Cigar

A cigar is a rolled bundle of dried and fermented tobacco leaf, produced in a variety of types and sizes to be smoked.

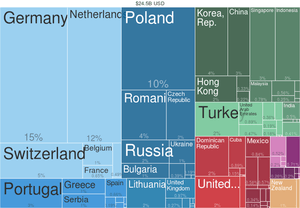

Cigar tobacco is grown in significant quantities primarily in Central America and the islands of the Caribbean, including Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Panama, and Puerto Rico; it is also produced in the Eastern United States, the Mediterranean countries of Italy and Spain (in the Canary Islands), and in Indonesia and the Philippines of Southeast Asia.

The origins of cigar smoking are still unknown. A Guatamalan ceramic pot dating back to the tenth century features a Mayan smoking tobacco leaves tied together with a string. Sikar, the Maya term for smoking, may have inspired the name cigar.[1]

Etymology

The word cigar originated from the Spanish cigarro, which in turn probably derives from the Mayan sicar ("to smoke rolled tobacco leaves" – from si'c, "tobacco"). There is also a possible derivation, or at least an influence, from the Spanish cigarra ("cicada"), due to their similar shape.[2] The English word came into general use in 1730.[3]

History

Explorer Christopher Columbus is generally credited with the introduction of tobacco to Europe. Three of Columbus's crewmen during his 1492 journey, Rodrigo de Jerez, Hector Fuentes and Luis de Torres, are said to have encountered tobacco for the first time on the island of Hispaniola, in what is present day Haiti and the Dominican Republic, when natives presented them with dry leaves that spread a peculiar fragrance. Tobacco was widely diffused among all of the islands of the Caribbean and therefore they again encountered it in Cuba where Columbus and his men had settled.[4] His sailors reported that the Taínos on the island of Cuba smoked a primitive form of cigar, with twisted, dried tobacco leaves rolled in other leaves such as palm or plantain.

In time, Spanish and other European sailors adopted the practice of smoking rolls of leaves, as did the Conquistadors, and smoking primitive cigars spread to Spain and Portugal and eventually France, most probably through Jean Nicot, the French ambassador to Portugal, who gave his name to nicotine. Later, tobacco use spread to Italy and, after Sir Walter Raleigh's voyages to the Americas, to Britain. Smoking became familiar throughout Europe—in pipes in Britain—by the mid-16th century. In 1542, tobacco started to be grown commercially in North America, when the Spaniards established the first cigar factory on the island of Cuba.[5] Tobacco was originally thought to have medicinal qualities, but there were some who considered it evil. It was denounced by Philip II of Spain and James I of England.[6]

Around 1592, the Spanish galleon San Clemente brought 50 kilograms (110 lb) of tobacco seed to the Philippines over the Acapulco-Manila trade route. It was distributed among Roman Catholic missionaries, who found excellent climates and soils for growing high-quality tobacco there.

In the 19th century, cigar smoking was common, while cigarettes were still comparatively rare. In the early 20th century, Rudyard Kipling wrote his famous smoking poem, "The Betrothed."

The cigar business was an important industry and factories employed many people before mechanized manufacturing of cigars became practical. Cigar workers in both Cuba and the US were active in labor strikes and disputes from early in the 19th century, and the rise of modern labor unions can be traced to the CMIU and other cigar worker unions.[7]

In 1869, Spanish cigar manufacturer Vicente Martinez Ybor moved his Principe de Gales (Prince of Wales) operations from the important cigar manufacturing center of Havana, Cuba to Key West, Florida to escape the turmoil of the Ten Years' War. Other manufacturers followed, and Key West became another important cigar manufacturing center. In 1885, Ybor moved again, buying land near the then-small city of Tampa, Florida and building the largest cigar factory in the world at the time[8] in the new company town of Ybor City. Friendly rival and Flor de Sánchez y Haya owner Ignacio Haya built his own factory nearby in the same year, and many other cigar manufacturers soon followed, especially after an 1886 fire that gutted much of Key West. Thousands of Cuban and Spanish tabaqueros came to the area from Key West, Cuba and New York to produce hundreds of millions of cigars annually. Local output peaked in 1929, when workers in Ybor City and West Tampa rolled over 500,000,000 "clear Havana" cigars, earning the town the nickname "Cigar Capital of the World".[9][10][11][12]

In New York, cigars were made by rollers working in their own homes. It was reported that as of 1883, cigars were being manufactured in 127 apartment houses in New York, employing 1,962 families and 7,924 individuals. A state statute banning the practice, passed late that year at the urging of trade unions on the basis that the practice suppressed wages, was ruled unconstitutional less than four months later. The industry, which had relocated to Brooklyn and other places on Long Island while the law was in effect, then returned to New York.[13]

As of 1905, there were 80,000 cigar-making operations in the United States, most of them small, family-operated shops where cigars were rolled and sold immediately.[9] While most cigars are now made by machine, some, as a matter of prestige and quality, are still rolled by hand---especially in Central America and Cuba, as well as in small chinchales in sizable cities in the United States.[9] Boxes of hand-rolled cigars bear the phrase totalmente a mano (totally by hand) or hecho a mano (made by hand). These premium hand-rolled cigars are significantly different from the machine-made cigars sold in packs at drugstores or gas stations. Since the 1990s there has been severe contention between producers and aficionados of premium handmade cigars and cigarette manufacturing companies that create machine-made cigars.

Manufacture

Tobacco leaves are harvested and aged using a curing process that combines heat and shade to reduce sugar and water content without causing the bigger leaves to rot. This takes between 25 and 45 days, depending upon climatic conditions and the nature of sheds or barns used to store harvested tobacco. Curing varies by type of tobacco and desired leaf color. A slow fermentation follows, where temperature and humidity are controlled to enhance flavor, aroma, and burning characteristics while forestalling rot or disintegration.

The leaf will continue to be baled, inspected, un-baled, re-inspected, and baled again during the aging cycle. When it has matured to manufacturer's specifications it is sorted for appearance and overall quality and used as filler or wrapper accordingly. During this process, leaves are continually moistened to prevent damage.

Quality cigars are still handmade.[14] An experienced cigar-roller can produce hundreds of very good, nearly identical, cigars per day. The rollers keep the tobacco moist — especially the wrapper — and use specially designed crescent-shaped knives, called chavetas, to form the filler and wrapper leaves quickly and accurately.[14] Once rolled, the cigars are stored in wooden forms as they dry, in which their uncapped ends are cut to a uniform size.[14] From this stage, the cigar is a complete product that can be "laid down" and aged for decades if kept as close to 21 °C (70 °F), and 70% relative humidity. Once purchased, proper storage is typically in a specialized wooden humidor.

Some cigars, especially premium brands, use different varieties of tobacco for the filler and the wrapper. Long filler cigars are a far higher quality of cigar, using long leaves throughout. These cigars also use a third variety of tobacco leaf, called a "binder", between the filler and the outer wrapper. This permits the makers to use more delicate and attractive leaves as a wrapper. These high-quality cigars almost always blend varieties of tobacco. Even Cuban long-filler cigars will combine tobaccos from different parts of the island to incorporate several different flavors.

In low-grade and machine-made cigars, chopped tobacco leaves are used for the filler, and long leaves or a type of "paper" made from tobacco pulp is used for the wrapper.[14] They alter the burning characteristics of the cigar vis-a-vis handmade cigars.

Historically, a lector or reader was always employed to entertain cigar factory workers. This practice became obsolete once audiobooks for portable music players became available, but it is still practiced in some Cuban factories. The name for the Montecristo cigar brand may have arisen from this practice.

Dominant manufacturers

Two firms dominate the cigar industry. Altadis produces cigars in the United States, the Dominican Republic, and Honduras, and has a 50% stake in Corporación Habanos in Cuba. It also makes cigarettes. Scandinavian Tobacco Group produces cigars in the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Nicaragua, Indonesia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark and the United States; it also makes pipe tobacco and fine cut tobacco. The Group includes General Cigar Co.[15]

Families in the cigar industry

Nearly all modern premium cigar makers are members of long-established cigar families, or purport to be. The art and skill of hand-making premium cigars has been passed from generation to generation; families are often shown in many cigar advertisements and packaging.[16]

In 1992, Cigar Aficionado magazine created the "Cigar Hall of Fame" and recognized the following six individuals:[17]

- Edgar M. Cullman, Chairman, General Cigar Company, New York, United States

- Zino Davidoff, Founder, Davidoff et Cie., Geneva, Switzerland

- Carlos Fuente, Sr., Chairman, Tabacalera A. Fuente y Cia., Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic

- Frank Llaneza, Chairman, Villazon & Co., Tampa, Florida, United States

- Stanford J. Newman, Chairman, J.C. Newman Cigar Company, Tampa, Florida, United States

- Ángel Oliva, Sr. (founder); Oliva Tobacco Co., Tampa, Florida, United States

Other families in the cigar industry (2015)

- Manuel Quesada (MATASA Current CEO) Fonseca, Casa Magna, Quesada cigars, Dominican Republic

- Don José "Pepín" Garcia, Chairman, El Rey de Los Habanos, Miami, Florida, United States

- Aray Family – Daniel Aray Jr, Grandson of Founder (1952) Jose Aray, ACC Cigars, Guayaquil Ecuador, San Francisco, CA, Miami Florida, Macau SAR, Shanghai China.

- EPC – Ernesto Perez-Carillo, Founder EPC Cigar Company (2009), Miami, Florida, United States

- Nestor Miranda – Founder, Miami Cigar Company (1989) Miami, FL, United States

Marketing and distribution

Pure tobacco, hand rolled cigars are marketed via advertisements, product placement in movies and other media, sporting events, cigar-friendly magazines such as Cigar Aficionado, and cigar dinners. Since handmade cigars are a premium product with a hefty price, advertisements often include depictions of affluence, sensual imagery, and explicit or implied celebrity endorsement.[18]

Cigar Aficionado, launched in 1992, presents cigars as symbols of a successful lifestyle, and is a major conduit of advertisements that do not conform to the tobacco industry's voluntary advertisement restrictions since 1965, such as a restriction not to associate smoking with glamour. The magazine also presents pro-smoking arguments at length, and argues that cigars are safer than cigarettes, since they do not have the thousands of chemical additives that cigarette manufactures add to the cutting floor scraps of tobacco used as cigarette filler. The publication also presents arguments that risks are a part of daily life and that (contrary to the evidence discussed in Health effects) cigar smoking has health benefits, that moderation eliminates most or all health risk, and that cigar smokers live to old age, that health research is flawed, and that several health-research results support claims of safety.[19] Like its competitor Smoke, Cigar Aficionado differs from marketing vehicles used for other tobacco products in that it makes cigars the focus of the entire magazine, creating a symbiosis between product and lifestyle.[20]

In the U.S., cigars are exempt from many of the marketing regulations that govern cigarettes. For example, the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act of 1970 exempted cigars from its advertising ban,[21] and cigar ads, unlike cigarette ads, need not mention health risks.[18] As of 2007, cigars were taxed far less than cigarettes, so much so that in many U.S. states, a pack of little cigars cost less than half as much as a pack of cigarettes.[21] It is illegal for minors to purchase cigars and other tobacco products in the U.S., but laws are unevenly enforced: a 2000 study found that three-quarters of web cigar sites allowed minors to purchase them.[22]

Inexpensive, non-pure cigars are sold in convenience stores, gas stations, grocery stores, and pharmacies, mostly as self-serve items. Premium cigars are sold in tobacconists, cigar bars, and other specialized establishments.[23] Some cigar stores are part of chains, which have varied in size: in the U.S., United Cigar Stores was one of only three outstanding examples of national chains in the early 1920s, the others being A&P and Woolworth's.[24] Non-traditional outlets for cigars include hotel shops, restaurants, vending machines[23] and the Internet.[22]

Composition

Cigars are composed of three types of tobacco leaves, whose variations determine smoking and flavor characteristics:

Wrapper

A cigar's outermost layer, or wrapper (Spanish: capa), is the most expensive component of a cigar.[25] The wrapper determines much of the cigar's character and flavor, and as such its color is often used to describe the cigar as a whole. Wrappers are frequently grown underneath huge canopies made of gauze so as to diffuse direct sunlight and are fermented separately from other rougher cigar components, with a view to the production of a thinly-veined, smooth, supple leaf.[25]

Wrapper tobacco produced without the gauze canopies under which "shade grown" leaf is grown, generally more coarse in texture and stronger in flavor, is commonly known as "sun grown." A number of different countries are used for the production of wrapper tobacco, including Cuba, Ecuador, Indonesia, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Brazil, Mexico, Cameroon, and the United States.[25]

