Rockefeller Center

|

Rockefeller Center | |

|

View from the northeast of 30 Rockefeller Plaza at the heart of the complex | |

| |

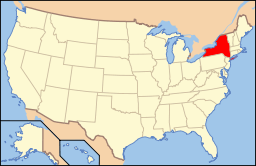

| Location | Midtown Manhattan, New York City, NY |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′31″N 73°58′45″W / 40.75861°N 73.97917°WCoordinates: 40°45′31″N 73°58′45″W / 40.75861°N 73.97917°W |

| Area | 22 acres (8.8 ha) |

| Built | 1930–1939 |

| Architect | Raymond Hood |

| Architectural style | Modern, Art Deco |

| NRHP Reference # | 87002591 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 23, 1987[1] |

| Designated NHL | December 23, 1987[2] |

Rockefeller Center is a large complex consisting of 19 high-rise commercial buildings covering 22 acres (89,000 m2) between 48th and 51st Streets in New York City. Commissioned by the Rockefeller family, it is located in the center of Midtown Manhattan, spanning the area between Fifth Avenue and Sixth Avenue. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1987.[2][3][4]

It is famous for its annual Christmas tree lighting.[5]

History

Rockefeller Center was named after John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who leased the space from Columbia University in 1928 and developed it beginning in 1930. Rockefeller initially planned a syndicate to build an opera house for the Metropolitan Opera on the site, but changed plans after the stock market crash of 1929 and the Metropolitan's continual delays to hold out for a more favorable lease, causing Rockefeller to move forward without them. Rockefeller stated, "It was clear that there were only two courses open to me. One was to abandon the entire development. The other to go forward with it in the definite knowledge that I myself would have to build it and finance it alone."[6] He took on the enormous project as the sole financier, on a 27-year lease[7] (with the option for three 21-year renewals for a total of 87 years) for the site from Columbia; negotiating a line of credit with the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and covering ongoing expenses through the sale of oil company stock. The initial cost of acquiring the space, razing some of the existing buildings and constructing new buildings was estimated at $250 million.[8]

It was the largest private building project ever undertaken in modern times.[9] Construction of the 14 buildings in the Art Deco style (without the original opera house proposal) began on May 17, 1930, and the buildings were completed and opened in 1939. Principal builder and "managing agent" for the massive project was John R. Todd. Principal architect was Raymond Hood, working with and leading three architectural firms on a team that included a young Wallace Harrison, later to become the family's principal architect and adviser to Nelson Rockefeller. The construction of the project employed over 40,000 people.[10]

It was the public relations pioneer Ivy Lee, the prominent adviser to the family, who first suggested the name "Rockefeller Center" for the complex, in 1931. Rockefeller, Jr., initially did not want the Rockefeller family name associated with the commercial project, but was persuaded on the grounds that the name would attract far more tenants.[11]

What could have become a major controversy in the mid-1930s concerned the last of the four European buildings that remained unnamed. Ivy Lee and others made attempts to rent the space to German commercial concerns and name it the Deutsches Haus. Rockefeller ruled this out after being advised of Hitler's Nazi march toward World War II, and thus the empty office site became the International Building North.[12]

This subsequently became the primary location of the U.S. operations of British Intelligence, British Security Coordination (BSC) during the War, with Room 3603 becoming the principal operations center for Allied intelligence, organized by William Stephenson, as well as the office of the future head of what was later to become the Central Intelligence Agency, Allen Dulles.[13][14]

In 1985, Columbia University sold the land beneath Rockefeller Center to the Rockefeller Group for $400 million.[15] In 1989, Mitsubishi Estate, a real estate company of the Mitsubishi Group, purchased the entire Rockefeller Center complex, and its owner, Rockefeller Group. In 1996, the entire complex was purchased by a consortium of owners that included Goldman Sachs (which had 50 percent ownership), Gianni Agnelli, Stavros Niarchos, and David Rockefeller, who organized the consortium. Tishman Speyer, led by Jerry Speyer, a close friend of David Rockefeller, and the Lester Crown family of Chicago, bought the original 14 buildings and land in 2000 for $1.85 billion.[16]

Buildings in the complex

The current Center is a combination of two building complexes: the original 14 Art Deco office buildings from the 1930s, one building across 51st Street built in 1947, and a set of four International-style towers built along the west side of Avenue of the Americas during the 1960s and 1970s.

