Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain was a gradual process, beginning effectively in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, whose general Aulus Plautius served as first governor of Roman Britain (Latin: Britannia). Great Britain had already frequently been the target of invasions, planned and actual, by forces of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire. In common with other regions on the edge of the empire, Britain had enjoyed diplomatic and trading links with the Romans in the century since Julius Caesar's expeditions in 55 and 54 BC, and Roman economic and cultural influence was a significant part of the British late pre-Roman Iron Age, especially in the south.

Between 55 BC and the 40s AD, the status quo of tribute, hostages, and client states without direct military occupation, begun by Caesar's invasions of Britain, largely remained intact. Augustus prepared invasions in 34 BC, 27 BC and 25 BC. The first and third were called off due to revolts elsewhere in the empire, the second because the Britons seemed ready to come to terms.[1] According to Augustus's Res Gestae, two British kings, Dubnovellaunus and Tincomarus, fled to Rome as suppliants during his reign,[2] and Strabo's Geography, written during this period, says that Britain paid more in customs and duties than could be raised by taxation if the island were conquered.[3]

By the 40s AD, the political situation within Britain was apparently in ferment. The Catuvellauni had displaced the Trinovantes as the most powerful kingdom in south-eastern Britain, taking over the former Trinovantian capital of Camulodunum (Colchester), and were pressing their neighbours the Atrebates, ruled by the descendants of Julius Caesar's former ally Commius.[4]

Caligula planned a campaign against the Britons in 40, but its execution was bizarre: according to Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars, he drew up his troops in battle formation facing the English Channel and, once his forces had become quite confused, ordered them to gather seashells, referring to them as "plunder from the ocean due to the Capitol and the Palace".[5]

Modern historians are unsure if that was meant to be an ironic punishment for the soldiers' mutiny or due to Caligula's derangement. Certainly this invasion attempt readied the troops and facilities that would make Claudius' invasion possible three years later. For example, Caligula built a lighthouse at Bononia (modern Boulogne-sur-Mer) that provided a model for the one built soon after at Dubris (Dover).

Claudian preparations

Three years later, in 43, possibly by re-collecting Caligula's troops, Claudius mounted an invasion force to re-instate Verica, an exiled king of the Atrebates.[6] Aulus Plautius, a distinguished senator, was given overall charge of four legions, totalling about 20,000 men, plus about the same number of auxiliaries. The legions were:

The II Augusta is known to have been commanded by the future emperor Vespasian. Three other men of appropriate rank to command legions are known from the sources to have been involved in the invasion. Cassius Dio mentions Gnaeus Hosidius Geta, who probably led the IX Hispana, and Vespasian's brother Titus Flavius Sabinus the Younger. He wrote that Sabinus was Vespasian's lieutenant, but as Sabinus was the older brother and preceded Vespasian into public life, he could hardly have been a military tribune. Eutropius mentions Gnaeus Sentius Saturninus, although as a former consul he may have been too senior, and perhaps accompanied Claudius later.[7]

Crossing and landing

The main invasion force under Aulus Plautius crossed in three divisions. The port of departure is usually taken to have been Boulogne, and the main landing at Rutupiae (Richborough, on the east coast of Kent). Neither of these locations is certain. Dio does not mention the port of departure, and although Suetonius says that the secondary force under Claudius sailed from Boulogne,[8] it does not necessarily follow that the entire invasion force did. Richborough has a large natural harbour which would have been suitable, and archaeology shows Roman military occupation at about the right time. However, Dio says the Romans sailed east to west, and a journey from Boulogne to Richborough is south to north. Some historians[9] suggest a sailing from Boulogne to the Solent, landing in the vicinity of Noviomagus (Chichester) or Southampton, in territory formerly ruled by Verica. An alternative explanation might be a sailing from the mouth of the Rhine to Richborough, which would be east to west.[10]

River battles

British resistance was led by Togodumnus and Caratacus, sons of the late king of the Catuvellauni, Cunobeline. A substantial British force met the Romans at a river crossing thought to be near Rochester on the River Medway. The battle raged for two days. Hosidius Geta was almost captured, but recovered and turned the battle so decisively that he was awarded the "Roman triumph."

The British were pushed back to the Thames. They were pursued by the Romans across the river causing some Roman losses in the marshes of Essex. Whether the Romans made use of an existing bridge for this purpose or built a temporary one is uncertain. At least one division of auxiliary Batavian troops swam across the river as a separate force.

