Rohingya insurgency in Western Myanmar

| Rohingya insurgency in Western Myanmar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Internal conflict in Myanmar | |||||||

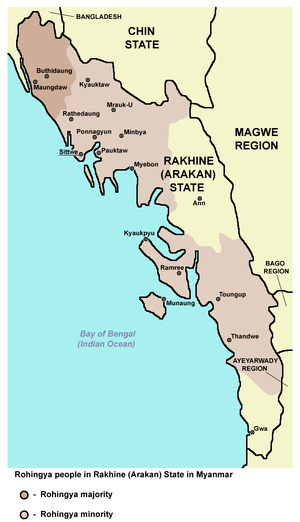

Rohingya population in Rakhine State (Arakan) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Former combatants:

|

ARSA (since 2016) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Ata Ullah[6][7] | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Rohingya National Army (1998–2001)[2][9] | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

~500 (2016)[8] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2016–17: 13 soldiers and 19 policemen killed[11][12][13][14] |

2016–17: 102 killed[11][15] and 423 arrested[16][17] | ||||||

|

2012–2017: | |||||||

|

| |||||||

The Rohingya insurgency in Western Myanmar is an ongoing insurgency in northern Rakhine State, Myanmar (formerly known as Arakan, Burma), waged by insurgents belonging to the Rohingya ethnic minority. Most clashes have occurred in the Maungdaw District, which borders Bangladesh.

From 1947 to 1961, local mujahideen fought government forces in an attempt to have the mostly Rohingya populated Mayu peninsula in northern Rakhine State secede from Myanmar, so it could be annexed by East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh).[25] During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the mujahideen lost most of its momentum and support, resulting in most of them surrendering to government forces.[26][27]

In the 1970s Rohingya Islamist movements began to emerge from remnants of the mujahideen, and the fighting culminated with the Burmese government launching a massive military operation named Operation King Dragon in 1978.[28] In the 1990s, the well-armed Rohingya Solidarity Organisation was the main perpetrator of attacks on Burmese authorities near the Myanmar-Bangladesh border.[29]

In October 2016, clashes erupted on the Myanmar-Bangladesh border, resulting in the deaths of at least 40 people, excluding civilians.[30][31][32] In November 2016, violence erupted again, bringing the death toll to 134.[11]

Background

The Rohingya people are an ethnic minority that mainly live in the northern region of Rakhine State, Myanmar, and have been described as one of the world's most persecuted minorities.[33][34][35] They describe themselves as descendants of Arab traders who settled in the region many generations ago.[33] Some scholars have stated that they have been present in the region since the 15th century.[36] However, they have been denied citizenship by the government of Myanmar, which sees them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.[33] In modern times, the persecution of Rohingyas in Myanmar dates back to the 1970s.[37] Since then, Rohingya people have regularly been made the target of persecution by the government and nationalist Buddhists.[38]

Mujahideen separatist movements (1947–1960s)

Early separatist insurgency

In May 1946, Muslim leaders from Arakan, Burma (present-day Rakhine State, Myanmar) met with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, and asked for the formal annexation of two townships in the Mayu region, Buthidaung and Maungdaw, by East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh). Two months later, the North Arakan Muslim League was founded in Akyab (present-day Sittwe, capital of Rakhine State), which also asked Jinnah to annex the region.[39] Jinnah refused, saying that he could not interfere with Burma's internal matters. After Jinnah's refusal, proposals were made by Muslims in Arakan to the newly formed post-independence government of Burma, asking for the concession of the two townships to Pakistan. The proposals were rejected by the Burmese parliament.[40]

Local mujahideen were subsequently formed against the Burmese government,[41] and began targeting government soldiers stationed in the area. Led by Mir Kassem, the newly formed mujahideen movement began gaining territory, driving out local Rakhine communities from their villages, some of whom fled to East Pakistan.[42]

In November 1948, martial law was declared in the region, and the 5th Battalion of the Burma Rifles and the 2nd Chin Battalion were sent to liberate the area. By June 1949, the Burmese government's control over the region was reduced to the city of Akyab, whilst the mujahideen had possession of nearly all of northern Arakan. After several months of fighting, Burmese forces were able to push the mujahideen back into the jungles of the Mayu region, near the country's border with East Pakistan.

