Endoplasmic reticulum

| Cell biology | |

|---|---|

| The animal cell | |

|

Components of a typical animal cell:

|

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a type of organelle in eukaryotic cells that forms an interconnected network of flattened, membrane-enclosed sacs or tube-like structures known as cisternae. The membranes of the ER are continuous with the outer nuclear membrane. The endoplasmic reticulum occurs in most types of eukaryotic cells, but is absent from red blood cells and spermatozoa. There are two types of endoplasmic reticulum: rough and smooth. The outer (cytosolic) face of the rough endoplasmic reticulum is studded with ribosomes that are the sites of protein synthesis. The rough endoplasmic reticulum is especially prominent in cells such as hepatocytes. The smooth endoplasmic reticulum lacks ribosomes and functions in lipid manufacture and metabolism, the production of steroid hormones, and detoxification.[1] The smooth ER is especially abundant in mammalian liver and gonad cells. The lacy membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum were first seen in 1945 using electron microscopy.

History

The lacy membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum were first seen in 1945 by Keith R. Porter, Albert Claude, Brody Meskers and Ernest F. Fullam, using electron microscopy.[2] The word reticulum, which means "network", was applied to describe this fabric of membranes.

Structure

The general structure of the endoplasmic reticulum is a network of membranes called cisternae. These sac-like structures are held together by the cytoskeleton. The phospholipid membrane encloses the cisternal space (or lumen), which is continuous with the perinuclear space but separate from the cytosol. The functions of the endoplasmic reticulum can be summarized as the synthesis and export of proteins and membrane lipids, but varies between ER and cell type and cell function. The quantity of both rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum in a cell can slowly interchange from one type to the other, depending on the changing metabolic activities of the cell. Transformation can include embedding of new proteins in membrane as well as structural changes. Changes in protein content may occur without noticeable structural changes.[3][4]

Rough endoplasmic reticulum

The surface of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (often abbreviated RER or Rough ER) (also called granular endoplasmic reticulum) is studded with protein-manufacturing ribosomes giving it a "rough" appearance (hence its name).[5] The binding site of the ribosome on the rough endoplasmic reticulum is the translocon.[6] However, the ribosomes are not a stable part of this organelle's structure as they are constantly being bound and released from the membrane. A ribosome only binds to the RER once a specific protein-nucleic acid complex forms in the cytosol. This special complex forms when a free ribosome begins translating the mRNA of a protein destined for the secretory pathway.[7] The first 5–30 amino acids polymerized encode a signal peptide, a molecular message that is recognized and bound by a signal recognition particle (SRP). Translation pauses and the ribosome complex binds to the RER translocon where translation continues with the nascent (new) protein forming into the RER lumen and/or membrane. The protein is processed in the ER lumen by an enzyme (a signal peptidase), which removes the signal peptide. Ribosomes at this point may be released back into the cytosol; however, non-translating ribosomes are also known to stay associated with translocons.[8]

The membrane of the rough endoplasmic reticulum forms large double membrane sheets that are located near, and continuous with, the outer layer of the nuclear envelope.[9] The double membrane sheets are stacked and connected through several right or left-handed helical ramps, the so-called Terasaki ramps, giving rise to a structure resembling a parking garage.[10] Although there is no continuous membrane between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus, membrane-bound vesicles shuttle proteins between these two compartments.[11] Vesicles are surrounded by coating proteins called COPI and COPII. COPII targets vesicles to the Golgi apparatus and COPI marks them to be brought back to the rough endoplasmic reticulum. The rough endoplasmic reticulum works in concert with the Golgi complex to target new proteins to their proper destinations. A second method of transport out of the endoplasmic reticulum involves areas called membrane contact sites, where the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and other organelles are held closely together, allowing the transfer of lipids and other small molecules.[12][13]

The rough endoplasmic reticulum is key in multiple functions:

- Manufacture of lysosomal enzymes with a mannose-6-phosphate marker added in the cis-Golgi network

- Manufacture of secreted proteins, either secreted constitutively with no tag or secreted in a regulatory manner involving clathrin and paired basic amino acids in the signal peptide.

- Integral membrane proteins that stay embedded in the membrane as vesicles exit and bind to new membranes. Rab proteins are key in targeting the membrane; SNAP and SNARE proteins are key in the fusion event.

- Initial glycosylation as assembly continues. This is N-linked (O-linking occurs in the Golgi).

Smooth endoplasmic reticulum

In most cells the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (abbreviated SER) is scarce. Instead there are areas where the ER is partly smooth and partly rough, this area is called the transitional ER. The transitional ER gets its name because it contains ER exit sites. These are areas where the transport vesicles that contain lipids and proteins made in the ER, detach from the ER and start moving to the Golgi apparatus. Specialized cells can have a lot of smooth endoplasmic reticulum and in these cells the smooth ER has many functions.[14] It synthesizes lipids, phospholipids, and steroids. Cells which secrete these products, such as those in the testes, ovaries, and sebaceous glands have an abundance of smooth endoplasmic reticulum.[15] It also carries out the metabolism of carbohydrates, detoxification of natural metabolism products and of alcohol and drugs, attachment of receptors on cell membrane proteins, and steroid metabolism.[16] In muscle cells, it regulates calcium ion concentration. Smooth endoplasmic reticulum is found in a variety of cell types (both animal and plant), and it serves different functions in each. The smooth endoplasmic reticulum also contains the enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase, which converts glucose-6-phosphate to glucose, a step in gluconeogenesis. It is connected to the nuclear envelope and consists of tubules that are located near the cell periphery. These tubes sometimes branch forming a network that is reticular in appearance.[9] In some cells, there are dilated areas like the sacs of rough endoplasmic reticulum. The network of smooth endoplasmic reticulum allows for an increased surface area to be devoted to the action or storage of key enzymes and the products of these enzymes.

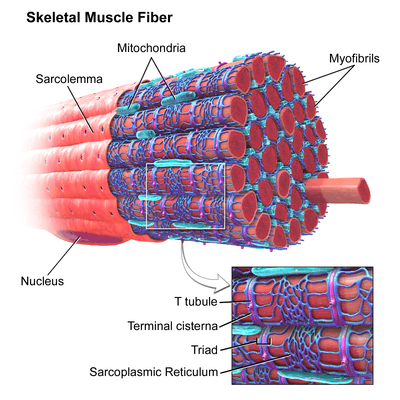

Sarcoplasmic reticulum

The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), from the Greek σάρξ sarx ("flesh"), is smooth ER found in myocytes. The only structural difference between this organelle and the smooth endoplasmic reticulum is the medley of proteins they have, both bound to their membranes and drifting within the confines of their lumens. This fundamental difference is indicative of their functions: The endoplasmic reticulum synthesizes molecules, while the sarcoplasmic reticulum stores calcium ions and pumps them out into the sarcoplasm when the muscle fiber is stimulated.[17][18] After their release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, calcium ions interact with contractile proteins that utilize ATP to shorten the muscle fiber. The sarcoplasmic reticulum plays a major role in excitation-contraction coupling.[19]

Functions

The endoplasmic reticulum serves many general functions, including the folding of protein molecules in sacs called cisternae and the transport of synthesized proteins in vesicles to the Golgi apparatus. Correct folding of newly made proteins is made possible by several endoplasmic reticulum chaperone proteins, including protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), ERp29, the Hsp70 family member BiP/Grp78, calnexin, calreticulin, and the peptidylpropyl isomerase family. Only properly folded proteins are transported from the rough ER to the Golgi apparatus – unfolded proteins cause an unfolded protein response as a stress response in the ER. Disturbances in redox regulation, calcium regulation, glucose deprivation, and viral infection[20] or the over-expression of proteins[21] can lead to endoplasmic reticulum stress response (ER stress), a state in which the folding of proteins slows, leading to an increase in unfolded proteins. This stress is emerging as a potential cause of damage in hypoxia/ischemia, insulin resistance, and other disorders.[22]

Protein transport

Secretory proteins, mostly glycoproteins, are moved across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Proteins that are transported by the endoplasmic reticulum throughout the cell are marked with an address tag called a signal sequence. The N-terminus (one end) of a polypeptide chain (i.e., a protein) contains a few amino acids that work as an address tag, which are removed when the polypeptide reaches its destination. Nascent peptides reach the ER via the translocon, a membrane-embedded multiprotein complex. Proteins that are destined for places outside the endoplasmic reticulum are packed into transport vesicles and moved along the cytoskeleton toward their destination. In human fibroblasts, the ER is always co-distributed with microtubules and the depolymerisation of the latter cause its co-aggregation with mitochondria, which are also associated with the ER.[23]

The endoplasmic reticulum is also part of a protein sorting pathway. It is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell. The majority of its resident proteins are retained within it through a retention motif. This motif is composed of four amino acids at the end of the protein sequence. The most common retention sequences are KDEL for lumen located proteins and KKXX for transmembrane protein.[24] However, variations of KDEL and KKXX do occur, and other sequences can also give rise to endoplasmic reticulum retention. It is not known whether such variation can lead to sub-ER localizations. There are three KDEL (1, 2 and 3) receptors in mammalian cells, and they have a very high degree of sequence identity. The functional differences between these receptors remain to be established.[25]

Clinical significance

Abnormalities in XBP1 lead to a heightened endoplasmic reticulum stress response and subsequently causes a higher susceptibility for inflammatory processes that may even contribute to Alzheimer's disease.[26] In the colon, XBP1 anomalies have been linked to the inflammatory bowel diseases including Crohn's disease.[27]

The unfolded protein response (UPR) is a cellular stress response related to the endoplasmic reticulum.[28] The UPR is activated in response to an accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. The UPR functions to restore normal function of the cell by halting protein translation, degrading misfolded proteins, and activating the signaling pathways that lead to increasing the production of molecular chaperones involved in protein folding. Sustained overactivation of the UPR has been implicated in prion diseases as well as several other neurodegenerative diseases and the inhibition of the UPR could become a treatment for those diseases.[29]

References

- ↑ "Endoplasmic Reticulum (Rough and Smooth)". Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Porter KR, Claude A, Fullam EF (March 1945). "A study of tissue culture cells by electron microscopy". J Exp Med. 81 (3): 233–246. PMC 2135493

. PMID 19871454. doi:10.1084/jem.81.3.233.

. PMID 19871454. doi:10.1084/jem.81.3.233. - ↑ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

- ↑ Cooper, Geoffrey M. (2000). The cell : a molecular approach (2nd ed.). Washington (DC): ASM Press. ISBN 0-87893-106-6.

- ↑ "reticulum". The Free Dictionary.

- ↑ Görlich D, Prehn S, Hartmann E, Kalies KU, Rapoport TA (Oct 1992). "A mammalian homolog of SEC61p and SECYp is associated with ribosomes and nascent polypeptides during translocation.". Cell. 71 (3): 489–503. PMID 1423609. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90517-G.

- ↑ Lodish, Harvey; et al. (2003). Molecular Cell Biology (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. pp. 659–666. ISBN 0-7167-4366-3.

- ↑ Seiser, R. M. (2000). "The Fate of Membrane-bound Ribosomes Following the Termination of Protein Synthesis". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (43): 33820–33827. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 10931837. doi:10.1074/jbc.M004462200.

- 1 2 Shibata, Yoko; Voeltz, Gia K.; Rapoport, Tom A. (2006). "Rough Sheets and Smooth Tubules". Cell. 126 (3): 435–439. ISSN 0092-8674. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.019.

- ↑ Terasaki, Mark; Shemesh, Tom; Kasthuri, Narayanan; Klemm, Robin W.; Schalek, Richard; Hayworth, Kenneth J.; Hand, Arthur R.; Yankova, Maya; Huber, Greg; Lichtman, Jeff W.; Rapoport, Tom A.; Kozlov, Michael M. (2013). "Stacked Endoplasmic Reticulum Sheets Are Connected by Helicoidal Membrane Motifs". Cell. 154 (2): 285–296. PMC 3767119

. PMID 23870120. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.031.

. PMID 23870120. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.031. - ↑ Endoplasmic reticulum. (n.d.). McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology. Retrieved September 13, 2006, from Answers.com Web site: http://www.answers.com/topic/endoplasmic-reticulum

- ↑ Levine T (September 2004). "Short-range intracellular trafficking of small molecules across endoplasmic reticulum junctions". Trends Cell Biol. 14 (9): 483–90. PMID 15350976. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.017.

- ↑ Levine T, Loewen C (August 2006). "Inter-organelle membrane contact sites: through a glass, darkly". Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18 (4): 371–8. PMID 16806880. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.011.

- ↑ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin Peter Walter.; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed. ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

- ↑ "Functions of Smooth ER". University of Minnesota Duluth.

- ↑ Maxfield FR, Wüstner D (October 2002). "Intracellular cholesterol transport". J. Clin. Invest. 110 (7): 891–8. PMC 151159

. PMID 12370264. doi:10.1172/JCI16500.

. PMID 12370264. doi:10.1172/JCI16500. - ↑ Toyoshima C, Nakasako M, Nomura H, Ogawa H (2000). "Crystal structure of the calcium pump of sarcoplasmic reticulum at 2.6 A resolution". Nature. 405 (6787): 647–55. PMID 10864315. doi:10.1038/35015017.

- ↑ Medical Cell Biology 3rd/ed. Academic Press. p. 69.

- ↑ Martini, Frederick; Nath, Judi; Bartholomew, Edwin (2014). Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology (10th ed.). ISBN 978-0321909077.

- ↑ Xu, C; et al. (2005). "Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress: Cell Life and Death Decisions". J. Clin. Invest. 115 (10): 2656–2664. PMC 1236697

. PMID 16200199. doi:10.1172/JCI26373.

. PMID 16200199. doi:10.1172/JCI26373. - ↑ Kober L, Zehe C, Bode J (October 2012). "Development of a novel ER stress based selection system for the isolation of highly productive clones". Biotechnol. Bioeng. 109 (10): 2599–611. PMID 22510960. doi:10.1002/bit.24527.

- ↑ Ozcan, U.; Cao, Q; Yilmaz, E; Lee, AH; Iwakoshi, NN; Ozdelen, E; Tuncman, G; Görgün, C; Glimcher, LH; Hotamisligil, GS (2004). "Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes". Science. 306 (5695): 457–461. PMID 15486293. doi:10.1126/science.1103160.

- ↑ Soltys, BJ; Gupta, RS. "Interrelationships of endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, intermediate filaments, and microtubules—a quadruple fluorescence labeling study". Biochem Cell Biol. 70 (10–11): 1174–86. PMID 1363623. doi:10.1139/o92-163.

- ↑ Mariano Stornaiuolo; Lavinia V. Lotti; Nica Borgese; Maria-Rosaria Torrisi; Giovanna Mottola; Gianluca Martire; Stefano Bonatti (March 2003). "KDEL and KKXX Retrieval Signals Appended to the Same Reporter Protein Determine Different Trafficking between Endoplasmic Reticulum, Intermediate Compartment, and Golgi Complex". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 14 (3): 889–902. PMC 151567

. PMID 12631711. doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0468.

. PMID 12631711. doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0468. - ↑ Raykhel, I; Alanen, H; Salo, K; Jurvansuu, J; Nguyen, VD; Latva-Ranta, M; Ruddock, L (2007). "A molecular specificity code for the three mammalian KDEL receptors". J. Cell Biol. 179 (6): 1193–204. PMC 2140024

. PMID 18086916. doi:10.1083/jcb.200705180.

. PMID 18086916. doi:10.1083/jcb.200705180. - ↑ Casas-Tinto, S; Zhang, Y; Sanchez-Garcia, J; Gomez-Velazquez, M; Rincon-Limas, DE; Fernandez-Funez, P (25 March 2011). "The ER stress factor XBP1s prevents amyloid-{beta} neurotoxicity.". Human Molecular Genetics. 20 (11): 2144–60. PMC 3090193

. PMID 21389082. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddr100.

. PMID 21389082. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddr100. - ↑ Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, Glickman JN, Zeissig S, Tilg H, Nieuwenhuis EE, Higgins DE, Schreiber S, Glimcher LH, Blumberg RS (September 2008). "XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease". Cell. 134 (5): 743–56. PMC 2586148

. PMID 18775308. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021.

. PMID 18775308. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021. - ↑ Walter, Peter. "Peter Walter's short talk: Unfolding the UPR". iBiology.

- ↑ Moreno, J. A.; Halliday, M.; Molloy, C.; Radford, H.; Verity, N.; Axten, J. M.; Ortori, C. A.; Willis, A. E.; Fischer, P. M.; Barrett, D. A.; Mallucci, G. R. (2013). "Oral Treatment Targeting the Unfolded Protein Response Prevents Neurodegeneration and Clinical Disease in Prion-Infected Mice". Science Translational Medicine. 5 (206): 206ra138. PMID 24107777. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3006767.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Endoplasmic reticulum. |

- Lipid and protein composition of Endoplasmic reticulum in OPM database

- Animations of the various cell functions referenced here