Original complex

The landmark buildings comprise over 8,000,000 square feet (743,000 m2) on 22 acres (89,000 m2) in Midtown, bounded by Fifth and Sixth avenues, and from 48th Street to 51st Street. These are co-owned by Tishman-Speyer, and open to the public.

- 1 Rockefeller Plaza – The original Time–Life Building; an original tenant was General Dynamics, for whom the building was briefly named.

- 10 Rockefeller Plaza – Originally the Holland House, then the Eastern Air Lines Building. Currently home of Today Show studios[17] and the Nintendo New York store.

- 30 Rockefeller Plaza ("30 Rock") – Originally the RCA Building, in 1988 it was renamed the GE Building, and in 2015 became the Comcast Building. Headquarters of NBC, the Rainbow Room restaurant is located on the 65th floor.

- 50 Rockefeller Plaza – Formerly the Associated Press Building and home to many news agencies. Isamu Noguchi's large, nine-ton stainless steel panel, News, holds the place of honor above the building's entrance. Noguchi's design depicts the various forms of communications used by journalists in the 1930s. The only building in the Center built to the outer limits of its lot line, 50 Rock took its shape from the main tenant's need for a single, undivided, loft-like newsroom as large as the lot could accommodate. At one point, four million feet of transmission wire were embedded in conduits on the building's fourth floor.

- 1230 Avenue of the Americas – Formerly U.S. Rubber/Uniroyal Building, now the Simon & Schuster Building

- 1250 Avenue of the Americas – Serves as an annex building to 30 Rock.

- 1260 Avenue of the Americas – Radio City Music Hall

- 1270 Avenue of the Americas – Originally the RKO Pictures Building, later the American Metal Climax (AMAX) Building

- 600 Fifth Avenue – Formerly the Sinclair Oil Building

- 610 Fifth Avenue – La Maison Francaise

- 620 Fifth Avenue – The British Empire Building

- 626 Fifth Avenue – Palazzo d'Italia

- 45 Rockefeller Plaza – The International Building, also bears the address 630 Fifth Ave.

- 636 Fifth Avenue – The International Building North

- 1236 Avenue of the Americas – The Center Theatre; the only structure in the original Rockefeller Center to be demolished (1954); used as an NBC television studio at the time of demolition, it was replaced by an extension of 1230 Avenue of the Americas.

Extensions

- 75 Rockefeller Plaza – built in 1947, originally the Esso Building, later the Time Warner Building; now owned by Mohamed Al Fayed[18] and managed by RXR Realty[19]

- 1211 Avenue of the Americas – Originally the Celanese Building, now the News Corp Building; 1211 is owned by an affiliate of Beacon Capital Partners, and leasing is managed by Cushman & Wakefield.[20]

- 1221 Avenue of the Americas – formerly the McGraw-Hill Building; owned by the Rockefeller Group

- 1251 Avenue of the Americas – formerly the Exxon Building[21]

- 1271 Avenue of the Americas –formerly the Time & Life Building; owned by the Rockefeller Group

30 Rockefeller Plaza

.jpg)

The centerpiece of Rockefeller Center is the 70-floor, 872 ft (266 m)-tall building at 30 Rockefeller Center, centered behind the sunken plaza. It is alternatively known as the Comcast Building and 30 Rock (also the name of a comedy television show), and formerly known as the RCA Building and then the GE Building. The building is the setting for the famous Lunchtime atop a Skyscraper photograph, taken by Charles C. Ebbets in 1932 of construction workers sitting on a steel beam without safety harnesses eating lunch above an 840-foot (260 m) drop to the ground.

The RCA Building was renamed in 1988, two years after General Electric (GE) re-acquired RCA, which it helped found in 1919, and then it was renamed the Comcast Building in 2015 after Comcast purchased General Electric's entertainment assets in 2013. The famous Rainbow Room restaurant is located on the 65th floor; the Rockefeller family office occupies the 54th through 56th floors. The skyscraper is the headquarters of NBC and houses most of the network's New York TV studios, including 6A, former home of Late Night with David Letterman, Late Night with Conan O'Brien, and The Dr. Oz Show; 6B, home of Late Night with Jimmy Fallon and now home of The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon; 8G, home of Late Night with Seth Meyers; 8H, former radio home of the NBC Symphony (conducted by Arturo Toscanini), and since 1975 home of Saturday Night Live; plus the operations of NBC News, MSNBC and network flagship station WNBC-TV. NBC currently owns the space it occupies in the building as a condominium arrangement. Rockefeller Center's legacy as "Radio City" has its roots at 30 Rock. Until 1988, the building also housed the studio and operations of the company's flagship radio station WNBC, which ceased broadcasting that year when its frequency was sold by NBC.[22]

