Robert M. La Follette Sr.

| Robert M. La Follette Sr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Wisconsin | |

|

In office January 4, 1906 – June 18, 1925 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph V. Quarles |

| Succeeded by | Robert M. La Follette Jr. |

| 20th Governor of Wisconsin | |

|

In office January 7, 1901 – January 1, 1906 | |

| Lieutenant |

Jesse Stone James O. Davidson |

| Preceded by | Edward Scofield |

| Succeeded by | James O. Davidson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Wisconsin's 3rd district | |

|

In office March 4, 1885 – March 3, 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Burr W. Jones |

| Succeeded by | Allen R. Bushnell |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Robert Marion La Follette June 14, 1855 Primrose, Wisconsin |

| Died |

June 18, 1925 (aged 70) Washington, D.C. |

| Political party |

Republican Progressive |

| Spouse(s) | Belle Case La Follette |

| Children | Robert M. La Follette Jr., Philip La Follette, Fola La Follette, Mary La Follette |

| Alma mater | University of Wisconsin–Madison |

| Signature |

|

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob"[1] La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855 – June 18, 1925) was an American Republican (and later a Progressive) politician. He served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, was the Governor of Wisconsin, and was a U.S. Senator from Wisconsin from 1906 to 1925. He ran for President of the United States as the nominee of his own Progressive Party in 1924, carrying Wisconsin and winning 17% of the national popular vote.

His wife Belle Case La Follette, and his sons Robert M. La Follette Jr. and Philip La Follette led his political faction in Wisconsin into the 1940s. La Follette has been called "arguably the most important and recognized leader of the opposition to the growing dominance of corporations over the Government"[2] and is one of the key figures pointed to in Wisconsin's long history of political liberalism.

He is best remembered as a proponent of progressivism and a vocal opponent of railroad trusts, bossism, World War I, and the League of Nations. In 1957, a Senate Committee selected La Follette as one of the five greatest U.S. Senators, along with Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, and Robert A. Taft. A 1982 survey asking historians to rank the "ten greatest Senators in the nation's history" based on "accomplishments in office" and "long range impact on American history," placed La Follette first, tied with Henry Clay.[3] Robert La Follette is one of nine outstanding senators memorialized by portraits in the Senate reception room in US Capitol.[4] The Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs at the University of Wisconsin is named for him.[5]

Early life

La Follette was born in a log cabin in the Town of Primrose, Wisconsin,[6] just outside New Glarus, to Josiah La Follette and Mary Ferguson (widow of Alexander Buchanan). His paternal great-grandfather, Joseph La Follette, was born in France, emigrated to New Jersey, fought in the American Revolutionary War, led his family through the Cumberland Gap to Kentucky, and crossed the Ohio River into Indiana with his son, Jesse LaFollette.[7] Joseph married Phoebe Gobel, whose family came to the Massachusetts Colony from England in the 1630s.[8] Jesse's sons, Josiah and Harvey La Follette, moved to Primrose, where they established farms and participated in local government.[9]

La Follette grew up in the village of Argyle, Wisconsin. The death of his father in 1856 and the subsequent bad relationship with his stepfather made it a difficult childhood.[2] Following the death of his stepfather, his mother sold the family farm and moved to nearby Madison. He began teaching school for tuition money for the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he was "a very mediocre student who enjoyed social activities."[2]

At the school, he was deeply influenced by University president John Bascom on issues of morality, ethics and social justice.[2] La Follette studied oratory and, during his senior year, won a major Midwestern oratorical competition.[2] He graduated in 1879.

La Follette met Belle Case while attending the University of Wisconsin, and they married on December 31, 1881, at her family home in Baraboo, Wisconsin. She became a leader in the feminist movement, an advocate of women's suffrage and an important influence on the development of La Follette's ideas.[2] La Follette attended law school briefly and passed the bar in 1880.[2]

La Follette became a vegetarian for health concerns and found his diet gave him more energy and a clear head.[10]

Political career

Soon after obtaining his law license, he won the Republican nomination to the general election for Dane County District Attorney and went on to win the seat in 1880. After two terms, he went on to be elected to the United States House of Representatives, where he served for three terms. There he was noted for championing Native and African-American rights.[2] His opposition to patronage and his support for a protective tariff helped secure his appointment to the Ways and Means Committee headed by William McKinley, where he helped draft the Tariff Act of 1890 (McKinley Tariff).

At 35 years old, Robert La Follette lost his seat in the 1890 Democratic landslide. Many factors contributed to his loss, one of which included the Bennett compulsory-education bill passed by the Republican-controlled state legislature in 1889. Because the bill required major subjects in schools to be taught in English, it formed a large divide in Wisconsin both racially and ethnically within the foreign Catholic and Lutheran communities. Furthermore, the McKinley Tariff La Follette had previously supported affected the Republican demise in Congress as well. Despite the unpopularity of his views at the time, however, Congressman La Follette successfully championed the rights of minorities against prejudice.[11]

After his defeat for a fourth term in the House, La Follette returned to Madison to begin a private law practice and spend more time with his wife and four children.[2] In the early 1890s, he began to believe that much of the Republican Party had abandoned the ideals of its antislavery origins and become a tool for corporate interests. In his home state, he was convinced industry and railroad interests had too much sway over the party.[2] To counter this, La Follette began building an independent organization within the party that stressed voter control.[2]

In 1891, Senator Philetus Sawyer allegedly offered La Follette a bribe to side with him in a court case against former state officials. La Follette was so outraged by Sawyer's proposal that he spent the rest of his long career fighting corruption in government wherever he found it. His first target was his own Republican party. “Nothing else ever came into my life that exerted such a powerful influence upon me as that affair. It was the turning point, in a way, of my career. Sooner or later I probably would have done what I did in Wisconsin. But it would have been later. It would have been a matter of much slower evolution. But it shocked me into a complete realization of the extremes to which this power that Sawyer represented would go to secure the results it was after.”[12]

La Follette spent the next six years creating a Republican bloc known as "The Insurgents" "in support of other party members (Scandinavians, dairy farmers, young men, disgruntled politicians) with grievances against the stalwart faction.”[13]

The Insurgents stressed the need for more direct voting and championed consumer rights. The Insurgents' calls for reform gained more support after the Panic of 1893 shook up the economic, class, and ethnic assumptions held by most Americans.

In 1894, the Insurgents began to openly challenge the Stalwarts for leadership of the Republican Party. Their Nils Haugen sought his party's nomination for governor in 1894, and La Follette followed in 1896 and 1898. His speeches decrying the sway of big business (especially the railroads) and his call for a more direct democracy (including direct election of nominees in party primaries) drew ever larger crowds.

In 1900, La Follette formed a coalition that temporarily disrupted the Stalwart hold on the nomination process. After securing the nomination, he "traveled to sixty-one counties, gave 216 speeches and spoke to 200,000 people."[2] He gave many of his campaign speeches (which often lasted over three hours) from the back of a buckboard wagon.[2] He won the 1900 race for governor by 100,000 votes[2] and won re-election in 1904.

Governor of Wisconsin

From 1901 until 1906, La Follette served as Governor of Wisconsin — the first native-born governor of the state. During his first term, he proposed to set up a railroad commission, imposed an ad valorem tax on the railroad companies, and established a direct primary system. The Stalwarts blocked his agenda, and he refused to compromise with them.

During this time he also completed and published the ten-volume The Making of America.

During the 1904 elections, the Stalwarts organized to oppose La Follette's nomination and moved to block any reform legislation. La Follette began working to unite insurgent Democrats to form a broad coalition. He did manage to secure the passage of the primary bill and some revision to the railroad tax structure.[2]

When the legislative session concluded, La Follette traveled throughout Wisconsin reading the "roll call"; that is, he read the votes of Stalwart Republicans to the people in an effort to elect Progressives. During this campaign, La Follette gained national attention when muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens began to cover his campaign.

With the press coverage and his successful re-election, La Follette rose to become a national figure. His message against "vast corporate combinations"[2] attracted more journalists and more progressives.

