Richard Mentor Johnson

| Richard Mentor Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 9th Vice President of the United States | |

|

In office March 4, 1837 – March 4, 1841 | |

| President | Martin Van Buren |

| Preceded by | Martin Van Buren |

| Succeeded by | John Tyler |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 13th district | |

|

In office March 4, 1833 – March 3, 1837 | |

| Preceded by | District created |

| Succeeded by | William Wright Southgate |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 5th district | |

|

In office March 4, 1829 – March 3, 1833 | |

| Preceded by | Robert L. McHatton |

| Succeeded by | Robert P. Letcher |

| United States Senator from Kentucky | |

|

In office December 10, 1819 – March 3, 1829 | |

| Preceded by | John J. Crittenden |

| Succeeded by | George M. Bibb |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 3rd district | |

|

In office March 4, 1813 – March 3, 1819 | |

| Preceded by | Stephen Ormsby |

| Succeeded by | William Brown |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 4th district | |

|

In office March 4, 1807 – March 3, 1813 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Sandford |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Desha |

| Member of the Kentucky House of Representatives | |

|

In office 1804–1806 1819 1841–1843 1850 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

October 17, 1780 Beargrass, Virginia (now Kentucky), United States |

| Died |

November 19, 1850 (aged 70) Frankfort, Kentucky |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican, Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Julia Ann Chinn (c.1790–1833) (common law marriage) |

| Relations |

Brother of James Johnson Brother of John Telemachus Johnson Uncle of Robert Ward Johnson |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater | Transylvania University |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1812–1814 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars | |

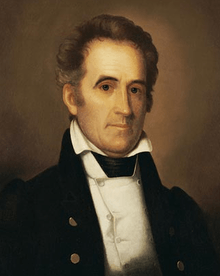

Richard Mentor Johnson (October 17, 1780[a] – November 19, 1850) was the ninth Vice President of the United States, serving in the administration of Martin Van Buren (1837–41). He is the only vice president ever elected by the United States Senate under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment. Johnson also represented Kentucky in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate; he began and ended his political career in the Kentucky House of Representatives.

Johnson was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1806. He became allied with fellow Kentuckian Henry Clay as a member of the War Hawks faction that favored war with Britain in 1812. At the outset of the War of 1812, Johnson was commissioned a colonel in the Kentucky Militia and commanded a regiment of mounted volunteers from 1812 to 1813. He and his brother James served under William Henry Harrison in Upper Canada. Johnson participated in the Battle of the Thames. Some reported that he personally killed the Shawnee chief Tecumseh, which he later used to his political advantage.

After the war, Johnson returned to the House of Representatives. The legislature appointed him to the Senate in 1819 to fill the seat vacated by John J. Crittenden. As his prominence grew, his interracial relationship with Julia Chinn, an octoroon slave, was more widely criticized. It worked against his political ambitions. Unlike other upper class leaders who had African American mistresses but never mentioned them, Johnson openly treated Chinn as his common law wife. He acknowledged their two daughters as his children, giving them his surname, much to the consternation of some of his constituents. The relationship is believed to have led to the loss of his Senate seat in 1829, but his Congressional district returned him to the House the next year.

In 1836, Johnson was the Democratic nominee for vice-president on a ticket with Martin Van Buren. Campaigning with the slogan "Rumpsey Dumpsey, Rumpsey Dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh", Johnson fell one short of the electoral votes needed to secure his election. Virginia's delegation to the Electoral College went against the state's popular vote and refused to endorse Johnson, abstaining instead.[1] However, he was elected to the office by the Senate.

Johnson proved such a liability for the Democrats in the 1836 election that they refused to renominate him for vice-president in 1840. President Van Buren campaigned for re-election without a running mate. He lost to William Henry Harrison, a Whig. Johnson tried to return to public office but was defeated. He finally was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1850, but he died on November 19, 1850, just two weeks into his term.

Early life and education

Richard Mentor Johnson was born on October 17, 1780, the fifth of Robert and Jemima (Suggett) Johnson's eleven children.[2] His father had served as a Fayette County representative in the Virginia House of Burgesses, while his mother "came from a wealthy and politically connected family."[3] At the time of Johnson's birth, fortunes of the Johnson family were tied up with indigenous peoples. Resistance by such peoples stopping the family from moving there for numerous years, and when they were able to settle there, they constructed a stockade around their house since a "multi-tribal coalition contested US claims to the region" after the Treaty of Paris in 1783.[4] At the time, the family was living in the newly founded settlement of "Beargrass", near present-day Louisville, Kentucky[5] which was part of Virginia until Kentucky was organized and admitted as a state in 1792. Two years later, the border war had ended. Soon thousands more would join the Johnsons in Kentucky, with 324,000 whites living in the state by 1800.[6]

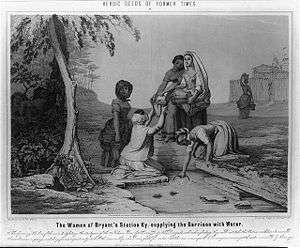

By 1782, the Johnsons had moved to Bryan's Station (future Lexington) in Fayette County.[7] Johnson's mother was considered among the heroic women of the community because of her actions during Simon Girty's raid on Bryan's Station in August 1782.[7][8] According to tradition, as Girty's forces surrounded the fort, the occupants discovered that they had almost no water inside to withstand a siege.[9] Several Indians had concealed themselves near the spring outside the fort. The Kentuckians reasoned that the Indians would stay hidden until they attacked.[9] Jemima Johnson approved a plan for the women to go alone and collect water from the spring as usual.[10] Many men disapproved of the plan, fearing the women would be attacked and killed. However, faced with no other option they finally agreed.[9] Shortly after sunrise, the women went to the spring and returned without incident.[10]

Not long after they had returned, the attack began.[10] Indian warriors set fire to several houses and stables, but a favorable wind kept the fires from spreading.[10] Children used the water drawn by the women to put out the fires.[11] A flaming arrow landed in baby Richard Johnson's crib, but it was doused by his sister Betsy.[11] Help arrived from Lexington and Boone Station, and the Indians retreated.[11]

By 1784, the Johnson family was at Great Crossing in Scott County. In 1779, Johnson purchased 2000 acres from Patrick Henry and a large portion of James Madison's 3000-acre land grant in the area.[2] As a surveyor, Robert Johnson became successful through well-chosen land purchases and being early in the region when huge land grants were made.[12]

The son Richard Johnson did not begin his formal education until age fifteen, since there were no schools on the frontier. He entered Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky.[13] While studying law (reading the law) as a legal apprentice with George Nicholas and James Brown by 1799 at the university, where his father was a trustee, he quickly drawn into politics like his father.[14] Nicholas and Brown were professors of law at the university in addition to being in private practice, with his apprenticeship the customary way for many young men to enter the law.

At least two of Johnson's brothers had notable careers as well: the eldest, James Johnson, went into shipping and stagecoach lines.[15] A younger brother, John T. Johnson, became a minister and prominent in the Christian Churches,[15] a 19th-century movement in the Protestant congregations.

Career

Johnson was admitted to the Kentucky bar in 1802, and opened his office at Great Crossing.[7] Later, he owned a retail store and pursued a number of business ventures with his brothers.[5] Johnson often worked pro bono for poor people, prosecuting their cases when they had merit.[16] He also opened his home to disabled veterans, widows, and orphans.[5]

Marriage and family

Family tradition holds that Johnson broke off an early marital engagement when he was about sixteen years old because of his mother's disapproval.[5] Purportedly Johnson vowed revenge for his mother's interference. Despite the fact that the engagement was broken off, a daughter named Celia was born. She was raised by the Johnson family and later married to Wesley Fancher, one of the men who served in Johnson's regiment at the Battle of the Thames.

After his father died, Richard Johnson inherited Julia Chinn, an octoroon slave (one-eighth African, seven-eighths European in ancestry), born into slavery around 1790 and a person who had grown up in the same household as him.[17][18] Johnson began a long-term relationship with her and treated her as his common-law wife. Chinn was simply put, the concubine of Johnson, later having the role as mother of their children and manager of plantation.[19] With this, both Chinn and Johnson championed the "notion of a diverse society" with the multiracial Chinn-Johnson family. They were prohibited from marrying because she was a slave.[20] When Johnson was away from his Kentucky plantation, he authorized Chinn to manage his business affairs.[5] She died in an epidemic of cholera in the summer of 1833, to Johnson's great grief.[2]

The relationship between Johnson and Chinn shows the contradictions within slavery at the time. For one, not only does it indicate that even then that "kin could also be property," but it is an interesting case because Johnson was open about his relationship with Chinn, calling her "my bride" on at least one occasion, with both of them acting like a married couple, and oral tradition recalling that other slaves at Great Crossings worked on their wedding.[21] As part of their relationship, Chinn gained more responsibilities. As she spent much of her time in the "plantation's big house," a two-story brick home, she managed Johnson's estate for at least half of each year, with her purview later expanding to all of his property, even acting as "Richard's representative" and allowing her to handle money.[22] This gave, as historical scholar Christina Snyder argues, some independence, since Johnson told his white employees that Chinn's authority must be respected, and her role allowing her children's lives to be different from "others of African descent at Great Crossings," giving them levels of privileged access within the plantation. This was further complicated by the fact that Chinn was still enslaved but supervised the work of slaves, with the Chinn family never sold or mortgaged off, but she did not have the power to "challenge the institution of slavery or overturn the government that supported it," she only had the power to gain some personal autonomy, with Johnson never legally emancipating her.[23] This may have been because, as Snyder says, liberating her from human bondage would erode "ties that bound her to him" and keeping her enslaved supported his idea of being a "benevolent patriarch."

Johnson and Chinn had two daughters, Adaline (or Adeline) Chinn Johnson and Imogene Chinn Johnson, whom he acknowledged and gave his surname, with Johnson and Chinn preparing them "for a future as free women."[24] Johnson taught them morality and basic literacy, with Julia undoubtedly teaching her own skills, with both later pushing for both of them to "receive regular academic lessons" which he later educated at home to prevent the scorn of neighbors and constituents. Later Johsnon would provide for Adaline and Imogene's education.[2][20] Both daughters married white men. Johnson gave them large farms as dowries from his own holdings.[16] There is confusion about whether Adeline Chinn Scott had children; a 2007 account by the Scott County History Museum said she had at least one son, Robert Johnson Scott.[2] Meyers said that she was childless.[25] There is also disagreement about the year of her death. Bevins writes that Adeline died in the 1833 cholera epidemic.[2] Meyers wrote she died in 1836.[25] The Library of Congress notes that she died in February 1836.[26]

Although Johnson treated these two daughters as his own, according to Meyers, the surviving Imogene was prevented from inheriting his estate at the time of his death. The court noted she was illegitimate, and so without rights in the case.[25] Upon Johnson's death, the Fayette County Court found that "he left no widow, children, father, or mother living." It divided his estate between his living brothers, John and Henry.[27]

Bevins's account, written for the Georgetown & Scott County Museum, says that Adeline's son Robert Johnson Scott; a nephew, Richard M. Johnson, Jr.; and Imogene's family "acquired" Johnson's remaining land after his death.[2]

After Chinn's death, Johnson began an intimate relationship with another family slave.[28] When she left him for another man, Johnson had her picked up and sold at auction. Afterward he began a similar relationship with her sister, also a slave.[28][29]

Political career

.jpg)

Johnson entered politics in 1804, when he was elected to represent Scott County in the Kentucky House of Representatives.[5] He was twenty-three years old.[30] Although the Kentucky Constitution imposed an age requirement of twenty-four for members of the House of Representatives, Johnson was so popular that no one raised questions about his age, and he was allowed to take his seat.[30][31] He was placed on the Committee on Courts of Justice.[32] During his tenure, he supported legislation to protect settlers from land speculators.[5] On January 26, 1807, he delivered an address condemning the Burr conspiracy.[33]

In 1806, Johnson was elected as a Democratic-Republican to the United States House of Representatives, serving as the first native Kentuckian to be elected to Congress.[30][31] At the time of his election in August 1806, he did not meet the U.S. Constitution's age requirement for service in the House (25), but by the time the congressional session began the following March, he met the required age.[30] He was re-elected and served six consecutive terms. From 1807 to 1813, he represented Kentucky's Fourth District.[34]

He secured one of Kentucky's at-large seats in the House from 1813 to 1815, and represented Kentucky's Third District from 1815 to 1819.[34] He continued to represent the interests of the poor as a member of the House. He first came to national attention with his opposition to rechartering the First Bank of the United States.[5]

Johnson served as chairman of the Committee on Claims during the Eleventh Congress (1809–1811).[35] The committee was charged with adjudicating financial claims made by veterans of the Revolutionary War. He sought to influence the committee to grant the claim of Alexander Hamilton's widow to wages which Hamilton had declined when serving under George Washington.[36] Although Hamilton was a champion of the rival Federalist Party, Johnson had compassion for Hamilton's widow; before the end of his term, he secured payment of the wages.[36]

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was extraordinarily popular in Kentucky; Kentuckians depended on sea trade through the port of New Orleans and feared that the British would stir up another Indian war.[37][b] After the election of 1808, Johnson was one of the War Hawks, a group of legislators who clamored for war with the British.[16]

Congress declared war in June 1812, and after its adjournment, Johnson returned to Kentucky to recruit volunteers. So many men responded that he chose only those with horses, and raised a body of mounted rifles.[38] Johnson recruited 300 men, divided into three companies, who elected him major. They merged with another battalion, forming a regiment of 500 men, with Johnson as colonel.[39][c]

Johnson's force was originally intended to join General William Hull at Detroit, but Hull surrendered Detroit on August 16 and his army was captured. Johnson reported to William Henry Harrison, Territorial Governor of Indiana, then in command of the entire Northwest frontier. He was ordered to relieve Fort Wayne in the northeast of the Territory, which was already being attacked by the Indians. On September 18, 1812, Johnson's men reached Fort Wayne in time to save it, and turned back an Indian ambush. They returned to Kentucky and disbanded, going out of their way to burn Potawatomi villages along the Elkhart River.[40]

Johnson returned to his seat in Congress in the late fall of 1812. Based on his experience, he proposed a plan to defeat the mobile, guerrilla warfare of the Indians. American troops moved slowly, dependent on a supply line. Indians would evade battle and raid supplies until the American forces withdrew or were overrun. Mounted riflemen could move quickly, carry their own supplies, and live off the woods. If they attacked Indian villages in winter, the Indians would be compelled to stand and fight for the supplies they used to wage war, and could be decisively defeated. Johnson submitted this plan to President James Madison and Secretary of War John Armstrong, who approved it in principle. They referred the plan to Harrison, who found winter operations impracticable. Johnson was permitted to try the tactics in the summer of 1813; later the US conducted Indian wars in winter with his strategy.[41]

Johnson left Washington, D.C. just before Congress adjourned. He raised one thousand men, nominally part of the militia brigade under Kentucky Governor Isaac Shelby, but largely operating independently. He disciplined his men, required that every man have arms in prime condition and ready to hand, and hired gunsmiths, blacksmiths, and doctors at his own expense. He devised a new tactical system: when any group of men encountered the enemy, they were to dismount, take cover, and hold the enemy in place. All groups not in contact were to ride to the sound of firing, and dismount, surrounding the enemy when they got there. Between May and September, Johnson raided throughout the Northwest, burning the war supply centers of Indian villages, surrounding Indian fighting units and scattering them, killing some Indian warriors each time.[42]

In September, Oliver Hazard Perry destroyed most of the British fleet at the Battle of Lake Erie, taking control of the lake. This put the British army, then at Fort Malden (now Amherstburg, Ontario) out of supply, and threatened to cut it off from the rest of Canada by a landing to the east. The British, under General Henry Procter, withdrew to the northeast, followed by Harrison, who had advanced through Michigan while Johnson kept the Indians engaged. The Indian chiefTecumseh and his tribe, hired as mercenaries, covered the British retreat, but were countered by Johnson, who had been called back from a raid on Kaskaskia that had taken the post where the British had distributed arms and money to their hired Indians.. Johnson's cavalry defeated Tecumseh's main force on September 29, took British supply trains on October 3, and was one of the factors inducing Procter to stand and fight at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, as Tecumseh had been demanding he do. One of Johnson's slaves, Daniel Chinn, accompanied Johnson to the battle.[43]

At the battle itself, Johnson's forces were the first to attack. One battalion of five hundred men, under Johnson's elder brother, James Johnson, engaged the British force of eight hundred regulars; simultaneously, Richard Johnson, with the other, now somewhat smaller battalion, attacked the fifteen hundred Indians led by Tecumseh. There was too much tree cover for the British volleys to be effective against James Johnson; three quarters of the regulars were killed or captured.

The Indians were a harder fight; they were out of the main field of battle, skirmishing on the edge of an adjacent swamp. Richard Johnson eventually ordered a suicide squad of twenty men to ride forward and draw the Indians' fire, planning to charge with the rest as they reloaded. But the ground before the Indian position was too swampy to support many cavalry. Johnson had to order his men to dismount and hold until Shelby's infantry came up. But eventually they broke, and fled into the swamp, during which time Tecumseh was slain, some say by Johnson, others believing it was someone else.[44][45]

Richard Johnson was credited later with killing Tecumseh personally, which he used to become a "career politician" and master of the Great Crossings area.[46] Indian reports were that Tecumseh was killed by a man on horseback, and Johnson was one of the few mounted men at that side of the battle. (His own men had dismounted, and Shelby's were infantry.) Furthermore, Johnson, who had been wounded four times already, had been shot in the shoulder by an Indian chief who was advancing to tomahawk Johnson, when he shot back and killed the Indian instantly with a single pistol shot. A nineteenth-century source asserts that Tecumseh's body was found, near Johnson's hat and scabbard, shot from above (as from horseback), and wounded with Johnson's usual load of two buckshot and a pistol ball.[47][d]

Johnson fell unconscious after this duel and was dragged from the battlefield; in addition to his five wounds, twenty other bullets had hit his horse and gear.[48] But the war in the Northwest was over. Although there was no organized resistance to his presence in Canada, Harrison withdrew to Detroit because of supply problems. (The Canadians would not feed his men.) Johnson eventually recovered, except for a crippled hand, but he was still suffering from his wounds when he returned to the House in February 1814.[17]

On April 4, 1818, an act of Congress requested that the President of the United States present to Johnson a sword in honor of his "daring and distinguished valor" at the Battle of the Thames.[49] Johnson was only one of 14 military officers to be presented a sword by an act of Congress prior to the American Civil War.[50]

In August 1814, British forces attacked Washington, D.C. and burned the White House. Congress formed a committee to investigate the circumstances that allowed Washington to be captured. Johnson chaired this committee, and delivered its final report.[51] After the sacking of Washington, the tide of battle turned against the British, and the Treaty of Ghent ended the war even as Johnson prepared to return to Kentucky to raise another military unit.[52] With the end of the war, he turned his legislative attention to issues such as securing pensions for widows and orphans and funding internal improvements in the West.[17]

Post-war career in the House

Johnson believed that Congressional business was too slow and tedious, and that the per diem system of compensation encouraged delays on the part of members.[53] To remedy this, he sponsored the Compensation Act of 1816. The measure proposed paying annual salaries of $1,500 to congressmen rather than a $6 per diem for the days the body was in session.[54] (At the time, this had the effect of increasing the total compensation from about $900 to $1500. Johnson noted that congressmen had not had a pay increase in 27 years, and that $1500 was less than the salaries of the 28 clerks employed by the government.)[55] Johnson's bill provided that if a congressman was absent, his salary would be reduced proportionally.[55]

The bill passed the House and Senate quickly and was made law on March 19, 1816.[55] But, the measure proved extremely unpopular with voters, in part because it applied to the current Congress.[56][e] Many legislators who supported the bill lost their congressional seats as a result, including Johnson's colleague Solomon P. Sharp from Kentucky. Johnson's popularity in other matters helped him retain his seat. Two days into the next session, he recanted his support for the law.[57] It was repealed in that session, and in its place, legislators passed an increase in the per diem salary.[58]

President James Monroe's first choice for Secretary of War was Henry Clay, who declined the office. When Johnson also declined to serve, the post ultimately went to John C. Calhoun.[5] The result was that Johnson became chair of the Committee on Expenditures where he wielded considerable influence over defense policy in the Department of War during the Fifteenth Congress.[35] In 1817, Congress investigated General Andrew Jackson's execution of two British subjects during the First Seminole War. Johnson chaired the inquiry committee. The majority of the committee favored a negative report and a censure for Jackson. Johnson, a Jackson supporter, drafted a counter report that was more favorable to Jackson and opposed the censure. The ensuing debate pitted Johnson against fellow Kentuckian Henry Clay. Johnson's report prevailed, and Jackson was spared censure.[59] This disagreement between Johnson and Clay, however, marked the beginning of a political separation between the two that lasted for the duration of their careers.[60]

In 1818, Calhoun approved an expedition to build a military outpost near the present site of Bismarck, North Dakota on the Yellowstone River; Johnson awarded the contract to his brother James.[5] Although the Yellowstone Expedition was an ultimate failure and expensive to the U.S. Treasury, the Johnsons escaped political ill will in their home district because the venture was seen as a peacekeeping endeavor on the frontier.[5]

Senator

Johnson announced his intent to retire from the House in early 1818.[61] In December 1818, the state legislature was to elect a replacement for outgoing senator Isham Talbot.[62] Johnson lost the election by twelve votes to William Logan despite the fact that he never officially declared his candidacy.[62] It was reported in the local newspapers that Johnson's friends intended to nominate him for governor in the 1820 election.[62]

Johnson's term in the House expired March 3, 1819, but by August, he had returned to the state legislature where he helped secure passage of a law that abolished imprisonment for debtors in Kentucky.[7] In December 1819, he resigned his post in the state legislature to fill the Senate seat vacated by the resignation of John J. Crittenden.[7] He was re-elected to a full term in 1822, so that in total, his Senate tenure ran from December 10, 1819 to March 4, 1829.[35] In 1821, he introduced legislation chartering Columbian College (later The George Washington University) in Washington, D.C.[7] During this time period, his views on Western expansion were clear. He believed that the US "empire of liberty" should extend across the continent, arguing in debates leading up to the Missouri Compromise that western expansion and emancipation should go hand in hand, acknowledging issues with white racism but advocating for gradual emancipation.[63] Furthermore, he went against the ideas put forward by sympathizers of the Colonization movement, arguing in "favor of meaningfully incorporating people of color into a multiracial empire."[64]

There had been inflation after the War of 1812, and the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States. In these times, when paper currency was privatized, this took the form of wildcat banks. Johnson, like many other Kentuckians, was caught in the ensuing financial collapse, the Panic of 1819. He took a strong part in the politically popular struggle for debt relief, and some form of bankruptcy legislation, called the Relief War, which would help his own problems and those of his neighbors.[65] Johnson knew this politically pressing issue, which he worked on into the 1830s, quite well because it affected him personally. He was in debt himself from his business expenses and support for Western expansion.[66] At the same time, he had other political positions. As the chair of the Committee on Military Affairs, Johnson pushed for higher veterans pensions, "liberal land policy" to make it easier to buy land in the West, and defended Andrew Jackson in the Senate, after the First Seminole War.[67]

Part of Johnson's campaign for relief was the abolition of the practice of debt imprisonment nationwide. It would take him nearly ten years to see this goal accomplished. He first spoke to the issue in the Senate on December 14, 1822, introducing a bill to end the practice, and pointing to the positive effects its cessation had effected in his home state. The bill failed, but Johnson persisted in re-introducing it every year. In 1824, it passed the Senate, but was too late to be acted upon by the House. It passed the Senate a second time in 1828, but again, the House failed to act on it, and the measure died for some years, owing to Johnson's exit from the Senate the next year.[68]

Already known for securing government contracts for himself, as well as his brothers and friends, he offered land to establish the Choctaw Academy, a school devoted to the European-American education of Indians from the Southeast tribes. Johnson had tied to establish an Indian school at Great Crossings in 1818, partnering with the Kentucky Baptist Society, but the school folded in 1821 after it didn't gain support of the federal government or private donors.[69] The new academy would come into being a few years later. The academy, sitting on his farm in Scott County in 1825, was overseen by Johnson, not only was part of treaty negotiations with the Choctaw Nation but appealed to his colleagues as a form "peaceful conquest" or "expansion with honor" as Henry Knox put it.[70][71] Although he never ran afoul of the conflict of interest standards of his day, some of his colleagues considered his actions ethically questionable.[16] Johnson was paid well for the school by the federal government, which gave him a portion of the annuities for the Choctaw. It was promoted by the Baptist Missionary Society as well.[72] Some European-American students also attended the Academy, including his nephew Robert Ward Johnson from Arkansas.[73]

Another pet project Johnson supported was prompted by his friendship with John Cleves Symmes, Jr., who proposed that the Earth was hollow. In 1823, Johnson proposed in the Senate that the government fund an expedition to the center of the Earth. The proposal was soundly defeated, receiving only twenty-five votes in the House and Senate combined.[28]

Johnson served as chairman of the Committee on Post Office and Post Roads during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Congresses. Near the end of his term in the Senate, petitioners asked Congress to prevent the handling and delivery of mail on Sunday because it violated biblical principles about not working on the Sabbath.[16] These petitions were referred to Johnson's committee. In response, Johnson, a practicing Baptist, drafted a report now commonly referred to as The Sunday Mail Report[16][74] In the report, presented to Congress on January 19, 1829, Johnson argued that government was "a civil, and not a religious institution", and as such could not legislate the tenets of any particular denomination.[5] The report was applauded as an elegant defense of the doctrine of separation of church and state. But, Johnson was criticized for conflict of interest in his defense, as he had friends who were contracted to haul mail, and who would have suffered financially from banning of Sunday deliveries.[16]

In 1828, Johnson was an unsuccessful candidate for re-election, owing in part to his relationship with the octaroon slave Julia Chinn, with whom he lived in a common-law marriage.[5] Although members of his own district seemed little bothered by the arrangement, slaveholders elsewhere in the state were not so forgiving.[5] In his own defense, Johnson said, "Unlike Jefferson, Clay, Poindexter and others I married my wife under the eyes of God, and apparently He has found no objections."[8] (Note: The named men were suspected or known to have similar relationships with slave women.)[8] According to Henry Robert Burke, what people objected to was Johnson trying to introduce his daughters to "polite society". People were used to planters and overseers having relationships with slave women, but they were expected to deny them.[8]

Return to the House

After his failed Senatorial re-election bid, Johnson returned to the House, representing Kentucky's Fifth District from 1829 to 1833, and Thirteenth District from 1833 to 1837. During the Twenty-first and Twenty-second Congresses, he again served as chairman of the Committee on Post Office and Post Roads.[35] In this capacity, he was again asked to address the question of Sunday mail delivery. He drew up a second report, largely similar in content to the first, arguing against legislation preventing mail delivery on Sunday.[75] The report, commonly called "Col. Johnson's second Sunday mail report", was delivered to Congress in March 1830.[75]

Some contemporaries doubted Johnson's authorship of this second report.[5] Many claimed it was instead written by Amos Kendall.[76] Kendall claimed he had seen the report only after it had been drafted and said he had only altered "one or two words."[76] Kendall speculated that the author could be Reverend O.B. Brown, but historian Leland Meyer concludes that there is no reason to doubt that Johnson authored the report himself.[76]

Johnson chaired the Committee on Military Affairs during the Twenty-second, Twenty-third, and Twenty-fourth Congresses.[35] Beginning in 1830, there arose a groundswell of public support for Johnson's "pet project" of ending debt imprisonment.[77] The subject began to appear more frequently in President Jackson's addresses to the legislature.[78] Johnson chaired a House committee to report on the subject, and delivered the committee's report on January 17, 1832.[79] Later that year, a bill abolishing the practice of debt imprisonment passed both houses of Congress, and was signed into law on July 14.[80]

Johnson's stands won him widespread popularity and endorsement by George H. Evans, Robert Dale Owen, and Theophilus Fisk for the presidency in 1832, but Johnson abandoned his campaign when Andrew Jackson announced he would seek a second term. He then began campaigning to become Jackson's running mate, but Jackson favored Martin Van Buren instead. At the Democratic National Convention, Johnson finished a distant third in the vice-presidential balloting, receiving only the votes of the Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois delegations; William B. Lewis had to persuade him to withdraw[81]

Election of 1836

After the election of 1832, Johnson continued to campaign for the Vice Presidency which would be available in 1836; he was endorsed by the New York labor leader Ely Moore on March 13, 1833, nine days after Jackson and Van Buren were inaugurated. Moore praised his devotion to freedom of religion and his opposition to imprisonment for debt.[82][f]

William Emmons, the Boston printer, published a biography of Johnson in New York dated July 1833.[83] Richard Emmons, from Great Crossing, Kentucky, followed this up with a play entitled Tecumseh, of the Battle of the Thames and a poem in honor of Johnson. Many of Johnson's friends and supporters – Davy Crockett and John Bell among them – encouraged him to run for president. Jackson, however, supported Vice-President Van Buren for the office. Johnson accepted this choice, and worked to gain the nomination for vice-president.[5]

Emmons' poem provided the line that became Johnson's campaign slogan: "Rumpsey Dumpsey, Rumpsey Dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh."[5] Jackson supported Johnson for vice-president, thinking that the war hero would balance the ticket with Van Buren, who had not served in the War of 1812.[17] Jackson made his decision based on Johnson's loyalty but also the president's anger at the primary rival, William Cabell Rives.[5]

Despite Jackson's support, the party was far from united behind Johnson. Van Buren preferred Rives as a running mate.[5] In a letter to Jackson, Tennessee Supreme Court justice John Catron doubted that "a lucky random shot, even if it did hit Tecumseh, qualifies a man for the vice presidency".[16] Although Johnson was a "widower", after Chinn's death in 1833, there was still dissension related to Johnson's open relationship with a slave.[8] The 1835 Democratic National Convention, in Baltimore, in May 1835, was held under the two-thirds rule, largely to demonstrate Van Buren's wide popularity. Although Van Buren was nominated unanimously, Johnson barely obtained the necessary two thirds of the vote. (A motion was made to change the rule, but it obtained only a bare majority, not two thirds.)

Tennessee's delegation did not attend the convention. Edward Rucker, a Tennessean who happened to be in Baltimore, was picked to cast its 15 votes, so that all the states would endorse Van Buren. Senator Silas Wright, of New York, prevailed upon Rucker to vote for Johnson, giving him just more than twice the votes cast for Rives, and the nomination.[84]

Jackson's faith in Johnson to balance the ticket proved misplaced. In the general election, Johnson cost the Democrats votes in the South, where his relationship with Chinn was particularly unpopular. He also failed to garner much support from the West, where he was supposed to be strong due to his reputation as an Indian fighter and war hero.[16] He even failed to deliver his home state of Kentucky for the Democrats.[16] Regardless, the Democrats still won the popular vote.

When the electoral vote was counted in Congress on February 8, 1837, Van Buren was found to have received 170 votes for president, but Johnson had received only 147 for vice-president.[16] Although Virginia had elected electors pledged to both Van Buren and Johnson, the state's 23 "faithless electors" refused to vote for Johnson, leaving him one electoral vote short of a majority.[5] For the only time, the Senate was charged with electing the Vice President under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment.[16] The vote on 8 February 1837 divided strictly along party lines, with Johnson becoming vice-president by a vote of 36, as opposed to 16 for Whig Francis Granger, with three senators absent.[5]

Vice Presidency

Johnson served as Vice President from March 4, 1837, to March 4, 1841. His term was largely unremarkable, and he enjoyed little influence with President Van Buren.[17] His penchant for wielding his power for his own interests did not abate. He lobbied the Senate to promote Samuel Milroy, whom he owed a favor, to the position of Indian agent.[5] When Lewis Tappan requested presentation of an abolitionist petition to the Senate, Johnson, who was still a slaveholder, declined the request.[5]

As presiding officer of the Senate, Johnson was called on to cast a tie-breaking vote fourteen times, more than all of his predecessors save John Adams and John Calhoun. Despite the precedent set by some of his predecessors, Johnson never addressed the Senate on the occasion of a tie-breaking vote; he did once explain his vote via an article in the Kentucky Gazette.[5]

After the financial Panic of 1837, Johnson took a nine-month leave of absence, during which he returned home to Kentucky and opened a tavern and spa on his farm to offset his continued financial problems.[5][85] Upon visiting the establishment, Amos Kendall wrote to President Van Buren that he found Johnson "happy in the inglorious pursuit of tavern keeping – even giving his personal superintendence to the chicken and egg purchasing and water-melon selling department".[5]

In his later political career, he became known for wearing a bright red vest and tie.[86] He adopted this dress during his term as vice-president when he and James Reeside, a mail contractor known for his drab dress, passed a tailor's shop that displayed a bright red cloth in the window.[87] Johnson suggested that Reeside should wear a red vest because the mail coaches he owned and operated were red.[87] Reeside agreed to do so if Johnson would also.[87] Both men ordered red vests and neckties, and were known for donning this attire for the rest of their lives.[87]

Election of 1840

By 1840, it had become clear that Johnson was a liability to the Democratic ticket. Even former president Jackson conceded that Johnson was "dead weight", and threw his support to James K. Polk.[16][88] President Van Buren stood for re-election, and the Whigs once again countered with William Henry Harrison.[16] Van Buren was reluctant to drop Johnson from the ticket, fearing that dropping the Democrats' own war hero would split the party and cost him votes to Harrison.[16] A unique compromise ensued, with the Democratic National Convention refusing to nominate Johnson, or any other candidate, for vice-president.[5] The idea was to allow the states to choose their own candidates, or perhaps return the question to the Senate should Van Buren be elected with no clear winner in the vice-presidential race.[16]

Undaunted by this lack of confidence from his peers, Johnson continued to campaign to retain his office. Although his campaign was more vigorous than that of Van Buren, his behavior on the campaign trail raised concern among voters. He made rambling, incoherent speeches. During one speech in Ohio, he raised his shirt in order to display to the crowd the wounds he received during the Battle of the Thames. Charges he leveled against Harrison in Cleveland were so poorly received that they touched off a riot in the city.[5]

In the end, Johnson received only forty-eight electoral votes.[89] One elector from Virginia and all eleven from South Carolina voted for Van Buren for president but selected someone other than Johnson for vice-president.[5] Johnson lost his home state of Kentucky again and added to the embarrassment by losing his home district as well.[5]

Later life and death

After his term as vice-president, Johnson returned to Kentucky to tend to his farm and oversee his tavern.[17] He again represented Scott County in the Kentucky House from 1841 to 1843.[7] In 1845, he served as a pallbearer when Daniel Boone was re-interred in Frankfort Cemetery.[16]

Johnson never gave up on a return to public service. He ran an unsuccessful campaign for the U.S. Senate against John J. Crittenden in 1842.[16] He briefly and futilely sought his party's nomination for president in 1844.[16] He also ran as an independent candidate for Governor of Kentucky in 1848, but after talking with the Democratic candidate, Lazarus W. Powell, who had replaced Linn Boyd on the ticket, Johnson decided to drop out and back Powell.[90] Some speculated that the real object of this campaign was to secure another nomination to the vice-presidency, but this hope was denied.[5]

Johnson finally returned to elected office in 1850, when he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives. By this time, however, his physical and mental health was already failing. On November 9, the Louisville Daily Journal reported that "Col. R. M. Johnson is laboring under an attack of dementia, which renders him totally unfit for business. It is painful to see him on the floor attempting to discharge the duties of a member. He is incapable of properly exercising his physical or mental powers."[89]

He died of a stroke on November 19, just two weeks into his term.[16] He was interred in the Frankfort Cemetery, in Frankfort, Kentucky.[35] Ruling that his surviving daughter Imogene was illegitimate, the Frankfort County Court split his estate between his brothers John and Henry.[91]

Legacy

The counties of five U.S. states bear Johnson's name, namely in Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky,[92] Missouri, and Nebraska.[93] Richard Mentor Johnson is also the namesake of Dick Johnson Township, Indiana.[94]

His political prominence led to a family dynasty: his brothers James and John Telemachus Johnson, and his nephew Robert Ward Johnson were all elected to the House of Representatives, the first two from Kentucky, and Robert from Arkansas. Robert was later elected as a Senator before the Civil War.[35]

See also

- The Family (Arkansas politics)

- Thomas S. Hinde

- List of federal political sex scandals in the United States

Notes

^[a] Emmons and Langworthy, contemporary sources, give 1781, and Pratt and Sobel accept this date; this has the effect of making him born in Kentucky, which would be a reason to invent it.

^[b] Carr also sees, as background motives, the British hostility to slavery, and a consequent wish to disentangle Britain from the United States.

^[c] This is chiefly Langworthy's account, but both 300 and 500 men are recorded in other sources.

^[d] French is the nineteenth century source, but Berton says it is uncertain which body was Tecumseh's. Few whites had ever seen him.

^[e] Today, this would violate the Twenty-seventh Amendment.

^[f] Note that Emmons, like Langworthy, was published in New York City.

References

- ↑ Larry J. Sabato; Howard R. Ernst (May 14, 2014). Encyclopedia of American Political Parties and Elections. Infobase Publishing. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-4381-0994-7. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

in 1836...the Virginia electors abstained rather than vote for Democratic vice presidential nominee Richard Johnson"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bevins, Richard M Johnson narrative: Personal and Family Life

- ↑ Christina Snyder, Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers & Slaves in the Age of Jackson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 42.

- ↑ Snyder,Great Crossings, p. 42-43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Hatfield, Vice Presidents (1789–1993)

- ↑ Snyder,Great Crossings, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kleber, p. 475

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burke, Window to the Past

- 1 2 3 Meyer, p. 22

- 1 2 3 4 Meyer, p. 23

- 1 2 3 Meyer, p. 24

- ↑ Pratt, p. 82; McManus

- ↑ Emmons, p.9, Langworthy, p.7; records from Meyer.

- ↑ Snyder,Great Crossings, p. 43-44.

- 1 2 ""General Information about the Museum"". Archived from the original on May 13, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2016., Georgetown & Scott County Museum, accessed 11 November 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Stillman, Eccentricity at the Top

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Richard M. Johnson (1837–1841)

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 51-53.

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 3-4, 8-9.

- 1 2 Mills, The Vice-President and the Mulatto

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 54-56. Their social role as a married couple was even recognized by neighbors.

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 56-58.

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 59-60, 62-63. Despite this, Johnson did liberated other black slaves.

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 53, 63, 66-67.

- 1 2 3 Meyer, p. 322

- ↑ "An Affecting Scene in Kentucky" Archived 2008-06-19 at the Wayback Machine., political print (c.1836), Harper's Weekly, at Library of Congress, accessed 12 November 2013

- ↑ Meyer, pp. 322–323

- 1 2 3 McQueen, p. 19

- ↑ Stimpson, p. 133

- 1 2 3 4 Langworthy, p. 9

- 1 2 Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 44.

- ↑ Meyer, p. 51

- ↑ Meyer, p. 58

- 1 2 The Political Graveyard

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "JOHNSON, Richard Mentor - Biographical Information".

- 1 2 Langworthy, p. 10

- ↑ Carr, pp. 299–300

- ↑ Langworthy, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Langworthy, p. 14; Pratt, pp. 86-8

- ↑ Meyer, p.92; Pratt, p. 89

- ↑ Pratt, pp. 90-1; cf. Langworthy, p.15, Emmons, p. 22.

- ↑ Pratt, p. 92-4

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 7. Julia Chinn, an enslaved black woman, sought more liberty for herself and children was different from Daniel, her brother.

- ↑ Pratt, pp.94-96

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 44-47.

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 2.

- ↑ Emmons, p.35; Pratt, p.95-6; Brown, pp. 197-204; French, Vol II, p. 253; Kye

- ↑ Langworthy, p. 25

- ↑ Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, 1789–1903. Francis B. Heitman. Vol. 1, pg. 576.

- ↑ Heitman. pg. 46.

- ↑ Langworthy, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Langworthy, p. 31

- ↑ Meyer, p. 168

- ↑ Meyer, p. 170

- 1 2 3 Meyer, p. 171

- ↑ Hatfield; Cleaves, p. 237

- ↑ Meyer, p. 172

- ↑ Meyer, p. 175

- ↑ Langworthy, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Meyer, p. 181

- ↑ Meyer, p. 183

- 1 2 3 Meyer, p. 185

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 7.

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings," p. 61.

- ↑ Stillman, Schlesinger, 30-2

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 48-49.

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings," p. 47-48.

- ↑ Meyer, pp. 282–287

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 50-51.

- ↑ Snyder, Great Crossings, p. 38-40, 69.

- ↑ Foreman, The Choctaw Academy

- ↑ [ Ethel McMillan, "FIRST NATIONAL INDIAN SCHOOL: THE CHOCTAW ACADEMY"], Chronicles of Oklahoma, accessed 12 November 2013

- ↑ "Robert Ward Johnson (1814–1879)", Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture, accessed 12 November 2013

- ↑ Langworthy, p. 39

- 1 2 Langworthy, p. 40

- 1 2 3 Meyer, p. 262

- ↑ Meyer, pp. 287–288

- ↑ Meyer, p. 288

- ↑ Meyer, pp. 288–289

- ↑ Meyer, p. 289

- ↑ Hatfield; Schlesinger, p.142.

- ↑ Emmons, p. 61ff, which abstracts Moore's speech and other documents.

- ↑ Emmons, p.4; Schlesinger, p. 142.

- ↑ Lynch, p. 383f

- ↑ McQueen, pp. 19–20

- ↑ Meyer, p. 310

- 1 2 3 4 Meyer, p. 311

- ↑ McQueen, p. 20

- 1 2 McQueen, p. 21

- ↑ Starling in Kentucky: History of Henderson County

- ↑ Meyers (1932)

- ↑ The Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society, Volume 1. Kentucky State Historical Society. 1903. p. 35.

- ↑ Blevins, Danny K. (20 February 2008). Van Lear. Arcadia Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4396-3534-6.

- ↑ Blanchard, Charles (1884). Counties of Clay and Owen, Indiana: Historical and Biographical. F.A. Battey & Company. p. 83.

Bibliography

- Anonymous:

- Index to Politicians: Johnson, O to R. The Political Graveyard. Retrieved on January 3, 2008.

- "Richard Mentor Johnson (1837–1841)." University of Virginia. Retrieved on January 4, 2008.

- Pierre Berton, Flames across the Border, Little Brown, 1981.

- Ann Bevins, "Richard M Johnson narrative: Personal and Family Life" at Archive.is (archived August 18, 2007), Georgetown and Scott County Museum, 2007, Retrieved on March 25, 2008.

- Henry Robert Burke. "Window to the Past", Lest We Forget Communications. Retrieved on January 3, 2008.

- "By His Hand the Chief Tecumseh Fell" (PDF), The New York Times, August 13, 1895. Reprint from the Philadelphia Times. Retrieved on January 3, 2008.

- Albert Z. Carr, The Coming of War; an account of the remarkable events leading to the War of 1812. Doubleday, 1960.

- Freeman Cleaves, Old Tippecanoe; William Henry Harrison and his Time. Scribner, 1939.

- William Emmons, Authentic Biography of Colonel Richard M. Johnson, of Kentucky. New York; H. Mason., 1833.

- Carolyn Thomas Foreman "The Choctaw Academy". The Chronicles of Oklahoma 6 (4), December 1928. Oklahoma Historical Society. January 3, 2008.

- James Strange French, Elkswatawa, Harper Brothers, 1836. A historical novel with endnotes based on the author's research and interviews.

- Mark O. Hatfield, ed.: "Richard Mentor Johnson, 9th Vice President (1837–1841)", Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993 (PDF), Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997: pp. 121–131. Retrieved on January 3, 2008.

- John E. Kleber. "Johnson, Richard Mentor", in John E. Kleber, ed: The Kentucky Encyclopedia, Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter, Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1992. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- Asahel Langworthy A Biographical Sketch of Col. Richard M. Johnson, of Kentucky. New York City, New York: Saxton & Miles. Retrieved on January 3, 2008.

- Denis Tilden Lynch: An Epoch and a Man, Martin Van Buren and his Times, Liveright, 1929

- Edgar J. McManus, "Richard Mentor Johnson", American National Biography. Online version posted February 2000, accessed April 5, 2008.

- Keven McQueen, "Richard Mentor Johnson: Vice President", in Offbeat Kentuckians: Legends to Lunatics, Ill. by Kyle McQueen, Kuttawa, Kentucky: McClanahan Publishing House. ISBN 0-913383-80-5.

- Leyland Winfield Meyer The Life and Times of Colonel Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky. New York, Columbia University, 1932. Doctoral thesis; published in the series, Studies in history, economics and public law.

- David Mills. "The Vice-President and the Mulatto", The Huffington Post, 26 April 2007, Retrieved on 5 January 2008.

- Fletcher Pratt, "Richard M. Johnson: Rumpsey-Dumpsey", Eleven Generals; Studies in American Command, New York; William Sloane Assoc., 1949, pp. 81–97.

- Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Age of Jackson, Little Brown, 1945.

- Robert Sobel, "Johnson, Richard Mentor", Biographical Directory of the United States Executive Branch, 1774–1989. Greenwood Press, 1990 ISBN 0-313-26593-3. Retrieved on January 5, 2008.

- Edmund Lyne Starling, History of Henderson County, Kentucky. Henderson, Kentucky, 1887; repr. Unigraphic, Evansville, Indiana, 1965. Accessed April 5, 2008.

- Michael Stillman, "Eccentricity at the Top: Richard Mentor Johnson." Americana Exchange Monthly, January 2004. Retrieved on January 3, 2008.

- George William Stimpson, "A book about American politics." 1952. Retrieved on August 11, 2010.

Further reading

- Carolyn Jean Powell, "What's love got to do with it?" The Dynamics of Desire, Race and Murder in the Slave South, January 2002, Doctoral dissertation #AAI3039386, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

- Richard Shenkman, Kurt Reiger (2003). "The Vice-President Who Sold His Mistress At Auction", One-Night Stands with American History: Odd, Amusing, and Little-Known Incidents. HarperCollins, pp. 71–72. ISBN 0-06-053820-1.

- George Stimpson, A Book about American Politics New York; Harper 1952, p. 133.

- William Hobart Turner, Edward J. Cabbell Blacks in Appalachia. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1985. pp. 75–80. ISBN 0-8131-0162-X.

- Which Vice President of the United States Was the Father Of...?. Black Voices News. Posted January 20, 2005

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Johnson, Richard Mentor. |

- United States Congress. "Richard Mentor Johnson (id: J000170)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Richard Mentor Johnson at Find a Grave

- The Sunday Mail Report, authored and delivered by Johnson to the Senate on January 19, 1829 (related to delivery of mail on the Sabbath)

- "An Affecting Scene in Kentucky", a political print (c.1836) attacking Johnson for his relationship with Julia Chinn, published in Harper's Weekly, at Library of Congress

- "Carrying the War into Africa", an 1836 political print attacking Johnson for his relationship with Julia Chinn, published in Harper's Weekly, at Library of Congress