In 1950, the Pakistani government warned its counterparts in Burma about their treatment of Muslims in Arakan. Burmese Prime Minister U Nu immediately sent a Muslim diplomat, Pe Khin, to negotiate a memorandum of understanding, so that Pakistan would cease sending aid to the mujahideen. In 1954, Kassem was arrested by Pakistani authorities, and many of his followers surrendered to the government.[3]

The post-independence government accused the mujahideen of encouraging the illegal immigration of thousands of Bengalis from East Pakistan into Arakan during their rule of the area, a claim that has been highly disputed over the decades, as it brings into question the legitimacy of the Rohingya as an ethnic group of Myanmar.[26]

Military operations against the mujahideen

Between 1950 and 1954, the Burma Army launched several military operations against the remaining mujahideen in northern Arakan.[43] The first military operation was launched in March 1950, followed by a second named Operation Mayu in October 1952. Several mujahideen leaders agreed to disarm and surrender to government forces following the successful operations.[39]

In the latter half of 1954, the mujahideen again began to carry out attacks on local authorities and military units stationed around Maungdaw, Buthidaung and Rathedaung. In protest, hundreds of Rakhine Buddhist monks began hunger strikes in Rangoon (present-day Yangon),[26] and in response the government launched Operation Monsoon in October 1954.[39] The Tatmadaw managed to capture the main strongholds of the mujahideen and managed to kill several of their leaders. The operation successfully reduced the mujahideen's influence and support in the region.[10]

Decline and fall of the mujahideen

.jpg)

In 1957, 150 mujahideen, led by Shore Maluk and Zurah, surrendered to government forces. On 7 November 1957, 214 additional mujahideen under the leadership of al-Rashid disarmed and surrendered to government forces.[27]

In the beginning of the 1960s, the mujahideen began to lose its momentum after the governments of Myanmar (Burma) and Pakistan (which controlled Bangladesh at the time) began negotiating on how to deal with the insurgents at their border. On 4 July 1961, 290 mujahideen in southern Maungdaw Township surrendered their arms in front of Brigadier-General Aung Gyi, the then Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Burmese Army.[44] On 15 November 1961, the few remaining mujahideen surrendered to Aung Gyi in the eastern region of Buthidaung.[26]

A few dozen insurgents remained under the command of Zaffar Kawal, another group of 40 insurgents were led by Abdul Latif, and a mujahideen faction of 80 insurgents were led by Annul Jauli. All these groups lacked local support and a unifying ideology, which lead them to become rice smugglers around the end of the 1960s.[27]

Rohingya Islamist movements (1972–present)

Islamist movements in the 1970s and 1980s

On 15 July 1972, former mujahideen leader Zaffar Kawal founded the Rohingya Liberation Party (RLP), after mobilising various former mujahideen factions under his command. Zaffar appointed himself Chairman of the party, Abdul Latif as Vice Chairman and Minister of Military Affairs, and Muhammad Jafar Habib as the Secretary General, a graduate from Rangoon University. Their strength increased from 200 fighters in the beginning to 500 by 1974. The RLP was largely based in the jungles of Buthidaung, and were armed with weapons smuggled from Bangladesh. After a massive military operation by the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) in July 1974, Zaffar and most of his men fled across the border into Bangladesh.[27][45]

In 1974, Muhammad Jafar Habib, the former Secretary of the RLP, founded the Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF), after the failure and dissolution of the RLP. The RPF had around 70 fighters,[27][2] Habib as self-appointed Chairman, Nurul Islam, a Yangon-educated lawyer, as Vice-Chairman, and Muhammad Yunus, a medical doctor, as Secretary General.[27]

In March 1978, government forces launched a massive military operation named Operation King Dragon in northern Arakan (Rakhine State), with the focus of expelling Rohingya insurgents in the area.[28] As the operation extended farther northwest, hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas crossed the border seeking refuge in Bangladesh.[2][46][47]

In 1982, more radical elements broke away from the Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF), and formed the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO).[1][2] It was led by Muhammad Yunus, the former Secretary General of the RPF. The RSO became the most influential and extreme faction amongst Rohingya insurgent groups; by basing itself on religious grounds it gained support from various Islamist groups, such as Jamaat-e-Islami in Bangladesh and Pakistan, Hizb-e-Islami in Afghanistan, Hizb-ul-Mujahideen (HM) in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, and Angkatan Belia Islam sa-Malaysia (ABIM) and the Islamic Youth Organisation of Malaysia in Malaysia.[2][47]

On 15 October 1982, the Burmese Citizenship Law was introduced, and with the exception of the Kaman people, most Muslims in the country were denied an ethnic minority classification, and thus were denied Burmese citizenship.[48]

A more moderate Rohingya insurgent group, the Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front (ARIF), was founded in 1986 by Nurul Islam, the former Vice-Chairman of the Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF), after uniting remnants of the old RPF and a handful of defectors from the RSO.[2]

Military expansions in the 1990s

In the early 1990s, the military camps of the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO) were located in the Cox's Bazar District in southern Bangladesh. RSO possessed a significant arsenal of light machine-guns, AK-47 assault rifles, RPG-2 rocket launchers, claymore mines and explosives, according to a field report conducted by correspondent Bertil Lintner in 1991.[29] The Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front (ARIF) was mostly armed with British manufactured 9mm Sterling L2A3 sub-machine guns, M-16 assault rifles and .303 rifles.[29]

The military expansion of the RSO resulted in the government of Myanmar launching a massive counter-offensive to expel RSO insurgents along the Bangladesh-Myanmar border. In December 1991, Tatmadaw soldiers crossed the border and accidentally attacked a Bangladeshi military outpost, causing a strain in Bangladeshi-Myanmar relations. By April 1992, more than 250,000 Rohingya civilians had been forced out of northern Rakhine State (Arakan) as a result of the increased military operations in the area.[2]

In April 1994, around 120 RSO insurgents entered Maungdaw Township in Myanmar by crossing the Naf River which marks the border between Bangladesh and Myanmar. On 28 April 1994, nine out of twelve bombs planted in different areas in Maungdaw by RSO insurgents exploded, damaging a fire engine and a few buildings, and seriously wounding four civilians.[49]

On 28 October 1998, the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation merged with the Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front and formed the Arakan Rohingya National Organisation (ARNO), operating in-exile in Cox's Bazaar.[2] The Rohingya National Army (RNA) was established as its armed wing.

One of the several dozen videotapes obtained by CNN from Al-Qaeda's archives in Afghanistan in August 2002 allegedly showed fighters from Myanmar training in Afghanistan.[50] Other videotapes were marked with "Myanmar" in Arabic, and it was assumed that the footage was shot in Myanmar, though this has not been validated.[2][47] According to intelligence sources in Asia, Rohingya recruits in the RSO were paid a 30,000 Bangladeshi taka ($525 USD) enlistment reward, and a salary of 10,000 taka ($175) per month. Families of fighters who were killed in action were offered 100,000 taka ($1,750) in compensation, a promise which lured many young Rohingya men, who were mostly very poor, to travel to Pakistan, where they would train and then perform suicide attacks in Afghanistan.[2][47]

The Islamic extremist organisations Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami[51] and Harkat-ul-Ansar[52] also claimed to have branches in Myanmar.

2016–17 border clashes

On 9 October 2016, hundreds of unidentified insurgents attacked three Burmese border posts along Myanmar's border with Bangladesh. According to government officials in the mainly Rohingya border town of Maungdaw, the attackers brandished knives, machetes and homemade slingshots that fired metal bolts. Several dozen firearms and boxes of ammunition were looted by the attackers from the border posts. The attack resulted in the deaths of nine border officers.[31] On 11 October 2016, four Tatmadaw soldiers were killed on the third day of fighting.[32] Following the attacks, reports emerged of several human rights violations allegedly perpetrated by Burmese security forces in their crackdown on suspected Rohingya insurgents.[53]

Government officials in Rakhine State originally blamed the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO), an Islamist insurgent group mainly active in the 1980s and 1990s, for the attacks;[54] however, on 17 October 2016, a group calling itself Harakah al-Yaqin (Faith Movement) released a video on several social media sites claiming responsibility.[55] In the following days, six other groups released statements, all citing the same leader.[56]

On 15 November 2016, the Tatmadaw announced that 69 Rohingya insurgents and 17 security forces (10 policemen, 7 soldiers) had been killed in recent clashes in northern Rakhine State, bringing the death toll to 134 (102 insurgents and 32 security forces). It was also announced that 234 people suspected of being connected to the attack were arrested.[11]

On 30 December 2016, nearly two dozen prominent human rights activists, including Malala Yousafzai, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Richard Branson, called on the United Nations Security Council to intervene and end the "ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity" being perpetrated in northern Rakhine State.[57]

In March 2017, a police document obtained by Reuters listed 423 Rohingyas detained by the police since 9 October 2016, 13 of whom were children, the youngest being ten years old. Two police captains in Maungdaw verified the document and justified the arrests, with one of them saying, "We the police have to arrest those who collaborated with the attackers, children or not, but the court will decide if they are guilty; we are not the ones who decide." Myanmar police also claimed that the children had confessed to their alleged crimes during interrogations, and that they were not beaten or pressured during questioning. The average age of those detained is 34, the youngest is 10, and the oldest is 75.[16][17]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Rohingya Solidarity Organization | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Bangladesh Extremist Islamist Consolidation". by Bertil Lintner. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- 1 2 U Nu, U Nu: Saturday's Son, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press) 1975, p. 272.

- 1 2 Defence Services Historical Museum and Research Institute

- ↑ "Myanmar arms non-Muslim civilians in Rakhine". www.aljazeera.com. 3 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ↑ Millar, Paul (16 February 2017). "Sizing up the shadowy leader of the Rakhine State insurgency". Southeast Asia Globe Magazine. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ↑ J, Jacob (15 December 2016). "Rohingya militants in Rakhine have Saudi, Pakistan links, think tank says".

- 1 2 CNN, Katie Hunt. "Myanmar Air Force helicopters fire on armed villagers in Rakhine state". CNN. Cable News Network. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ "PRESS RELEASE: Rohingya National Army (RNA) successfully raided a Burma Army Camp 30 miles from nort...". www.rohingya.org. 28 May 2001. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Yegar, Moshe (2002). "Between integration and secession: The Muslim communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma/Myanmar". Lanham. Lexington Books. p. 37,38,44. ISBN 0739103563. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Slodkowski, Antoni (15 November 2016). "Myanmar army says 86 killed in fighting in northwest". Reuters India. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Eight dead in clashes between Myanmar army and militants in Rakhine". The Guardian. 13 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ "Eight dead in clashes between Myanmar army and militants in Rakhine". Reuters. 13 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ "8 killed in surge of Rakhine violence: Tatmadaw". Frontier Myanmar. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ "Myanmar: 28 killed in new violence in Rakhine state". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- 1 2 Lone, Wa; Lewis, Simon; Das, Krishna N. (17 March 2017). "Exclusive: Children among hundreds of Rohingya detained in Myanmar crackdown". Reuters. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Hundreds of Rohingya held for consorting with insurgents in Bangladesh - Regional | The Star Online". www.thestar.com.my. 18 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rohingyas and the Right to have Rights". Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ↑ Tan, Vivian (3 May 2017). "Over 168,000 Rohingya likely fled Myanmar since 2012 - UNHCR report". UNHCR. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ↑ "Press Release" (PDF). Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 21 August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ↑ "Burma violence: 20,000 displaced in Rakhine state". BBC News. 28 October 2012. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ "Burma jails 25 Buddhists for mob killings of 36 Muslims in Meikhtila". The Guardian. 11 July 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ↑ Hodal, Kate (22 March 2013). "Ethnic violence erupts in Burma leaving scores dead". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Burmese government 'kills more than 1,000 Rohingya Muslims' in crackdown". The Independent. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ Yegar, Moshe (1972). Muslims of Burma. Wiesbaden: Verlag Otto Harrassowitz. p. 96.

- 1 2 3 4 Yegar, Moshe (1972). Muslims of Burma. pp. 98–101.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pho Kan Kaung (May 1992). The Danger of Rohingya. Myet Khin Thit Magazine No. 25. pp. 87–103.

- 1 2 Escobar, Pepe (October 2001). "Asia Times: Jihad: The ultimate thermonuclear bomb". Asia Times.

- 1 2 3 Lintner, Bertil (19 October 1991). Tension Mounts in Arakan State. This news-story was based on interview with Rohingyas and others in the Cox’s Bazaar area and at the Rohingya military camps in 1991: Jane’s Defence Weekly.

- ↑ "Myanmar Army Evacuates Villagers, Teachers From Hostilities in Maungdaw". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Myanmar policemen killed in Rakhine border attack". BBC News. 9 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Rakhine unrest leaves four Myanmar soldiers dead". BBC News. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 Kevin Ponniah (5 December 2016). "Who will help Myanmar's Rohingya?". BBC News.

- ↑ Matt Broomfield (10 December 2016). "UN calls on Burma's Aung San Suu Kyi to halt 'ethnic cleansing' of Rohingya Muslims". The Independent. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ↑ "New wave of destruction sees 1,250 houses destroyed in Myanmar's Rohingya villages". International Business Times. 21 November 2016.

- ↑ Leider, Jacques (2013). Rohingya: the name, the movement and the quest for identity. Myanmar Egress and the Myanmar Peace Center. pp. 204–255.

- ↑ "Rohingya Refugees Seek to Return Home to Myanmar". Voice of America. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "Myanmar seeking ethnic cleansing, says UN official as Rohingya flee persecution". The Guardian. 24 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Thit Maung, Yebaw (1989). Civil Insurgency in Burma. Yangon: Ministry of Information. p. 30.

- ↑ Hugh Tinker, The Union of Burma: A Study of the First Year of Independence, (London, New York, and Toronto: Oxford University Press) 1957, p. 357.

- ↑ Aye Chan (2–3 June 2011). On the Mujahid Rebellion in Arakan read in the International Conference of Southeast Asian Studies at Pusan University of Foreign Studies, Republic of Korea.

- ↑ Thit Maung, Yebaw (1989). Civil Insurgency in Burma. Yangon: Ministry of Information. p. 28.

- ↑ Yegar, Moshe (2002). "Between integration and secession: The Muslim communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma/Myanmar". Lanham. Lexington Books. pp. 44–45. ISBN 0739103563. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ Khit Yay Tatmaw Journal. Yangon: Burmese Army. 18 July 1961. p. 5.

- ↑ "Rohingya the easy prey". The Daily Star. 9 May 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ Lintner, Bertil (1999). Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency Since 1948,. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. pp. 317–8.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bangladesh: Breeding ground for Muslim terror". by Bertil Lintner. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ "Burmese Citizenship Law". Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ↑ "Rohingya Terrorists Plant Bombs, Burn Houses in Maungdaw". Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ↑ "Rohingyas trained in different Al-Qaeda and Taliban camps in Afghanistan". By William Gomes. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ↑ Rohan Gunaratna; Khuram Iqbal (1 January 2012). Pakistan: Terrorism Ground Zero. Reaktion Books. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-1-78023-009-2.

- ↑ Ved Prakash. Terrorism in Northern India: Jammu and Kashmir and the Punjab. Gyan Publishing House. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-81-7835-703-4.

- ↑ James Griffiths (25 November 2016). "Is The Lady listening? Aung San Suu Kyi accused of ignoring Myanmar's Muslims". CNN. Cable News Network.

- ↑ "Myanmar: Fears of violence after deadly border attack". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ "Islamist fears rise in Rohingya-linked violence". Bangkok Post. Post Publishing PCL. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ↑ McPherson, Poppy (17 November 2016). "‘It will blow up’: fears Myanmar's deadly crackdown on Muslims will spiral out of control". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ↑ Watson, Angus (30 December 2016). "Nobel winners condemn Myanmar violence in open letter". CNN. Cable News Network. Retrieved 31 December 2016.