As governor, La Follette championed numerous progressive reforms, including the first workers' compensation system, railroad rate reform, direct legislation, municipal home rule, open government, the minimum wage, non-partisan elections, the open primary system, direct election of U.S. Senators, women's suffrage, and progressive taxation. He created an atmosphere of close collaboration between the state government and the University of Wisconsin in the development of progressive policy, which became known as the Wisconsin Idea. The goals of his policy included the recall, referendum, direct primary, and initiative. All of these were aimed at giving citizens a more direct role in government.

The Wisconsin Idea promoted the idea of grounding legislation on thorough research and expert involvement. To implement this program, La Follette began working with University of Wisconsin–Madison faculty. This made Wisconsin a "laboratory for democracy" and "the most important state for the development of progressive legislation".[2] As governor, La Follette signed legislation that created the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Library (now Bureau) to ensure that a research agency would be available for the development of legislation.

Self-nomination for the U.S. Senate

The first item on the agenda for Wisconsin's 1905 legislature was to elect a Senator. La Follette nominated himself and was confirmed by the State Senate. He kept serving as Governor and left Wisconsin's U.S. Senate seat unfilled until January 1, 1906, when he resigned to join the U.S. Senate. He publicly proclaimed this unusual action was done to ensure that his 1904 platform was enacted in Wisconsin.[2]

Senator

La Follette spent the remainder of his life, from January 4, 1906, until his death in 1925, serving in the US Senate. While in the Senate, he strongly opposed American involvement in World War I and campaigned for child labor laws, social security, women's suffrage, and other progressive reforms. He opposed the prosecution of Eugene V. Debs and other opponents of the war and played a key role in initiating the investigation of the Teapot Dome Scandal during the Harding Administration.

A brilliant orator given to periodic bouts of "nerves," La Follette made many enemies over the years, particularly for his opposition to American entry into World War I and his defense of freedom of speech during wartime. Teddy Roosevelt called him a "skunk who ought to be hanged" when he opposed the arming of American merchant ships.[14] Mississippi Senator John Sharp Williams said he was "a better German than the head of the German parliament" when he opposed the Wilson Administration's request for a declaration of war in 1917.[15]

In 1906, when La Follette went back to Washington, D.C., the American economy had changed due to an increasing number of mergers that consolidated financial power in fewer hands. Senators Nelson Aldrich and John C. Spooner were widely seen as representing the interests of these fiscal elite. Journalist David Graham Phillips wrote a series of articles decrying corruption and subservience to corporate interests within the body entitled Treason of the Senate.[2]

As the conservative leader, Aldrich was able to limit the effectiveness of La Follette and his insurgents by placing them on insignificant committees. In response, La Follette took every chance to demand consumers' rights. When Congress adjourned, he went on a national speaking tour where he "read the roll" to expose senators he felt had voted against consumers. The tour added much to his national following.[2]

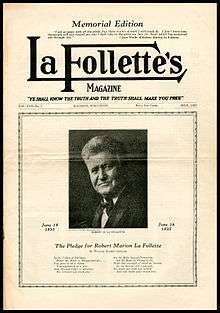

Returning to the capital, he was viewed as the leader of the Progressives. He joined with Jonathan Dolliver, Albert Cummins, and others to form a fairly formal group. They were often joined by muckraking journalists such as Steffens, Phillips, and Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis to discuss issues and strategies to limit conservative power in the legislature and the judiciary. To expand this forum, he began publishing La Follette's Weekly Magazine in 1909.[2]

La Follette believed his fears about the American economy were confirmed during the Bankers' Panic of 1907. La Follette opposed Aldrich's proposal (which had been created with the aid of financiers such as Paul Warburg). He saw the plan to issue $500 million in emergency currency backed in part by railroad bonds as an effort to establish economic centralization and crush free institutions. La Follette's troubles in the Senate worsened when fellow Progressive Theodore Roosevelt did not seek another term and William Howard Taft became President in 1909.[2]

1912 Presidential campaign and aftermath

In 1911, La Follette declared his intention to run for president and campaigned to mobilize the progressive elements in the Republican Party behind his bid. Mentally and physically exhausted, anxious over an impending operation on his thirteen-year-old daughter for tuberculosis, La Follette made a rambling speech in February 1912 before a gathering of leading magazine editors that caused many to doubt his sanity.[16] Many of his supporters deserted him for Theodore Roosevelt, who had decided to run for President again.[17] At the highly charged Republican Convention, La Follette received only 41 delegates' votes to eventual nominee William Howard Taft's 561.

An embittered, La Follette opposed both Theodore Roosevelt and Taft in the 1912 election. When his former ally, Governor Francis E. McGovern, declared his support for Roosevelt, La Follette broke with him, allowing the conservative Republicans under Emanuel Philipp to take control of Wisconsin in the 1914 election. From 1913 to 1921, La Follette and the Progressives were out of power.[18]

Opposition to American involvement in World War I

In 1909 La Follette founded La Follette's Weekly (later La Follette's Magazine) — a publication that continues in the 21st century as The Progressive.

Perhaps the most controversial of Senator La Follette's positions were his opposition to American entry into World War I and, later, his critique of the wartime policies of President Woodrow Wilson. "More than any of the other objectors to war," writes historian Thomas Ryley, "he remained a symbol of opposition to the conflict and to Wilsonian policies for prosecuting it." La Follette had cautiously supported most of Wilson's domestic program, but by 1916 he was becoming increasingly critical of the president's foreign policy.

La Follette believed the reputation of America would suffer: "When we cooperate with those governments, we endorse their methods; we endorse the violations of international law by Great Britain; we endorse the shameful methods of warfare against which we have again and again protested in this war."[19]

In many people's eyes during 1917 and 1918, La Follette was a traitor to his country, hated for insisting that America had been tricked into the conflict.[20]:1

He had been against it from the beginning. He led the filibuster of the Armed Ship Bill, for example, that would have authorized the President to arm vessels. Its main supporter, he said, was a subsidiary of the International Mercantile Marine Company, which had been formed in England. In his eyes this bill would have had American gunners answering to English ship owners "who take their orders from the British Admiralty. Hence we, professing to be a neutral nation, are placing American guns and American gunners practically under the orders of the British Admiralty."

La Follette's opposition to the measure caused President Wilson to name him as part of "A little group of willful men, representing no opinion but their own...." Most media outlets condemned La Follette in editorials and political cartoons (some of which mockingly portrayed him as receiving the Iron Cross).[20]

La Follette's staunch position against joining the war caused Senator John Sharp Williams to label him "pro-German, pretty near pro-Goth, and pro-Vandal." He was denounced in press editorials and political cartoons. After America joined the war, La Follette was a leader of the opposition to military conscription, the Espionage Act, and the President's measures to finance the war.

On August 11, 1917, he introduced a War Aims Resolution that called on the US to "declare definitely its strategic goals, to condemn the continuation of the war for the purposes of territorial annexation, and to demand that the Allies restate their peace terms immediately." This position was attacked by both the press and public officials.

On September 20, 1917, he addressed the Non-Partisan League convention in Saint Paul, Minnesota, to discuss war taxation. Responding to an audience question, he said that while America had "suffered grievance... at the hands of Germany," they were not sufficient to provoke war. "I say this, that the comparatively small privilege--the right of an American citizen to ride on a munitions loaded ship flying a foreign flag--is too small to involve this government in the loss of millions and millions of lives!!" He insisted that the President knew there was ammunition on the RMS Lusitania but had not prevented Americans from boarding it. After much audience cheering, he then defended free speech during wartime and received a standing ovation after his conclusion.[20]

Despite the existence of three stenographic reports of the address, the Associated Press misquoted La Follette claiming he had said, "we had no grievance against Germany" and that he argued the sinking of the Lusitania was justified. The AP also portrayed the meeting as disloyal. La Follette was characterized as treasonous by speakers and editors across the nation.

Historian David Thelen reports that after the St. Paul speech La Follette "became the main focus of official and vigilante campaigns to suppress antiwar spokesmen." Many organizations sent resolutions to Congress calling for his expulsion, including that of the influential Minnesota Public Safety Commission to the Senate on September 29, 1917. La Follette asked for the Senate to allow him to respond to its charges of disloyalty and sedition.

His address was scheduled for October 6, 1917. His opponents in Congress manipulated the schedule so they would follow him and prevent rebuttal. The public, sensing drama, packed the viewing galleries, and the majority of Senators made sure they were present to hear all the speeches. Upon taking the floor, La Follette read in an unemotional detached manner a speech he had prepared defending free speech in wartime. Upon his conclusion there was a spontaneous outburst of applause that had to be gavelled into order. This speech is hailed as "a classic argument for free speech during time of war".[20]

After the speech, Senators Frank B. Kellogg (Minnesota), Joseph Taylor Robinson (Arkansas), and Albert B. Fall (New Mexico) in turn attacked La Follette's position on the war. Senator Robinson was a combative and fiercely partisan defender of Wilson and the Democratic Party. His speech "synthesized the scattered attacks on La Follette that had been filtering in for seven months.... As the speech progressed, [Robinson] became more agitated and abusive; the virulence of his attack shocked the floor and galleries into complete silence."

A United Press correspondent described Robinson's speech as "the most unrestrained language that ever has been heard in the Senate." La Follette sat motionless in his chair, even when Robinson began shaking his fist at him. Near the conclusion of his speech, Robinson violated the custom of the Senate and addressed his colleague directly, pointing at La Follette and shouting, "I want to know where you stand." La Follette was not allowed to take the floor to refute the other Senators before adjournment, though Senator Fall allowed him a brief statement, whereupon he announced he was prepared to substantiate everything he said in St. Paul and desired the chance to rebut the charges being made against him by his fellow senators. Throughout the remainder of his term in the Senate, his opponents used procedural maneuvers to ensure he never was allowed to address charges of disloyalty again.[20]

La Follette's opposition to US entry into World War I caused him to break with his academic friends. He built a new base of support among anti-war German-Americans.

La Follette's son, Philip La Follette, later opposed U.S. entry into World War II, but after war was declared served as an Army officer.

1924 presidential campaign

In 1924, the Federated Farmer-Labor Party (FF-LP) sought to nominate La Follette for president, thereby uniting all progressive parties into a single national Labor Party. However, after a bitterly-fought convention in 1923, the Communist-controlled Workers Party gained control of the national organization's structure. Just prior to its 1924 convention in St. Paul, La Follette denounced the Communists and refused to be considered for the FF-LP endorsement. With La Follette's snub, the FF-LP disintegrated, leaving only the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party.

Instead, La Follette formed an independent Progressive Party and accepted its nomination in Cleveland with Democratic Senator Burton K. Wheeler of Montana as his running mate. The American Federation of Labor, the Socialist Party of America, the Conference for Progressive Political Action, most of the former FF-LP members, various former "Bull Moose" Progressives, and Midwestern Progressive movement activists then joined La Follette and supported the Progressive Party.

La Follette's platform called for government ownership of the railroads and electric utilities, cheap credit for farmers, the outlawing of child labor, stronger laws to help labor unions, more protection of civil liberties, an end to American imperialism in Latin America, and a referendum before any president could again lead the nation into war.

He came in third behind incumbent Calvin Coolidge and Democratic candidate John W. Davis. La Follette won 17% of the popular vote, carried Wisconsin (winning its 13 electoral votes) and polled second in 11 Western states. His base consisted of German-Americans, railroad workers, the AFL labor unions, the Non-Partisan League, the Socialist Party, Western farmers, and many of the "Bull Moose" Progressives who had supported Roosevelt in 1912. La Follette's 17% showing represents the third highest showing for a third party since the American Civil War (only surpassed by Roosevelt's 27% in 1912 and Ross Perot's 19% in 1992, although unlike Roosevelt and La Follette, Perot did not carry any states), while his winning of his home state represents the most recent occasion any third party presidential candidate has carried a non-Southern state.

During the 1924 convention, La Follette was filmed by Lee DeForest in DeForest's Phonofilm sound-on-film process, along with Franklin D. Roosevelt, John W. Davis, and Al Smith. Following the 1924 election, the Progressive Party disbanded.

Death and legacy

La Follette died in Washington, D.C., on June 18, 1925 of cardiovascular disease several months after the election.[21] He was buried in the Forest Hill Cemetery on the near west side of Madison.

After his death, his wife, Belle Case La Follette, remained an influential figure and editor, watching their sons Philip and Robert enter politics. By the mid-1930s, the La Follettes had reformed the Progressive Party on the state level in the form of the Wisconsin Progressive Party. The party quickly, if briefly, became the dominant political power in the state, electing seven Progressive congressmen in 1934 and 1936. Their older son, Philip La Follette, was elected Governor of Wisconsin; their younger son, Robert M. La Follette Jr., succeeded his father as Senator, leading a caucus of Progressives composed of Progressive, Farmer-Labor, American Labor, and various Republican and Democratic Party congressional representatives.

La Follette Jr. returned to the Republican Party in 1946 to run as its nominee for the Senate, but he was defeated in the primary by Joe McCarthy. His grandson, Bronson La Follette, served as Wisconsin's attorney general in the 1980s.

La Follette's daughter, Fola, was a prominent suffragette and labor activist and was married to the playwright George Middleton. His sister Josephine married Robert G. Siebecker, Chief Justice of the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

Memorials

- La Follette's cousin Chester La Follette painted the oval portrait that hangs in the Senate.

- La Follette is represented by one of two statues from Wisconsin in National Statuary Hall, also known as the Old House Chamber in the United States Capitol.

- The University of Wisconsin-Madison is home to the Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs (formerly the Robert M. La Follette Institute of Public Affairs).

- The University of Wisconsin-Madison has dedicated a segment of an undergraduate residence hall, Adams Hall in the Lakeshore area, as La Follette House.

- The Robert M. La Follette House, in Maple Bluff, Wisconsin, is a National Historic Landmark.

- La Follette High School in Madison, Wisconsin.

- A bust of La Follette resides in the rotunda of the Wisconsin state capitol.

Bibliography

Biographical

- Brøndal, Jørn, "The Ethnic and Racial Side of Robert M. La Follette," Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, (2011) 10(3): 340-353

- Burgchardt, Carl R., Robert M. La Follette, Sr.: The Voice of Conscience Greenwood Press. 1992; on his oratory, with selected speeches.

- Drake, Richard. The Education of an Anti-Imperialist Robert La Follette and U.S. Expansion (University of Wisconsin Press; 2013) 533 pages; celebration of his antiwar & anti-imperialist positions excerpt and text search

- Garraty, John A., "Robert La Follette: The Promise Unfulfilled" American Heritage (1962) 13(3): 76–79, 84–88. ISSN 0002-8738 article.

- Hale, William Bayard (June 1911). "La Follette, Pioneer Progressive: The Story of "Fighting Bob", The New Master Of The Senate And Candidate For The Presidency". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXII: 14591–14600. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- La Follette, Belle C. and Fola La Follette. Robert M. La Follette 2 vols., (1953), detailed biography by his wife and his daughter

- Scroop, Daniel. "A Life in Progress: Motion and Emotion in the Autobiography of Robert M. La Follette," American Nineteenth Century History (March 2012) 13#1 pp 45–64.

- Thelen, David, Robert M. La Follette and the Insurgent Spirit. (1976). short interpretive biography.

- Thelen, David Paul, The Early Life of Robert M. La Follette, 1855–1884. (1966).

- Unger, Nancy C. Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer (2000), full-scale biography.

Specialty studies

- Brøndal, Jørn, Ethnic Leadership and Midwestern Politics: Scandinavian Americans and the Progressive Movement in Wisconsin, 1890–1914. (2004), on his ties with Scandinavian-American leaders.

- Buenker, John D., The History of Wisconsin. Volume IV The Progressive Era, 1893–1914 (1998), detailed narrative and analysis.

- Margulies, Herbert F., The Decline of the Progressive Movement in Wisconsin, 1890–1920 (1968), detailed narrative.

- Maxwell, Robert S. La Follette and the Rise of the Progressives in Wisconsin. Madison, Wis.: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1956.

- Miller, Karen A. J., Populist Nationalism: Republican Insurgency and American Foreign Policy Making, 1918–1925 Greenwood Press, 1999.

Primary sources

See also

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–49)

- List of United States Senators expelled or censured

- Seamen's Act

Footnotes

- ↑ "La Follette Back As "Fighting Bob"". Boston Daily Globe. June 1, 1924.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Mari Jo (1994). The American Radical. New York, NY: Routledge.

- ↑ David L. Porter, "America's Ten Greatest Senators." The Rating Game in American Politics: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York: Irvington, 1987.