Unlike most other Art Deco towers built during the 1930s, the Comcast Building was constructed as a slab with a flat roof and since 1933 has been home of the Center's observation deck, the Top of the Rock. The Center's owner, Tishman Speyer Properties, carried out a $75 million makeover of the observation area between 1985 and 2005. It spans from the 67th–70th floors and includes a multimedia exhibition exploring the history of the Center. On the 70th floor, accessible by both stairs and elevator, there is a 20-foot (6.1 m) wide viewing area, allowing visitors a unique 360-degree panoramic view of New York City.[23][24]

At the front of 30 Rock is the Lower Plaza, in the very center of the complex, which is reached from 5th Avenue through the Channel Gardens and Promenade. The acclaimed sculptor Paul Manship was commissioned in 1933 to create a masterwork (see below) to adorn the central axis, below the famed annual Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree, but all the other original plans to fill the space were abandoned over time.

In 1936, The Rink at Rockefeller Center was constructed after Nelson Rockefeller found that a new system had been invented allowing artificial outdoor ice skating, enabling him to bring the pastime to midtown New York City.[25] An immediate tourist attraction, the rink has become one of the most famous skating rinks in the world.[26]

Radio City Music Hall

Radio City Music Hall, at 50th Street and Sixth Avenue, was completed in December 1932. At the time, it was promoted as the largest and most opulent theater in the world. Its original intended name was the "International Music Hall"[27] but this was changed to reflect the name of its neighbor, "Radio City," as the new NBC Studios in the RCA Building were known. RCA was one of the complex's first and most important tenants and the entire Center itself was sometimes referred to as "Radio City."

The Music Hall was planned by a consortium of three architectural firms, who employed Edward Durell Stone to design the exterior. Through the direction of Abby Rockefeller, the interior design was given to Donald Deskey, an exponent of the European Modernist style and innovator of a new American design aesthetic. Deskey believed the space would be best served by sculptures and wall paintings and commissioned various artists for the large elaborate works in the theater. The Music Hall seats 6,000 people and after an initial slow start became the single biggest tourist destination in the city. Its interior was declared a New York City landmark in 1978. Painstakingly restored in 1999, the Music Hall interiors are one of the world's greatest examples of Art Deco design.

In 1979, after decades as a premiere showcase for motion pictures and elaborate stage shows, the theater converted to presenting touring performers and special events. Each holiday season features the annual musical stage show, the Radio City Christmas Spectacular, a tradition for more than 70 years. The enormous stage, with its elevators and turntables, has also offered Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, the Grammy and Tony Awards, and countless other events. One of New York's most popular tourist attractions, the Music Hall has been attended by more than 300 million people.

Underground concourse

A series of shop- and restaurant-filled, underground pedestrian passages stretch from 47th Street to 51st Street, and from Fifth Avenue to Seventh Avenue. Access is via lobby stairways in the six landmark buildings, through restaurants surrounding the Concourse-level skating rink, and elevators to the north and south of the rink. There is a connection to the New York City Subway via the western concourse, to 47th–50th Streets – Rockefeller Center station below Sixth Avenue (B D F M trains).

Pre-existing buildings

Two small buildings abut the north and south corners of 1250 Avenue of the Americas. These buildings exist as a result of two tenants, one a leaseholder, the other the property owner, who refused to sell their rights to Rockefeller during construction. In 1892, a trio of Irishmen leased the property at 1240 Sixth Avenue, and opened Hurley's, a popular pub that operated through prohibition as a speakeasy. Rockefeller bought the building, but their lease trumped his property rights. They offered to sell their rights to him for $250 million (roughly the cost of the entire complex), which he refused. Meanwhile, at 1258 Sixth Avenue on the other corner, owner John F. Maxwell simply refused to sell. In the end, Rockefeller was forced to construct the center around the existing buildings.[28]

Sculptures, artwork, and features

Flags

Some 200 flagpoles line the plaza at street level. Flagpoles around the plaza display flags of United Nations member countries, the U.S. states and territories, or decorative and seasonal motifs. During national and state holidays, every pole carries the flag of the United States.[29]

Center art

Rockefeller Center represents a turning point in the history of architectural sculpture: it is among the last major building projects in the United States to incorporate a program of integrated public art. Sculptor Lee Lawrie contributed the largest number of individual pieces – twelve, including the statue of Atlas facing Fifth Avenue and the conspicuous friezes above the main entrance to the Comcast Building. Artist Léon-Victor Solon designed the color scheme for Rockefeller Center and served as the colorist for Lee Lawrie's pieces.[30]

A large number of artists contributed work at the Center, including Isamu Noguchi, whose gleaming stainless steel bas-relief, News, over the main entrance to 50 Rockefeller Plaza (the Associated Press Building) was a standout. At the time it was the largest metal bas-relief in the world. Other artists included Carl Milles, Hildreth Meiere, Margaret Bourke-White, Dean Cornwell, and Leo Friedlander.

Prometheus

Paul Manship's highly recognizable bronze gilded statue of the Greek legend of the Titan Prometheus recumbent, bringing fire to mankind, features prominently in the sunken plaza at the front of the Comcast Building. The model for Prometheus was Leonardo (Leon) Nole, and the inscription, a paraphrase from Aeschylus, on the granite wall behind, reads: "Prometheus, teacher in every art, brought the fire that hath proved to mortals a means to mighty ends."

Man at the Crossroads

In 1932, the Mexican socialist artist Diego Rivera (whose sponsor was the Museum of Modern Art and whose patron at the time was Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, the wife of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.), was commissioned by their son Nelson Rockefeller to create a color fresco for the 1,071-square-foot (99 m2) wall in the lobby of the then-RCA Building. This was after Nelson had been unable to secure the commissioning of either Matisse or Picasso. Previously Rivera had painted a controversial fresco in Detroit titled Detroit Industry, commissioned by Abby and John's friend, Edsel Ford, who later became a MoMA trustee.

Thus it came as no real surprise when his Man at the Crossroads became controversial, as it contained Moscow May Day scenes and a clear portrait of Lenin, not apparent in initial sketches. After Nelson issued a written warning to Rivera to replace the offending figure with an anonymous face, Rivera refused (after offering to counterbalance Lenin with a portrait of Lincoln), and so he was paid for his commission and the mural papered over at the instigation of Nelson, who was to become the Center's flamboyant president.

Nine months later, after all attempts to save the fresco were explored – including relocating it to Abby's Museum of Modern Art – it was destroyed as a last option.[31][32] (Rivera re-created the work later in Mexico City in modified form, from photographs taken by an assistant, Lucienne Bloch.)

Rivera's fresco in the Center was replaced with a larger mural by the Catalan artist Josep Maria Sert, titled American Progress, depicting a vast allegorical scene of men constructing modern America. Containing figures of Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, it wraps around the west wall of the Grand Lobby of the Comcast Building.[33]

Rockefeller plaque

In 1962, the center management placed a plaque at the plaza with a list of principles in which John D. Rockefeller, Jr. believed, and first expressed in 1941. It reads:[34]

I believe in the supreme worth of the individual and in his right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

I believe that every right implies a responsibility; every opportunity, an obligation; every possession, a duty.

I believe that the law was made for man and not man for the law; that government is the servant of the people and not their master.

I believe in the Dignity of labor, whether with head or hand; that the world owes no man a living but that it owes every man an opportunity to make a living.

I believe that thrift is essential to well ordered living and that economy is a prime requisite of a sound financial structure, whether in government, business or personal affairs.

I believe that truth and justice are fundamental to an enduring social order.

I believe in the sacredness of a promise, that a man's word should be as good as his bond; that character not wealth or power or position – is of supreme worth.

I believe that the rendering of useful service is the common duty of mankind and that only in the purifying fire of sacrifice is the dross of selfishness consumed and the greatness of the human soul set free.

I believe in an all-wise and all-loving God, named by whatever name, and that the individuals highest fulfilment, greatest happiness, and widest usefulness are to be found in living in harmony with His Will.

I believe that love is the greatest thing in the world; that it alone can overcome hate; that right can and will triumph over might.

Lego set

In November 2010, former architect and Lego fan Adam Reed Tucker designed a Lego replica of the center for the Lego Architecture series.

Gallery

30 Rockefeller Plaza at night.

30 Rockefeller Plaza at night. Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree

Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree Prometheus at Rockefeller Center

Prometheus at Rockefeller Center Channel Gardens at Rockefeller Center

Channel Gardens at Rockefeller Center

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Rockefeller Center". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 18, 2007.

- ↑ Pitts 1987

- ↑ NPS 1987

- ↑ "Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree Lighting".

- ↑ Okrent 2004, p. 70

- ↑ Glancy 1992, p. 431

- ↑ Seielstad 1930, p. 19

- ↑ Roussel 2006, p. 11

- ↑ "Rockefeller Center Art and History: 1930s". Rockefeller Center. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ Okrent 2004, p. 258.

- ↑ Okrent 2004, pp. 282–5.

- ↑ Okrent 2004, p. 411.

- ↑ Srodes 1999, pp. 207, 210

- ↑ The New York Times & June 3, 1993

- ↑ Rockefeller 2002, p. 479

- ↑ "About TODAY". Today.msnbc.msn.com. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ "75 Rockefeller Plaza - Time Warner Lease - Mohamed Al-Fayed". The Real Deal New York. 25 January 2012.

- ↑ David M Levitt (15 January 2013). "RXR Said to Buy 99-Year Leasehold at 75 Rockefeller Plaza". Bloomberg.com.

- ↑ "Ownership". 1211 Avenue of the Americas. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ The New York Times & December 11, 1988

- ↑ The New York Times & October 8, 1988.

- ↑ "Top of the Rock". Tishman Speyer. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Top of the Rock Observation Deck Information". NYCtourist.com. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ "WGBH American Experience . The Rockefellers | PBS". American Experience. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ↑ CNN, Laura Ma and Jason Kwok. "What are the world's best ice skating rinks?". CNN. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ↑ Popular Mechanics 1932, pp. 252–253

- ↑ Miller 2012

- ↑ "Rockefeller Center, New York City". VirtualTourist. March 13, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ Imagining Consumers: Design and Innovation from Wedgwood to Corning. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ↑ Kert 1993, pp. 352–365

- ↑ Reich 1996, pp. 105–111

- ↑ Roussel 2006, pp. 94–107.

- ↑ "The Rockefeller Archive Center - JDR Jr. Biographical Sketch". www.rockarch.org. Retrieved 2016-09-12.

Citations

- Blau, Eleanor (October 8, 1988). "Radio City Without Radio: WNBC Is Gone". The New York Times. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Dunlap, David W. (June 3, 1993). "G.E. Gives Midtown Tower To Columbia University". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Glancy, Dorothy J. (January 1, 1992). "Preserving Rockefeller Center". 24 Urb. Law. 423. Santa Clara University School of Law. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Kert, Bernice (October 12, 1993). Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-3945-6975-8. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Miller, Tom (November 28, 2012). "Rockefeller Center's David vs. Goliath -- No. 1240 6th Avenue". Daytonian in Manhattan. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Okrent, Daniel (November 30, 2004). Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0142001776. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Pitts, Carolyn (January 23, 1987). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- "World's Largest Theater in Rockefeller Center Will Seat Six Thousand Persons". Popular Mechanics. August 1932. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Reich, Cary (October 1, 1996). The Life of Nelson A. Rockefeller: Worlds to Conquer, 1908–1958. New York: Doubleday. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- "Rockefeller Center – Accompanying photos, c.1933 to c.1986" (PDF). National Park Service. January 23, 1987. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Rockefeller, David (October 15, 2002). Memoirs. New York: Random House. Retrieved March 6, 2014. (Subscription required (help)).

- Roussel, Christine (May 17, 2006). The Art of Rockefeller Center. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-3930-6082-9.

- Scardino, Albert (December 11, 1988). "Mitusi Unit Gets Exxon Building". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Seielstad, B.G. (September 1930). "Radio City to Cost $250,000,000". Popular Science Monthly. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Srodes, James (June 25, 1999). Allen Dulles: Master of Spies. Washington: Regnery Publishing, Inc. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

Further reading

- Balfour, Alan. Rockefeller Center: Architecture as Theater, New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1978.

- Deal, Martha. "Who Posed for the Statue of Prometheus" (Ray Van Cleef and Leon Nole). Iron Game History. Volume 6, Issue 4, Pages 34–35.

- Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988.

- Karp, Walter. The Center: A History and Guide to Rockefeller Center, New York: American Heritage Publishing Company, Inc., 1982.

- Krinsky, Carol H.. Rockefeller Center, New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Loth, David G. The City Within a City: The Romance of Rockefeller Center, New York: Morrow, 1966.

- Stichweh, Dirk. New York Skyscrapers, Munich: Prestel Publishing, 2009, ISBN 3-7913-4054-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rockefeller Center. |

- Official website

- Guide to Rockefeller Center

- The Rockefeller Group

- Rockefeller Center Webcam

- in-Arch.net: Rockefeller Center introduction

- The Rink at Rockefeller Center