Romania

Coordinates: 46°N 25°E / 46°N 25°E

| Romania | |

|---|---|

Location of Romania (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city |

Bucharest 44°25′N 26°06′E / 44.417°N 26.100°E |

| Official languages | Romanian[1] |

| Recognised minority languages[2] | |

| Ethnic groups (2011[3]) |

|

| Demonym | Romanian |

| Government |

Unitary semi-presidential republic |

| Klaus Iohannis | |

| Mihai Tudose | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Formation | |

| 168 BC | |

| 106 | |

| 275 – 10th century | |

• First Romanian polities | 10th century – 1330 |

| 1330 | |

| 1346 | |

| 1570 | |

• First union under Michael the Brave | 1600 |

| 24 January 1859 | |

| 9 May 1877 / 1878b | |

| 14 March 1881 | |

• Great Unionc | 1 December 1918d |

| Area | |

• Total | 238,397 km2 (92,046 sq mi) (83rd) |

• Water (%) | 3 |

| Population | |

• 2015 estimate |

19,511,000 |

• 2011 census | 20,121,641[3] (58th) |

• Density | 84.4/km2 (218.6/sq mi) (117th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $470.312 billion[5] (42nd) |

• Per capita | $23,957 (61st) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $197.004 billion[5] (49th) |

• Per capita | $10,097 (67th) |

| Gini (2013) |

medium |

| HDI (2015) |

very high · 50th |

| Currency | Romanian leu (RON) |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| EEST (UTC+3) | |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (AD) |

| Drives on the | right |

| Calling code | +40 |

| Patron saint | Saint Andrew |

| ISO 3166 code | RO |

| Internet TLD | .roe |

| |

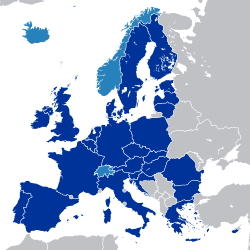

Romania (/roʊˈmeɪniə/ roh-MAY-nee-ə; Romanian: România ![]() i[romɨˈni.a]) is a sovereign state located in Southeastern Europe. It borders the Black Sea, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Hungary, Serbia, and Moldova. It has an area of 238,397 square kilometres (92,046 sq mi) and a temperate-continental climate. With almost 20 million inhabitants, the country is the seventh most populous member state of the European Union. Its capital and largest city, Bucharest, is the sixth-largest city in the EU, with 1,883,425 inhabitants as of 2011.[8]

i[romɨˈni.a]) is a sovereign state located in Southeastern Europe. It borders the Black Sea, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Hungary, Serbia, and Moldova. It has an area of 238,397 square kilometres (92,046 sq mi) and a temperate-continental climate. With almost 20 million inhabitants, the country is the seventh most populous member state of the European Union. Its capital and largest city, Bucharest, is the sixth-largest city in the EU, with 1,883,425 inhabitants as of 2011.[8]

The River Danube, Europe's second-longest river, rises in Germany and flows in a general southeast direction for 2,857 km (1775 mi), coursing through ten countries before emptying into Romania's Danube Delta. The Carpathian Mountains, which cross Romania from the north to the southwest, include Moldoveanu, at 2,544 m (8,346 ft).[9]

Modern Romania was formed in 1859 through a personal union of the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. The new state, officially named Romania since 1866, gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1877. At the end of World War I, Transylvania, Bukovina and Bessarabia united with the sovereign Kingdom of Romania. During World War II, Romania was an ally of Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union, fighting side by side with the Wehrmacht until 1944, when it joined the Allied powers and faced occupation by the Red Army forces. Romania lost several territories, of which Northern Transylvania was regained after the war. Following the war, Romania became a socialist republic and member of the Warsaw Pact. After the 1989 Revolution, Romania began a transition towards democracy and a capitalist market economy.

Romania is a developing country and one of the poorest in the European Union.[10] Following rapid economic growth in the early 2000s, Romania has an economy predominantly based on services, and is a producer and net exporter of machines and electric energy, featuring companies like Automobile Dacia and OMV Petrom. It has been a member of NATO since 2004, and part of the European Union since 2007. A strong majority of the population identify themselves as Eastern Orthodox Christians and are native speakers of Romanian, a Romance language. The cultural history of Romania is often referred to when dealing with influential artists, musicians, inventors and sportspeople.

Etymology

Romania derives from the Latin romanus, meaning "citizen of Rome".[11] The first known use of the appellation was attested in the 16th century by Italian humanists travelling in Transylvania, Moldavia, and Wallachia.[12][13][14][15]

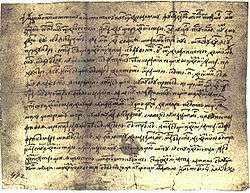

The oldest known surviving document written in Romanian, a 1521 letter known as the "Letter of Neacșu from Câmpulung",[16] is also notable for including the first documented occurrence of the country's name: Wallachia is mentioned as Țeara Rumânească (old spelling for "The Romanian Land"; țeara from the Latin terra, "land"; current spelling: Țara Românească).

Two spelling forms: român and rumân were used interchangeably[lower-alpha 1] until sociolinguistic developments in the late 17th century led to semantic differentiation of the two forms: rumân came to mean "bondsman", while român retained the original ethnolinguistic meaning.[17] After the abolition of serfdom in 1746, the word rumân gradually fell out of use and the spelling stabilised to the form român.[lower-alpha 2] Tudor Vladimirescu, a revolutionary leader of the early 19th century, used the term Rumânia to refer exclusively to the principality of Wallachia."[18]

The use of the name Romania to refer to the common homeland of all Romanians—its modern-day meaning—was first documented in the early 19th century.[lower-alpha 3] The name has been officially in use since 11 December 1861.[19]

In English, the name of the country was formerly spelt Rumania or Roumania.[20] Romania became the predominant spelling around 1975.[21] Romania is also the official English-language spelling used by the Romanian government.[22] A handful of other languages (including Italian, Hungarian, Portuguese, and Norwegian) have also switched to "o" like English, but most languages continue to prefer forms with u, e.g. French Roumanie, German and Swedish Rumänien, Spanish Rumanía, Polish Rumunia, and Russian Румыния (Rumyniya).

Official names

- 1859–1862: United Principalities

- 1862–1866: Romanian United Principalities or Romania

- 1866–1881: Romania

- 1881–1947: Kingdom of Romania or Romania

- 1947–1965: Romanian People's Republic (RPR) or Romania

- 1965–December 1989: Socialist Republic of Romania (RSR) or Romania

- December 1989–present: Romania

History

Early history

.svg.png)

The human remains found in Peștera cu Oase ("The Cave with Bones"), radiocarbon dated as being from circa 40,000 years ago, represent the oldest known Homo sapiens in Europe.[23][24] The Neolithic-Age Cucuteni area in northeastern Romania was the western region of the earliest European civilization, known as the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture.[25] Also the earliest known salt works in the world is at Poiana Slatinei, near the village of Lunca in Romania; it was first used in the early Neolithic, around 6050 BC, by the Starčevo culture, and later by the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in the Pre-Cucuteni period.[26] Evidence from this and other sites indicates that the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture extracted salt from salt-laden spring water through the process of briquetage.

Prior to the Roman conquest of Dacia, the territories between the Danube and Dniester rivers were inhabited by various Thracian peoples, including the Dacians and the Getae.[27] Herodotus, in his work "Histories", notes the religious difference between the Getae and other Thracians,[28] however, according to Strabo, the Dacians and the Getae spoke the same language.[27] Dio Cassius draws attention to the cultural similarities between the two people.[27] There is a scholarly dispute whether the Dacians and the Getae were the same people.[29][30]

Roman incursions under Emperor Trajan between 101–102 AD and 105–106 AD resulted in half of the Dacian kingdom becoming a province of the Roman Empire called "Dacia Felix". The Roman rule lasted for 165 years. During this period the province was fully integrated into the Roman Empire, and a sizeable part of the population were newcomers from other provinces.[31] The Roman colonists introduced the Latin language. According to followers of the continuity theory, the intense Romanization gave birth to the Proto-Romanian language.[32][33] The province was rich in ore deposits (especially gold and silver in places like Alburnus Maior). Roman troops pulled out of Dacia around 271 AD.[34][35] The territory was later invaded by various migrating peoples.[36][37][38][39]

Burebista, Decebalus and Trajan are considered the Romanians' forefathers in Romanian historiography.[40][41][42]

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, Romanians lived in three principalities: Wallachia (Romanian: Țara Românească – "The Romanian Land"), Moldavia (Romanian: Moldova) and in Transylvania.[43] The existence of independent Romanian voivodeships in Transylvania as early as the 9th century is mentioned in Gesta Hungarorum,[44] but by the 11th century, Transylvania had become a largely autonomous part of the Kingdom of Hungary.[45] In the other parts, many small local states with varying degrees of independence developed, but only under Basarab I and Bogdan I the larger principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia would emerge in the 14th century to fight the threat of the Ottoman Empire.[46][47]

By 1541, the entire Balkan peninsula and most of Hungary had been conquered and integrated into the Ottoman Empire. By contrast, Moldavia, Wallachia, and Transylvania, while under Ottoman suzerainty, preserved partial or full internal autonomy until the mid-19th century (Transylvania until 1711[48]). This period featured several prominent rulers such as: Stephen the Great, Vasile Lupu, Alexander the Good and Dimitrie Cantemir in Moldavia; Vlad the Impaler, Mircea the Elder, Matei Basarab, Neagoe Basarab and Constantin Brâncoveanu in Wallachia; and Gabriel Bethlen in the Principality of Transylvania, as well as John Hunyadi and Matthias Corvinus in Transylvania, while it was still a part of the Kingdom of Hungary.[49][50] In 1600, all three principalities were ruled simultaneously by the Wallachian prince Michael the Brave (Mihai Viteazul), who was considered, later on, the precursor of modern Romania and became a point of reference for nationalists, as well as a catalyst for achieving a single Romanian state.[51]

Independence and monarchy

During the period of the Austro-Hungarian rule in Transylvania and of Ottoman suzerainty over Wallachia and Moldavia, most Romanians were given few rights[52] in a territory where they formed the majority of the population.[53][54] Nationalistic themes became principal during the Wallachian uprising of 1821, and the 1848 revolutions in Wallachia and Moldavia. The flag adopted for Wallachia by the revolutionaries was a blue-yellow-red horizontal tricolour (with blue above, in line with the meaning "Liberty, Justice, Fraternity"),[55] while Romanian students in Paris hailed the new government with the same flag "as a symbol of union between Moldavians and Wallachians".[56][57] The same flag, with the tricolour being mounted vertically, would later be officially adopted as the national flag of Romania.[58]

After the failed 1848 revolutions not all the Great Powers supported the Romanians' expressed desire to officially unite in a single state.[59] But in the aftermath of the Crimean War, the electors in both Moldavia and Wallachia voted in 1859 for the same leader, Alexandru Ioan Cuza, as Domnitor ("ruling prince" in Romanian), and the two principalities became a personal union formally under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire.[60] Following a coup d'état in 1866, Cuza was exiled and replaced with Prince Carol I of Romania of the House of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. During the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War Romania fought on the Russian side,[61] and in the aftermath, it was recognized as an independent state both by the Ottoman Empire and the Great Powers by the Treaty of San Stefano and the Treaty of Berlin.[62][63] The new Kingdom of Romania underwent a period of stability and progress until 1914, and also acquired Southern Dobruja from Bulgaria after the Second Balkan War.[64]

World Wars and Greater Romania

Romania remained neutral for the first two years of World War I. Following the secret Treaty of Bucharest, according to which Romania would acquire territories with a majority of Romanian population from Austria-Hungary, it joined the Entente Powers and declared war on 27 August 1916.[65] After initial advances the Romanian military campaign quickly turned disastrous for Romania as the Central Powers occupied two-thirds of the country within months, before reaching a stalemate in 1917. The October Revolution and Russian withdrawal from the War left Romania alone and surrounded, and a cease fire was negotiated at Focșani that December. Romania was occupied and a harsh peace treaty was signed in May 1918. In November, Romania reentered the conflict. Total military and civilian losses from 1916 to 1918, within contemporary borders, were estimated at 748,000.[66] After the war, the transfer of Bukovina from Austria was acknowledged by the 1919 Treaty of Saint Germain,[67] of Banat and Transylvania from Hungary by the 1920 Treaty of Trianon,[68] and of Bessarabia from Russian rule by the 1920 Treaty of Paris.[69] All cessations made to the Central Powers in the ceasefire and treaty were nullified and renounced.[70]

The following interwar period is referred as Greater Romania, as the country achieved its greatest territorial extent at that time (almost 300,000 km2 or 120,000 sq mi).[71] The application of radical agricultural reforms and the passing of a new constitution created a democratic framework and allowed for quick economic growth. With oil production of 7.2 million tons in 1937, Romania ranked second in Europe and seventh in the world.[72][73] and was Europe's second-largest food producer.[74] However, the early 1930s were marked by social unrest, high unemployment, and strikes, as there were over 25 separate governments throughout the decade. On several occasions in the last few years before World War II, the democratic parties were squeezed between conflicts with the fascist and chauvinistic Iron Guard and the authoritarian tendencies of King Carol II.[75]

During World War II, Romania tried again to remain neutral, but on 28 June 1940, it received a Soviet ultimatum with an implied threat of invasion in the event of non-compliance.[76] Again foreign powers created heavy pressure on Romania, by means of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of non-aggression from 23 August 1939. As a result of it the Romanian government and the army were forced to retreat from Bessarabia as well as from northern Bukovina in order to avoid war with the Soviet Union.[77] The king was compelled to abdicate and appointed general Ion Antonescu as the new Prime Minister with full powers in ruling the state by royal decree.[78] Romania was prompted to join the Axis military campaign. Thereafter, southern Dobruja was ceded to Bulgaria, while Hungary received Northern Transylvania as result of an Axis powers' arbitration.[79]

The Antonescu fascist regime played a major role in The Holocaust in Romania,[80] and copied the Nazi policies of oppression and genocide of Jews and Roma, mainly in the Eastern territories reoccupied by the Romanians from the Soviet Union. In total between 280,000 and 380,000 Jews in Romania (including Bessarabia, Bukovina and the Transnistria Governorate) were killed during the war[81][82] and at least 11,000 Romanian Gypsies ("Roma") were also killed.[83] In August 1944, a coup d'état led by King Michael toppled Ion Antonescu and his regime. Antonescu was convicted of war crimes and executed on 1 June 1946.[84] 9 October is now the National Day of Commemorating the Holocaust in Romania.[85]

During the Antonescu fascist regime, Romanian contribution to Operation Barbarossa was enormous, with the Romanian Army of over 1.2 million men in the summer of 1941, fighting in numbers second only to Nazi Germany.[86] Romania was the main source of oil for the Third Reich,[87] and thus became the target of intense bombing by the Allies. Growing discontent among the population eventually peaked in August 1944 with King Michael's Coup, and the country switched sides to join the Allies. It is estimated that the coup shortened the war by as much as six months.[88] Even though the Romanian Army had suffered 170,000 casualties after switching sides,[89] Romania's role in the defeat of Nazi Germany was not recognized by the Paris Peace Conference of 1947,[90] as the Soviet Union annexed Bessarabia and other territories corresponding roughly to present-day Republic of Moldova, and Bulgaria retained Southern Dobruja, but Romania did regain Northern Transylvania from Hungary.

Communism

During the Soviet occupation of Romania, the Communist-dominated government called for new elections in 1946, which were fraudulently won, with a fabricated 70% majority of the vote.[91] Thus they rapidly established themselves as the dominant political force.[92] Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, a Communist party leader imprisoned in 1933, escaped in 1944 to become Romania's first Communist leader. In 1947 he and others forced King Michael I to abdicate and leave the country, and proclaimed Romania a people's republic.[93][94] Romania remained under the direct military occupation and economic control of the USSR until the late 1950s. During this period, Romania's vast natural resources were continuously drained by mixed Soviet-Romanian companies (SovRoms) set up for unilateral exploitative purposes.[95][96][97]

In 1948, the state began to nationalize private firms and to collectivize agriculture.[98] Until the early 1960s, the government severely curtailed political liberties and vigorously suppressed any dissent with the help of the Securitate (the Romanian secret police). During this period the regime launched several campaigns of purges in which numerous "enemies of the state" and "parasite elements" were targeted for different forms of punishment, such as deportation, internal exile and internment in forced labour camps and prisons, sometimes for life, as well as extrajudicial killing.[99] Nevertheless, anti-Communist resistance was one of the most long-lasting in the Eastern Bloc.[100] A 2006 Commission estimated the number of direct victims of the Communist repression at two million people.[101]

In 1965, Nicolae Ceaușescu came to power and started to conduct the foreign policy more independently from the Soviet Union. Thus, Communist Romania was the only Warsaw Pact country who refused to participate at the Soviet-led 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia (Ceaușescu even publicly condemned the action as "a big mistake, [and] a serious danger to peace in Europe and to the fate of Communism in the world"[102]); it was also the only Communist state to maintain diplomatic relations with Israel after 1967's Six-Day War; and established diplomatic relations with West Germany the same year.[103] At the same time, close ties with the Arab countries (and the PLO) allowed Romania to play a key role in the Israel–Egypt and Israel–PLO peace talks.[104]

As Romania's foreign debt sharply increased between 1977 and 1981 (from US$3 billion to $10 billion),[105] the influence of international financial organizations (such as the IMF and the World Bank) grew, gradually conflicting with Ceaușescu's autocratic rule. The latter eventually initiated a policy of total reimbursement of the foreign debt by imposing austerity steps that impoverished the population and exhausted the economy. The process succeeded in repaying all foreign government debt of Romania in 1989. At the same time, Ceaușescu greatly extended the authority of the Securitate secret police and imposed a severe cult of personality, which led to a dramatic decrease in the dictator's popularity and culminated in his overthrow and eventual execution, together with his wife, in the violent Romanian Revolution of December 1989 in which thousands were killed or injured. The charges for which they were executed were, among others, genocide by starvation.

Contemporary period

After the 1989 revolution, the National Salvation Front (NSF), led by Ion Iliescu, took partial multi-party democratic and free market measures.[106][107] In April 1990, a sit-in protest contesting the results of the elections and accusing the NSF, including Iliescu, of being made up of former Communists and members of the Securitate — rapidly grew to become what was called the Golaniad. The peaceful demonstrations degenerated into violence, prompting the intervention of coal miners summoned by Iliescu. This episode has been documented widely by both local[108] and foreign media,[109] and is remembered as the June 1990 Mineriad.[110][111]

The subsequent disintegration of the Front produced several political parties, including the Social Democratic Party and the Democratic Party. The former governed Romania from 1990 until 1996 through several coalitions and governments with Ion Iliescu as head of state. Since then, there have been several other democratic changes of government: in 1996 Emil Constantinescu was elected president, in 2000 Iliescu returned to power, while Traian Băsescu was elected in 2004 and was narrowly re-elected in 2009.[112] In November 2014, Sibiu mayor Klaus Iohannis was elected president, unexpectedly defeating Prime Minister Victor Ponta, who had been in the lead in the opinion polls. This surprise victory is attributed by many to the Romanian diaspora, of which almost 50 percent voted for Iohannis in the first tour, compared to 16 percent for Ponta.[113]

Former President Traian Basescu (2004–2014) has twice been impeached by the Parliament of Romania (in 2007 and in 2012), the second time on the background of street protest earlier in the year. Both times a popular referendum was called. The second time, in the Romanian presidential impeachment referendum, 2012, more than 7 million voters (88% of participants)[114] voted to oust Basescu, compared to the 5.2 million voters who initially supported him in the Romanian presidential election, 2009. However the Constitutional Court of Romania, in a split decision, invalided the outcome of the referendum, stating the turnout (46.24% by official statistics) was too low.[115] Supporters of Basescu were called upon by him and his former party to not participate in the referendum, so that it would be invalidated due to insufficient turnout.[116]

The post-1989 period is also characterized by the fact that most of the former industrial and economic enterprises which were built and operated during the Communist period have been closed, mainly as a result of the policies of privatization of the post-1989 regimes.[117] According to Valentin Mândrăşescu, a Romanian-language editor of the Voice of Russia, the national petroleum company Petrom has been sold to foreigners for significantly undervalued prices.[118][119] Furthermore, other major privatizations like that of Banca Comerciala a Romaniei are criticized by opponents for being detrimental to the Romanian people.[120]

Post-1989 regimes are also criticized for allowing foreign exploitations of mineral, rare metals and gold reserves at Rosia Montana,[121] as well as for permitting American multinational energy giant Chevron to prospect for shale gas using the hydraulic fracking technique which has been claimed to pollute the vast underground freshwater reserves in the affected areas. Both these actions have led to significant protests by the population in 2012–2014. In November 2015, Romania's prime minister Victor Ponta resigned as massive anti-corruption protests developed in the wake of the Colectiv nightclub fire.[122]

NATO and EU integration

After the end of the Cold War, Romania developed closer ties with Western Europe and the United States, eventually joining NATO in 2004, and hosting the 2008 summit in Bucharest.[123]

.jpg)

The country applied in June 1993 for membership in the European Union and became an Associated State of the EU in 1995, an Acceding Country in 2004, and a full member on 1 January 2007.[124]

During the 2000s, Romania enjoyed one of the highest economic growth rates in Europe and has been referred at times as "the Tiger of Eastern Europe".[125] This has been accompanied by a significant improvement in living standards as the country successfully reduced internal poverty and established a functional democratic state.[126][127] However, Romania's development suffered a major setback during the late-2000s recession leading to a large gross domestic product contraction and budget deficit in 2009.[128] This led to Romania borrowing from the International Monetary Fund.[129] The worsening economic conditions led to unrest and triggered a political crisis in 2012.[130]

Romania still faces problems related to infrastructure,[131] medical services,[132] education,[133] and corruption.[134] Near the end of 2013, The Economist reported Romania again enjoying 'booming' economic growth at 4.1% that year, with wages rising fast and a lower unemployment than in Britain. Economic growth accelerated in the midst of government liberalisations in opening up new sectors to competition and investment—most notably, energy and telecoms.[135] In 2016 the Human Development Index ranked Romania as a nation of "Very High Human Development".[136]

Following the experience of economic instability throughout the 1990s, and the implementation of a free travel agreement with the EU, a great number of Romanians emigrated to Western Europe and North America, with particularly large communities in Italy and Spain. In 2008, the Romanian diaspora was estimated to be at over two million people.[137] The cyclical nature of the world economy and economic disparities between Romania and advanced European economies has fueled further emigration from the country. The emigration has caused social changes in Romania, whereby the parents would leave for Western Europe to escape poverty and provide a better standard of living for their children, who have been left behind. Some children are left to be taken care of by grandparents and relatives; and some live alone, if the parents deem them to be reasonably self-sufficient.[138] Subsequently, the youth began to be called Euro-orphans.[139]

Geography and climate

With an area of 238,391 square kilometres (92,043 sq mi), Romania is the largest country in Southeastern Europe and the twelfth-largest in Europe.[140] It lies between latitudes 43° and 49° N, and longitudes 20° and 30° E.

The terrain is distributed roughly equally between mountains, hills and plains.

The Carpathian Mountains dominate the centre of Romania, with 14 mountain ranges reaching above 2,000 m or 6,600 ft, and the highest point at Moldoveanu Peak (2,544 m or 8,346 ft, pictured right).[140] They are surrounded by the Moldavian and Transylvanian plateaus and Carpathian Basin and Wallachian plains.

47% of the country's land area is covered with natural and semi-natural ecosystems.[141] There are almost 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi) (about 5% of the total area) of protected areas in Romania covering 13 national parks and three biosphere reserves.[142]

The Danube river forms a large part of the border with Serbia and Bulgaria, and flows into the Black Sea, forming the Danube Delta, which is the second-largest and best-preserved delta in Europe, and also a biosphere reserve and a biodiversity World Heritage Site.[143] At 5,800 km2 (2,200 sq mi),[144] the Danube Delta is the largest continuous marshland in Europe,[145] and supports 1,688 different plant species alone.[146]

Romania has one of the largest areas of undisturbed forest in Europe, covering almost 27% of the territory.[147] Some 3,700 plant species have been identified in the country, from which to date 23 have been declared natural monuments, 74 missing, 39 endangered, 171 vulnerable and 1,253 rare.[148]

The fauna consists of 33,792 species of animals, 33,085 invertebrate and 707 vertebrate,[148] with almost 400 unique species of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians,[149] including about 50% of Europe's (excluding Russia) brown bears[150] and 20% of its wolves.[151]

Climate

Owing to its distance from open sea and position on the southeastern portion of the European continent, Romania has a climate that is temperate and continental, with four distinct seasons. The average annual temperature is 11 °C (52 °F) in the south and 8 °C (46 °F) in the north.[152] In summer, average maximum temperatures in Bucharest rise to 28 °C (82 °F), and temperatures over 35 °C (95 °F) are fairly common in the lower-lying areas of the country.[153] In winter, the average maximum temperature is below 2 °C (36 °F).[153] Precipitation is average, with over 750 mm (30 in) per year only on the highest western mountains, while around Bucharest it drops to around 600 mm (24 in).[154] There are some regional differences: in the western parts (such as Banat), the climate is milder, and has some Mediterranean influences; while the eastern part of the country has a more pronounced continental climate. In Dobruja, the Black Sea also exerts an influence over the region's climate.[155]

| Location | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bucharest | 28.8/15.6 | 84/60 | 1.5/−5.5 | 35/22 |

| Cluj-Napoca | 24.5/12.7 | 76/55 | 0.3/−6.5 | 33/20 |

| Timișoara | 27.8/14.6 | 82/58 | 2.3/−4.8 | 36/23 |

| Iași | 26.8/15 | 80/59 | −0.1/−6.9 | 32/20 |

| Constanța | 25.9/18 | 79/64 | 3.7/−2.3 | 39/28 |

| Craiova | 28.5/15.7 | 83/60 | 1.5/−5.6 | 35/22 |

| Brașov | 24.2/11.4 | 76/53 | −0.1/−9.3 | 32/15 |

| Galați | 27.9/16.2 | 82/61 | 1.1/–5.3 | 34/22 |

Governance

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Romania |

|

The Constitution of Romania is based on the Constitution of France's Fifth Republic and was approved in a national referendum on 8 December 1991, and amended in October 2003 to bring it into conformity with the EU legislation. The country is governed on the basis of a multi-party democratic system and the separation of powers between the legislative, executive and judicial branches. It is a semi-presidential republic where executive functions are held by both government and the president.[157] The latter is elected by popular vote for a maximum of two terms of five years and appoints the prime minister, who in turn appoints the Council of Ministers. The legislative branch of the government, collectively known as the Parliament (residing at the Palace of the Parliament), consists of two chambers (Senate and Chamber of Deputies) whose members are elected every four years by simple plurality.[158][159]

The justice system is independent of the other branches of government, and is made up of a hierarchical system of courts culminating in the High Court of Cassation and Justice, which is the supreme court of Romania.[160] There are also courts of appeal, county courts and local courts. The Romanian judicial system is strongly influenced by the French model, considering that it is based on civil law and is inquisitorial in nature. The Constitutional Court (Curtea Constituțională) is responsible for judging the compliance of laws and other state regulations to the constitution, which is the fundamental law of the country and can only be amended through a public referendum.[158][161] The 2007 entry into the EU has been a significant influence on its domestic policy, and including judicial reforms, increased judicial cooperation with other member states, and measures to combat corruption.

Foreign relations

Since December 1989, Romania has pursued a policy of strengthening relations with the West in general, more specifically with the United States and the European Union albeit with its limited relations with Russia. It joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on 29 March 2004, the European Union (EU) on 1 January 2007, while it had joined the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank in 1972, and is a founding member of the World Trade Organization.[162]

The current government has stated its goal of strengthening ties with and helping other countries (in particular Moldova, Ukraine and Georgia) with the process of integration with the rest of the West.[163] Romania has also made clear since the late 1990s that it supports NATO and EU membership for the democratic former Soviet republics in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus.[163] Romania also declared its public support for Turkey, and Croatia joining the European Union.[163] Because it has a large Hungarian minority, Romania has also developed strong relations with Hungary. Romania opted on 1 January 2007, to adhere the Schengen Area, and its bid to join was approved by the European Parliament in June 2011, but was rejected by the EU Council in September 2011.

In December 2005, President Traian Băsescu and United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice signed an agreement that would allow a U.S. military presence at several Romanian facilities primarily in the eastern part of the country.[164] In May 2009, Hillary Clinton, US Secretary of State, declared that "Romania is one of the most trustworthy and respectable partners of the USA."[165]

Relations with Moldova are a special case, considering that the two countries share the same language and a common history.[163] A movement for unification of Romania and Moldova appeared in the early 1990s after both countries achieved emancipation from communist rule,[166] but lost ground in the mid-1990s when a new Moldovan government pursued an agenda towards preserving a Moldovan republic independent of Romania.[167] After the 2009 protests in Moldova and subsequent removal of Communists from power, relations between the two countries have improved considerably.[168]

Military

The Romanian Armed Forces consist of Land, Air, and Naval Forces, and are led by a Commander-in-chief under the supervision of the Ministry of Defense, and by the president as the Supreme Commander during wartime. The Armed Forces consist of approximately 15,000 civilians and 75,000 are military personnel—45,800 for land, 13,250 for air, 6,800 for naval forces, and 8,800 in other fields.[169] The total defence spending in 2007 accounted for 2.05% of total national GDP, or approximately US$2.9 billion, with a total of $11 billion spent between 2006 and 2011 for modernization and acquisition of new equipment.[170]

The Air Force currently operates modernized Soviet MiG-21 Lancer fighters which are due to be replaced by twelve F-16s, recently purchased.[171] The Air Force purchased seven new C-27J Spartan tactical airlifters,[172] while the Naval Forces acquired two modernized Type 22 frigates from the British Royal Navy.[173]

Romania has contributed troops to the international coalition in Afghanistan since 2002,[174] with a peak deployment of 1,600 troops in 2010.[175] Its combat mission in the country concluded in 2014.[176] Romanian troops participated in the occupation of Iraq, reaching a peak of 730 soldiers before being slowly drawn down to 350 soldiers. Romania terminated its mission in Iraq and withdrew its last troops on 24 July 2009, among the last countries to do so. The Regele Ferdinand frigate participated in the 2011 military intervention in Libya.[177]

In December 2011, the Romanian Senate unanimously adopted the draft law ratifying the Romania-United States agreement signed in September of the same year that would allow the establishment and operation of a US land-based ballistic missile defence system in Romania as part of NATO's efforts to build a continental missile shield.[178]

Administrative divisions

Romania is divided into 41 counties (județe, pronounced judets) and the municipality of Bucharest. Each county is administered by a county council, responsible for local affairs, as well as a prefect responsible for the administration of national affairs at the county level. The prefect is appointed by the central government but cannot be a member of any political party.[179] Each county is further subdivided into cities and communes, which have their own mayor and local council. There are a total of 319 cities and 2,686 communes in Romania.[180] A total of 103 of the larger cities have municipality statuses, which gives them greater administrative power over local affairs. The municipality of Bucharest is a special case as it enjoys a status on par to that of a county. It is further divided into six sectors and has a prefect, a general mayor (primar), and a general city council.[180]

The NUTS-3 (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) level divisions of European Union reflect Romania's administrative-territorial structure, and correspond to the 41 counties plus Bucharest.[181] The cities and communes correspond to the NUTS-5 level divisions, but there are no current NUTS-4 level divisions. The NUTS-1 (four macroregions) and NUTS-2[182] (eight development regions) divisions exist but have no administrative capacity, and are instead used for coordinating regional development projects and statistical purposes.[181]

| Development region | Area (km2) | Population (2011)[183] | Most populous urban center*[184] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nord-Vest | 34,159 | 2,600,132 | Cluj-Napoca (411,379) |

| Centru | 34,082 | 2,360,805 | Brașov (369,896) |

| Nord-Est | 36,850 | 3,302,217 | Iași (382,484) |

| Sud-Est | 35,762 | 2,545,923 | Constanța (425,916) |

| Sud – Muntenia | 34,489 | 3,136,446 | Ploiești (276,279) |

| București – Ilfov | 1,811 | 2,272,163 | Bucharest (2,272,163) |

| Sud-Vest Oltenia | 29,212 | 2,075,642 | Craiova (356,544) |

| Vest | 32,028 | 1,828,313 | Timișoara (384,809) |

Economy

In 2016, Romania had a GDP (PPP) of around $441.601 billion and a GDP per capita (PPP) of $22,348.[185] According to the World Bank, Romania is an upper-middle income country economy.[186] According to Eurostat, Romania's GDP per capita (PPS) was at 59% of the EU average in 2016, an increase from 41% in 2007 (the year of Romania's accession to the EU), making Romania one of the fastest growing economies in the EU.[187]

After 1989 the country experienced a decade of economic instability and decline, led in part by an obsolete industrial base and a lack of structural reform. From 2000 onward, however, the Romanian economy was transformed into one of relative macroeconomic stability, characterized by high growth, low unemployment and declining inflation. In 2006, according to the Romanian Statistics Office, GDP growth in real terms was recorded at 7.7%, one of the highest rates in Europe.[188] However, a recession following the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 forced the government to borrow externally, including an IMF €20bn bailout program.[189] GDP has been growing by over 2% each year since.[190] According to The World Bank, the GDP per capita purchasing power parity grew from $13,442 in 2007 to an estimated $22,124 in 2015.[191] Romania still has one of the lowest net average monthly wage in the EU of €540 in 2016,[192] and an inflation of −1.1% in 2016.[193] Unemployment in Romania is at 5.4% in 2017, which is very low compared to other EU countries.[191]

Industrial output growth reached 6.5% year-on-year in February 2013, the highest in the EU-27.[194] The largest local companies include car maker Automobile Dacia, Petrom, Rompetrol, Ford Romania, Electrica, Romgaz, RCS & RDS and Banca Transilvania.[195] Exports have increased substantially in the past few years, with a 13% annual rise in exports in 2010. Romania's main exports are cars, software, clothing and textiles, industrial machinery, electrical and electronic equipment, metallurgic products, raw materials, military equipment, pharmaceuticals, fine chemicals, and agricultural products (fruits, vegetables, and flowers). Trade is mostly centered on the member states of the European Union, with Germany and Italy being the country's single largest trading partners. The account balance in 2012 was estimated to be −4.52% of the GDP.[196]

After a series of privatizations and reforms in the late 1990s and 2000s, government intervention in the Romanian economy is somewhat lower than in other European economies.[197] In 2005, the government replaced Romania's progressive tax system with a flat tax of 16% for both personal income and corporate profit, among the lowest rates in the European Union.[198] The economy is predominantly based on services, which account for 51% of GDP, even though industry and agriculture also have significant contributions, making up 36% and 13% of GDP, respectively. Additionally, 30% of the Romanian population was employed in 2006 in agriculture and primary production, one of the highest rates in Europe.[199]

Since 2000, Romania has attracted increasing amounts of foreign investment, becoming the single largest investment destination in Southeastern and Central Europe. Foreign direct investment was valued at €8.3 billion in 2006.[200] According to a 2011 World Bank report, Romania currently ranks 72nd out of 175 economies in the ease of doing business, scoring lower than other countries in the region such as the Czech Republic.[201] Additionally, a study in 2006 judged it to be the world's second-fastest economic reformer (after Georgia).[202]

Since 1867 the official currency has been the Romanian leu ("lion") and following a denomination in 2005, it has been valued at €0.2–0.3. After joining the EU in 2007, Romania is expected to adopt the euro sometime around 2020.[203]

At 1 July 2015, Romanian's external debt was €90.59 billion.[204]

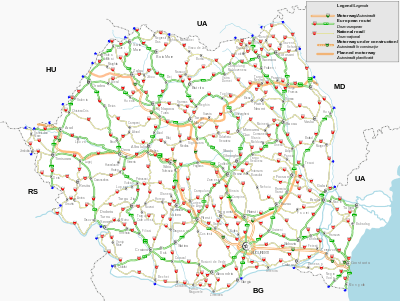

Infrastructure

According to the INSSE, Romania's total road network was estimated in 2015 at 86,080 kilometres (53,488 mi).[205] The World Bank estimates the railway network at 22,298 kilometres (13,855 mi) of track, the fourth-largest railroad network in Europe.[206] Rail transport experienced a dramatic decline after 1989, and was estimated at 99 million passenger journeys in 2004; but has experienced a recent (2013) revival due to infrastructure improvements and partial privatization of lines,[158] accounting for 45% of all passenger and freight movements in the country.[158] Bucharest Metro, the only underground railway system, was opened in 1979 and measures 61.41 km (38.16 mi) with an average ridership in 2007 of 600,000 passengers during the workweek.[207] There are sixteen international commercial airports in service today, with five of them (Henri Coandă International Airport, Aurel Vlaicu International Airport, Timișoara International Airport, Constanta International Airport and Sibiu International Airport) being capable of handling wide-body aircraft. Over 9.2 million passengers flew through Bucharest's Henri Coandă International Airport in 2015.[208]

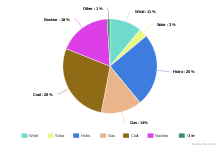

Romania is a net exporter of electrical energy and is 48th worldwide in terms of consumption of electric energy.[209] Around a third of the produced energy comes from renewable sources, mostly as hydroelectric power.[210] In 2015, the main sources were coal (28%), hydroelectric (30%), nuclear (18%), and hydrocarbons (14%) .[211] It has one of the largest refining capacities in Eastern Europe, even though oil and natural gas production has been decreasing for more than a decade.[209] With one of the largest reserves of crude oil and shale gas in Europe,[209] it is among the most energy-independent countries in the European Union,[212] and is looking to further expand its nuclear power plant at Cernavodă.[213]

There were almost 18,3 million connections to the Internet in June 2014.[214] According to Bloomberg, in 2013 Romania ranked 5th in the world, and according to The Independent, it ranks number one in Europe at internet speeds,[215][216] with Timișoara ranked among the highest in the world.[217]

Tourism

Tourism is a significant contributor to the Romanian economy, generating around 5% of GDP.[218] According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, Romania was estimated to have the fourth-fastest-growing travel and tourism total demand in the world, with an estimated potential growth of 8% per year from 2007 to 2016.[219] The number of tourists has been steadily rising, reaching 3.5 million in the first half of 2014.[220] Tourism in Romania attracted €400 million in investments in 2005.[221]

More than 60% of the foreign visitors in 2007 were from other EU countries.[222] The popular summer attractions of Mamaia and other Black Sea Resorts attracted 1.3 million tourists in 2009.[223][224] Most popular skiing resorts are along the Valea Prahovei and in Poiana Brașov. Castles in Transylvanian cities such as Sibiu, Brașov, and Sighișoara also attract a large number of tourists. Bran Castle, near Brașov, is one of the most famous attractions in Romania, drawing hundreds of thousands of tourists every year as it is often advertised as being Dracula's Castle.[225]

Rural tourism, focusing on folklore and traditions, has become an important alternative,[226] and is targeted to promote such sites as Bran and its Dracula's Castle, the Painted churches of Northern Moldavia, and the Wooden churches of Maramureș.[227] Other attractions include the Danube Delta, and the Sculptural Ensemble of Constantin Brâncuși at Târgu Jiu.[228][229]

In 2014, Romania had 32,500 companies which were active in the hotel and restaurant industry, with a total turnover of EUR 2.6 billion.[230] More than 1.9 million foreign tourists visited Romania in 2014, 12% more than in 2013.[231] According to the country's National Statistics Institute, some 77% came from Europe (particularly from Germany, Italy and France), 12% from Asia, and less than 7% from North America.[231]

Science and technology

Historically, Romanian researchers and inventors have made notable contributions to several fields. In the history of flight, Traian Vuia made the first airplane to take off on its own power[232] and Aurel Vlaicu built and flew some of the earliest successful aircraft, while Henri Coandă discovered the Coandă effect of fluidics. Victor Babeș discovered more than 50 types of bacteria; biologist Nicolae Paulescu discovered insulin, while Emil Palade, received the Nobel Prize for his contributions to cell biology. Lazăr Edeleanu was the first chemist to synthesize amphetamine and he also invented the procedure of separating valuable petroleum components with selective solvents, while Costin Nenițescu developed numerous new classes of compounds in organic chemistry. Notable mathematicians include Spiru Haret, Grigore Moisil, and Ștefan Odobleja; physicists and inventors: Șerban Țițeica, Alexandru Proca, and Ștefan Procopiu.

During the 1990s and 2000s, the development of research was hampered by several factors, including corruption, low funding and a considerable brain drain.[233] However, since the country's accession to the European Union, this has begun to change.[234] After being slashed by 50% in 2009 because of the global recession, R&D spending was increased by 44% in 2010 and now stands at $0.5 billion (1.5 billion lei).[235] In January 2011, the Parliament also passed a law that enforces "strict quality control on universities and introduces tough rules for funding evaluation and peer review".[236] The country has joined or is about to join several major international organizations such as CERN and the European Space Agency.[237][238] Overall, the situation has been characterized as "rapidly improving", albeit from a low base.[239]

The nuclear physics facility of the European Union's proposed Extreme Light Infrastructure (ELI) laser will be built in Romania.[240] In early 2012, Romania launched its first satellite from the Centre Spatial Guyanais in French Guyana.[241] Starting December 2014, Romania is a co-owner of the International Space Station.[242]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1866 | 4,424,961 | — |

| 1887 | 5,500,000 | +24.3% |

| 1899 | 5,956,690 | +8.3% |

| 1912 | 7,234,919 | +21.5% |

| 1930 | 18,057,028 | +149.6% |

| 1939 | 19,934,000 | +10.4% |

| 1941 | 13,535,757 | −32.1% |

| 1948 | 15,872,624 | +17.3% |

| 1956 | 17,489,450 | +10.2% |

| 1966 | 19,103,163 | +9.2% |

| 1977 | 21,559,910 | +12.9% |

| 1992 | 22,760,449 | +5.6% |

| 2002 | 21,680,974 | −4.7% |

| 2011 | 20,121,641 | −7.2% |

| 2016 (est.) | 19,474,952 | −3.2% |

| Figures prior to 1948 do not reflect current borders. | ||

According to the 2011 census, Romania's population is 20,121,641.[3] Like other countries in the region, its population is expected to gradually decline in the coming years as a result of sub-replacement fertility rates and negative net migration rate. In October 2011, Romanians made up 88.9% of the population. The largest ethnic minorities are the Hungarians, 6.1% of the population, and the Roma, 3.0% of the population.[lower-alpha 4][243] Hungarians constitute a majority in the counties of Harghita and Covasna. Other minorities include Ukrainians, Germans, Turks, Lipovans, Aromanians, Tatars, and Serbs.[244] In 1930, there were 745,421 Germans in Romania,[245] but only about 36,000 remain today.[244] As of 2009, there were also approximately 133,000 immigrants living in Romania, primarily from Moldova and China.[126]

The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2015 was estimated at 1.33 children born per woman, which is below the replacement rate of 2.1, and one of the lowest in the world.[246] In 2014, 31.2% of births were to unmarried women.[247] The birth rate (9.49‰, 2012) is much lower than the mortality rate (11.84‰, 2012), resulting in a shrinking (−0.26% per year, 2012) and aging population (median age: 39.1, 2012), with approximately 14.9% of total population aged 65 years and over.[248][249][250] The life expectancy in 2015 was estimated at 74.92 years (71.46 years male, 78.59 years female).[246]

The number of Romanians and individuals with ancestors born in Romania living abroad is estimated at around 12 million.[137] After the Romanian Revolution of 1989, a significant number of Romanians emigrated to other European countries, North America or Australia.[251] For example, in 1990, 96,919 Romanians permanently settled abroad.[252]

Languages

The official language is Romanian, an Eastern Romance language similar to Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian, but sharing many features with other Romance languages such as Italian, French, Spanish and Portuguese. (The Romanian alphabet contains the same 26 letters of the Latin, plus 5 others, totaling 31.) Romanian is spoken as a first language by 85% of the population, while Hungarian and Vlax Romani are spoken by 6.2% and 1.2% of the population, respectively. There are 25,000 native German speakers, and 32,000 Turkish speakers in Romania, as well as almost 50,000 speakers of Ukrainian,[253] concentrated in some compact regions, near the border, where they form a majority.[254] According to the Constitution, local councils ensure linguistic rights to all minorities, with localities with ethnic minorities of over 20%, that minority's language can be used in the public administration, justice system, and education. Foreign citizens and stateless persons that live in Romania have access to justice and education in their own language.[255] English and French are the main foreign languages taught in schools.[256] In 2010, the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie identifies 4,756,100 French speakers in the country.[257] According to the 2012 Eurobarometer, English is spoken by 31% of Romanians, French is spoken by 17%, and Italian by 7%.[258]

Religion

Romania is a secular state and has no state religion. An overwhelming majority of the population identify themselves as Christians. At the country's 2011 census, 81.0% of respondents identified as Orthodox Christians belonging to the Romanian Orthodox Church. Other denominations include Protestantism (6.2%), Roman Catholicism (4.3%), and Greek Catholicism (0.8%). From the remaining population, 195,569 people belong to other Christian denominations or have another religion, which includes 64,337 Muslims (mostly of Turkish and Tatar ethnicity) and 3,519 Jewish. Moreover, 39,660 people have no religion or are atheist, whilst the religion of the rest is unknown.[259]

The Romanian Orthodox Church is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church in full communion with other Orthodox churches, with a Patriarch as its leader. It is the second-largest Orthodox Church in the world, and unlike other Orthodox churches, it functions within a Latin culture and utilizes a Romance liturgical language.[260] Its canonical jurisdiction covers the territories of Romania and Moldova,[261] with dioceses for Romanians living in nearby Serbia and Hungary, as well as diaspora communities in Central and Western Europe, North America and Oceania.

Urbanization

Although 54.0% of the population lived in 2011 in urban areas,[3] this percentage has been on the decline since 1996.[262] Counties with over ⅔ urban population are Hunedoara, Brașov and Constanța, while with less than a third are Dâmbovița (30.06%) and Giurgiu and Teleorman.[3] Bucharest is the capital and the largest city in Romania, with a population of over 1.8 million in 2011. Its larger urban zone has a population of almost 2.2 million,[263] which are planned to be included into a metropolitan area up to 20 times the area of the city proper.[264][265][266] Another 19 cities have a population of over 100,000, with Cluj-Napoca and Timișoara of slightly more than 300,000 inhabitants, Iași, Constanța, Craiova and Brașov with over 250,000 inhabitants, and Galați and Ploiești with over 200,000 inhabitants.[184] Metropolitan areas have been constituted for most of these cities.

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

Bucharest  Cluj-Napoca |

1 | Bucharest | Bucharest | 1,883,425 | 11 | Brăila | Brăila | 180,302 |  Timișoara  Iași |

| 2 | Cluj-Napoca | Cluj | 324,576 | 12 | Arad | Arad | 159,704 | ||

| 3 | Timișoara | Timiș | 319,279 | 13 | Pitești | Argeș | 155,383 | ||

| 4 | Iași | Iași | 290,422 | 14 | Sibiu | Sibiu | 147,245 | ||

| 5 | Constanța | Constanța | 283,872 | 15 | Bacău | Bacău | 144,307 | ||

| 6 | Craiova | Dolj | 269,506 | 16 | Târgu Mureș | Mureș | 134,290 | ||

| 7 | Brașov | Brașov | 253,200 | 17 | Baia Mare | Maramureș | 123,738 | ||

| 8 | Galați | Galați | 249,342 | 18 | Buzău | Buzău | 115,494 | ||

| 9 | Ploiești | Prahova | 209,945 | 19 | Botoșani | Botoșani | 106,847 | ||

| 10 | Oradea | Bihor | 196,367 | 20 | Satu Mare | Satu Mare | 102,441 | ||

Education

Since the Romanian Revolution of 1989, the Romanian educational system has been in a continuous process of reform that has received mixed criticism.[268] In 2004, some 4.4 million of the population were enrolled in school. Out of these, 650,000 in kindergarten (3–6 years), 3.11 million in primary and secondary level, and 650,000 in tertiary level (universities).[269] In the same year, the adult literacy rate was 97.3% (45th worldwide), while the combined gross enrollment ratio for primary, secondary and tertiary schools was 75% (52nd worldwide).[270] Kindergarten is optional between 3 and 6 years. Since 2012, compulsory schooling starts at age 6 with the "preparatory school year" (clasa pregătitoare)[271] and is compulsory until tenth grade.[272] Primary and secondary education is divided into 12 or 13 grades. There also exists a semi-legal, informal private tutoring system used mostly during secondary school, which has prospered during the Communist regime.[273]

Higher education is aligned with the European higher education area. The results of the PISA assessment study in schools for the year 2012 placed Romania on the 45th rank out of 65 participant countries[274] and in 2016 the Romanian government released statistics showing 42% of 15-year-olds are functionally illiterate in reading.[275] though Romania often wins medals in the mathematical olympiads[276][277][278] and not only. Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași, Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca, University of Bucharest, and West University of Timișoara have been included in the QS World University Rankings' top 800.[279]

Healthcare

Romania has a universal health care system, and total health expenditures by the government are roughly 5% of the GDP.[280] It covers medical examinations, any surgical interventions, and any post-operator medical care, and provides free or subsidized medicine for a range of diseases. The state is obliged to fund public hospitals and clinics. The most common causes of death are cardiovascular diseases and cancer. Transmissible diseases, such as tuberculosis, syphilis or viral hepatitis, are quite common by European standards.[281] In 2010, Romania had 428 state and 25 private hospitals,[282] with 6.2 hospital beds per 1,000 people,[283] and over 200,000 medical staff, including over 52,000 doctors.[284] As of 2013, the emigration rate of doctors was 9%, higher than the European average of 2.5%.[285]

Culture

Arts and monuments

The topic of the origin of the Romanians began to be discussed by the end of the 18th century among the Transylvanian School scholars.[286] Several writers rose to prominence in the 19th century, including George Coșbuc, Ioan Slavici, Mihail Kogălniceanu, Vasile Alecsandri, Nicolae Bălcescu, Ion Luca Caragiale, Ion Creangă, and Mihai Eminescu, the later being considered the greatest and most influential Romanian poet, particularly for the poem Luceafărul.[287] In the 20th century, Romanian artists reached international acclaim, including Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco,[288] Mircea Eliade, Nicolae Grigorescu, Marin Preda, Liviu Rebreanu,[289] Eugène Ionesco, Emil Cioran, and Constantin Brâncuși. The latter has a sculptural ensemble in Târgu Jiu, while his sculpture Bird in Space, was auctioned in 2005 for $27.5 million.[290][291] Romanian-born Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986, while writer Herta Müller received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2009.

Prominent Romanian painters include Nicolae Grigorescu, Ștefan Luchian, Ion Andreescu Nicolae Tonitza and Theodor Aman. Notable Romanian classical composers of the 19th and 20th centuries include Ciprian Porumbescu, Anton Pann, Eduard Caudella, Mihail Jora, Dinu Lipatti and especially George Enescu. The annual George Enescu Festival is held in Bucharest in honor of the 20th century emponymous composer.[292] Contemporary musicians like Angela Gheorghiu, Gheorghe Zamfir,[293][294] Inna,[295] Alexandra Stan[296] and many others have achieved various levels of international acclaim. At the Eurovision Song Contest Romanian singers have achieved third place in 2005 and 2010.[297]

In cinema, several movies of the Romanian New Wave have achieved international acclaim. At the Cannes Film Festival, 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days by Cristian Mungiu won Palme d'Or in 2007.[298] At the Berlin International Film Festival, Child's Pose by Călin Peter Netzer won the Golden Bear in 2013.[299]

The list of World Heritage Sites includes six cultural sites located within Romania, including eight Painted churches of northern Moldavia, eight Wooden Churches of Maramureș, seven Villages with fortified churches in Transylvania, the Horezu Monastery, and the Historic Centre of Sighișoara. [300] The city of Sibiu, with its Brukenthal National Museum, was selected as the 2007 European Capital of Culture.[301] Multiple castles exist in Romania, including popular tourist attractions of Peleș Castle,[302] Corvin Castle, and "Dracula's Castle".[303]

Holidays, traditions and cuisine

There are 12 non-working public holidays, including the Great Union Day, celebrated on 1 December in commemoration of the 1918 union of Transylvania with Romania.[304] Winter holidays include the Christmas festivities and the New Year during which, various unique folklore dances and games are common: plugușorul, sorcova, ursul, and capra.[305][306] The traditional Romanian dress that otherwise has largely fallen out of use during the 20th century, is a popular ceremonial vestment worn on these festivities, especially in the rural areas.[307] Sacrifices of live pigs during Christmas and lambs during Easter has required a special derogation from EU law after 2007.[308] During Easter, painted eggs are very common, while on 1 March features mărțișor gifting, a tradition likely of Thracian origin.[309]

Romanian cuisine shares some similarities with other Balkan cuisines such as Greek, Bulgarian and Turkish cuisine.[310] Ciorbă includes a wide range of sour soups, while mititei, mămăligă (similar to polenta), and sarmale are featured commonly in main courses.[311] Pork, chicken and beef are the preferred meats, but lamb and fish are also popular.[312] [313] Certain traditional recipes are made in direct connection with the holidays: chiftele, tobă and tochitura at Christmas; drob, pască and cozonac at Easter and other Romanian holidays.[314] Țuică is a strong plum brandy reaching a 70% alcohol content which is the country's traditional alcoholic beverage, taking as much as 75% of the national crop (Romania is one of the largest plum producers in the world).[315][316] Traditional alcoholic beverages also include wine, rachiu, palincă and vișinată, but beer consumption has increased dramatically over the recent years.[317]

Sports

_(14403024996).jpg)

Association football (soccer) is the most popular sport in Romania with over 234,000 registered players as of 2010.[318] The governing body is the Romanian Football Federation, which belongs to UEFA. The Romania national football team has taken part seven times in the FIFA World Cup games and had its most successful period during the 1990s, when they reached the quarterfinals of the 1994 FIFA World Cup and was ranked third by FIFA in 1997.[319] The core player of this "Golden Generation" was Gheorghe Hagi, who was nicknamed "the Maradona of the Carpathians."[320][321] Other successful players include Nicolae Dobrin, Dudu Georgescu, Florea Dumitrache, Liță Dumitru, Ilie Balaci, Loți Bölöni, Costică Ștefănescu, Cornel Dinu or Gheorghe Popescu, and most recently Adrian Mutu, Cristian Chivu, Dan Petrescu or Cosmin Contra.

The most successful club is Steaua București, who were the first Eastern European team to win the European Champions Cup in 1986, and were runners-up in 1989. Dinamo București reached the European Champions' Cup semifinal in 1984 and the Cup Winners' Cup semifinal in 1990. Other important Romanian football clubs are Rapid București, UTA Arad, Universitatea Craiova, CFR Cluj and Petrolul Ploiești.

Tennis is the second-most-popular sport, with over 15,000 registered players.[322] Romania reached the Davis Cup finals three times (1969, 1971, 1972). The tennis player Ilie Năstase won several Grand Slam titles, and was the first player to be ranked as number 1 by ATP between 1973 and 1974. Virginia Ruzici won the French Open in 1978, and was runner-up in 1980, Simona Halep played the final in 2014 and is currently ranked 2nd by the WTA.[323]

Other popular team sports are team handball,[322] basketball[324] and rugby union. Both the men's and women's handball national teams are multiple world champions. On 13 January 2010, Cristina Neagu became the first Romanian in handball to win the IHF World Player of the Year award.[325] Basketball is widely enjoyed, especially by the youth.[324] Gheorghe Mureșan was one of the two tallest players to ever play in the NBA. In 2016, Romania was chosen as a host for the 2017 EuroBasket. The rugby national team has competed in every Rugby World Cup. Popular individual sports include athletics, chess, judo, dancesport, table tennis and combat sports (Lucian Bute, Leonard Dorin Doroftei, Mihai Leu aka Michael Loewe, Daniel Ghiță, Benjamin Adegbuyi, Andrei Stoica, etc.).[322] While it has a limited popularity nowadays, oină is a traditional Romanian sporting game similar to baseball that has been continuously practiced since at least the 14th century.[326]

Romania participated in the Olympic Games for the first time in 1900 and has taken part in 21 of the 28 summer games. It has been one of the more successful countries at the Summer Olympic Games, with a total of 306 medals won throughout the years, of which 89 gold ones, ranking 15th overall, and second (behind neighbour Hungary) of the nations that have never hosted the game. It participated at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles in defiance of a Warsaw Pact boycott and finished second in gold medals (20) and third in total medal count (53).[327] Almost a quarter of all the medals and 25 of the gold ones were won in gymnastics, with Nadia Comăneci becoming the first gymnast ever to score a perfect ten in an Olympic event at the 1976 Summer Olympics.[328] Romanian competitors have won gold medals in other Olympic sports: rowing, athletics, canoeing, wrestling, shooting, fencing, swimming, weightlifting, boxing, and judo. At the Winter Olympic Games, Romania has won only a bronze medal in bobsleigh at the 1968 Winter Olympics.

See also

- Index of Romania-related articles

- Outline of Romania

-

Romania – Wikipedia book

Romania – Wikipedia book

Notes

- ↑ "am scris aceste sfente cărți de învățături, să fie popilor rumânesti ... să înțeleagă toți oamenii cine-s rumâni creștini" "Întrebare creștinească" (1559), Bibliografia românească veche, IV, 1944, p. 6.

"... că văzum cum toate limbile au și înfluresc întru cuvintele slăvite a lui Dumnezeu numai noi românii pre limbă nu avem. Pentru aceia cu mare muncă scoasem de limba jidovească si grecească si srâbească pre limba românească 5 cărți ale lui Moisi prorocul si patru cărți și le dăruim voo frați rumâni și le-au scris în cheltuială multă ... și le-au dăruit voo fraților români, ... și le-au scris voo fraților români" Palia de la Orăștie (1581–1582), București, 1968.

În Țara Ardealului nu lăcuiesc numai unguri, ce și sași peste seamă de mulți și români peste tot locul ..., Grigore Ureche, Letopisețul Țării Moldovei, p. 133–134. - ↑ In his literary testament Ienăchiță Văcărescu writes: "Urmașilor mei Văcărești!/Las vouă moștenire:/Creșterea limbei românești/Ș-a patriei cinstire."

In the "Istoria faptelor lui Mavroghene-Vodă și a răzmeriței din timpul lui pe la 1790" a Pitar Hristache writes: "Încep după-a mea ideie/Cu vreo câteva condeie/Povestea mavroghenească/Dela Țara Românească. - ↑ In 1816, the Greek scholar Dimitrie Daniel Philippide published in Leipzig his work The History of Romania, followed by The Geography of Romania.

On the tombstone of Gheorghe Lazăr in Avrig (built in 1823) there is the inscription: "Precum Hristos pe Lazăr din morți a înviat/Așa tu România din somn ai deșteptat." - ↑ 2002 census data, based on population by ethnicity, gave a total of 535,250 Roma in Romania. Many ethnicities are not recorded, as they do not have ID cards. International sources give higher figures than the official census (e.g., UNDP's Regional Bureau for Europe, World Bank, "International Association for Official Statistics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2008.

References

- ↑ "Constitution of Romania". Cdep.ro. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ↑ "Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.148 – European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages". Council of Europe. Council of Europe. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Romanian 2011 census (final results)" (PDF) (in Romanian). INSSE. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ↑ "United Nations world population prospects".(PDF) 2015 Revision

- 1 2 "Romania". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income (source: SILC)". Eurostat Data Explorer. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ "2016 Human Development Report Romania" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2016. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ↑ "Romania Geography". aboutromania.com. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ https://qz.com/763630/one-of-the-poorest-countries-in-the-eu-could-be-its-next-tech-startup-hub/

- ↑ "Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language, 1998; New Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language, 2002" (in Romanian). Dexonline.ro. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Verres, Andréas. Acta et Epistolae. I. p. 243.

nunc se Romanos vocant

- ↑ Cl. Isopescu (1929). "Notizie intorno ai romeni nella letteratura geografica italiana del Cinquecento". Bulletin de la Section Historique. XVI: 1–90.

... si dimandano in lingua loro Romei ... se alcuno dimanda se sano parlare in la lingua valacca, dicono a questo in questo modo: Sti Rominest ? Che vol dire: Sai tu Romano, ...

- ↑ Holban, Maria (1983). Călători străini despre Țările Române (in Romanian). II. Ed. Științifică și Enciclopedică. pp. 158–161.

Anzi essi si chiamano romanesci, e vogliono molti che erano mandati quì quei che erano dannati a cavar metalli ...

- ↑ Cernovodeanu, Paul (1960). Voyage fait par moy, Pierre Lescalopier l'an 1574 de Venise a Constantinople, fol 48. Studii și materiale de istorie medievală (in Romanian). IV. p. 444.

Tout ce pays la Wallachie et Moldavie et la plus part de la Transilvanie a eté peuplé des colonies romaines du temps de Traian l'empereur ... Ceux du pays se disent vrais successeurs des Romains et nomment leur parler romanechte, c'est-à-dire romain ...

- ↑ Ion Rotaru, Literatura română veche, "The Letter of Neacșu from Câmpulung" Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine., București, 1981, pp. 62–65

- ↑ Brezeanu, Stelian (1999). Romanitatea Orientală în Evul Mediu. Bucharest: Editura All Educational. pp. 229–246.

- ↑ Goina, Călin. How the State Shaped the Nation: an Essay on the Making of the Romanian Nation in Regio – Minorities, Politics, Society.

- ↑ "Wallachia and Moldavia, 1859–61". Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- ↑ See, for example, "Rumania: Remarkable Common Ground", The New York Times (December 21, 1989).

- ↑ See the Google Ngrams for Romania, Rumania, and Roumania.

- ↑ "General principles" (in Romanian). cdep.ro. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ↑ Europe Before Rome: A Site-by-Site Tour of the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages (T. Douglas Price)

- ↑ Zilhão, João (2006). "Neanderthals and Moderns Mixed and It Matters". Evolutionary Anthropology. 15 (5): 183–195. doi:10.1002/evan.20110.

- ↑ John Noble Wilford (1 December 2009). "A Lost European Culture, Pulled From Obscurity". The New York Times (30 November 2009).

- ↑ Gibbs, Patrick. "Antiquity Vol 79 No 306 December 2005 The earliest salt production in the world: an early Neolithic exploitation in Poiana Slatinei-Lunca, Romania Olivier Weller & Gheorghe Dumitroaia". Antiquity.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 Hitchins 2014, p. 7.

- ↑ Herodotus. Histories, 4.93–4.97.

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History (Volume 10) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1996. J. J. Wilkes mentions "the Getae of the Dobrudja, who were akin to the Dacians" (p. 562)

- ↑ Mócsy, András (1974). Pannonia and Upper Moesia. Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-7714-9. See p. 364, n. 41: "If there is any justification for dividing the Thracian ethnic group, then, unlike V. Georgiev who suggests splitting it into the Thraco-Getae and the Daco-Mysi, I consider a division into the Thraco-Mysi and the Daco-Getae the more likely."

- ↑ Hitchins 2014, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Matley, Ian (1970). Romania; a Profile. Praeger. p. 85.

- ↑ Giurescu, Constantin C. (1972). The Making of the Romanian People and Language. Bucharest: Meridiane Publishing House. pp. 43, 98–101, 141.

- ↑ Eutropius, Abridgment of Roman History BOOK IX.

- ↑ Watkins, Thayer. "The Economic History of the Western Roman Empire". Retrieved 31 August 2008.

The Emperor Aurelian recognized the realities of the military situation in Dacia and, around 271 AD., withdrew Roman troops from Dacia, leaving it to the Goths. The Lower Danube once again became the northern frontier of the Roman Empire in Eastern Europe

- ↑ Jordanes (551). Getica, sive, De Origine Actibusque Gothorum. Constantinople. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Iliescu, Vl.; Paschale, Chronicon (1970). Fontes Historiae Daco-Romanae. II. București. pp. 363, 587.

- ↑ Teodor, Dan Gh. (1995). Istoria României de la începuturi până în secolul al VIII-lea. 2. București. pp. 294–325.

- ↑ Constantine VII, Porphyrogenitus (950). Constantine Porphyrogenitus De Administrando Imperio. Constantinople. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Lupșa, Cristian (1 March 2008). "Regele Decebal" (in Romanian). Lumea-Copiilor. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Împăratul Traian, strămoșul uitat" (in Romanian). Adevărul. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Mitul strămoșilor în "epopeea națională": Dacii, Columna și Burebista" (in Romanian). Realitatea TV. 13 April 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ Pop, Ioan-Aurel (Winter 2001). "The Romanians' Identity in the 16th Century According to Italian Authors" (PDF). Transylvanian Review. Romanian Cultural Foundation. 10 (4): 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2014.

- ↑ "Gesta Hungarorum, the chronicle of Bele Regis Notarius". Scribd.com. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ Makkai, László (2001). Köpeczi, Béla, ed. "History of Transylvania: III. Transylvania in the Medieval Hungarian Kingdom (896–1526)". New York: Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Columbia University Press. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Ștefănescu, Ștefan (1991). Istoria medie a României. I. Bucharest. p. 114.

- ↑ Predescu, Lucian (1940). Enciclopedia Cugetarea.

- ↑ Várkonyi, Ágnes R. (2001). "Columbia University Press". In Köpeczi, Béla. History of Transylvania: VI. The Last Decades of the Independent Principality (1660–1711). 2. New York: Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ István, Vásáry. "Cumans and Tatars". cambridge.org. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ↑ Copy of Domnitori Romani. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ Giurescu, p. 211–13. Giurescu, Constantin C. (2007) [1935]. Istoria Românilor (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura All.

- ↑ David Prodan, Supplex Libellus Valachorum, Bucharest, 1948.

- ↑ Kocsis, Karoly; Kocsis-Hodosi, Eszter (1999). Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Transylvania (1880–1992). Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Kocsis, Karoly; Kocsis-Hodosi, Eszter (2001). Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin. Simon Publications. p. 102. ISBN 1-931313-75-X.

- ↑ Gazeta de Transilvania, year XI, no. 34 of 26 April 1848, p. 140.

- ↑ Dogaru (1978), p. 862.

- ↑ Căzănișteanu (1967), p. 36.

- ↑ Năsturel (1900/1901), p. 257. Năsturel, Petre Vasiliu, Steagul, stema română, însemnele domnești, trofee (The Romanian flag [and] coat of arms; the princely insignias [and] trophies), Bucharest, 1903.

- ↑ The establishment of the Balkan national states, 1804–1920. Books.google.com. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ Bobango, Gerald J (1979). The emergence of the Romanian national State. New York: Boulder. ISBN 978-0-914710-51-6.

- ↑ "San Stefano Preliminary Treaty" (in Russian). 1878. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ The Treaty of Berlin, 1878 – Excerpts on the Balkans. Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Berlin: Fordham University. 13 July 1878. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Patterson, Michelle (August 1996). "The Road to Romanian Independence". Canadian Journal of History. Archived from the original (– Scholar search) on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Anderson, Frank Maloy; Hershey, Amos Shartle (1918). Handbook for the Diplomatic History of Europe, Asia, and Africa 1870–1914. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Horne, Charles F. "Romania's Declaration of War with Austria-Hungary". Source Records of the Great War. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Erlikman, Vadim (2004). Poteri narodonaseleniia v XX veke : spravochnik. Moscow. ISBN 5-93165-107-1.

- ↑ Bernard Anthony Cook (2001). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Taylor&Francis. p. 162. ISBN 0-8153-4057-5.

- ↑ "Text of the Treaty of Trianon". World War I Document Archive. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Malbone W. Graham (October 1944). "The Legal Status of the Bukovina and Bessarabia". The American Journal of International Law. American Society of International Law. 38 (4): 667–673. JSTOR 2192802. doi:10.2307/2192802.

- ↑ "World War I: The Players". www.mtholyoke.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ↑ "Statul National Unitar (România Mare 1919–1940)" (in Romanian). ici.ro. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ "his1". Aneir-cpce.ro. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ↑ "VIDEO Înregistrare senzațională cu Hitler: "Fără petrolul din România nu aș fi atacat niciodată URSS-ul"". adevarul.ro. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ↑ "Business in Romania: a country that's fast off the Bloc – Two years of EU membership have transformed the business face of Romania and savvy UK firms are reaping the rewards. Paul Bray reports.". The Daily Telegraph. London. 24 February 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ "Post-War Romania". www.shsu.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ↑ Ioan Scurtu; Theodora Stănescu-Stanciu; Georgiana Margareta Scurtu (2002). Istoria Românilor între anii 1918–1940 (in Romanian). University of Bucharest. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007.

- ↑ Nagy-Talavera, Nicolas M. (1970). Green Shirts and Others: a History of Fascism in Hungary and Romania. Hoover Institution Press. p. 305. ISBN 973-9432-11-5.