Right-hand rule

In mathematics and physics, the right-hand rule is a common mnemonic for understanding orientation conventions for vectors in three dimensions.

Most of the various left and right-hand rules arise from the fact that the three axes of 3-dimensional space have two possible orientations. This can be seen by holding your hands outward and together, palms up, with the fingers curled. If the curl of your fingers represents a movement from the first or X axis to the second or Y axis then the third or Z axis can point either along your left thumb or right thumb. Left and right-hand rules arise when dealing with co-ordinate axes, rotation, spirals, electromagnetic fields, mirror images and enantiomers in mathematics and chemistry.

Coordinates

Right-handed coordinates on the right.

| Axis or vector | Two fingers and thumb | Curled fingers |

|---|---|---|

| X, 1, or A | First or index | Fingers extended |

| Y, 2, or B | Second finger or palm | Fingers curled 90° |

| Z, 3, or C | Thumb | Thumb |

Coordinates are usually right-handed.

For right-handed coordinates your right thumb points along the Z axis in a positive Z-direction and the curl of your fingers represents a motion from the first or X axis to the second or Y axis. When viewed from the top or Z axis the system is counter-clockwise.

For left-handed coordinates your left thumb points along the Z axis in a positive Z-direction and the curled fingers of your left hand represent a motion from the first or X axis to the second or Y axis. When viewed from the top or Z axis the system is clockwise.

Interchanging the labels of any two axes reverses the handedness. Reversing the direction of one axis (or of all three axes) also reverses the handedness. (If the axes do not have a positive or negative direction then handedness has no meaning.) Reversing two axes amounts to a 180° rotation around the remaining axis.[1]

Note that the convention of assigning the index finger to the first axis (rather than the thumb) corresponds with the convention of finger-counting of the United Kingdom and United States, whereas for Continental Europeans, the thumb represents the first digit to be counted; the "natural" assignment of fingers to axes that leads to a "right"-handed rule would likewise differ in many other cultures.

Rotation

A rotating body

In mathematics a rotating body is commonly represented by a vector along the axis of rotation. The length of the vector gives the speed of rotation and the direction of the axis gives the direction of rotation according to the right-hand rule: right fingers curled in the direction of rotation and the right thumb pointing in the positive direction of the axis. This allows some easy calculations using the vector cross product. Note that no part of the body is moving in the direction of the axis arrow, which takes some getting used to. By coincidence, if your thumb points north the earth rotates according to the right-hand rule. This causes the sun and stars to appear to revolve according to the left-hand rule.

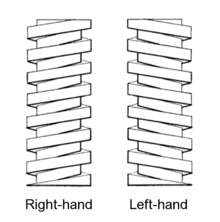

Helices and screws

For a right-handed screw the threads on the right are always slightly higher than those on the left, regardless of whether the screw is pointing up or down.

A helix, to use a more accurate term than spiral, is basically a circular curve that advances along the z-axis while rotating in the x-y plane. Helices are either right- or left-handed, curled fingers giving the direction of rotation and thumb giving the direction of advance. The two types are mirror images of each other, physically distinct and cannot be transformed into each other by any physical operation such as turning them over.

The threads on a right-handed screw are a right-handed helix. They are basically a long inclined plane wrapped around a cylinder such that turning the screw advances the screw back and forth along the z-axis. From the point of view of the external threads, turning the screw forces the screw up or down the inclined plane. If a screw is right-handed (most screws are) the rule is this: point your right thumb in the direction you want the screw to go and turn the screw in the direction of your curled right fingers.

The Coriolis effect

Viewed from the rotating earth, the path of an object moving in a straight line appears to bend to the right in the northern hemisphere and to the left in the southern hemisphere. This causes low-pressure areas in the northern hemispheres to rotate according to the right-hand rule (thumb pointing away from the earth). Handedness is not obvious here but it is clear in the underlying mathematics (vector cross product).

Electromagnetics

- When electricity flows in a long straight wire it creates a circular or cylindrical magnetic field around the wire according to the right-hand rule. The conventional current, which is the opposite of the actual flow of electrons, is a flow of positive charges along the positive Z-axis. The conventional direction of a magnetic line is given by a compass needle.

- Electromagnet: The magnetic field around a wire is quite weak. If you coil the wire into a right-handed (or left-handed) helix all the field lines inside the helix point in the same direction and each successive coil reinforces the others. The advance of the helix, the non-circular part of the current and the field lines all point in the positive Z direction. Since there is no magnetic monopole the field lines exit the +Z end, loop around outside the helix, and reenter at the -Z end. The +Z end where the lines exit is defined as the north pole. If you curl the fingers of your right hand in the direction of the circular component of the current your right thumb points to the north pole.

- Lorentz force: If a positive electric charge moves across a magnetic field it experiences a force according to the right-hand rule. If the curl of your right fingers represents a rotation from the direction the charge is moving to the direction of the magnetic field then the force is in the direction of your right thumb. Because the charge is moving, the force causes the particle path to bend. The bending force is computed by the vector cross product. This means that the bending force increases with the velocity of the particle and the strength of the magnetic field. The force is maximum when the particle direction and magnetic fields are at right angles, is less at any other angle and is zero when the particle moves parallel to the field.

Ampère's right-hand grip rule

Ampère's right-hand grip rule[2] (also called right-hand screw rule, coffee-mug rule or the corkscrew-rule) is used either when a vector (such as the Euler vector) must be defined to represent the rotation of a body, a magnetic field, or a fluid, or vice versa, when it is necessary to define a rotation vector to understand how rotation occurs. It reveals a connection between the current and the magnetic field lines in the magnetic field that the current created.

André-Marie Ampère, a French physicist and mathematician, for whom the rule was named, was inspired by Hans Christian Ørsted, another physicist who experimented with magnet needles. Ørsted observed that the needles swirled when in the proximity of an electric current-carrying wire, and concluded that electricity could create magnetic fields.

Application

This version of the rule is used in two complementary applications of Ampère's circuital law:

- An electric current passes through a solenoid, resulting in a magnetic field. When wrapping the right hand around the solenoid with the fingers in the direction of the conventional current, the thumb points in the direction of the magnetic north pole.

- An electric current passes through a straight wire. Grabbing the wire points the thumb in the direction of the conventional current (from positive to negative), while the fingers point in the direction of the magnetic flux lines. The direction of the magnetic field (counterclockwise instead of clockwise when viewed from the tip of the thumb) is a result of this convention and not an underlying physical phenomenon. The thumb points direction of current and fingers point direction of magnetic lines of force.

The rule is also used to determine the direction of the torque vector. When gripping the imaginary axis of rotation of the rotational force so that your fingers point in the direction of the force, the extended thumb points in the direction of the torque vector.

Cross products

The cross product of two vectors is often taken in physics and engineering. For example, in statics and dynamics, torque is the cross product of lever length and force, while angular momentum is the cross product of linear momentum and distance. In electricity and magnetism, the force exerted on a moving charged particle when moving in a magnetic field B is given by:

The direction of the cross product may be found by application of the right hand rule as follows:

- The index finger points in the direction of the velocity vector v.

- The middle finger points in the direction of the magnetic field vector B.

- The thumb points in the direction of the cross product F.

For example, for a positively charged particle moving to the North, in a region where the magnetic field points West, the resultant force points up.[1]

Applications

The right hand rule is in widespread use in physics. A list of physical quantities whose directions are related by the right-hand rule is given below. (Some of these are related only indirectly to cross products, and use the second form.)

- For a rotating object, if the right-hand fingers follow the curve of a point on the object, then the thumb points along the axis of rotation in the direction of the angular velocity vector.

- A torque, the force that causes it, and the position of the point of application of the force.

- A magnetic field, the position of the point where it is determined, and the electric current (or change in electric flux) that causes it.

- A magnetic field in a coil of wire and the electric current in the wire.

- The force of a magnetic field on a charged particle, the magnetic field itself, and the velocity of the object.

- The vorticity at any point in the field of flow of a fluid.

- The induced current from motion in a magnetic field (known as Fleming's right-hand rule).

- The x, y and z unit vectors in a Cartesian coordinate system can be chosen to follow the right-hand rule. Right-handed coordinate systems are often used in rigid body and kinematics.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Right-hand rule. |

- Chirality (mathematics)

- Curl (mathematics)

- Fleming's left-hand rule for motors

- Improper rotation

- ISO 2

- Oersted's law

- Pseudovector

- Reflection (mathematics)

References

- 1 2 Watson, George (1998). "PHYS345 Introduction to the Right Hand Rule". udel.edu. University of Delaware.

- ↑ IIT Foundation Series: Physics – Class 8, Pearson, 2009, p. 312.

External links

- Right and Left Hand Rules - Interactive Java Tutorial National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- A demonstration of the right-hand rule at physics.syr.edu

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Right-hand rule". MathWorld.

- Dr. Johannes Heidenhain : Right Hand Rule - Heidenhain TNC Training : heidenhain.de

- Christian Moser : right-hand-rule : wpftutorial.net