Togodumnus died shortly after the battle on the Thames. Plautius halted and sent word for Claudius to join him for the final push. Cassius Dio presents this as Plautius needing the emperor's assistance to defeat the resurgent British, who were determined to avenge Togodumnus. However, Claudius was no military man. Claudius's arch says he received the surrender of eleven kings without any loss,[11] and Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars says that Claudius received the surrender of the Britons without battle or bloodshed.[12] It is likely that the Catuvellauni were already as good as beaten, allowing the emperor to appear as conqueror on the final march on Camulodunum. Cassius Dio relates that he brought war elephants and heavy armaments which would have overawed any remaining native resistance. Eleven tribes of South East Britain surrendered to Claudius and the Romans prepared to move further west and north. The Romans established their new capital at Camulodunum and Claudius returned to Rome to celebrate his victory. Caratacus escaped and would continue the resistance further west.

(44–60)

Vespasian took a force westwards subduing tribes and capturing oppida as he went, going at least as far as Exeter, which would appear to have become an early base for Leg. II Augusta. In 2010, two separate temporary legionary fortresses, dated at about the time of Vespasian, were partly excavated by Exeter City Archaeological Unit at St Loyes on the Roman Road between Isca and Topsham and probably reaching Bodmin.[13] Legio IX Hispana was sent north towards Lincoln (Latin: Lindum Colonia) and within four years of the invasion it is likely that an area south of a line from the Humber to the River Severn Estuary was under Roman control. That this line is followed by the Roman road of the Fosse Way has led many historians to debate the route's role as a convenient frontier during the early occupation. It is more likely that the border between Roman and Iron Age Britain was less direct and more mutable during this period however.

Late in 47 the new governor of Britain, Publius Ostorius Scapula, began a campaign against the tribes of modern-day Wales, and the Cheshire Gap. The Silures of southeast Wales caused considerable problems to Ostorius and fiercely defended the Welsh border country. Caratacus himself was defeated in the Battle of Caer Caradoc and fled to the Roman client tribe of the Brigantes who occupied the Pennines. Their queen, Cartimandua was unable or unwilling to protect him however given her own truce with the Romans and handed him over to the invaders. Ostorius died and was replaced by Aulus Didius Gallus who brought the Welsh borders under control but did not move further north or west, probably because Claudius was keen to avoid what he considered a difficult and drawn-out war for little material gain in the mountainous terrain of upland Britain. When Nero became emperor in AD 54, he seems to have decided to continue the invasion and appointed Quintus Veranius as governor, a man experienced in dealing with the troublesome hill tribes of Anatolia. Veranius and his successor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus mounted a successful campaign across Wales, famously destroying the druidical centre at Mona or Anglesey in AD 60 at what historians later called the Menai Massacre. Final occupation of Wales was postponed however when the rebellion of Boudica forced the Romans to return to the south east. The Silures were not finally conquered until circa AD 76 when Sextus Julius Frontinus' long campaign against them began to have success.

(60–78)

Following the successful suppression of Boudica's uprising, a number of new Roman governors continued the conquest by edging north. Cartimandua was forced to ask for Roman aid following a rebellion by her husband Venutius. Quintus Petillius Cerialis took his legions from Lincoln as far as York and defeated Venutius near Stanwick around 70. This resulted in the already Romanised Brigantes and Parisii tribes being further assimilated into the empire proper. Frontinus was sent into Roman Britain in 74 AD to succeed Quintus Petillius Cerialis as governor of that island. He subdued the Silures and other hostile tribes of Wales, establishing a new base at Caerleon for Legio II Augusta (Isca Augusta) and a network of smaller forts fifteen to twenty kilometres apart for his auxiliary units. During his tenure, he probably established the fort at Pumsaint in west Wales, largely to exploit the gold deposits at Dolaucothi. He retired in 78 AD, and later he was appointed water commissioner in Rome. The new governor was Gnaeus Julius Agricola, made famous through the highly laudatory biography of him written by his son-in-law, Tacitus.

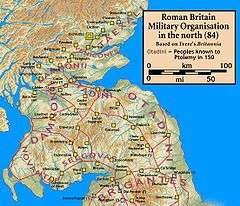

Campaigns of Agricola (78–84)

Arriving in mid-summer of 78, Agricola found several previously defeated peoples had re-established their independence. The first to be dealt with were the Ordovices of north Wales, who had destroyed a cavalry ala of Roman auxiliaries stationed in their territory. Knowing the terrain from his prior military service in Britain, he was able to move quickly to defeat and virtually exterminate them. He then invaded Anglesey, forcing the inhabitants to sue for peace.[14] The following year he moved against the Brigantes of northern England and the Selgovae along the southern coast of Scotland, using overwhelming military power to re-establish Roman control.[15]

Scotland before Agricola

Details of the early years of the Roman occupation in North Britain are unclear but began no earlier than 71, as Tacitus says that in that year Petillius Cerialis (governor 71–74) waged a successful war against the Brigantes,[16] whose territory straddled Britain along the Solway-Tyne line. Tacitus praises both Cerialis and his successor Julius Frontinus (governor 75–78), but provides no additional information on events prior to 79 regarding the lands or peoples living north of the Brigantes. The Romans certainly would have followed up their initial victory over the Brigantes in some manner. In particular, archaeology has shown that the Romans had campaigned and built military camps in the north along Gask Ridge, controlling the glens that provided access to and from the Scottish Highlands, and also throughout the Scottish Lowlands in northeastern Scotland. In describing Agricola's campaigns, Tacitus does not explicitly state that this is actually a return to lands previously occupied by Rome, where Roman occupation either had been thrown off by the Brittonic inhabitants, or had been abandoned by the Romans.

Agricola in Caledonia

Tacitus says that after a combination of force and diplomacy quieted discontent among the Britons who had been conquered previously, Agricola built forts in their territories in 79. In 80 he marched to the Firth of Tay (some historians hold that he stopped along the Firth of Forth in that year), not returning south until 81, at which time he consolidated his gains in the new lands that he had conquered, and in the rebellious lands that he had re-conquered.[17] In 82 he sailed to either Kintyre or the shores of Argyll, or to both. In 83 and 84 he moved north along Scotland's eastern and northern coasts using both land and naval forces, campaigning successfully against the inhabitants, and winning a significant victory over the northern British peoples led by Calgacus at the Battle of Mons Graupius.[18]

Prior to his recall in 84, Agricola built a network of military roads and forts to secure the Roman occupation. Existing forts were strengthened and new ones planted in northeastern Scotland along the Highland Line, consolidating control of the glens that provided access to and from the Scottish Highlands. The line of military communication and supply along southeastern Scotland and northeastern England (i.e., Dere Street) was well-fortified. In southern-most Caledonia, the lands of the Selgovae (approximating to modern Dumfriesshire and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright) were heavily planted with forts, not only establishing effective control there, but also completing a military enclosure of south-central Scotland (most of the Southern Uplands, Teviotdale, and western Tweeddale).[19] In contrast to Roman actions against the Selgovae, the territories of the Novantae, Damnonii, and Votadini were not planted with forts, and there is nothing to indicate that the Romans were at war with them.

(84–96)

Agricola was recalled to Rome by Domitian. His successors are not named in any surviving source, but it seems they were unable or unwilling to further subdue the far north. The fortress at Inchtuthil was dismantled before its completion and the other fortifications of the Gask Ridge in Perthshire, erected to consolidate the Roman presence in Scotland in the aftermath of Mons Graupius, were abandoned within the space of a few years. It is equally likely that the costs of a drawn-out war outweighed any economic or political benefit and it was more profitable to leave the Caledonians alone and only under de jure submission.

Failure to conquer Caledonia

Roman occupation was withdrawn to a line subsequently established as one of the limites (singular limes) of the empire (i.e. a defensible frontier) by the construction of Hadrian's Wall. An attempt was made to push this line north to the River Clyde-River Forth area in 142 when the Antonine Wall was constructed. This was once again abandoned after two decades and only subsequently re-occupied on an occasional basis.

The Romans retreated to the earlier and stronger Hadrian's Wall in the River Tyne-Solway Firth frontier area, this having been constructed around 122. Roman troops, however, penetrated far into the north of modern Scotland several more times. Indeed, there is a greater density of Roman marching camps in Scotland than anywhere else in Europe as a result of at least four major attempts to subdue the area.

