Bartonella quintana

| Bartonella quintana | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Rhizobiales |

| Family: | Bartonellaceae |

| Genus: | Bartonella |

| Species: | B. quintana |

| Binomial name | |

| Bartonella quintana (Schmincke 1917) Brenner et al. 1993 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Bartonella quintana, originally known as Rochalimaea quintana,[2] and "Rickettsia quintana",[3] is a microorganism transmitted by the human body louse.[4] This microorganism is the causative agent of trench fever.[4] This bacterium resulted in over 1 million soldiers in Europe during World War I being infected with trench fever.[5]

Genome

B. quintana has an estimated genome size of 1,700 to 2,174 kb.[6]

Background and characteristics

B. quintana is a fastidious, aerobic, Gram-negative, rod-shaped (bacillus) bacterium. The infection caused by this microorganism, trench fever, was first documented in soldiers during World War I, but has now been seen Europe, Asia, and North Africa. Its primary vector is known to be Pediculus humanus variety corporis, also known as the human body louse.[7] It was first isolated in axenic culture by J.W. Vinson in 1960, from a patient in Mexico City. He then followed Koch's postulates, infecting volunteers with the bacterium, showing consistent symptoms and clinical manifestations of trench fever. The medium best for growing this bacterium is blood-enriched in an atmosphere containing 5% carbon dioxide.[3]

Pathophysiology

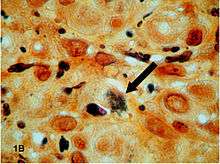

Humans are the only known animal host for this bacterium in vivo. It infects endothelial cells and can infect erythrocytes by binding and entering with a large vacuole. Once inside, they begin to proliferate and cause nuclear atypia (intraerythrocytic B.quintana colonization).[8] This leads to apoptosis being suppressed, proinflammatory cytokines are released, and vascular proliferation increases. All of these processes result in patients possessing systemic symptoms (chills, fever, diaphoresis), bacteremia, and lymphatic enlargement. A major role in B. quintana infection is its lipopolysaccharide covering which is an antagonist of the toll-like receptor 4.[9] The reason this infection might persist is because this organism also results in monocytes overproducing interleukin-10 (IL-10), thus weakening the immune response. B. quintana also induces lesions seen in bacillary angiomatosis that protrude into vascular lumina, often occluding blood flow. The enhanced growth of these cells is believed to be due to the secretion of angiogenic factors, thus inducing neovascularization. Release of an icosahedral particle, 40 nm in length, has been detected in cultures of B. quintana's close relative, B. henselae. This particle contains a 14-kb linear DNA segment, but its function in Bartonella pathophysiology is still unknown.[10] In trench fever or B. quintana-induced endocarditis patients, bacillary angiomatosis lesions are also seen. Notably, endocarditis is a new manifestation of the infection, not seen in World War I troops.

Ecology and epidemiology

B. quintana infection has subsequently been seen in every continent except Antarctica. Local infections have been associated with risk factors such as poverty, alcoholism, and homelessness. Serological evidence of B. quintana infection showed, of hospitalized homeless patients, 16% were infected, as opposed to 1.8% of nonhospitalized homeless persons, and 0% of blood donors at large.[11] Lice have been demonstrated, as of recently, to be the key component in transmitting B. quintana.[12][13] This has been attributed to living in unsanitary conditions and crowded areas, where the risk of coming into contact with other individuals carrying B. quintana and ectoparasites (body lice) is increased. Also noteworthy, the increasing migration worldwide may also play a role in spreading trench fever, from areas where it is endemic to susceptible populations in urban areas. Recent concern is the possibility of the emergence of new strains of B. quintana through horizontal gene transfer, which could result in the acquisition of other virulence factors.[7]

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of B. quintana infection are highly variable. The incubation period is now known to be 5–20 days, as opposed to original thought which was 3–38 days. The infection can start as an acute onset of a febrile episode, relapsing febrile episodes, or as a persistent typhoidal illness; commonly seen are maculopapular rashes, conjunctivitis, headache, and myalgias, with splenomegaly being less common. Most patients present with pain in the lower legs (shins), sore muscles of the legs and back, and hyperaesthesia of the shins. Rarely is B. quintana infection fatal, unless endocarditis develops and goes untreated. Weight loss, and thrombocytopenia are sometimes also seen. Recovery can take up to a month.

Diagnosis and treatment

To have a definite diagnosis of infection with B. quintana requires either serological cultures or nucleic acid amplification techniques. To differentiate between different species, immunofluorescence assays that use mouse antisera are used, as well as DNA hybridization and restriction fragment length polymorphisms, or citrate synthase gene sequencing.[14] Treatment usually consists of a 4- to 6-week course of doxycycline, erythromycin, or azithromycin.[15][16]

References

- ↑ "Bartonella quintana". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Definition of Bartonella quintana". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- 1 2 Ohl, ME; Spach, DH (2000). "Bartonella quintana and urban trench fever". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 31 (1): 131–5. PMID 10913410. doi:10.1086/313890.

- 1 2 O'Rourke, Laurie G.; Pitulle, Christian; Hegarty, Barbara C.; Kraycirik, Sharon; Killary, Karen A.; Grosenstein, Paul; Brown, James W.; Breitschwerdt, Edward B. (2005). "Bartonella quintana in Cynomolgus Monkey (Macaca fascicularis)". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (12): 1931–4. PMID 16485482. doi:10.3201/eid1112.030045.

- ↑ Jackson, Lisa A.; Spach, David H. (1996). "Emergence of Bartonella quintana Infection among Homeless Persons". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2 (2): 141–4. PMC 2639836

. PMID 8903217. doi:10.3201/eid0202.960212.

. PMID 8903217. doi:10.3201/eid0202.960212. - ↑ Roux, V; Raoult, D (1995). "Inter- and intraspecies identification of Bartonella (Rochalimaea) species". Journal of clinical microbiology. 33 (6): 1573–9. PMC 228218

. PMID 7650189.

. PMID 7650189. - 1 2 Maurin, M; Raoult, D (1996). "Bartonella (Rochalimaea) quintana infections". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 9 (3): 273–92. PMC 172893

. PMID 8809460.

. PMID 8809460. - ↑ Hadfield, T.L.; Warren, R.; Kass, M.; Brun, E.; Levy, C. (1993). "Endocarditis caused by Rochalimaea henselae". Human Pathology. 24 (10): 1140–1. PMID 8406424. doi:10.1016/0046-8177(93)90196-N.

- ↑ Popa, C.; Abdollahi-Roodsaz, S.; Joosten, L. A. B.; Takahashi, N.; Sprong, T.; Matera, G.; Liberto, M. C.; Foca, A.; et al. (2007). "Bartonella quintana Lipopolysaccharide Is a Natural Antagonist of Toll-Like Receptor 4". Infection and Immunity. 75 (10): 4831–7. PMC 2044526

. PMID 17606598. doi:10.1128/IAI.00237-07.

. PMID 17606598. doi:10.1128/IAI.00237-07. - ↑ Leboit, Philip E.; Berger, Timothy G.; Egbert, Barbara M.; Beckstead, Jay H.; Benedict Yen, T. S.; Stoler, Mark H. (1989). "Bacillary Angiomatosis: The Histopathology and Differential Diagnosis of a Pseudoneoplastic Infection in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 13 (11): 909–20. PMID 2802010. doi:10.1097/00000478-198911000-00001.

- ↑ Brouqui, P.; Houpikian, P.; Dupont, H. T.; Toubiana, P.; Obadia, Y.; Lafay, V.; Raoult, D. (1996). "Survey of the Seroprevalence of Bartonella quintana in Homeless People". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 23 (4): 756–9. PMID 8909840. doi:10.1093/clinids/23.4.756.

- ↑ Koehler, Jane E.; Sanchez, Melissa A.; Garrido, Claudia S.; Whitfeld, Margot J.; Chen, Frederick M.; Berger, Timothy G.; Rodriguez-Barradas, Maria C.; Leboit, Philip E.; Tappero, Jordan W. (1997). "Molecular Epidemiology of Bartonella Infections in Patients with Bacillary Angiomatosis–Peliosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (26): 1876–83. PMID 9407154. doi:10.1056/NEJM199712253372603.

- ↑ Brouqui, Philippe; Lascola, Bernard; Roux, Veronique; Raoult, Didier (1999). "Chronic Bartonella quintana Bacteremia in Homeless Patients". New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (3): 184–9. PMID 9895398. doi:10.1056/NEJM199901213400303.

- ↑ Cooper, M. D.; Hollingdale, M. R.; Vinson, J. W.; Costa, J. (1976). "A Passive Hemagglutination Test for Diagnosis of Trench Fever Due to Rochalimaea quintana". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 134 (6): 605–9. PMID 63526. doi:10.1093/infdis/134.6.605.

- ↑ Slater, Leonard N.; Welch, David F.; Hensel, Diane; Coody, Danese W. (1990). "A Newly Recognized Fastidious Gram-negative Pathogen as a Cause of Fever and Bacteremia". New England Journal of Medicine. 323 (23): 1587–93. PMID 2233947. doi:10.1056/NEJM199012063232303.

- ↑ Myers, WF; Grossman, DM; Wisseman Jr, CL (1984). "Antibiotic susceptibility patterns in Rochalimaea quintana, the agent of trench fever". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 25 (6): 690–3. PMC 185624

. PMID 6742814. doi:10.1128/aac.25.6.690.

. PMID 6742814. doi:10.1128/aac.25.6.690.

External links

- "Bartonella quintana". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 803.

- Type strain of Bartonella quintana at BacDive - the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase