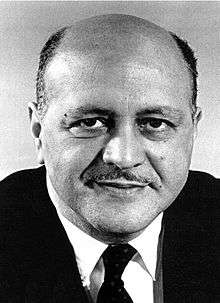

Robert C. Weaver

| Robert Weaver | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development | |

|

In office January 18, 1966 – December 18, 1968 | |

| President | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Himself (HHFA Administrator) |

| Succeeded by | Robert Wood |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Robert Clifton Weaver December 29, 1907 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died |

July 17, 1997 (aged 89) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Ella Haith |

| Education | Harvard University (BS, MA, PhD) |

Robert Clifton Weaver (December 29, 1907 – July 17, 1997) was an economist, academic, and political administrator; he served as the first United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (H.U.D.) from 1966 to 1968, in the new agency established in 1965 under President Lyndon B. Johnson. Weaver was the first African American to be appointed to a US cabinet-level position.

Prior to his appointment as cabinet officer, Weaver had served in the administration of President John F. Kennedy. In addition, he had served in New York State government, and in high-level positions in New York City. During the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, he was one of 45 prominent African Americans appointed to positions and helped make up the Black Cabinet, an informal group of African-American public policy advisers. Weaver directed federal programs during the administration of the New Deal, at the same time completing his doctorate in economics in 1934 at Harvard University.

Early life and education

Weaver was born on December 29, 1907 into a middle-class family in Washington, D.C. His parents were Morgan Weaver, a postal worker, and Margaret Freeman, of mixed-race ancestry; they encouraged the boy in his academic studies. His maternal grandfather was Dr. Robert Tanner Freeman, the first African American to graduate from Harvard in dentistry.[1]

The young Weaver attended the M Street High School, now known as the Dunbar High School. The academic high school for blacks at a time of racial segregation had a national reputation for excellence. Weaver went on to Harvard University, where he earned a Bachelor of Science and Master of Arts degree. He also earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree in economics, completing his doctorate in 1934.[1]

Marriage and family

Weaver married Ella V. Haith in 1935. They adopted a son, who died in 1962.

Career

In 1933, Weaver was appointed as an aide to United States Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes.[2] With a reputation for knowledge about housing issues, in 1934 the young Weaver was invited to join President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Black Cabinet.[3] Roosevelt appointed a total of 45 prominent blacks to positions in executive agencies, and called on them as informal advisers on public policy issues related to African Americans, the Great Depression and the New Deal.

Weaver had numerous public policy positions, in between stints in academia. He was appointed New York State Rent Commissioner (1955–1959) under Governor W. Averell Harriman, becoming the first black State Cabinet member in New York. Next, he served as the vice chairman of the New York City Housing and Redevelopment Board in 1960. Weaver contributed the compilation housing bill in 1961. He took part in lobbying for the Senior Citizens Housing Act of 1962.[4] Next, he was recruited by newly elected President John F. Kennedy to serve in his administration.[3]

Cabinet nomination

After election, Kennedy tried to establish a new cabinet department to deal with urban issues. It was to be called the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Postwar suburban development, following the construction of highways, and economic restructuring had drawn population and jobs from the cities. The nation was faced with a stock of substandard, aged housing in many cities, and problems of unemployment.

In 1961, while trying to create HUD, Kennedy had done everything short of promising the new position to Weaver. He appointed him Administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency (HHFA),[3] a group of agencies which Kennedy wanted to raise to cabinet status.

"When Dr. Weaver joined the Kennedy Administration, whose Harvard connections extended to the occupant of the Oval Office, he held more Harvard degrees – three, including a doctorate in economics – than anyone else in the administration's upper ranks."[1]

Some Republicans and southern Democrats opposed the legislation to create the new department. The following year, Kennedy unsuccessfully tried to use his reorganization authority to create the department. As a result, Congress passed legislation prohibiting presidents from using that authority to create a new cabinet department, although the previous Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower administration had created the cabinet-level U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare under that authority.

When the department was finally approved by Congress in 1965, after Kennedy's assassination two years before, many people thought that Weaver would be the best nominee. He had previously served in various posts in government with the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, as one of his unofficial Black Cabinet members.[3] In 1965, he was still Administrator of the HHFA. In public, President Lyndon B. Johnson reiterated Weaver's status as a potential nominee but would not promise him the position. In private, Johnson had strong reservations. He often held pro-and-con discussions with Roy Wilkins, Executive Director of the NAACP.

Johnson wanted a strong proponent for the new department. Johnson worried about Weaver's political sense. Johnson seriously considered other candidates, none of whom was black. He wanted a top administrator, but also someone who was exciting. Johnson was worried about how the new Secretary would interact with congressional representatives from the Solid South; they were overwhelmingly Democrat as most African Americans were still disenfranchised and excluded from the political system. This was expected to change as the federal government enforced civil rights and the provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. As candidates, Johnson considered the politician Richard Daley, mayor of Chicago; and the philanthropist Laurence Rockefeller.

Ultimately, Johnson believed that Weaver was the best-qualified administrator. His assistant Bill Moyers had rated Weaver highly on potential effectiveness as the new Secretary. Moyers noted Weaver's strong accomplishments and ability to create teams. Ten days after receiving the report, the president put forward the nomination, and Weaver was successfully confirmed by the United States Senate.

Concern about housing issues

Weaver had expressed his concerns about African Americans’ housing issue before 1930 in his article, “Negroes Need Housing”, published by the magazine The Crisis of the NAACP after the Stock Market Crash.[5] He noted there was a great difference between the income of most African Americans and the cost of living; African Americans did not have enough housing supply because of many social factors, including the long economic decline of rural areas in the South. He suggested a government housing program to enable all the African Americans the chance to buy or rent their house.

Weaver drafted the U.S Housing Program under Roosevelt, which was established in 1937. The program was intended to provide financial support to local housing departments, as a subsidy toward lowering the rent poor African Americans had to pay. The program decreased the average rent from $19.47 per month to $16.80 per month.

Weaver claimed the scope of this program was insufficient, as there were still many African Americans who made less than the average income. They could not afford to pay for both food and housing. In addition, generally restricted to segregated housing, African Americans could not necessarily take advantage of other subsidized housing.

Secretary of HUD

In 1966 Weaver became the first African-American to become a cabinet member. Weaver was head of Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

Later years

After serving under Johnson, Weaver became president of Baruch College in 1969. The following year, he became a professor of Urban Affairs at Hunter College in New York. He taught there until 1978.

Weaver died in Manhattan, New York on July 17, 1997, at the age of 89.[1]

Legacy and honors

- 1962, the Spingarn Medal by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

- 2000, the HUD headquarters building, which Weaver had dedicated at its completion in 1968, was renamed the Robert C. Weaver Federal Building in his honor

- 2006, a street is named after him in NE Washington D.C., "Robert Clifton Weaver Way"

Books

Weaver wrote a number of books regarding black issues and urban housing, including:

- Negro Labor: A National Problem (1946)

- The Negro Ghetto (1948)

- The Urban Complex: Human Values in Urban Life (1964)

- Dilemmas of Urban America (1965)

Further reading

- Pritchett, Wendell E. (October 1, 2008). Robert Clifton Weaver and the American City: The Life and Times of an Urban Reformer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-226-68448-2.

Primary sources

- "Weaver, Robert Clifton." Infoplease

- Speech by Robert Weaver given on April 8, 1969. Audio recording from The University of Alabama's Emphasis Symposium on Contemporary Issues

President Johnson discussed Weaver's possible nomination as secretary of HUD with major leaders across the country:

- Telephone Conversation between President Johnson and Martin Luther King, Jr., 15 January 1965, 12:06pm, Citation # 6736, Recordings of Telephone Conversations, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Telephone Conversation between President Johnson and Richard Daley, 15 September 1965, 9:40am, Citation # 8870, Recordings of Telephone Conversations, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Telephone Conversation between President Johnson and Richard Daley, 1 December 1965, 9:56am, Citation # 9301, Recordings of Telephone Conversations, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Telephone Conversation between President Johnson and Roy Wilkins, 15 July 1965, 2:40pm, Citation # 8340, Recordings of Telephone Conversations, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Telephone Conversation between President Johnson and Roy Wilkins, 1 November 1965, 10:11am, Citation # 9101, Recordings of Telephone Conversations, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Telephone Conversation between President Johnson and Roy Wilkins, 4 November 1965, 10:50am, Citation # 9106, Recordings of Telephone Conversations, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Telephone Conversation between President Johnson and Roy Wilkins, 5 January 1966, 4:55pm, Citation # 9430, Recordings of Telephone Conversations, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Telephone Conversation between President Johnson and Thurgood Marshall, 3 January 1965, 10:15am, Citation # 9403, Recordings of Telephone Conversations, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 James Barron, "Robert C. Weaver, 89, First Black Cabinet Member, Dies" The New York Times (July 19, 1997). Retrieved April 15, 2010

- ↑ Chenrow, Fred; Chenrow, Carol (1973). Reading Exercises in Black History, Volume 1. Elizabethtown, PA: The Continental Press, Inc. p. 56. ISBN 08454-2107-7

- 1 2 3 4 "New Administration: Ornaments on the Tree" Time (January 6, 1961). Retrieved May 20, 2011

- ↑ "American President: A Reference Resource". University of Virginia Miller Center. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ The Crisis. "Negroes Need Housing". Google Books. The Crisis Publishing Company. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jack Conway Acting |

Administrator of Housing and Home Finance Agency 1961–1966 |

Succeeded by Himself as United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development |

| Preceded by Himself as Administrator of Housing and Home Finance Agency |

United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development 1966–1968 |

Succeeded by Robert Wood |