The most notable was in 209 when the emperor Septimius Severus, claiming to be provoked by the belligerence of the Maeatae tribe, campaigned against the Caledonian Confederacy, a coalition of Brittonic Pictish[20] tribes of the north of Britain. He used the three legions of the British garrison (augmented by the recently formed 2nd Parthica legion), 9000 imperial guards with cavalry support, and numerous auxiliaries supplied from the sea by the British fleet, the Rhine fleet and two fleets transferred from the Danube for the purpose. According to Dio Cassius, he inflicted genocidal depredations on the natives and incurred the loss of 50,000 of his own men to the attrition of guerrilla tactics before having to withdraw to Hadrian's Wall. He repaired and reinforced the wall with a degree of thoroughness that led most subsequent Roman authors to attribute the construction of the wall to him. It was during the negotiations to purchase the truce necessary to secure the Roman retreat to the wall that the first recorded utterance, attributable with any reasonable degree of confidence, to a native of Scotland was made (as recorded by Dio Cassius). When Septimius Severus's wife, Julia Domna, criticised the sexual morals of the Caledonian women, the wife of a Caledonian chief, Argentocoxos, replied: "We consort openly with the best of men while you allow yourselves to be debauched in private by the worst".[21] The emperor Septimius Severus died at York while planning to renew hostilities, and these plans were abandoned by his son Caracalla.

Later excursions into Scotland by the Romans were generally limited to the scouting expeditions of exploratores in the buffer zone that developed between the walls, trading contacts, bribes to purchase truces from the natives, and eventually the spread of Christianity. The degree to which the Romans interacted with the Gaelic speaking island of Hibernia (modern Ireland) is still unresolved amongst archaeologists in Ireland. The successes and failures of the Romans in subduing the peoples of Britain are still represented in the political geography of the British Isles today.

See also

- Ancient Britain

- Roman Britain

- Roman mining

- British military history

- Itius Portus

- Roman governors of Britain

- Pugnaces Britanniae

Citations

- ↑ Dio Cassius, Roman History 49.38, 53.22, 53.25

- ↑ Augustus, Res Gestae Divi Augusti 32. The name of the second king is defaced, but Tincomarus is the most likely reconstruction.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography 4.5

- ↑ John Creighton (2000), Coins and power in Late Iron Age Britain, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Suetonius, Caligula 44–46; Dio Cassius, Roman History 59.25

- ↑ Dio Cassius, Roman History 60.19–22

- ↑ Eutropius, Abridgement of Roman History 7:13

- ↑ Suetonius, Claudius 17

- ↑ For example, John Manley, AD43: a Reassessment.

- ↑ Strabo (Geography 4:5.2) names the Rhine as a commonly used point of departure for crossings to Britain in the 1st century AD.

- ↑ Arch of Claudius

- ↑ Suetonius, Claudius 17

- ↑ Suetonius, Vespasian 4

- ↑ Tacitus & 98:363–364, Life of Agricola, Ch. 18

- ↑ Tacitus & 98:365–366, Life of Agricola, Ch. 20–21

- ↑ Tacitus & 98:362, Life of Agricola, Ch. 17

- ↑ Tacitus & 98:364–368, Life of Agricola, Ch. 19–23.

- ↑ Tacitus & 98:368–380, Life of Agricola, Ch. 24–38.

- ↑ Frere 1987:88–89, Britannia

- ↑ ^ Encyclopaedia Romana. University of Chicago. accessed March 1, 2007

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History 77.16

References

- Frere, Sheppad Sunderland (1987), Britannia: A History of Roman Britain (3rd, revised ed.), London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7102-1215-1

- Tacitus, Cornelius (98), "The Life of Cnaeus Julius Agricola", The Works of Tacitus (The Oxford Translation, Revised), II, London: Henry G. Bohn (published 1854), pp. 343–389 Check date values in:

|date=(help)

Further reading

- The Great Invasion, Leonard Cottrell, Coward–McCann, New York, 1962, hardback. Was published in the UK in 1958.

- Tacitus, Histories, Annals and De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae

- A.D. 43, John Manley, Tempus, 2002.

- Roman Britain, Peter Salway, Oxford, 1986

- Miles Russel – Ruling Britannia – History Today 8/2005 pp 5–6

- Francis Pryor. 2004. Britain BC. New York: HarperPerennial.

- Francis Pryor. 2004. Britain AD. New York: HarperCollins.

- George Shipway – Imperial Governor. 2002. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks.