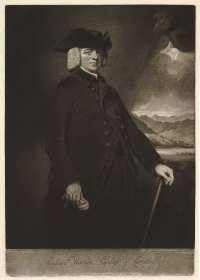

Richard Watson (bishop of Llandaff)

Richard Watson (1737–1816) was an Anglican bishop and academic, who served as the Bishop of Llandaff from 1782 to 1816. He wrote some notable political pamphlets. In theology, he belonged to an influential group of followers of Edmund Law that included also John Hey and William Paley.[1]

Life

Watson was born in Heversham, Westmorland (now Cumbria), and educated at Heversham Grammar School and Trinity College, Cambridge,[2] on a scholarship endowed by Edward Wilson of Nether Levens (1557–1653).[3] In 1759 he graduated as Second Wrangler after having challenged Massey for the position of Senior Wrangler. This challenge, in part, prompted the University Proctor, William Farish, to introduce the practice of assigning specific marks to individual questions in University tests and, in so doing, replaced the practice of 'judgement' at Cambridge with 'marking'. Marking subsequently emerged as the predominant method to determine rank order in meritocratic systems.[4] In 1760 he became a fellow of Trinity[2] and in 1762 received his MA degree. He became a professor of chemistry in 1764 and was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1769 after publishing a paper on the solution of salts in Philosophical Transactions.

Watson's theological career began when he became the Cambridge Regius Professor of Divinity in 1771.[2] In 1773, he married Dorothy Wilson, daughter of Edward Wilson of Dallam Tower and a descendant of the eponymous benefactor who had endowed Watson's scholarship. In 1774, he took up the position of prebendary of Ely Cathedral. He became archdeacon of Ely and rector of Northwold in 1779, leaving the Northwold post two years later to become rector of Knattoft. In 1782, he left all his previous appointments to take up the post of Bishop of Llandaff, which he held until his death in 1816. In 1788, he purchased the Calgarth estate in Troutbeck Bridge, Windermere, Westmorland. The same year he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[5]

Watson was buried at St Martin's Church in Windermere.

Works

Watson contributed to the Revolution controversy, with A treatise upon the authenticity of the Scriptures, and the truth of the Christian religion (1792) and most notably in 1796 when he delivered his counterblast to Thomas Paine's The Age of Reason in An Apology for the Bible which he had "reason to believe, was of singular service in stopping that torrent of irreligion which had been excited by [Paine's] writings".[6] In 1798 he published An Address to the People of Great Britain, which argued for national taxes to be raised to pay for the war against France and to reduce the national debt. Gilbert Wakefield, a Unitarian minister who taught at Warrington Academy, responded with A Reply to Some Parts of the Bishop Llandaff's Address to the People of Great Britain, attacking the privileged position of the wealthy.

An autobiography, Anecdotes of the life of Richard Watson, Bishop of Landaff, was finished in 1814 and published posthumously in 1817.

In the 19th century, it was rumoured that Watson had been the first to propose the electric telegraph, but this is incorrect. At the time William Watson (1715–1787) made researches in electricity, but even he was not involved in the telegraph.[7]

Notes

- ↑ Hans J. Hillerbrand (2 August 2004). Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set. Routledge. p. 558. ISBN 978-1-135-96028-5.

- 1 2 3 "Watson, Richard (WT754R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ R Percival Brown, Edward Wilson of Nether Levens (1557–1653) and his kin (Kendal, 1930)

- ↑ Pollitt, A. (2012). Comparative judgement for assessment. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 22(2), 157–170.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter W" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ Anecdotes of the life of Richard Watson, Bishop of Landaff (1817) p. 287.

- ↑ Bishop Watson and the Electric Telegraph, by Dr. Hamel, of St. Petersburg, in The Journal of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, vol. 9 (25 October 1861), pp. 790–791.

References

- Palmer, Bill (2007). "Richard Watson, Bishop of Llandaff (1737–1816): A chemist of the chemical revolution". Australian Journal of Education in Chemistry. Perth, Australia: Royal Australian Chemical Institute (68): 33–38.

External links

- Watson's rebuttal to the Age of Reason

- The Wisdom and Goodness of God, in Having Made Both Rich and Poor from Project Canterbury