- ↑ "The "Famous Five" Now the "Famous Nine"". United States Senate. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ↑ The Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs at the University of Wisconsin

- ↑ Barton, A.O. (1922). La Follette's Winning of Wisconsin (1894-1904). Homestead Company. p. 226. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Joseph Lafollett / Lafollette". graves.inssar.org. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ↑ "The Goble Genealogy Homepage sponsored by the Goble Family Association". homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ↑ "LAFOLLETTE, Harvey Marion". homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Notable Vegetarians". The Literary Digest. May 24, 1913. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ↑ Unger, Nancy C. "Congressman La Follette: So Good a Fellow Even His Enemies Like Him." Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina, 2000. Pp. 95-97. Print.}

- ↑ "The Career of Robert M. La Follette." Turning Points in Wisconsin History. Wisconsin Historical Society, n.d. Web. November 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Eastland Memorial Society." Eastland Memorial Society. State Historical Society of Wisconsin Visual Archives, n.d. Web. November 13, 2014.

- ↑ Unger, Nancy. Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer, pg. 247

- ↑ Unger, pg. 249.

- ↑ "Introducing Our 1912 Project; Something's Wrong with La Follette - The Wire". theatlanticwire.com. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ↑ Goodwin, Doris Kearns. The Bully Pulpit. p. 676

- ↑ Margulies (1968) ch 3–5.

- ↑ "Opposition to Wilson's War Message". <http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/doc19.htm>.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Halford Ross Ryan (1988). Oratorical Encounters: Selected Studies and Sources of Twentieth Century Political Accusations. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Inc.

- ↑ "La Follette Dies In Capital Home. Lauded By His Foes. Final Attack of Heart Disease in Early Morning Is Fatal to Insurgent Leader". New York Times. June 19, 1925. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

Senator Robert Marion La Follette, leader of the Republican Progressives and an independent candidate for the Presidency last year, died in his home here at 1:21 P.M. today from heart disease, which had been complicated by attacks of bronchial asthma and pneumonia. ...

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert M. La Follette Sr. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert M. La Follette, Sr.. |

- Works by or about Robert M. La Follette Sr. in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

Statements

- Free Speech and the Right of Congress to Declare the Objects of the War

- Statement of Robert La Follette Sr. on Communist Participation in the Progressive Movement, 26 May 1924

Biographies

- Biography by John Nichols, at http://www.fightingbob.com

- United States Congress. "Robert M. La Follette Sr. (id: L000004)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Biography at Spartacus Educational

- Wisconsin Electronic Reader– Senator La Follette's picture biography

-

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "La Follette, Robert Marion". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

- "La Follette, Robert Marion". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- "La Follette, Robert Marion". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "La Follette, Robert Marion". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

Commemorative Government Initiatives on his Behalf

- Pub.L. 109–15, An Act to designate the facility of the United States Postal Service located at 215 Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in Madison, Wisconsin, as the "Robert M. La Follette, Sr. Post Office Building"

- Pub.L. 109–110, Honoring the life of Robert M. La Follette, Sr., on the sesquicentennial of his birth

- S. 1174, A bill to authorize the President to posthumously award a gold medal on behalf of Congress to Robert M. La Follette, Sr., in recognition of his important contributions to the Progressive movement, the State of Wisconsin, and the United States

- S. 1175, Robert M. La Follette, Sr. Commemorative Coin Act

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by None |

Progressive Party nominee for President of the United States 1924 |

Succeeded by None |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Edward Scofield |

Governor of Wisconsin 1901–1906 |

Succeeded by James O. Davidson |

| U.S. Senate | ||

| Preceded by Joseph V. Quarles |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Wisconsin 1906–1925 Served alongside: John Coit Spooner (R), Isaac Stephenson (R), Paul O. Husting (D), Irvine Lenroot (R) |

Succeeded by Robert M. La Follette Jr. |

| U.S. House of Representatives | ||

| Preceded by Burr W. Jones |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Wisconsin's 3rd congressional district 1885-1891 |

Succeeded by Allen R. Bushnell |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by Hugh S. Gibson |

Cover of Time Magazine December 3, 1923 |

Succeeded by Albert Baird Cummins |