Roots-type supercharger

The Roots type blower is a positive displacement lobe pump which operates by pumping a fluid with a pair of meshing lobes not unlike a set of stretched gears. Fluid is trapped in pockets surrounding the lobes and carried from the intake side to the exhaust. The most common application of the Roots type blower has been as the induction device on two-stroke Diesel engines, such as those produced by Detroit Diesel and Electro-Motive Diesel. Roots type blowers are also used to supercharge Otto cycle engines, with the blower being driven from the engine's crankshaft via a toothed or V-belt, a roller chain or a gear train.

The Roots type blower is named after the American inventors and brothers Philander and Francis Marion Roots, founders of the Roots Blower Company of Connersville, Indiana USA, who patented the basic design in 1860 as an air pump for use in blast furnaces and other industrial applications. In 1900, Gottlieb Daimler included a Roots-style blower in a patented engine design, making the Roots-type blower the oldest of the various designs now available. Roots blowers are commonly referred to as air blowers or PD (positive displacement) blowers,[1] and can be commonly called "huffers" when used with the gasoline-burning engines in hot rod customized cars.[2]

Applications

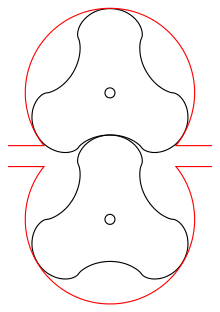

The Roots-type blower is simple and widely used. It can be more effective than alternative superchargers at developing positive intake manifold pressure (i.e., above atmospheric pressure) at low engine speeds, making it a popular choice for passenger automobile applications. Peak torque can be achieved by about 2000 rpm. Unlike the basic illustration, most modern Roots-type superchargers incorporate three-lobe or four-lobe rotors; this allows the lobes to have a slight twist along the rotor axes, which in turn reduces pulsing in the input and output (this is impractical with two lobes, as even a slight twist could open up a free path through the supercharger at certain angles).

Accumulated heat is an important consideration in the operation of a compressor in an internal combustion engine. Of the three basic supercharger types, the Roots design historically possessed the worst thermal efficiency, especially at high pressure ratios.[3] In accordance with the ideal gas law, a compression operation will raise the temperature of the compressed output. Additionally, the operation of the compressor itself requires energy input, which is converted to heat and can be transferred to the gas through the compressor housing, heating it more. Although intercoolers are more commonly known for their use on turbochargers, superchargers may also benefit from the use of an intercooler. Internal combustion is based upon a thermodynamic cycle, and a cooler temperature of the intake charge results in a greater thermodynamic expansion and vice versa. A hot intake charge provokes detonation in a petrol engine, and can melt the pistons in a diesel, while an intercooling stage adds complexity but can improve the power output by increasing the amount of the input charge, exactly as if the engine were of higher capacity. An intercooler reduces the thermodynamic efficiency by losing the heat (power) introduced by compression, but increases the power available because of the increased working mass for each cycle. Above about 5 psi (0.3 bar) the intercooling improvement can become dramatic. With a Roots-type supercharger, one method successfully employed is the addition of a thin heat exchanger placed between the blower and the engine. Water is circulated through it to a second unit placed near the front of the vehicle where a fan and the ambient air-stream can dissipate the collected heat.

The Roots design was commonly used on two-stroke diesel engines (popularized by the Detroit Diesel [truck and bus] and Electro-Motive [railroad] divisions of General Motors), which require some form of forced induction, as there is no separate intake stroke. The Rootes Co. two-stroke diesel engine, used in Commer and Karrier vehicles, had a Roots-type blower but the two names are not connected.

The superchargers used on top fuel engines, funny cars, and other dragsters, as well as hot rods, are in fact derivatives of General Motors Coach Division blowers for their industrial diesel engines, which were adapted for automotive use in the early days of the sport of drag racing. The model name of these units delineates their size; i.e. the once commonly used "4–71" and "6–71" blowers were designed for General Motors diesels having four or six cylinders of 71 cubic inches each. Current competition dragsters use aftermarket GMC variants similar in design to the −71 series, but with the rotor and case length increased for added pumping capacity, identified as the 8–71, 12–71, 16–71, etc.

Roots blowers are typically used in applications where a large volume of air must be moved across a relatively small pressure differential. This includes low vacuum applications, with the Roots blower acting alone, or use as part of a high vacuum system, in combination with other pumps.

Some civil defense sirens used Roots blowers to pump air to the rotor (chopper). The most well known are the Federal Signal Thunderbolt Series, and ACA (now American Signal Corporation) Hurricane. These sirens are known as "supercharged sirens".

Roots blowers are also used in reverse to measure the flow of gases or liquids, for example, in gas meters.

Technical considerations

The simplest form of a Roots blower has cycloidal rotors, constructed of alternating tangential sections of hypocycloidal and epicycloidal curves. For a two-lobed rotor, the smaller generating circles are one-quarter the diameter of the larger. Real Roots blowers may have more complex profiles for increased efficiency. The lobes on one rotor will not drive the other rotor with minimal free play in all positions, so that a separate pair of gears provide the phasing of the lobes.

Because rotary lobe pumps need to maintain a clearance between the lobes, a single stage Roots blower can pump gas across only a limited pressure differential. If the pump is used outside its specification, the compression of the gas generates so much heat that the lobes expand to the point that they jam, damaging the pump.

Roots pumps are capable of pumping large volumes but, as they only achieve moderate compression, it is not uncommon to see multiple Roots blower stages, frequently with heat exchangers (intercoolers) in between to cool the gas. The lack of oil on the pumping surfaces allows the pumps to work in environments where contamination control is important. The high pumping rate for hydrocarbons also allows the Roots pump to provide an effective isolation between oiled pumps, such as rotary compression pumps, and the vacuum chamber.

A variant uses claw-shaped rotors for higher compression.

The Roots-type blower may achieve an efficiency of around 70% while achieving a maximum pressure ratio of two. Because a Roots type blower pumps air in discrete pulses (unlike a screw compressor), pulsation noise and turbulence may be transmitted downstream. If not properly managed (through outlet piping geometry) or accounted for (by structural reinforcement of downstream components), the resulting pulsations can cause fluid cavitation and/or damage to components downstream of the blower.

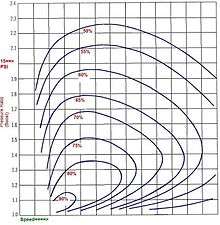

Roots Efficiency map

For any given Roots blower running under given conditions, a single point will fall on the map. This point will rise with increasing boost and will move to the right with increasing blower speed. It can be seen that, at moderate speed and low boost, the efficiency can be over 90%. This is the area in which Roots blowers were originally intended to operate, and they are very good at it.

Boost is given in terms of pressure ratio, which is the ratio of absolute air pressure before the blower to the absolute air pressure after compression by the blower. If no boost is present, the pressure ratio will be 1.0 (meaning 1:1), as the outlet pressure equals the inlet pressure. 15psi boost is marked for reference (slightly above a pressure ratio of 2.0 compared to atmospheric pressure). At 15 psi (1.0 bar) boost, Roots blowers hover between 50% and 58%. Replacing a smaller blower with a larger blower moves the point to the left. In most cases, as the map shows, this will move it into higher efficiency areas on the left as the smaller blower likely will have been running fast on the right of the chart. Usually, using a larger blower and running it slower to achieve the same boost will give an increase in compressor efficiency.

The volumetric efficiency of the Roots-type blower is very good, usually staying above 90% at all but the lowest blower speeds. Because of this, even a blower running at low efficiency will still mechanically deliver the intended volume of air to the engine, but that air will be hotter. In drag racing applications where large volumes of fuel are injected with that hot air, vaporizing the fuel absorbs the heat. This functions as a kind of liquid aftercooler system and goes a long way to negating the inefficiency of the Roots design in that application.

Comparative advantages

Rotary lobe blowers, commonly called boosters in high vacuum application, are not used as a stand-alone pump. In high vacuum applications, the boosters' pumping speed can be used towards reducing the end pressure and increasing the pumping speed.

Related terms

The term "blower" is commonly used to define a device placed on engines with a functional need for additional airflow using a direct mechanical link as its energy source. The term blower is used to describe different types of superchargers. A screw type supercharger, Roots type supercharger, and a centrifugal supercharger are all types of blowers. Conversely, a turbocharger, using exhaust compression to spin its turbine, and not a direct mechanical link, is not generally regarded as a "blower" but simply a "turbo".

See also

- Drag racing, where Roots type superchargers are used forT/F top fuel dragsters, F/C Fuel Coupe funny car each using nitro-methane fuel and T/AD dragsters and TA/FC funny cars using alcohol fuel and Pro Modified using methanol fuel in professional drag racing classes

- TVS Supercharger

References

- (5 April 2002). Roots Type Superchargers Explained. SuperchargersOnline.com. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- Blower Briefing. Tom Henry Racing. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- Eaton TVS Supercharger The Eaton TVS Supercharger. Retrieved 31 March 2008

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roots superchargers. |

- Flash Animation of Roots Pump

- http://www.everestblowers.com/technical-articles/understandin-blowers.pdf

- http://www.pdblowers.com/t17-positive-displacement-blower-calculations.php