While dozens of minor wrapper shades have been touted by manufacturers, the seven most common classifications are as follows,[26] ranging from lightest to darkest:

| Color | Description |

|---|---|

| Candela ("Double Claro") | very light, slightly greenish. Achieved by picking leaves before maturity and drying quickly, the color coming from retained green chlorophyll. |

| Claro | very light tan or yellowish |

| Colorado Claro | medium brown |

| Colorado ("Rosado") | reddish-brown |

| Colorado Maduro | darker brown |

| Maduro | very dark brown |

| Oscuro ("Double Maduro") | black |

Some manufacturers use an alternate designation:

| Designation | Acronym | Description |

|---|---|---|

| American Market Selection | AMS | synonymous with Candela ("Double Claro") |

| English Market Selection | EMS | any natural colored wrapper which is darker than Candela but lighter than Maduro[27] |

| Spanish Market Selection | SMS | one of the two darkest colors, Maduro or Oscuro |

In general, dark wrappers add a touch of sweetness, while light ones add a hint of dryness to the taste.

Binder

Beneath the wrapper is a small bunch of "filler" leaves bound together inside of a leaf called a "binder" (Spanish: capote). Binder leaf is typically the sun-saturated leaf from the top part of a tobacco plant and is selected for its elasticity and durability in the rolling process.[25] Unlike wrapper leaf, which must be uniform in appearance and smooth in texture, binder leaf may show evidence of physical blemishes or lack uniform coloration. Binder leaf is generally considerably thicker and more hardy than the wrapper leaf surrounding it.

Filler

The bulk of a cigar is "filler" — a bound bunch of tobacco leaves. These leaves are folded by hand to allow air passageways down the length of the cigar, through which smoke is drawn after the cigar is lit.[25] A cigar rolled with insufficient air passage is referred to by a smoker as "too tight"; one with excessive airflow creating an excessively fast, hot burn is regarded as "too loose." Considerable skill and dexterity on the part of the cigar roller is needed to avoid these opposing pitfalls — a primary factor in the superiority of hand-rolled cigars over their machine-made counterparts.[25]

By blending various varieties of filler tobacco, cigar makers create distinctive strength and flavor profiles for their various branded products. In general, fatter cigars hold more filler leaves, allowing a greater potential for the creation of complex flavors. In addition to the variety of tobacco employed, the country of origin can be one important determinant of taste, with different growing environments producing distinctive flavors.

The fermentation and aging process adds to this variety, as does the particular part of the tobacco plant harvested, with bottom leaves (Spanish: volado) having a mild flavor and burning easily, middle leaves (Spanish: seco) having a somewhat stronger flavor, with potent and spicy ligero leaves taken from the sun-drenched top of the plant. When used, ligero is always folded into the middle of the filler bunch due to its slow-burning characteristics.

If full leaves are used as filler, a cigar is said to be composed of "long filler." Cigars made from smaller bits of leaf, including many machine-made cigars, are said to be made of "short filler."

If a cigar is completely constructed (filler, binder, and wrapper) of tobacco produced in only one country, it is referred to in the cigar industry as a "puro," from the Spanish word for "pure."

Size and shape

Cigars are commonly categorized by their size and shape, which together are known as the vitola.

The size of a cigar is measured by two dimensions: its ring gauge (its diameter in sixty-fourths of an inch) and its length (in inches). In Cuba, next to Havana, there is a display of the world's longest rolled cigars.

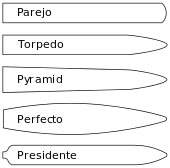

Parejo

The most common shape is the parejo, sometimes referred to as simply "coronas", which have traditionally been the benchmark against which all other cigar formats are measured. They have a cylindrical body, straight sides, one end open, and a round tobacco-leaf "cap" on the other end which must be sliced off, have a V-shaped notch made in it with a special cutter, or punched through before smoking.

Parejos are designated by the following terms:

| Term | Length in inches | Width in 64ths of an inch | Metric length | Metric width | Etymology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarillo | ~ 3½ | ~ 21 | ~ 8 cm | ~ 8 mm | Sizes may vary significantly. According to CigarCyclopedia, cigarillo is shorter than 6 inches (15 cm) and narrower than 29 (11.5 mm).[28] |

| Rothschild | 4½ | 48 | 11 cm | 19 mm | after the Rothschild family |

| Robolo | 4½ | 60 | 11 cm | 24 mm | |

| Robusto | 4⅞ | 50 | 12 cm | 20 mm | |

| Small Panatella | 5 | 33 | 13 cm | 13 mm | |

| Ascot | 4½ | 24 | 11 cm | 13 mm | |

| Petit Corona | 5⅛ | 42 | 13 cm | 17 mm | |

| Carlota | 5⅝ | 35 | 14 cm | 14 mm | |

| Corona | 5½ | 42 | 14 cm | 17 mm | |

| Corona Gorda | 5⅝ | 46 | 14 cm | 18 mm | |

| Panatella | 6 | 38 | 15 cm | 15 mm | |

| Toro | 6 | 50 | 15 cm | 20 mm | |

| Corona Grande | 6⅛ | 42 | 16 cm | 17 mm | |

| Lonsdale | 6½ | 42 | 17 cm | 17 mm | named for Hugh Cecil Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale |

| Churchill | 7 | 47–50 | 18 cm | 19–20 mm | named for Sir Winston Churchill |

| Double Corona | 7⅝ | 49 | 19 cm | 19 mm | |

| Presidente | 8 | 50 | 20 cm | 20 mm | |

| Gran Corona | 9¼ | 47 | 23 cm | 19 mm | |

| Double Toro/Gordo | 6 | 60 | 15 cm | 24 mm |

These dimensions are, at best, idealized. Actual dimensions can vary considerably.

Figurado

Irregularly shaped cigars are known as figurados and are sometimes considered of higher quality because they are more difficult to make.

Historically, especially during the 19th century, figurados were the most popular shapes, but by the 1930s they had fallen out of fashion and all but disappeared. They have, however, recently received a small resurgence in popularity, and there are currently many brands (manufacturers) that produce figurados alongside the simpler parejos. The Cuban cigar brand Cuaba only has figurados in their range.

Figurados include the following:

| Figurado | Description |

|---|---|

| Torpedo | Like a parejo except that the cap is pointed |

| Cheroot | Like a parejo except that there is no cap, i.e. both ends are open |

| Pyramid | Has a broad foot and evenly narrows to a pointed cap |

| Perfecto | Narrow at both ends and bulged in the middle |

| Presidente/Diadema | shaped like a parejo but considered a figurado because of its enormous size and occasional closed foot akin to a perfecto |

| Culebras | Three long, pointed cigars braided together |

| Chisel | Is much like the Torpedo, but instead of coming to a rounded point, comes to a flatter, broader edge, much like an actual chisel. This shape was patented and can only be found in the La Flor Dominicana (LFD) brand |

Arturo Fuente, a large cigar manufacturer based in the Dominican Republic, has also manufactured figurados in exotic shapes ranging from chilli peppers to baseball bats and American footballs. They are highly collectible and extremely expensive, when available to the public. In practice, the terms Torpedo and Pyramid are often used interchangeably, even among very knowledgeable cigar smokers. Min Ron Nee, the Hong Kong-based cigar expert whose work An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Post-Revolution Havana Cigars is considered to be the definitive work on cigars and cigar terms, defines Torpedo as "cigar slang". Nee thinks the majority is right (because slang is defined by majority usage) and torpedoes are pyramids by another name.

Cigarillo

A cigarillo is a machine-made cigar that is shorter and narrower than a traditional cigar but larger than little cigars,[29] filtered cigars, and cigarettes, thus similar in size and composition to small panatela sized cigars, cheroots, and traditional blunts. Cigarillos are usually not filtered, although some have plastic or wood tips, and are not meant to be inhaled. They are sold in varying quantities: singles, two-packs, three-packs, and five-packs. Cigarillos are very inexpensive: in the United States, usually sold for less than a dollar. Sometimes they are informally called small cigars, mini cigars, or club cigars. Some famous cigar brands, such as Cohiba or Davidoff, also make cigarillos---Cohiba Mini and Davidoff Club Cigarillos, for example. And there are purely cigarillo brands, such as Café Crème, Dannemann Moods, Mehari's, Al Capone, and Swisher Sweets. Cigarillos have a secondary use: they are often used for the making of marijuana cigars.

Little cigars

Little cigars (sometimes called small cigars or miniatures in the UK) differ greatly from regular cigars.[29] They weigh less than cigars and cigarillos,[30] but, more importantly, they resemble cigarettes in size, shape, packaging, and filters.[31] Sales of little cigars quadrupled in the U.S. from 1971 to 1973 in response to the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act, which banned the broadcast of cigarette advertisements and required stronger health warnings on cigarette packs. Cigars were exempt from the ban, and perhaps more importantly, were taxed at a far lower rate. Little cigars are sometimes called "cigarettes in disguise", and unsuccessful attempts have been made to reclassify them as cigarettes. In the United States, sales of little cigars reached an all-time high in 2006, fueled in great part by favorable taxation.[21] In some states, however, little cigars have successfully been taxed at the rate of cigarettes, such as Illinois,[32] as well as multiple other states. This has caused yet another loophole, in which manufacturers classify their products as "filtered cigars" instead to avoid the higher tax rate. Yet, many continue to argue that there is in fact a distinction between little cigars and filtered cigars. Little cigars offer a similar draw and overall feel to cigarettes, but with aged and fermented tobaccos, while filtered cigars are said to be more closely related to traditional cigars, and are not meant to be inhaled.[33]

Smoking

To smoke a cigar, a smoker cuts the closed end or 'cap', lights the other end, then puts the unlit end into the mouth and draws smoke into the mouth. Some smokers inhale the smoke into the lungs, particularly with little cigars, but this is uncommon otherwise. A smoker may swirl the smoke around in the mouth before exhaling it, and may exhale part of the smoke through the nose in order to smell the cigar better as well as to taste it.

Cutting

Although some cigars are cut on both ends, or twirled at both ends, the vast majority come with one straight cut end and one end in a "cap". Most quality handmade cigars, regardless of shape, will have a cap which is one or more small pieces of a wrapper pasted onto one end of the cigar with either a natural tobacco paste or with a mixture of flour and water. The cap end of a cigar must be cut for the cigar to be smoked properly. It is the rounded end without the tobacco exposed and the end to always cut. If the cap is cut jaggedly or without care, the end of the cigar will not burn evenly and smokeable tobacco will be lost. Some cigar manufacturers purposely place different types of tobacco from one end to the other to give the cigar smokers a variety of tastes, body, and strength from start to finish.

There are three basic types of cigar cutters:

- Guillotine (straight cut)

- Punch cut

- V-cut (a.k.a. notch cut, cat's eye, wedge cut, English cut)

Lighting

The "head" of the cigar is usually the end closest to the cigar band. The opposite end of the cigar is called the "foot". The band identifies the type of the cigar and may be removed or left on. The smoker cuts the cap from the head of the cigar and ignites the foot of the cigar. The smoker draws smoke from the head of the cigar with the mouth and lips, usually not inhaling into the lungs.

When lighting, the cigar should be rotated to achieve an even burn and the air should be slowly drawn with gentle puffs. A flame that may impart its own flavor to the cigar should not be used. The tip of the cigar should minimally touch the flame, the heat of the flame from a butane or torch lighter can burn the tobacco leaves. A match or cedar spill flame is a milder flame to be used.

Cigars can be lit with the use of butane-filled lighters. Butane is colorless, odorless and burns clean with very little, if any, flavor; but are quite hot as a flame source. It is not recommended to use (lighter) fluid-filled lighters and paper matches since they can influence the taste.

A second option is wooden matches, but the smoker must ensure the chemical head of the match has burned away and only the burning wooden section is used to light the cigar. Depending on the manufacturer, the chemical head portion of the matchstick may contain one or more of the following: gelatin, paraffin wax, potassium chlorate, barium chlorate, glue, polyvinyl chlorides, phosphorus trisulfide, and clay. The strike plate to ignite the match may contain one more of the following: glass particles, red phosphorus, and glue.

A third and most traditional way to light a cigar is to use a cedar spill. A spill is a splinter or a slender piece of wood or twisted paper, for lighting candles, lamps, campfires or fireplaces, etc. A cedar spill for lighting a cigar is a torn narrow strip of Spanish cedar (ideally) and lit using whatever flame source is handy.[34]

Cigars packaged in boxes or metal tubes may contain a thin wrapping of cedar that may be used to light a cigar, minimizing the problem of lighters or matches affecting the taste. Cedar spills, matches, and lighters are all commercially available.

Flavor

Each brand and type of cigar tastes different. While the wrapper does not entirely determine the flavor of the cigar, darker wrappers tend to produce a sweetness, while lighter wrappers usually have a "drier" taste.[14] Whether a cigar is mild, medium, or full bodied does not correlate with quality. Some words used to describe cigar flavor and texture include; spicy, peppery (red or black), sweet, harsh, burnt, green, earthy, woody, cocoa, chestnut, roasted, aged, nutty, creamy, cedar, oak, chewy, fruity, and leathery.

Cigar smoke, which is not typically inhaled, tastes of tobacco with nuances of other tastes. Many different things affect the scent of cigar smoke: tobacco type, quality of the cigar, added flavors, age and humidity, production method (handmade vs. machine-made), and more.[14] A fine cigar can taste completely different from inhaled cigarette smoke. When smoke is inhaled, as is usual with cigarettes, the tobacco flavor is less noticeable than the sensation from the smoke. Some cigar enthusiasts use a vocabulary similar to that of wine-tasters to describe the overtones and undertones observed while smoking a cigar. Journals are available for recording personal ratings, description of flavors observed, sizes, brands, etc. Cigar smoking is in such respects similar to wine-tasting.

Smoke

Smoke is produced by incomplete combustion of tobacco during which at least three kinds of chemical reactions occur: pyrolysis breaks down organic molecules into simpler ones, pyrosynthesis recombines these newly formed fragments into chemicals not originally present, and distillation moves compounds such as nicotine from the tobacco into the smoke. For every gram of tobacco smoked, a cigar emits about 120–140 mg of carbon dioxide, 40–60 mg of carbon monoxide, 3–4 mg of isoprene, 1 mg each of hydrogen cyanide and acetaldehyde, and smaller quantities of a large spectrum of volatile N-nitrosamines and volatile organic compounds, with the detailed composition unknown.[35]

The most odorous chemicals in cigar smoke, and arguably the most responsible for the odor, are pyridines. Along with pyrazines, they are also the most odorous chemicals in cigar smokers' breath. These substances are noticeable even at extremely low concentrations of a few parts per billion. During smoking, it is not known whether these chemicals are generated by splitting the chemical bonds of nicotine or by Maillard reaction between amino acids and sugars in the tobacco.[36]

Cigar smoke is more alkaline than cigarette smoke, and therefore dissolves and is absorbed more readily by the mucous membrane of the mouth, making it easier for the smoker to absorb nicotine without having to inhale.[37]

Humidors

The level of humidity in which cigars are kept has a significant effect on their taste. It is believed that a cigar's flavor best evolves when stored at a relative humidity of approximately 65–70% and a temperature of 18 °C (64 °F).[38] An ideal rate of humidity allows an even burning of the cigar. Conversely, dry cigars become fragile and burn faster while damp cigars burn unevenly and take on a heavy acidic flavor. Humidors together with their humidifiers are then used to serve this purpose. Without a humidor, within 2 to 3 days, cigars will quickly lose moisture and level up with the general humidity around them.[39] A humidor's interior lining is typically constructed with three types of wood: Spanish cedar, American (or Canadian) red cedar, and Honduran mahogany. Other materials used for making or lining a humidor are Acrylic, Tin ( mainly seen in older early humidors) and Copper, used widely in the 1920s-1950s.

Most humidors come with a plastic or metal case with a sponge that works as the humidifier, although most recent versions are of polymer acryl. The latter are filled only with distilled water; the former may use a solution of propylene glycol and distilled water. Humidifiers may become contaminated with bacteria and should be replaced every two years to avoid such contamination. There are new methods and devices for humidification that keep the relative humidity at a constant. These devices come in the former of small, medium, and large packets, with beads in a container which, when water is added, absorb the moisture.

Humidors also come with analog or digital hygrometers. There are three systems of analog hygrometers: analog hygrometers with a metal spring, analog natural hair hygrometers, and analog synthetic hair hygrometers.[40]

A new humidor requires seasoning and once seasoned needs to have its humidity maintained in some fashion. The inside of a humidor should be lined in dried Spanish cedar wood. The thicker the lining the better as it will provide the best environment for the cigars. The internal wood of a new humidor will not contain much moisture. The inside needs to be seasoned: allowing it to absorb moisture so that it can maintain the desired humidity level. There are many methods to season a humidor but the most common is to fill up a shot glass with distilled water, place it into the humidor, close it up, and let it sit for two weeks, checking on it every couple of days. Any method you use that consists of using water, you should use distilled water so that you are using something with the least amount of impurities. There are also seasoning packs that you can use from companies like Boveda if you choose to go that route instead of using water.[41]

Accessories

There are a wide variety of cigar accessories on the market. Their prices may vary depending on the materials used and the quality of the finishing.

Cigar travel cases

Travel cases are intended to protect cigars from the environmental elements and to avoid the possibility of cigars being crushed. Most travel cases come in expandable or sturdy leather. They should be thick enough to protect cigars, and the inside should not have a strong leather smell that could affect the cigar's taste. Some of these cases come with either cardboard or metal tubes that add protection and prevent the cigar from becoming permeated with the leather. Silver and brass cigar travel cases are also available as well as wood cigar cases. The latter can range from affordable cases to handcrafted ones, while the former tend to be quite expensive.

Cigar tubes

Cigar tubes are used to carry small numbers of cigars, typically one or five. The latter tube would be called 5-finger tube and the former 1-finger tube. They are usually made from stainless steel. Cigar tubes are normally used when one is out for a few hours, but if it is necessary to spend longer periods of time out, there are tubes that come with a built in humidifier and hygrometer.

Cigar holders

Cigar holders are also known as cigar stands and are used to keep the cigars out of ashtrays. Also, cigar holders may refer to a tube in which the cigar is held while smoked. These are mostly used by women, and rarely by men.

Health effects

Like other forms of tobacco use, cigar smoking poses a significant health risk depending on dosage: risks are greater for those who inhale more when they smoke, smoke more cigars, or smoke them longer.[42] The risk of dying from any cause is statistically greater for cigar smokers than for people who have never smoked, with the risk higher for smokers less than 65 years old, and with risk for moderate and deep inhalers reaching levels similar to cigarette smokers.[43] According to one study published in 1999 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, current cigar users have shown a statistically significant, elevated mortality risk for cancers of the mouth, lungs, and larynx and a moderately elevated risk for cancer of the esophagus, though this study assumed deep inhalation and multiple cigars per day, which is not typical of the traditional cigar smoker.[44] No comparable statistical link was found for pancreatic or bladder cancer mortality in this study.[44]

Danger of mortality increases proportionally to consumption, with smokers of one to two cigars per day showing a 2% increase in rate of mortality through all causes compared to non-smokers.[45] The precise statistical health risks to those cigar smokers who smoke less than daily is not established.[46]

The depth of inhalation of cigar smoke into the lungs appears to be an important determinant of lung cancer risk:

"When cigar smokers don't inhale or smoke few cigars per day, the risks are only slightly above those of never smokers. Risks of lung cancer increase with increasing inhalation and with increasing number of cigars smoked per day, but the effect of inhalation is more powerful than that for number of cigars per day. When 5 or more cigars are smoked per day and there is moderate inhalation, the lung cancer risks of cigar smoking approximate those of a one pack per day cigarette smoker. As the tobacco smoke exposure of the lung in cigar smokers increases to approximate the frequency of smoking and depth of inhalation found in cigarette smokers, the difference in lung cancer risks produced by these two behaviors disappears."[47]

Cigar smoking can lead to nicotine addiction and cigarette usage.[43][48] For those who inhale and smoke several cigars a day, types of health risk can be similar to those associated with cigarette smoking: nicotine addiction, periodontal disease, tooth loss, and many types of cancer, including cancers of the mouth, throat, and esophagus.[48] Cigar smoking can also increase the risk of lung and heart diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[42][48]

So-called "little cigars" are commonly inhaled and likely pose the same health risks as cigarettes, while premium cigars are not commonly inhaled or habitually used.[49]

Popularity

The prevalence of cigar smoking varies depending on location, historical period, and population surveyed, and prevalence estimates vary somewhat depending on the survey method. The U.S. is the top consuming country by far, followed by Germany and the UK; the U.S. and western Europe account for about 75% of cigar sales worldwide.[15] The 2005 U.S. National Health Interview Survey estimated that 2.2% of adults smoke cigars, about the same as smokeless tobacco but far less than the 21% of adults who smoke cigarettes; it also estimated that 4.3% of men but only 0.3% of women smoke cigars.[50] A 2007 California study found that gay men and bisexual women smoke significantly fewer cigars than the general population of men and women, respectively.[51] Substantial and steady increases in cigar smoking were observed during the 1990s and early 2000s in the U.S. among both adults and adolescents.[31] Data suggest that cigar usage among young adult males increased threefold during the 1990s, a 1999–2000 survey of 31,107 young adult U.S. military recruits found that 12.3% smoked cigars,[52] and a 2003–2004 survey of 4,486 high school students in a Midwestern county found that 18% smoked cigars.[53] Recent CDC Youth Risk surveys show a decline in tobacco use, and does not distinguish between premium and little cigar usage. It is assumed that premium cigar use among adolescents is negligible.[54]

Cuban cigars

Cuban cigars are rolled from tobacco leaves found throughout the country of Cuba. The filler, binder, and wrapper may come from different portions of the island. All cigar production in Cuba is controlled by the Cuban government, and each brand may be rolled in several different factories in Cuba.

Torcedores are highly respected in Cuban society and culture, and they travel worldwide displaying their art of hand rolling cigars.[55]

Habanos SA and Cubatabaco between them do all the work relating to Cuban cigars, including manufacture, quality control, promotion and distribution, and export. Cuba produces both handmade and machine-made cigars. All boxes and labels are marked Hecho en Cuba (Spanish for made in Cuba). Machine-bunched cigars finished by hand add Hecho a mano, while fully handmade cigars say Totalmente a mano in script text, though not all Cuban cigars will include this statement. Because of the perceived status of Cuban cigars, counterfeits are somewhat commonplace.[56]

Despite American trade sanctions against Cuban products, cigars remain one of the country's leading exports. The country exported 77 million cigars in 1991, 67 million in 1992, and 57 million in 1993, the decline attributed to a loss of much of the wrapper crop in a hurricane.[57]

United States embargo against Cuba

On 7 February 1962, United States President John F. Kennedy imposed a trade embargo on Cuba to sanction Fidel Castro's communist government. According to Pierre Salinger, then Kennedy's press secretary, the president ordered him on the evening of 6 February to obtain 1,200 H. Upmann brand Petit Upmann Cuban cigars; upon Salinger's arrival with the cigars the following morning, Kennedy signed the executive order which put the embargo into effect.[59] Richard Goodwin, a White House assistant to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, revealed in a 2000 New York Times article that in early 1962, JFK told him, "We tried to exempt cigars, but the cigar manufacturers in Tampa objected."[60]

The embargo prohibited U.S. residents from legally purchasing Cuban cigars and American cigar manufacturers from importing Cuban tobacco. As a result, Cuba was deprived of its major customer for tobacco, and American cigar manufacturers either had to find an alternative source of tobacco or go out of business.[61]

Upon the expropriation of private property in Cuba, many former Cuban cigar manufacturers moved to other countries (primarily the Dominican Republic) to continue production.[62] The Dominican Republic's production of tobacco grew significantly as a result.[63] After reallocation, most Cuban manufacturers continued to use their known company name, seed, and harvesting technique while Cubatabaco, Cuba's state tobacco monopoly after the Revolution, independently continued production of cigars using the former private company names.[62] As a result, cigar name brands like Romeo y Julieta, La Gloria Cubana, Montecristo, and H. Upmann among others, exist in both Cuba and the Dominican Republic.[64] Honduras and Nicaragua are also mass manufacturers of cigars. Some Cuban refugees make cigars in the U.S. and advertise them as "Cuban" cigars, using the argument that the cigars are made by Cubans.[65]

While Cuban cigars are smuggled into the U.S. and sold at high prices, counterfeiting is rife; it has been said that 95% of Cuban cigars sold in the U.S. are counterfeit.[66] Although Cuban cigars cannot legally be imported into the U.S., the advent of the Internet has made it much easier for people in the United States to purchase cigars online from other countries, especially when shipped without bands. Cuban cigars are openly advertised in some European tourist regions, catering to the American market, even though it is illegal to advertise tobacco in most European regions.[67]

