshed were subsequently acquired by the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in 1964 and are preserved as examples of late 19th century industrial architecture.[36]

Schedule and equipment

In the 1890s–1910s period, the Royal Limited operated in both directions simultaneously, with 3 p.m. departures in New York and Washington, arriving at its destination five hours later, at 8 p.m. By the 1930s, travel time between Jersey City and Washington was reduced to four hours.[37] From 1935 to the end of service in 1958, the Royal Blue made a daily round trip, departing New York in the morning and returning from Washington in the evening. According to the Official Guide of February, 1956, the Royal Blue operated on the following schedule as train #27 (unconditional stops highlighted in blue, bus connections in yellow):

| City | Departure time |

|---|---|

| New York (Rockefeller Center) | 8:30 am |

| New York (Grand Central Terminal) | 8:45 am |

| Brooklyn, NY | 8:45 am |

| Jersey City, NJ | 9:30 am |

| Elizabeth, NJ | 9:46 am |

| Plainfield, NJ | 9:59 am |

| Wayne Junction, Pa. | 10:54 am |

| Philadelphia, Pa. | 11:10 am |

| Wilmington, Del. | 11:35 am |

| Baltimore, Md. (Mt. Royal Station) | 12:38 pm |

| Baltimore, Md. (Camden Station) | 12:45 pm |

| Washington, D.C. (Union Station) | 1:30 pm |

| Source: Official Guide of the Railways, p. 418[29] | |

Eastbound, the train departed Washington at 3:45 p.m. as train # 28, arriving at Jersey City 7:40 p.m.

Between 1937 and 1958, the Royal Blue was equipped with air-conditioned coaches, parlor cars with private drawing rooms, a lounge car for coach passengers, a full dining car serving complete meals, and a flat-end observation car with a "cafe-lounge" bringing up the rear of the train.[25][29] Beginning in mid-August 1947, onboard telephone service was provided, making the B&O (along with the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central Railroad) one of the first three railroads in the U.S. to offer telephone service on its trains, using a forerunner of cell phone technology.[29][38]

In popular culture

In 1891, M. Beerhalter of Philadelphia published "The Royal Blue Line March" composed by Adam Geibel.

See also

- B&O Railroad Museum (Baltimore), where selected equipment, diner china and silverware, and other artifacts from various Royal Blue trains are exhibited.

References

- ↑ Herbert H. Harwood, Jr., Royal Blue Line. Sykesville, Md.: Greenberg Publishing, 1990 (ISBN 0-89778-155-4), p. ix.

- 1 2 3 4 Morgan, David P. (August 1958). "Royal Blue Line 1890—1958". Trains magazine. Kalmbach Publishing. 18 (8).

- 1 2 3 4 5 John F. Stover, History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, 1987 (ISBN 0-911198-81-4), pp. 172–176.

- 1 2 F.G. Bennick, "B&O was first U.S. railroad to use electric locomotives", B&O Magazine, April, 1940, pp. 19–23.

- 1 2 3 Harwood, Royal Blue Line, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Railroad Ferries of the Hudson: And Stories of a Deckhand, by, Raymond J. Baxter, Arthur G. Adams, pg. 55 ,1999, Fordham University Press, 978-0823219544

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 86. In the mid-1980s, the tunnel's original length of 1.4 miles or 7,340 feet (2,237 m) was extended an additional three-tenths of a mile (480 m) further south of its original Camden Station portal when the B&O successor CSX Transportation's mainline track east of the B&O warehouse was covered over for construction of Interstate 395 (ref: Stephen J. Salamon, David P. Oroszi, and David P. Ori, Baltimore and Ohio – Reflections of the Capitol Dome. Silver Spring, Md.: Old Line Graphics, 1993 (ISBN 1-879314-08-8), pp. 26–28).

- ↑ Timothy Jacobs, The History of the Baltimore & Ohio. New York: Crescent Books, 1989 (ISBN 0-517-67603-6), p. 68.

- ↑ Stephen J. Salamon, David P. Oroszi, and David P. Ori, Baltimore and Ohio – Reflections of the Capitol Dome. Silver Spring, Md.: Old Line Graphics, 1993 (ISBN 1-879314-08-8), p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Charles V. Flowers, "Mount Royal Closes Doors But Tower Clock Will Run", The Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1961.

- ↑ Beebe, Lucius & Clegg, Charles (1993). The Trains We Rode. New York: Promontory Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-88394-081-7.

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 114.

- ↑ Official Guide of the Railways. New York: National Railway Publication Co., June 1868, p. 138.

- 1 2 Stover, p. 228.

- ↑ Railway Age article from 1895, as quoted in "Royal Blue Line's Diners Were Elaborate Examples of Gay Nineties' Styling", Baltimore & Ohio Magazine, April, 1940.

- 1 2 Harwood, Royal Blue Line, pp. 118–127.

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, pp. 118–127, 150.

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 127.

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 142.

- 1 2 David P. Morgan (May 1964). "Those esthetic E's". Trains magazine: 20–23.

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 139.

- 1 2 Herbert W. Harwood, Jr., Impossible Challenge. Baltimore, Md.: Bernard, Roberts and Co., 1979 (ISBN 0-934118-17-5), pp. 252–254.

- ↑ Jacobs, p. 104.

- ↑ Kratville, William W. (1962). Steam Steel and Limiteds. A Saga of the Great Varnish Era. Omaha, NE: Barnhart Press. p. 168. OCLC 1301983.

- 1 2 Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 145.

- ↑ Kratville, p. 92.

- ↑ "Royal Blue's Blues". Time magazine. January 10, 1938. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 160.

- 1 2 3 4 Official Guide of the Railways. New York: National Railway Publication Co., February 1956, pp. 414–418.

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 163.

- 1 2 3 Frederick N. Rasmussen (April 27, 2008). "Lonesome whistle blew for last time". The Baltimore Sun. p. 21A. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Railroad News Photos". Trains magazine. 18 (4): 8. February 1958.

- ↑ Salamon, Oroszi & Ori, p. 9.

- ↑ Greco, Tom (2008). "A Last Ride on the Royal Blue". The Sentinel. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Historical Society. 30 (2): 17. ISSN 1053-4415. OCLC 15367925.

- ↑ Philip Benjamin (April 27, 1958). "The Royal Blue and 5 Other Trains Give In to Economics" (PDF). The New York Times. pp. 1, 41. Retrieved March 12, 2009.

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 171.

- ↑ Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 161.

- ↑ Bert Pennypacker, "Dial direct at 110 mph", Trains, April, 1968.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal Blue (train). |