Rotavirus

| Rotavirus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Computer–aided reconstruction of a rotavirus based on several electron micrographs | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group III (dsRNA) |

| Order: | Unassigned |

| Family: | Reoviridae |

| Subfamily: | Sedoreovirinae |

| Genus: | Rotavirus |

| Type species | |

| Rotavirus A | |

| Species | |

| |

Rotavirus is the most common cause of diarrhoeal disease among infants and young children.[1] It is a genus of double-stranded RNA viruses in the family Reoviridae. Nearly every child in the world is infected with rotavirus at least once by the age of five.[2] Immunity develops with each infection, so subsequent infections are less severe; adults are rarely affected.[3] There are eight species of this virus, referred to as A, B, C, D, E, F, G and H. Rotavirus A, the most common species, causes more than 90% of rotavirus infections in humans.

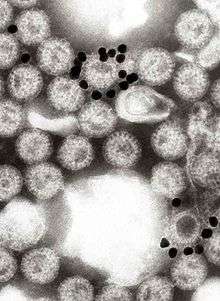

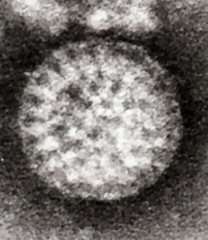

The virus is transmitted by the faecal-oral route. It infects and damages the cells that line the small intestine and causes gastroenteritis (which is often called "stomach flu" despite having no relation to influenza). Although rotavirus was discovered in 1973 by Ruth Bishop and her colleagues by electron micrograph images[4] and accounts for approximately one third of hospitalisations for severe diarrhoea in infants and children,[5] its importance has historically been underestimated within the public health community, particularly in developing countries.[6] In addition to its impact on human health, rotavirus also infects animals, and is a pathogen of livestock.[7]

Rotavirus is usually an easily managed disease of childhood, but in 2013, rotavirus caused 37 percent of deaths of children from diarrhoea and 215,000 deaths worldwide,[8] and almost two million more become severely ill.[6] Most of these deaths occurred in developing countries.[9] In the United States, before initiation of the rotavirus vaccination programme, rotavirus caused about 2.7 million cases of severe gastroenteritis in children, almost 60,000 hospitalisations, and around 37 deaths each year.[10] Following rotavirus vaccine introduction in the United States, hospitalisation rates have fallen significantly.[11][12] Public health campaigns to combat rotavirus focus on providing oral rehydration therapy for infected children and vaccination to prevent the disease.[13] The incidence and severity of rotavirus infections has declined significantly in countries that have added rotavirus vaccine to their routine childhood immunisation policies.[14][15][16]

Signs and symptoms

Rotaviral enteritis is a mild to severe disease characterised by nausea, vomiting, watery diarrhoea and low-grade fever. Once a child is infected by the virus, there is an incubation period of about two days before symptoms appear.[17] The period of illness is acute. Symptoms often start with vomiting followed by four to eight days of profuse diarrhoea. Dehydration is more common in rotavirus infection than in most of those caused by bacterial pathogens, and is the most common cause of death related to rotavirus infection.[18]

Rotavirus A infections can occur throughout life: the first usually produces symptoms, but subsequent infections are typically mild or asymptomatic,[19][20] as the immune system provides some protection.[21][22] Consequently, symptomatic infection rates are highest in children under two years of age and decrease progressively towards 45 years of age.[23] Infection in newborn children, although common, is often associated with mild or asymptomatic disease;[3] the most severe symptoms tend to occur in children six months to two years of age, the elderly, and those with immunodeficiency. Due to immunity acquired in childhood, most adults are not susceptible to rotavirus; gastroenteritis in adults usually has a cause other than rotavirus, but asymptomatic infections in adults may maintain the transmission of infection in the community.[24]

Virology

There are eight species of rotavirus, referred to as A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H.[25] Humans are primarily infected by species A, B and C, most commonly by species A. A–E species cause disease in other animals,[26] species E and H in pigs, and D, F and G in birds.[27][28] Within rotavirus A there are different strains, called serotypes.[29] As with influenza virus, a dual classification system is used based on two proteins on the surface of the virus. The glycoprotein VP7 defines the G serotypes and the protease-sensitive protein VP4 defines P serotypes.[30] Because the two genes that determine G-types and P-types can be passed on separately to progeny viruses, different combinations are found.[31]

Structure

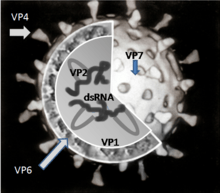

The genome of rotavirus consists of 11 unique double helix molecules of RNA which are 18,555 nucleotides in total. Each helix, or segment, is a gene, numbered 1 to 11 by decreasing size. Each gene codes for one protein, except genes 9, which codes for two.[23] The RNA is surrounded by a three-layered icosahedral protein capsid. Viral particles are up to 76.5 nm in diameter[32][33] and are not enveloped.

Proteins

There are six viral proteins (VPs) that form the virus particle (virion). These structural proteins are called VP1, VP2, VP3, VP4, VP6 and VP7. In addition to the VPs, there are six nonstructural proteins (NSPs), that are only produced in cells infected by rotavirus. These are called NSP1, NSP2, NSP3, NSP4, NSP5 and NSP6.[26]

At least six of the twelve proteins encoded by the rotavirus genome bind RNA.[34] The role of these proteins play in rotavirus replication is not entirely understood; their functions are thought to be related to RNA synthesis and packaging in the virion, mRNA transport to the site of genome replication, and mRNA translation and regulation of gene expression.[35]

Structural proteins

VP1 is located in the core of the virus particle and is an RNA polymerase enzyme.[36] In an infected cell this enzyme produces mRNA transcripts for the synthesis of viral proteins and produces copies of the rotavirus genome RNA segments for newly produced virus particles.

VP2 forms the core layer of the virion and binds the RNA genome.[37]

VP3 is part of the inner core of the virion and is an enzyme called guanylyl transferase. This is a capping enzyme that catalyses the formation of the 5' cap in the post-transcriptional modification of mRNA.[38] The cap stabilises viral mRNA by protecting it from nucleic acid degrading enzymes called nucleases.[39]

VP4 is on the surface of the virion that protrudes as a spike.[40] It binds to molecules on the surface of cells called receptors and drives the entry of the virus into the cell.[41] VP4 has to be modified by the protease enzyme trypsin, which is found in the gut, into VP5* and VP8* before the virus is infectious.[42] VP4 determines how virulent the virus is and it determines the P-type of the virus.[43]

VP6 forms the bulk of the capsid. It is highly antigenic and can be used to identify rotavirus species.[20] This protein is used in laboratory tests for rotavirus A infections.[44]

VP7 is a glycoprotein that forms the outer surface of the virion. Apart from its structural functions, it determines the G-type of the strain and, along with VP4, is involved in immunity to infection.[32]

Nonstructural viral proteins

NSP1, the product of gene 5, is a nonstructural RNA-binding protein.[45] NSP1 also blocks the interferon response, the part of the innate immune system that protects cells from viral infection. NSP1 causes the proteosome to degrade key signaling components required to stimulate production of interferon in an infected cell and to respond to interferon secreted by adjacent cells. Targets for degradation include several IRF transcription factors required for interferon gene transcription.[46]

NSP2 is an RNA-binding protein that accumulates in cytoplasmic inclusions (viroplasms) and is required for genome replication.[47][48]

NSP3 is bound to viral mRNAs in infected cells and it is responsible for the shutdown of cellular protein synthesis.[49] NSP3 inactivates two translation initiation factors essential for synthesis of proteins from host mRNA. First, NSP3 ejects poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) from the translation initiation factor eIF4F. PABP is required for efficient translation of transcripts with a 3' poly(A) tail, which is found on most host cell transcripts. Second, NSP3 inactivates eIF2 by stimulating its phosphorylation. Efficient translation of rotavirus mRNA, which lacks the 3' poly(A) tail, does not require either of these factors.[50]

NSP4 is a viral enterotoxin that induces diarrhoea and was the first viral enterotoxin discovered.[51]

NSP5 is encoded by genome segment 11 of rotavirus A. In virus-infected cells NSP5 accumulates in the viroplasm.[52]

NSP6 is a nucleic acid binding protein[53] and is encoded by gene 11 from an out-of-phase open reading frame.[54]

| RNA Segment (Gene) | Size (base pairs) | Protein | Molecular weight kDa | Location | Copies per particle | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3302 | VP1 | 125 | At the vertices of the core | <25 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

| 2 | 2690 | VP2 | 102 | Forms inner shell of the core | 120 | Stimulates viral RNA replicase |

| 3 | 2591 | VP3 | 88 | At the vertices of the core | <25 | methyltransferase mRNA capping enzyme |

| 4 | 2362 | VP4 | 87 | Surface spike | 120 | Cell attachment, virulence |

| 5 | 1611 | NSP1 | 59 | Nonstructural | 0 | 5'RNA binding, interferon antagonist |

| 6 | 1356 | VP6 | 45 | Inner Capsid | 780 | Structural and species-specific antigen |

| 7 | 1104 | NSP3 | 37 | Nonstructural | 0 | Enhances viral mRNA activity and shut-offs cellular protein synthesis |

| 8 | 1059 | NSP2 | 35 | Nonstructural | 0 | NTPase involved in RNA packaging |

| 9 | 1062 | VP71 VP72 | 38 and 34 | Surface | 780 | Structural and neutralisation antigen |

| 10 | 751 | NSP4 | 20 | Nonstructural | 0 | Enterotoxin |

| 11 | 667 | NSP5 NSP6 | 22 | Nonstructural | 0 | ssRNA and dsRNA binding modulator of NSP2, phosphoprotein |

This table is based on the simian rotavirus strain SA11.[55][56][57] RNA-protein coding assignments differ in some strains.

Replication

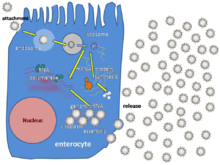

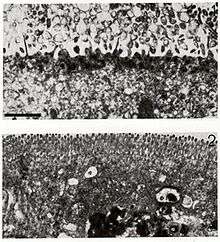

Rotaviruses replicate mainly in the gut,[58] and infect enterocytes of the villi of the small intestine, leading to structural and functional changes of the epithelium.[59] The triple protein coats make them resistant to the acidic pH of the stomach and the digestive enzymes in the gut.

The virus enter cells by receptor mediated endocytosis and form a vesicle known as an endosome. Proteins in the third layer (VP7 and the VP4 spike) disrupt the membrane of the endosome, creating a difference in the calcium concentration. This causes the breakdown of VP7 trimers into single protein subunits, leaving the VP2 and VP6 protein coats around the viral dsRNA, forming a double-layered particle (DLP).[60]

The eleven dsRNA strands remain within the protection of the two protein shells and the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase creates mRNA transcripts of the double-stranded viral genome. By remaining in the core, the viral RNA evades innate host immune responses called RNA interference that are triggered by the presence of double-stranded RNA.

During the infection, rotavirus produces mRNA for both protein biosynthesis and gene replication. Most of the rotavirus proteins accumulate in viroplasm, where the RNA is replicated and the DLPs are assembled. Viroplasm is formed around the cell nucleus as early as two hours after virus infection, and consists of viral factories thought to be made by two viral nonstructural proteins: NSP5 and NSP2. Inhibition of NSP5 by RNA interference results in a sharp decrease in rotavirus replication. The DLPs migrate to the endoplasmic reticulum where they obtain their third, outer layer (formed by VP7 and VP4). The progeny viruses are released from the cell by lysis.[42][61][62]

Transmission

Rotavirus is transmitted by the fæcal-oral route, via contact with contaminated hands, surfaces and objects,[63] and possibly by the respiratory route.[64] Viral diarrhea is highly contagious. The faeces of an infected person can contain more than 10 trillion infectious particles per gram;[20] fewer than 100 of these are required to transmit infection to another person.[3]

Rotaviruses are stable in the environment and have been found in estuary samples at levels up to 1–5 infectious particles per US gallon, the viruses survive between 9 and 19 days.[65] Sanitary measures adequate for eliminating bacteria and parasites seem to be ineffective in control of rotavirus, as the incidence of rotavirus infection in countries with high and low health standards is similar.[64]

Disease mechanisms

The diarrhoea is caused by multiple activities of the virus. Malabsorption occurs because of the destruction of gut cells called enterocytes. The toxic rotavirus protein NSP4 induces age- and calcium ion-dependent chloride secretion, disrupts SGLT1 transporter-mediated reabsorption of water, apparently reduces activity of brush-border membrane disaccharidases, and possibly activates the calcium ion-dependent secretory reflexes of the enteric nervous system.[51] Healthy enterocytes secrete lactase into the small intestine; milk intolerance due to lactase deficiency is a symptom of rotavirus infection,[66] which can persist for weeks.[67] A recurrence of mild diarrhoea often follows the reintroduction of milk into the child's diet, due to bacterial fermentation of the disaccharide lactose in the gut.[68]

Diagnosis and detection

Diagnosis of infection with rotavirus normally follows diagnosis of gastroenteritis as the cause of severe diarrhoea. Most children admitted to hospital with gastroenteritis are tested for rotavirus A.[69][70] Specific diagnosis of infection with rotavirus A is made by finding the virus in the child's stool by enzyme immunoassay. There are several licensed test kits on the market which are sensitive, specific and detect all serotypes of rotavirus A.[38] Other methods, such as electron microscopy and PCR, are used in research laboratories.[21] Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) can detect and identify all species and serotypes of human rotavirus.[71]

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment of acute rotavirus infection is nonspecific and involves management of symptoms and, most importantly, management of dehydration.[13] If untreated, children can die from the resulting severe dehydration.[72] Depending on the severity of diarrhoea, treatment consists of oral rehydration therapy, during which the child is given extra water to drink that contains small amounts of salt and sugar.[73] In 2004, the WHO and UNICEF recommended the use of low-osmolarity oral rehydration solution and zinc supplementation as a two-pronged treatment of acute diarrhoea.[74] Some infections are serious enough to warrant hospitalisation where fluids are given by intravenous therapy or nasogastric intubation, and the child's electrolytes and blood sugar are monitored.[69] Probiotics have been shown to reduce the duration of rotavirus diarrhoea,[75] and according to the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology "effective interventions include administration of specific probiotics such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus or Saccharomyces boulardii, diosmectite or racecadotril." [76] Rotavirus infections rarely cause other complications and for a well managed child the prognosis is excellent.[77]

Epidemiology

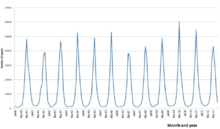

Rotavirus A, which accounts for more than 90% of rotavirus gastroenteritis in humans,[78] is endemic worldwide. Each year rotavirus causes millions of cases of diarrhoea in developing countries, almost 2 million of which result in hospitalisation.[6] In 2013, an estimated 215,000 children younger than five died from rotavirus, 90 percent of whom were in developing countries.[8] Almost every child has been infected with rotavirus by age five.[79] Rotavirus is the leading single cause of severe diarrhoea among infants and children, is responsible for about a third of the cases requiring hospitalisation,[11] and causes 37% of deaths attributable to diarrhoea and 5% of all deaths in children younger than five.[80] Boys are twice as likely as girls to be admitted to hospital for rotavirus.[81][82] Rotavirus infections occur primarily during cool, dry seasons.[83][84] The number attributable to food contamination is unknown.[85]

Outbreaks of rotavirus A diarrhoea are common among hospitalised infants, young children attending day care centres, and elderly people in nursing homes.[86] An outbreak caused by contaminated municipal water occurred in Colorado in 1981.[87] During 2005, the largest recorded epidemic of diarrhoea occurred in Nicaragua. This unusually large and severe outbreak was associated with mutations in the rotavirus A genome, possibly helping the virus escape the prevalent immunity in the population.[88] A similar large outbreak occurred in Brazil in 1977.[89]

Rotavirus B, also called adult diarrhoea rotavirus or ADRV, has caused major epidemics of severe diarrhoea affecting thousands of people of all ages in China. These epidemics occurred as a result of sewage contamination of drinking water.[90][91] Rotavirus B infections also occurred in India in 1998; the causative strain was named CAL. Unlike ADRV, the CAL strain is endemic.[92][93] To date, epidemics caused by rotavirus B have been confined to mainland China, and surveys indicate a lack of immunity to this species in the United States.[94]

Rotavirus C has been associated with rare and sporadic cases of diarrhoea in children, and small outbreaks have occurred in families.[95]

Prevention

Rotavirus is highly contagious and cannot be treated with antibiotics or other drugs. Because improved sanitation does not decrease the prevalence of rotaviral disease, and the rate of hospitalisations remains high despite the use of oral rehydrating medicines, the primary public health intervention is vaccination.[2] Two vaccines against Rotavirus A infection are approved for global use and are safe and effective in children:[15] Rotarix by GlaxoSmithKline[96] and RotaTeq by Merck.[97] Both are taken orally and contain attenuated live virus.[15] Three vaccines are licensed for use in national markets only: ROTAVAC®, licensed in India in 2014; Motavin-M1™, licensed in Vietnam in 2007; and Lanzhou Lamb Rotavirus Vaccine, licensed in China in 2000.[98] Additional rotavirus vaccines are under development.[99]

In 2009, the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended that rotavirus vaccine be included in all national immunisation programmes.[100] The incidence and severity of rotavirus infections has declined significantly in countries that have acted on this recommendation.[14][15][16] A 2014 review of available clinical trial data from countries routinely using rotavirus vaccines in their national immunisation programs found that rotavirus vaccines have reduced rotavirus hospitalisations by 49-92 percent and all cause diarrhoea hospitalisations by 17-55 percent.[101] In Mexico, which in 2006 was among the first countries in the world to introduce rotavirus vaccine, diarrhoeal disease death rates dropped during the 2009 rotavirus season by more than 65 percent among children age two and under.[102] In Nicaragua, which in 2006 became the first developing country to introduce a rotavirus vaccine, severe rotavirus infections were reduced by 40 percent and emergency room visits by a half.[103] In the United States, rotavirus vaccination since 2006 has led to drops in rotavirus-related hospitalisations by as much as 86 percent. The vaccines may also have prevented illness in non-vaccinated children by limiting the number of circulating infections.[104] In developing countries in Africa and Asia, where the majority of rotavirus deaths occur, a large number of safety and efficacy trials as well as recent post-introduction impact and effectiveness studies of Rotarix and RotaTeq have found that vaccines dramatically reduced severe disease among infants.[16][105][106][107] In September 2013, the vaccine was offered to all children in the UK, aged between two and three months, and it is expected to halve the cases of severe infection and reduce the number of children admitted to hospital because of the infection by 70 percent.[108] In Europe, hospitalisation rates following infection by rotavirus have decreased by 65% to 84% following the introduction of the vaccine.[109] Rotavirus vaccines are licensed in over 100 countries, and more than 80 countries have introduced routine rotavirus vaccination, almost half with the support of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.[110] To make rotavirus vaccines available, accessible, and affordable in all countries—particularly low- and middle-income countries in Africa and Asia where the majority of rotavirus deaths occur PATH, the WHO, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance have partnered with research institutions and governments to generate and disseminate evidence, lower prices, and accelerate introduction.[111]

Other animals

Rotaviruses infect the young of many species of animals and they are a major cause of diarrhoea in wild and reared animals worldwide.[7] As a pathogen of livestock, notably in young calves and piglets, rotaviruses cause economic loss to farmers because of costs of treatment associated with high morbidity and mortality rates.[112] These rotaviruses are a potential reservoir for genetic exchange with human rotaviruses.[112] There is evidence that animal rotaviruses can infect humans, either by direct transmission of the virus or by contributing one or several RNA segments to reassortants with human strains.[113][114]

History

In 1943, Jacob Light and Horace Hodes proved that a filterable agent in the faeces of children with infectious diarrhoea also caused scours (livestock diarrhoea) in cattle.[115] Three decades later, preserved samples of the agent were shown to be rotavirus.[116] In the intervening years, a virus in mice[117] was shown to be related to the virus causing scours.[118] In 1973, Ruth Bishop and colleagues described related viruses found in children with gastroenteritis.[4]

In 1974, Thomas Henry Flewett suggested the name rotavirus after observing that, when viewed through an electron microscope, a rotavirus particle looks like a wheel (rota in Latin);[119][120] the name was officially recognised by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses four years later.[121] In 1976, related viruses were described in several other species of animals.[118] These viruses, all causing acute gastroenteritis, were recognised as a collective pathogen affecting humans and animals worldwide.[119] Rotavirus serotypes were first described in 1980,[122] and in the following year, rotavirus from humans was first grown in cell cultures derived from monkey kidneys, by adding trypsin (an enzyme found in the duodenum of mammals and now known to be essential for rotavirus to replicate) to the culture medium.[123] The ability to grow rotavirus in culture accelerated the pace of research, and by the mid-1980s the first candidate vaccines were being evaluated.[124]

In 1998, a rotavirus vaccine was licensed for use in the United States. Clinical trials in the United States, Finland, and Venezuela had found it to be 80 to 100% effective at preventing severe diarrhoea caused by rotavirus A, and researchers had detected no statistically significant serious adverse effects.[125][126] The manufacturer, however, withdrew it from the market in 1999, after it was discovered that the vaccine may have contributed to an increased risk for intussusception, a type of bowel obstruction, in one of every 12,000 vaccinated infants.[127] The experience provoked intense debate about the relative risks and benefits of a rotavirus vaccine.[128] In 2006, two new vaccines against rotavirus A infection were shown to be safe and effective in children,[129] and in June 2009 the World Health Organization recommended that rotavirus vaccination be included in all national immunisation programmes to provide protection against this virus.[130]

References

- ↑ Dennehy PH (2015). "Rotavirus Infection: A Disease of the Past?". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 29 (4): 617–35. PMID 26337738. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.07.002.

- 1 2 Bernstein DI (March 2009). "Rotavirus overview". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 28 (3 Suppl): S50–3. PMID 19252423. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967bee.

- 1 2 3 Grimwood K, Lambert SB (February 2009). "Rotavirus vaccines: opportunities and challenges". Human Vaccines. 5 (2): 57–69. PMID 18838873. doi:10.4161/hv.5.2.6924.

- 1 2 Bishop R (October 2009). "Discovery of rotavirus: Implications for child health". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 24 (Suppl 3): S81–5. PMID 19799704. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06076.x.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2015). "Global Rotavirus Sentinel Hospital Surveillance Network" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 Simpson E, Wittet S, Bonilla J, Gamazina K, Cooley L, Winkler JL (2007). "Use of formative research in developing a knowledge translation approach to rotavirus vaccine introduction in developing countries". BMC Public Health. 7: 281. PMC 2173895

. PMID 17919334. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-281.

. PMID 17919334. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-281. - 1 2 Edward J Dubovi; Nigel James MacLachlan (2010). Fenner's Veterinary Virology, Fourth Edition. Boston: Academic Press. p. 288. ISBN 0-12-375158-6.

- 1 2 Tate, Jacqueline E.; Burton, Anthony H.; Boschi-Pinto, Cynthia; Parashar, Umesh D. (2016). "Global, Regional, and National Estimates of Rotavirus Mortality in Children <5 Years of Age, 2000–2013". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 62 (Suppl 2): S96–S105. PMID 27059362. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1013.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2008). "Global networks for surveillance of rotavirus gastroenteritis, 2001–2008" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 83 (47): 421–428. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Fischer TK, Viboud C, Parashar U, et al. (2007). "Hospitalizations and deaths from diarrhea and rotavirus among children <5 years of age in the United States, 1993–2003". J. Infect. Dis. 195 (8): 1117–25. PMID 17357047. doi:10.1086/512863.

- 1 2 Leshem, Eyal; Moritz, Rebecca E.; Curns, Aaron T.; et al. (2014). "Rotavirus Vaccines and Health Care Utilization for Diarrhea in the United States (2007–2011)". Pediatrics. 134 (1): 15–23.

- ↑ Tate JE, Cortese MM, Payne DC, Curns AT, Yen C, Esposito DH, Cortes JE, Lopman BA, Patel MM, Gentsch JR, Parashar UD (January 2011). "Uptake, impact, and effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination in the United States: review of the first 3 years of postlicensure data". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 30 (1 Suppl): S56–60. PMID 21183842. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefdc0.

- 1 2 Diggle L (2007). "Rotavirus diarrhea and future prospects for prevention". Br. J. Nurs. 16 (16): 970–4. PMID 18026034.

- 1 2 Giaquinto C, Dominiak-Felden G, Van Damme P, Myint TT, Maldonado YA, Spoulou V, Mast TC, Staat MA (July 2011). "Summary of effectiveness and impact of rotavirus vaccination with the oral pentavalent rotavirus vaccine: a systematic review of the experience in industrialized countries". Human Vaccines. 7 (7): 734–48. PMID 21734466. doi:10.4161/hv.7.7.15511.

- 1 2 3 4 Jiang V, Jiang B, Tate J, Parashar UD, Patel MM (July 2010). "Performance of rotavirus vaccines in developed and developing countries". Human Vaccines. 6 (7): 532–42. PMC 3322519

. PMID 20622508. doi:10.4161/hv.6.7.11278.

. PMID 20622508. doi:10.4161/hv.6.7.11278. - 1 2 3 Parashar, Umesh D.; Tate, Jacqueline E., eds. (2016). "Health Benefits of Rotavirus Vaccination in Developing Countries". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 62 (Suppl 2): S91–S228. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1015.

- ↑ Hochwald C, Kivela L (1999). "Rotavirus vaccine, live, oral, tetravalent (RotaShield)". Pediatr. Nurs. 25 (2): 203–4, 207. PMID 10532018.

- ↑ Maldonado YA, Yolken RH (1990). "Rotavirus". Baillière's Clinical Gastroenterology. 4 (3): 609–25. PMID 1962726. doi:10.1016/0950-3528(90)90052-I.

- ↑ Glass RI, Parashar UD, Bresee JS, Turcios R, Fischer TK, Widdowson MA, Jiang B, Gentsch JR (July 2006). "Rotavirus vaccines: current prospects and future challenges". Lancet. 368 (9532): 323–32. PMID 16860702. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68815-6.

- 1 2 3 Bishop RF (1996). "Natural history of human rotavirus infection". Arch. Virol. Suppl. 12: 119–28. PMID 9015109.

- 1 2 Offit PA (2001). Gastroenteritis viruses. New York: Wiley. pp. 106–124. ISBN 0-471-49663-4.

- ↑ Ward R (March 2009). "Mechanisms of protection against rotavirus infection and disease". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 28 (3 Suppl): S57–9. PMID 19252425. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967c16.

- 1 2 Ramsay M, Brown D (2000). Desselberger, U., Gray, James, eds. Rotaviruses: methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 217. ISBN 0-89603-736-3.Free ebook

- ↑ Hrdy DB (1987). "Epidemiology of rotaviral infection in adults". Rev. Infect. Dis. 9 (3): 461–9. PMID 3037675. doi:10.1093/clinids/9.3.461.

- ↑ "Virus Taxonomy: 2014 Release". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

- 1 2 Kirkwood CD (September 2010). "Genetic and antigenic diversity of human rotaviruses: potential impact on vaccination programs". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 202 (Suppl): S43–8. PMID 20684716. doi:10.1086/653548.

- ↑ Wakuda M, Ide T, Sasaki J, Komoto S, Ishii J, Sanekata T, Taniguchi K (2011). "Porcine rotavirus closely related to novel group of human rotaviruses". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (8): 1491–3. PMC 3381553

. PMID 21801631. doi:10.3201/eid1708.101466.

. PMID 21801631. doi:10.3201/eid1708.101466. - ↑ Marthaler D, Rossow K, Culhane M, Goyal S, Collins J, Matthijnssens J, Nelson M, Ciarlet M (2014). "Widespread rotavirus H in commercially raised pigs, United States". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (7): 1195–8. PMC 4073875

. PMID 24960190. doi:10.3201/eid2007.140034.

. PMID 24960190. doi:10.3201/eid2007.140034. - ↑ O'Ryan M (March 2009). "The ever-changing landscape of rotavirus serotypes". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 28 (3 Suppl): S60–2. PMID 19252426. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967c29.

- ↑ Patton JT (January 2012). "Rotavirus diversity and evolution in the post-vaccine world". Discovery Medicine. 13 (68): 85–97. PMC 3738915

. PMID 22284787.

. PMID 22284787. - ↑ Desselberger U, Wolleswinkel-van den Bosch J, Mrukowicz J, Rodrigo C, Giaquinto C, Vesikari T (2006). "Rotavirus types in Europe and their significance for vaccination". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25 (1 Suppl.): S30–41. PMID 16397427. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000197707.70835.f3.

- 1 2 Pesavento JB, Crawford SE, Estes MK, Prasad BV (2006). "Rotavirus proteins: structure and assembly". Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 309: 189–219. ISBN 978-3-540-30772-3. PMID 16913048. doi:10.1007/3-540-30773-7_7.

- ↑ Prasad BV, Chiu W (1994). "Structure of rotavirus". Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 185: 9–29. PMID 8050286.

- ↑ Patton JT (1995). "Structure and function of the rotavirus RNA-binding proteins" (PDF). J. Gen. Virol. 76 (11): 2633–44. PMID 7595370. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-76-11-2633.

- ↑ Patton JT (2001). "Rotavirus RNA replication and gene expression". Novartis Found. Symp. Novartis Foundation Symposia. 238: 64–77; discussion 77–81. ISBN 9780470846537. PMID 11444036. doi:10.1002/0470846534.ch5.

- ↑ Vásquez-del Carpió R, Morales JL, Barro M, Ricardo A, Spencer E (2006). "Bioinformatic prediction of polymerase elements in the rotavirus VP1 protein". Biol. Res. 39 (4): 649–59. PMID 17657346. doi:10.4067/S0716-97602006000500008.

- ↑ Arnoldi F, Campagna M, Eichwald C, Desselberger U, Burrone OR (2007). "Interaction of rotavirus polymerase VP1 with nonstructural protein NSP5 is stronger than that with NSP2". J. Virol. 81 (5): 2128–37. PMC 1865955

. PMID 17182692. doi:10.1128/JVI.01494-06.

. PMID 17182692. doi:10.1128/JVI.01494-06. - 1 2 Angel J, Franco MA, Greenberg HB (2009). Mahy BW, Van Regenmortel MH, eds. Desk Encyclopedia of Human and Medical Virology. Boston: Academic Press. p. 277. ISBN 0-12-375147-0.

- ↑ Cowling VH (January 2010). "Regulation of mRNA cap methylation". Biochem. J. 425 (2): 295–302. PMC 2825737

. PMID 20025612. doi:10.1042/BJ20091352.

. PMID 20025612. doi:10.1042/BJ20091352. - ↑ Gardet A, Breton M, Fontanges P, Trugnan G, Chwetzoff S (2006). "Rotavirus spike protein VP4 binds to and remodels actin bundles of the epithelial brush border into actin bodies". J. Virol. 80 (8): 3947–56. PMC 1440440

. PMID 16571811. doi:10.1128/JVI.80.8.3947-3956.2006.

. PMID 16571811. doi:10.1128/JVI.80.8.3947-3956.2006. - ↑ Arias CF, Isa P, Guerrero CA, Méndez E, Zárate S, López T, Espinosa R, Romero P, López S (2002). "Molecular biology of rotavirus cell entry". Arch. Med. Res. 33 (4): 356–61. PMID 12234525. doi:10.1016/S0188-4409(02)00374-0.

- 1 2 Jayaram H, Estes MK, Prasad BV (April 2004). "Emerging themes in rotavirus cell entry, genome organization, transcription and replication". Virus Research. 101 (1): 67–81. PMID 15010218. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.007.

- ↑ Hoshino Y, Jones RW, Kapikian AZ (2002). "Characterization of neutralization specificities of outer capsid spike protein VP4 of selected murine, lapine, and human rotavirus strains". Virology. 299 (1): 64–71. PMID 12167342. doi:10.1006/viro.2002.1474.

- ↑ Beards GM, Campbell AD, Cottrell NR, Peiris JS, Rees N, Sanders RC, Shirley JA, Wood HC, Flewett TH (1 February 1984). "Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays based on polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies for rotavirus detection" (PDF). J. Clin. Microbiol. 19 (2): 248–54. PMC 271031

. PMID 6321549.

. PMID 6321549. - ↑ Hua J, Mansell EA, Patton JT (1993). "Comparative analysis of the rotavirus NS53 gene: conservation of basic and cysteine-rich regions in the protein and possible stem-loop structures in the RNA". Virology. 196 (1): 372–8. PMID 8395125. doi:10.1006/viro.1993.1492.

- ↑ Arnold MM (2016). "The Rotavirus Interferon Antagonist NSP1: Many Targets, Many Questions". Journal of Virology. 90 (11): 5212–5. PMID 27009959. doi:10.1128/JVI.03068-15.

- ↑ Kattoura MD, Chen X, Patton JT (1994). "The rotavirus RNA-binding protein NS35 (NSP2) forms 10S multimers and interacts with the viral RNA polymerase". Virology. 202 (2): 803–13. PMID 8030243. doi:10.1006/viro.1994.1402.

- ↑ Taraporewala ZF, Patton JT (2004). "Nonstructural proteins involved in genome packaging and replication of rotaviruses and other members of the Reoviridae". Virus Res. 101 (1): 57–66. PMID 15010217. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.006.

- ↑ Poncet D, Aponte C, Cohen J (1 June 1993). "Rotavirus protein NSP3 (NS34) is bound to the 3' end consensus sequence of viral mRNAs in infected cells" (PDF). J. Virol. 67 (6): 3159–65. PMC 237654

. PMID 8388495.

. PMID 8388495. - ↑ López, S; Arias, CF (August 2012). "Rotavirus-host cell interactions: an arms race.". Current Opinion in Virology. 2 (4): 389–98. PMID 22658208. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2012.05.001.

- 1 2 Hyser JM, Estes MK (January 2009). "Rotavirus vaccines and pathogenesis: 2008". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 25 (1): 36–43. PMC 2673536

. PMID 19114772. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e328317c897.

. PMID 19114772. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e328317c897. - ↑ Afrikanova I, Miozzo MC, Giambiagi S, Burrone O (1996). "Phosphorylation generates different forms of rotavirus NSP5". J. Gen. Virol. 77 (9): 2059–65. PMID 8811003. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-77-9-2059.

- ↑ Rainsford EW, McCrae MA (2007). "Characterization of the NSP6 protein product of rotavirus gene 11". Virus Res. 130 (1–2): 193–201. PMID 17658646. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.06.011.

- ↑ Mohan KV, Atreya CD (2001). "Nucleotide sequence analysis of rotavirus gene 11 from two tissue culture-adapted ATCC strains, RRV and Wa". Virus Genes. 23 (3): 321–9. PMID 11778700. doi:10.1023/A:1012577407824.

- ↑ Desselberger U. Rotavirus: basic facts. In Rotaviruses Methods and Protocols. Ed. Gray, J. and Desselberger U. Humana Press, 2000, pp. 1–8. ISBN 0-89603-736-3

- ↑ Patton JT. Rotavirus RNA replication and gene expression. In Novartis Foundation. Gastroenteritis Viruses, Humana Press, 2001, pp. 64–81. ISBN 0-471-49663-4

- ↑ Claude M. Fauquet; J. Maniloff; Desselberger, U. (2005). Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses: 8th report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press. p. 489. ISBN 0-12-249951-4.

- ↑ Greenberg HB, Estes MK (May 2009). "Rotaviruses: from pathogenesis to vaccination". Gastroenterology. 136 (6): 1939–51. PMC 3690811

. PMID 19457420. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.076.

. PMID 19457420. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.076. - ↑ Greenberg HB, Clark HF, Offit PA (1994). "Rotavirus pathology and pathophysiology". Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 185: 255–83. PMID 8050281.

- ↑ Baker M, Prasad BV (2010). "Rotavirus cell entry". Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 343: 121–48. ISBN 978-3-642-13331-2. PMID 20397068. doi:10.1007/82_2010_34.

- ↑ Patton JT, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Spencer E (2004). "Replication and transcription of the rotavirus genome". Curr. Pharm. Des. 10 (30): 3769–77. PMID 15579070. doi:10.2174/1381612043382620.

- ↑ Ruiz MC, Leon T, Diaz Y, Michelangeli F (2009). "Molecular biology of rotavirus entry and replication". TheScientificWorldJournal. 9: 1476–97. PMID 20024520. doi:10.1100/tsw.2009.158.

- ↑ Butz AM, Fosarelli P, Dick J, Cusack T, Yolken R (1993). "Prevalence of rotavirus on high-risk fomites in day-care facilities". Pediatrics. 92 (2): 202–5. PMID 8393172.

- 1 2 Dennehy PH (2000). "Transmission of rotavirus and other enteric pathogens in the home". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19 (10 Suppl): S103–5. PMID 11052397. doi:10.1097/00006454-200010001-00003.

- ↑ Rao VC, Seidel KM, Goyal SM, Metcalf TG, Melnick JL (1 August 1984). "Isolation of enteroviruses from water, suspended solids, and sediments from Galveston Bay: survival of poliovirus and rotavirus adsorbed to sediments" (PDF). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48 (2): 404–9. PMC 241526

. PMID 6091548.

. PMID 6091548. - ↑ Farnworth ER (June 2008). "The evidence to support health claims for probiotics". The Journal of Nutrition. 138 (6): 1250S–4S. PMID 18492865.

- ↑ Ouwehand A, Vesterlund S (2003). "Health aspects of probiotics". IDrugs. 6 (6): 573–80. PMID 12811680.

- ↑ Arya SC (1984). "Rotaviral infection and intestinal lactase level". J. Infect. Dis. 150 (5): 791. PMID 6436397. doi:10.1093/infdis/150.5.791.

- 1 2 Patel MM, Tate JE, Selvarangan R, Daskalaki I, Jackson MA, Curns AT, Coffin S, Watson B, Hodinka R, Glass RI, Parashar UD (October 2007). "Routine laboratory testing data for surveillance of rotavirus hospitalizations to evaluate the impact of vaccination". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 26 (10): 914–9. PMID 17901797. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31812e52fd.

- ↑ The Pediatric ROTavirus European CommitTee (PROTECT) (2006). "The paediatric burden of rotavirus disease in Europe". Epidemiol. Infect. 134 (5): 908–16. PMC 2870494

. PMID 16650331. doi:10.1017/S0950268806006091.

. PMID 16650331. doi:10.1017/S0950268806006091. - ↑ Fischer TK, Gentsch JR (2004). "Rotavirus typing methods and algorithms". Reviews in Medical Virology. 14 (2): 71–82. PMID 15027000. doi:10.1002/rmv.411.

- ↑ Alam NH, Ashraf H (2003). "Treatment of infectious diarrhea in children". Paediatr. Drugs. 5 (3): 151–65. PMID 12608880. doi:10.2165/00128072-200305030-00002.

- ↑ Sachdev HP (1996). "Oral rehydration therapy". Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 94 (8): 298–305. PMID 8855579.

- ↑ World Health Organization, UNICEF. "Joint Statement: Clinical Management of Acute Diarrhoea" (PDF). Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Ahmadi E, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Rezai MS (2015). "Efficacy of probiotic use in acute rotavirus diarrhea in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Caspian J Intern Med. 6 (4): 187–95.

- ↑ Guarino A1, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, Lo Vecchio A, Shamir R, Szajewska H (2014). "European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: update 2014.". J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 59 (1): 132–52. doi:10.1097/mpg.0000000000000375.

- ↑ Ramig RF (August 2007). "Systemic rotavirus infection". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 5 (4): 591–612. PMID 17678424. doi:10.1586/14787210.5.4.591.

- ↑ Leung AK, Kellner JD, Davies HD (2005). "Rotavirus gastroenteritis". Adv. Ther. 22 (5): 476–87. PMID 16418157. doi:10.1007/BF02849868.

- ↑ Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresse JS, Glass RI (2006). "Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (2): 304–6. PMC 3373114

. PMID 16494759. doi:10.3201/eid1202.050006.

. PMID 16494759. doi:10.3201/eid1202.050006. - ↑ Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD (February 2012). "2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet Infect Dis. 12 (2): 136–141. PMID 22030330. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5.

- ↑ Rheingans RD, Heylen J, Giaquinto C (2006). "Economics of rotavirus gastroenteritis and vaccination in Europe: what makes sense?". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25 (1 Suppl): S48–55. PMID 16397429. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000197566.47750.3d.

- ↑ Ryan MJ, Ramsay M, Brown D, Gay NJ, Farrington CP, Wall PG (1996). "Hospital admissions attributable to rotavirus infection in England and Wales". J. Infect. Dis. 174 (Suppl 1): S12–8. PMID 8752285. doi:10.1093/infdis/174.Supplement_1.S12.

- ↑ Atchison CJ, Tam CC, Hajat S, van Pelt W, Cowden JM, Lopman BA (March 2010). "Temperature-dependent transmission of rotavirus in Great Britain and The Netherlands". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1683): 933–42. PMC 2842727

. PMID 19939844. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1755.

. PMID 19939844. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1755. - ↑ Levy K, Hubbard AE, Eisenberg JN (December 2009). "Seasonality of rotavirus disease in the tropics: a systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Epidemiology. 38 (6): 1487–96. PMC 2800782

. PMID 19056806. doi:10.1093/ije/dyn260.

. PMID 19056806. doi:10.1093/ije/dyn260. - ↑ Koopmans M, Brown D (1999). "Seasonality and diversity of Group A rotaviruses in Europe". Acta Paediatrica Supplement. 88 (426): 14–9. PMID 10088906. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb14320.x.

- ↑ Anderson EJ, Weber SG (February 2004). "Rotavirus infection in adults". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 4 (2): 91–9. PMID 14871633. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00928-4.

- ↑ Hopkins RS, Gaspard GB, Williams FP, Karlin RJ, Cukor G, Blacklow NR (1984). "A community waterborne gastroenteritis outbreak: evidence for rotavirus as the agent". American Journal of Public Health. 74 (3): 263–5. PMC 1651463

. PMID 6320684. doi:10.2105/AJPH.74.3.263.

. PMID 6320684. doi:10.2105/AJPH.74.3.263. - ↑ Bucardo F, Karlsson B, Nordgren J, et al. (2007). "Mutated G4P[8] rotavirus associated with a nationwide outbreak of gastroenteritis in Nicaragua in 2005". J. Clin. Microbiol. 45 (3): 990–7. PMC 1829148

. PMID 17229854. doi:10.1128/JCM.01992-06.

. PMID 17229854. doi:10.1128/JCM.01992-06. - ↑ Linhares AC, Pinheiro FP, Freitas RB, Gabbay YB, Shirley JA, Beards GM (1981). "An outbreak of rotavirus diarrhea among a non-immune, isolated South American Indian community". Am. J. Epidemiol. 113 (6): 703–10. PMID 6263087.

- ↑ Hung T, Chen GM, Wang CG, et al. (1984). "Waterborne outbreak of rotavirus diarrhea in adults in China caused by a novel rotavirus". Lancet. 1 (8387): 1139–42. PMID 6144874. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91391-6.

- ↑ Fang ZY, Ye Q, Ho MS, et al. (1989). "Investigation of an outbreak of adult diarrhea rotavirus in China". J. Infect. Dis. 160 (6): 948–53. PMID 2555422. doi:10.1093/infdis/160.6.948.

- ↑ Kelkar SD, Zade JK (2004). "Group B rotaviruses similar to strain CAL-1, have been circulating in Western India since 1993". Epidemiol. Infect. 132 (4): 745–9. PMC 2870156

. PMID 15310177. doi:10.1017/S0950268804002171.

. PMID 15310177. doi:10.1017/S0950268804002171. - ↑ Ahmed MU, Kobayashi N, Wakuda M, Sanekata T, Taniguchi K, Kader A, Naik TN, Ishino M, Alam MM, Kojima K, Mise K, Sumi A (2004). "Genetic analysis of group B human rotaviruses detected in Bangladesh in 2000 and 2001". J. Med. Virol. 72 (1): 149–55. PMID 14635024. doi:10.1002/jmv.10546.

- ↑ Penaranda ME, Ho MS, Fang ZY, et al. (1 October 1989). "Seroepidemiology of adult diarrhea rotavirus in China, 1977 to 1987" (PDF). J. Clin. Microbiol. 27 (10): 2180–3. PMC 266989

. PMID 2479654.

. PMID 2479654. - ↑ Desselberger U, Iturriza-Gomera, Gray JJ (2001). Gastroenteritis viruses. New York: Wiley. pp. 127–128. ISBN 0-471-49663-4.

- ↑ O'Ryan M (2007). "Rotarix (RIX4414): an oral human rotavirus vaccine". Expert review of vaccines. 6 (1): 11–9. PMID 17280473. doi:10.1586/14760584.6.1.11.

- ↑ Matson DO (2006). "The pentavalent rotavirus vaccine, RotaTeq". Seminars in paediatric infectious diseases. 17 (4): 195–9. PMID 17055370. doi:10.1053/j.spid.2006.08.005.

- ↑ Rota Council (2016). Rotavirus: Common, Severe, Devastating, Preventable (PDF).

- ↑ Ward RL, Clark HF, Offit PA (September 2010). "Influence of potential protective mechanisms on the development of live rotavirus vaccines". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 202 (Suppl): S72–9. PMID 20684721. doi:10.1086/653549.

- ↑ Tate JE, Patel MM, Steele AD, Gentsch JR, Payne DC, Cortese MM, Nakagomi O, Cunliffe NA, Jiang B, Neuzil KM, de Oliveira LH, Glass RI, Parashar UD (April 2010). "Global impact of rotavirus vaccines". Expert Review of Vaccines. 9 (4): 395–407. PMID 20370550. doi:10.1586/erv.10.17.

- ↑ Tate, Jacqueline E.; Parashar, Umesh D. (2014). "Rotavirus Vaccines in Routine Use". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 59 (9): 1291–1301. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu564.

- ↑ Richardson, V; Hernandez-Pichardo J; et al. (2010). "Effect of Rotavirus Vaccination on Death From Childhood Diarrhea in Mexico". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (4): 299–305. PMID 20107215. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905211.

- ↑ Patel M, Pedreira C, De Oliveira LH, et al. (August 2012). "Duration of protection of pentavalent rotavirus vaccination in Nicaragua". Pediatrics. 130 (2): e365–72. PMID 22753550. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3478.

- ↑ Patel MM, Parashar UD, eds. (January 2011). "Real World Impact of Rotavirus Vaccination". Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 30 (Supplement): S1. PMID 21183833. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefa1f. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ Steele, A. Duncan; Armah, George E.; Page, Nicola A.; Cunliffe, Nigel A., eds. (2010). "Rotavirus Infection in Africa: Epidemiology, Burden of Disease, and Strain Diversity". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 202 (Suppl 1): S1–S265.

- ↑ Nelson, E. Anthony S.; Widdowson, Marc-Alain; Kilgore, Paul E.; Steele, Duncan; Parashar, Umesh D., eds. (2009). "Rotavirus in Asia: Updates on Disease Burden, Genotypes and Vaccine Introduction". Vaccine. 27 (Suppl 5): F1–F138.

- ↑ World Health Organization (December 2009). "Rotavirus vaccines: an update" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 51–52 (84): 533–540. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ UK Department of Health: New vaccine to help protect babies against rotavirus. Retrieved on 10 November, 2012

- ↑ Karafillakis E, Hassounah S, Atchison C (2015). "Effectiveness and impact of rotavirus vaccines in Europe, 2006-2014". Vaccine. 33 (18): 2097–107. PMID 25795258. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.016.

- ↑ "Rotavirus Deaths & Rotavirus Vaccine Introduction Maps – ROTA Council". rotacouncil.org. Retrieved 2016-07-29.

- ↑ Moszynski P (2011). "GAVI rolls out vaccines against child killers to more countries". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 343: d6217. PMID 21957215. doi:10.1136/bmj.d6217.

- 1 2 Martella V, Bányai K, Matthijnssens J, Buonavoglia C, Ciarlet M (January 2010). "Zoonotic aspects of rotaviruses". Veterinary Microbiology. 140 (3–4): 246–55. PMID 19781872. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.028.

- ↑ Müller H, Johne R (2007). "Rotaviruses: diversity and zoonotic potential—a brief review". Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 120 (3–4): 108–12. PMID 17416132.

- ↑ Cook N, Bridger J, Kendall K, Gomara MI, El-Attar L, Gray J (2004). "The zoonotic potential of rotavirus". J. Infect. 48 (4): 289–302. PMID 15066329. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2004.01.018.

- ↑ Light JS, Hodes HL (1943). "Studies on epidemic diarrhea of the new-born: Isolation of a Filtrable Agent Causing Diarrhea in Calves". Am. J. Public Health Nations Health. 33 (12): 1451–4. PMC 1527675

. PMID 18015921. doi:10.2105/AJPH.33.12.1451.

. PMID 18015921. doi:10.2105/AJPH.33.12.1451. - ↑ Mebus CA, Wyatt RG, Sharpee RL, et al. (1 August 1976). "Diarrhea in gnotobiotic calves caused by the reovirus-like agent of human infantile gastroenteritis" (PDF). Infect. Immun. 14 (2): 471–4. PMC 420908

. PMID 184047.

. PMID 184047. - ↑ Rubenstein D, Milne RG, Buckland R, Tyrrell DA (1971). "The growth of the virus of epidemic diarrhoea of infant mice (EDIM) in organ cultures of intestinal epithelium". British journal of experimental pathology. 52 (4): 442–45. PMC 2072337

. PMID 4998842.

. PMID 4998842. - 1 2 Woode GN, Bridger JC, Jones JM, Flewett TH, Davies HA, Davis HA, White GB (1 September 1976). "Morphological and antigenic relationships between viruses (rotaviruses) from acute gastroenteritis in children, calves, piglets, mice, and foals" (PDF). Infect. Immun. 14 (3): 804–10. PMC 420956

. PMID 965097.

. PMID 965097. - 1 2 Flewett TH, Woode GN (1978). "The rotaviruses". Arch. Virol. 57 (1): 1–23. PMID 77663. doi:10.1007/BF01315633.

- ↑ Flewett TH, Bryden AS, Davies H, Woode GN, Bridger JC, Derrick JM (1974). "Relation between viruses from acute gastroenteritis of children and newborn calves". Lancet. 2 (7872): 61–3. PMID 4137164. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91631-6.

- ↑ Matthews RE (1979). "Third report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Classification and nomenclature of viruses". Intervirology. 12 (3–5): 129–296. PMID 43850. doi:10.1159/000149081.

- ↑ Beards GM, Brown DW (March 1988). "The antigenic diversity of rotaviruses: significance to epidemiology and vaccine strategies". European Journal of Epidemiology. 4 (1): 1–11. PMID 2833405. doi:10.1007/BF00152685.

- ↑ Urasawa T, Urasawa S, Taniguchi K (1981). "Sequential passages of human rotavirus in MA-104 cells". Microbiol. Immunol. 25 (10): 1025–35. PMID 6273696. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.1981.tb00109.x.

- ↑ Ward RL, Bernstein DI (January 2009). "Rotarix: a rotavirus vaccine for the world". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (2): 222–8. PMID 19072246. doi:10.1086/595702.

- ↑ "Rotavirus vaccine for the prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)". MMWR Recomm Rep. 48 (RR–2): 1–20. 1999. PMID 10219046.

- ↑ Kapikian AZ (2001). "A rotavirus vaccine for prevention of severe diarrhoea of infants and young children: development, utilization and withdrawal". Novartis Found. Symp. Novartis Foundation Symposia. 238: 153–71; discussion 171–9. ISBN 9780470846537. PMID 11444025. doi:10.1002/0470846534.ch10.

- ↑ Bines JE (2005). "Rotavirus vaccines and intussusception risk". Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 21 (1): 20–5. PMID 15687880.

- ↑ Bines J (2006). "Intussusception and rotavirus vaccines". Vaccine. 24 (18): 3772–6. PMID 16099078. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.031.

- ↑ Dennehy PH (2008). "Rotavirus vaccines: an overview". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21 (1): 198–208. PMC 2223838

. PMID 18202442. doi:10.1128/CMR.00029-07.

. PMID 18202442. doi:10.1128/CMR.00029-07. - ↑ "Meeting of the immunization Strategic Advisory Group of Experts, April 2009—conclusions and recommendations". Relevé Épidémiologique Hebdomadaire / Section D'hygiène Du Secrétariat De La Société Des Nations = Weekly Epidemiological Record / Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations. 84 (23): 220–36. June 2009. PMID 19499606.

External links

| Classification |

V · T · D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rotavirus. |

- WHO Rotavirus web page

- Rotavirus on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) site

- Viralzone: Rotavirus

- Vaccine Resource Library: Rotavirus

- DefeatDD.org

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012). "Ch. 18: Rotavirus". In Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky J. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (12th ed.). Washington DC: Public Health Foundation. pp. 263–274.

- 3D macromolecular structures of Rotaviruses from the EM Data Bank(EMDB)

- ROTA Council