The loosening of the embargo in January 2015 included a provision that allowed the importation into the U.S. of up to $100 worth of alcohol or tobacco per traveler, allowing legal importation for the first time since the ban.[68] In October 2016, the Obama administration lifted restrictions on the number of cigars that an American can bring back to the U.S. for personal use without having to pay customs taxes.[69]

In popular culture

In the 1980s and 1990s, major U.S. print media portrayed cigars favorably; they generally framed cigar use as a lucrative business or a trendy habit, rather than as a health risk.[70] Rich people are often caricatured as wearing top hats and tails and smoking cigars. Cigars are often smoked to celebrate special occasions: the birth of a child, a graduation, a big sale. The expression "close but no cigar" comes from the practice of giving cigars as prizes in games involving good aim at fairgrounds.

Celebrity Cigar Smoker of the Year Award

In 2013 the UK magazine The Spectator inaugurated an International Celebrity Cigar Smoker of the Year Award. Since 2015 the event has been sponsored by Snow Queen Vodka.

The first winner, in 2013, was Simon le Bon. In 2014, Arnold Schwarzenegger became the second winner,[71] Jonathan Ross won in 2015 and Kelsey Grammer in 2016.[72]

See also

- Box-pressed

- Cabinet selection

- Catador

- Cigar etiquette

- Cigar makers strike of 1877

- List of cigar brands

- Smoking jacket

Footnotes

- ↑ Altman, Alex (2 January 2009). "A Brief History Of the Cigar". TIME. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cigar". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 364.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cigar". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 364. - ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ Van Lancker JL (1977). "Smoking and disease" (PDF). NIDA Res Monogr (17): 230–88. PMID 417256.

- ↑ The History of Cigars in the Old World

- ↑ "A bit of History". Cigars Review. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ↑ Lerman, N. (ed.) Gender and Technology: A Reader, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801872596 (2003), pp. 212-213

- ↑ "Florida State Parks". Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Frank, Michael "Wise old hands", ''Cigar Aficionado'' (Winter 1993)". Cigaraficionado.com. 1 December 1993. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ Ingalls, Robert (2003). Tampa Cigar Workers: A Pictorial History. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2602-4.

- ↑ Jamison, Gayla (Producer, Director, Writer) (1987). Living in America: 100 Years of Ybor City (video documentary). Tampa, Fl: Lightfoot Films, Inc.

- ↑ Lastra, Frank (2006). Ybor City: The Making of a Landmark Town. University of Tampa Press. ISBN 1-59732-003-X.

- ↑ ""Tenement cigar making", ''New York Times'' (January 30, 1884)". New York Times. 30 January 1884. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Butcher, Vernon A. (1949). The Cigar. Orange, New Jersey: Standard Press. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); - 1 2 Rarick CA (2 April 2008). "Note on the premium cigar industry". SSRN. SSRN 1127582

.

. - ↑ "The Change at C.A.O. | Cigar Stars". Cigar Aficionado. 1 April 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ "Cigar Aficionado Magazine Cigar Hall of Fame". Cigaraficionado.com. 1 December 2002. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- 1 2 Baker F, Ainsworth SR, Dye JT, et al. (2000). "Health risks associated with cigar smoking". JAMA. 284 (6): 735–40. PMID 10927783. doi:10.1001/jama.284.6.735.

- ↑ DeSantis AD, Morgan SE (2003). "Sometimes a cigar [magazine] is more than just a cigar [magazine]: pro-smoking arguments in Cigar Aficionado, 1992–2000". Health Commun. 15 (4): 457–80. PMID 14557079. doi:10.1207/S15327027HC1504_05.

- ↑ Wenger LD, Malone RE, George A, Bero LA (2001). "Cigar magazines: using tobacco to sell a lifestyle". Tob Control. 10 (3): 279–84. PMC 1747592

. PMID 11544394. doi:10.1136/tc.10.3.279.

. PMID 11544394. doi:10.1136/tc.10.3.279. - 1 2 3 Delnevo CD, Hrywna M (2007). "'A whole 'nother smoke' or a cigarette in disguise: how RJ Reynolds reframed the image of little cigars". Am J Public Health. 97 (8): 1368–75. PMC 1931466

. PMID 17600253. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.101063.

. PMID 17600253. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.101063. - 1 2 Malone RE, Bero LA (2000). "Cigars, youth, and the Internet link" (PDF). Am J Public Health. 90 (5): 790–2. PMC 1446234

. PMID 10800432. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.5.790.

. PMID 10800432. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.5.790. - 1 2 Slade J (1998). "Marketing and promotion of cigars" (PDF). In Shopland DR, Burns DM, Hoffman D, Cummings KM, Amacher RH. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends (PDF). Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9. National Cancer Institute. pp. 195–219. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ↑ Hayward WS, White P, Fleek HS, Mac Intyre H (1922). "The chain store field". Chain Stores: Their Management and Operation. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 16–31. OCLC 255149441.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Anwer Bati, The Cigar Companion: The Connoisseur's Guide. Third Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Running Press, 1997; pg. 27.

- ↑ Richard Perelman, Perelman's Pocket Cyclopedia of Cigars. Perelman, Pioneer & Co., 2004; pg. 12.

- ↑ "Wrappers," The Cigarbox.net, retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ http://www.cigarcyclopedia.com/images/stories/cigarcyclopedia/10_basics-111409.pdf

- 1 2 "Legacy eNews – January 2010 (UPDATED)". Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ Connolly GN (1998). "Policies regulating cigars" (PDF). In Shopland DR, Burns DM, Hoffman D, Cummings KM, Amacher RH. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends (PDF). Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9. National Cancer Institute. pp. 221–32. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- 1 2 Delnevo CD (2006). "Smokers' choice: what explains the steady growth of cigar use in the U.S.?" (PDF). Public Health Rep. 121 (2): 116–9. PMC 1525261

. PMID 16528942.

. PMID 16528942. - ↑ "Illinois Explains New Sales Tax on Little Cigars - TaxRates.com". TaxRates.com. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ "Filtered and Little Cigars". Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ Lighting Cigars Article, Cigars4Dummies, 2009

- ↑ Hoffmann D, Hoffmann I (1998). "Chemistry and toxicology" (PDF). In Shopland DR, Burns DM, Hoffman D, Cummings KM, Amacher RH. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends (PDF). Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9. National Cancer Institute. pp. 55–104. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ↑ Bazemore R, Harrison C, Greenberg M (2006). "Identification of components responsible for the odor of cigar smoker's breath". J Agric Food Chem. 54 (2): 497–501. PMID 16417311. doi:10.1021/jf0519109.

- ↑ Viegas CA (2008). "Noncigarette forms of tobacco use". J Bras Pneumol. 34 (12): 1069–73. PMID 19180343. doi:10.1590/S1806-37132008001200013.

- ↑ "How to store cigars, humidor care, cigar care". Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ "How long do cigars last without a humidor?". Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ↑ "Humidor Guide". Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ↑ http://blindmanspuff.com/choosing-seasoning-humidor/

- 1 2 Symm B, Morgan MV, Blackshear Y, Tinsley S (2005). "Cigar smoking: an ignored public health threat". J Prim Prev. 26 (4): 363–75. PMID 15995804. doi:10.1007/s10935-005-5389-z.

- 1 2 Shanks TG, Burns DM (1998). "Disease consequences of cigar smoking" (PDF). In Shopland DR, Burns DM, Hoffman D, Cummings KM, Amacher RH. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends (PDF). Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9. National Cancer Institute. pp. 105–160. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- 1 2 Jean A. Shapiro, Eric J. Jacobs and Michael J. Thun, "Cigar Smoking in Men and Risk of Death From Tobacco-Related Cancers," Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 92, no. 4 (2000), pp. 333–337.

- ↑ David M. Burns, "Cigar Smoking: Overview and Current State of the Science," Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph, No. 9. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 1998; NIH publication no. 98-4302; pg. 6.

- ↑ "Questions and answers about cigar smoking and cancer". National Cancer Institute. 7 March 2000. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ↑ Burns, "Cigar Smoking: Overview and Current State of the Science," pg. 8.

- 1 2 3 Burns DM (1998). "Cigar smoking: overview and current state of the science" (PDF). In Shopland DR, Burns DM, Hoffman D, Cummings KM, Amacher RH. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends (PDF). Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9. National Cancer Institute. pp. 8, 1–20. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Dollar KM, Mix JM, Kozlowski LT (2008). "Little cigars, big cigars: omissions and commissions of harm and harm reduction information on the Internet". Nicotine Tob Res. 10 (5): 819–26. PMID 18569755. doi:10.1080/14622200802027214.

- ↑ Mariolis P, Rock VJ, Asman K, et al. (2006). "Tobacco use among adults—United States, 2005". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 55 (42): 1145–8. PMID 17065979.

- ↑ Gruskin EP, Greenwood GL, Matevia M, Pollack LM, Bye LL, Albright V (2007). "Cigar and smokeless tobacco use in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual population". Nicotine Tob Res. 9 (9): 937–40. PMID 17763109. doi:10.1080/14622200701488426.

- ↑ Vander Weg MW, Peterson AL, Ebbert JO, Debon M, Klesges RC, Haddock CK (2008). "Prevalence of alternative forms of tobacco use in a population of young adult military recruits". Addict Behav. 33 (1): 69–82. PMC 2101765

. PMID 17706889. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.005.

. PMID 17706889. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.005. - ↑ Brooks A, Gaier Larkin EM, Kishore S, Frank S (2008). "Cigars, cigarettes, and adolescents". Am J Health Behav. 32 (6): 640–9. PMID 18442343. doi:10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.6.640.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/us_tobacco_combo.pdf

- ↑ RIVERA, Maricarmen (29 April 2002). "CUBAN GOLD GETS ROLLED IN VINELAND / STORE OFFERS CIGARS ROLLED BY CUBAN HANDS". The Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- ↑ "Identifying Counterfeit Cuban Cigars". Decaturspirits.com. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ Marvin R. Shanken, "Inside Cuban Cigars: Cigar Aficionado Interviews Cubatabaco's Top Official, Francisco Padron", Cigar Aficionado, vol. 2, no. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 75–83.

- ↑ "Che's Habanos" by Jesus Arboleya and Roberto F. Campos, Cigar Aficionado, October 1997

- ↑ "Kennedy, Cuba and Cigars". Cigar Aficionado. 1 September 1992. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ Goodwin R (5 July 2000). "President Kennedy's plan for peace with Cuba". New York Times. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ↑ "Florida Cigars: Artistry, Labor, and Politics in Florida's Oldest Industry" – Archives of the State of Florida Archived 31 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Tad Gage (1997). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Cigars. Alpha Books. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-02-861975-0. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ↑ Economist Intelligence Unit (Great Britain) (1998). Country report: Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Puerto Rico. The Unit. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ↑ Bret Saxon; Steve Stein (1 March 1998). The Art of the Shmooze. SP Books. pp. 224–30. ISBN 978-1-56171-976-1. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ↑ Gould LE (30 May 2007). "Las Vegas cigar lounges roll out the welcome mat". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ↑ Steve Saka (22 February 2002). "The Ultimate Counterfeit Cuban Cigar Primer". Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ↑ Karen Slama (1995). Tobacco and health. Springer Science & Business. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-306-45111-9. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ↑ US-Cuba travel and trade: New rules start on Friday, BBC News, 15 January 2015

- ↑ Bhattarai, Abha. "You’ll soon be able to bring back more cigars and rum from Cuba". washingtonpost.com. Washington Post. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ Wenger L, Malone R, Bero L (2001). "The cigar revival and the popular press: a content analysis, 1987–1997". Am J Public Health. 91 (2): 288–91. PMC 1446522

. PMID 11211641. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.2.288.

. PMID 11211641. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.2.288. - ↑ "Cigar Smoker of the Year Award Nominees 2013". C.Gars Ltd. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ http://www.wharf.co.uk/news/local-news/kelsey-grammer-named-cigar-smoker-12316246

Further reading

- Edith Abbott, "Employment of Women in Industries: Cigar-Making: Its History and Present Tendencies," Journal of Political Economy, vol. 15, no. 1 (January 1907), pp. 1–25. In JSTOR

- Patricia A. Cooper, Once a Cigar Maker: Men, Women, and Work Culture in American Cigar Factories, 1900–1919. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cigar |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |