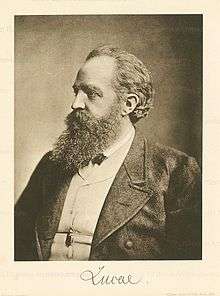

Richard Lucae

| Richard Lucae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Johannes Theodor Volcmar Richard Lucae April 12, 1829 Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died |

November 26, 1877 (aged 48) Berlin, German Empire |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse(s) | Marie Schacht |

| Buildings |

Alte Oper Borsig Palace |

Richard Lucae (12 April 1829 – 26 November 1877 ; full name: Johannes Theodor Volcmar Richard Lucae) was a German architect and from 1873 director of the Berliner Bauakademie.

Early life

Richard Lucae came from an old Berlin pharmacy family. His father was Dr. Phil. h.c. August Friedrich Theodor Lucae (1800 – 1848), pharmacist and owner of the Rothen Adler-Apotheke. His mother was Caroline Lucae, born Wendel (1803 – 1870), daughter of Johann Georg Wendel (1754 – 1834), a professor of drawing arts at the Gymnasium in Erfurt. One of Richard's siblings was noted otologist Dr. August Lucae. Richard's early diverse artistic inclinations were greatly influenced by his uncle, August Soller, a Prussian government construction officer and an important architect of the Schinkel school.[1]

Education

Lucae received training as a surveyor 1847–49. In 1850 he began studies in plasterwork at the Berlin Academy of Architecture (German: Berliner Bauakademie) at the instigation of Johann Gottfried Schadow. He could not pass the entrance examination, so Schadow asked him to simply paint a human ear from memory. When Lucae was able to do it with ease, Schadow admitted him to the class contrary to all the rules.[2] Lucae completed his studies in 1852 and then received practical experience in the construction of Cologne Cathedral from 1853 to 1855. He then returned to the Bauakademie for advanced studies (1855–1859), taught there from 1859 onward, joined the academic committee in 1863, and in 1873 became its Director.[1]

Career

Richard Lucae's first complete work is the Church of the Resurrection at Kattowitz, in the Prussian Province of Silesia. Built in cooperation with architect Friedrich August Stüler, the foundation stone was laid on July 17, 1856. The hall building was completed in Rundbogenstil, the then popular German Neo-Renaissance architectural style. Apart from a Romanesque Revival and Art Nouveau transept added in 1900, the core of the building is Lucae's, including the main tower, the apse, part of the nave, the façade, and the rose window.

Residential buildings

After a study journey to Italy in 1859, Lucae was at first unable to find work in Berlin. All public building was tightly controlled by the Prussian government. He therefore started his own architectural business and focused on private residential buildings, such as Villa Kamel (1860) and Villa Siemens (1874-76). He then began work on the monumental Borsig Palace (1875–77), completed for industrialist Albert Borsig, one of the grandest Italianate villas ever built in Germany[3] Its walls, enlivened with sculpted window aediculae, also marked a new period in Berlin's architectural history.[1]

Public buildings

Richard Lucae's residential work solidified his reputation and brought him into contact with prominent industrialists of the period. He went on to win design competitions for large public projects in 1873, including the Magdeburg Stadttheater (built 1873–76) and the Alte Oper in Frankfurt am Main (built 1873–1888). The floor plan of the Opera was influenced by the style of Gottfried Semper and the panther quadriga on the Renaissance-style building recalls the famous Semper Opera House in Dresden.[4] In 1874 Lucae began plans for the complete reconstruction of the interiors of the Bauakademie itself, which were complete in 1875.

In 1876 the new German government initiated plans to create theKöniglich Technische Hochschule Charlottenburg (Royal Technical University Charlottenburg) in a merger of the Bauakademie and the Königliche Gewerbeakademie (Royal Trade Academy). Richard Lucae was called upon to design the new main building for the university, at that time the largest construction project in Berlin. He completed the grand Neo-Renaissance plans shortly before his death, with architect Friedrich Hitzig and master builder Julius Raschdorff making alterations during execution of the project. The new university opened in 1879.[1][5]

Other work

Lucae was a prolific lecturer and writer. He became a critic of the existing architectural styles and deplored housing of the era for its lack of natural lighting, ventilation, and functionality.[6] In particular he was fascinated by the new iron and glass buildings exemplified by the Crystal Palace. In contrast to conservative architects of the day, Lucae embraced this technology as a new way of defining architectural space.[7]

By 1877 he was also serving as a Privy Councillor in the Prussian government's Technical Construction Department and was a member of both the Prussian Academy of Arts (German: Kunstakademie) and the Art Association (German: Kunstverein). He was friends with Theodor Fontane and F. Kugler through his membership in the literary club Tunnel über der Spree, which influenced literary life in Berlin for more than seventy years.[8]

One of Lucae's students at the Bauakademie was Alfred Messel, who became one of the most well-known German architects at the turn of the 20th century[9] He created new architectural style which bridged the transition from historicism to modernism, reflected in his designs for such buildings as the Pergamon Museum and Wertheim department store.[10]

Legacy

Several of Richard Lucae's buildings went on to lead interesting lives in the history of Germany. Many were subsequently damaged or destroyed during World War II, with a few repaired or restored. His most notable buildings and their current status include:

- All of the private homes and villas Lucae built in Berlin were destroyed.[8]

- The Alte Oper became a venue for important world premiers, including Engelbert Humperdinck's Sleeping Beauty in 1902 and Carl Orff's Carmina Burana in 1937. The building was burnt to a shell during the bombing of Frankfurt on the night of March 23, 1944. In 1952 interim measures were taken to prevent the ruin from collapsing entirely. There were plans to demolish it and build an office block, but a citizen's initiative began in 1953 to save what became known as "the most beautiful ruin in Germany."[11] Reconstruction proceeded slowly and the restored, modernized building was reopened on August 28, 1981, in a gala concert featuring Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 8 attended by the President of Germany.[4]

- The Bauakademie burnt during the bombing of Berlin on February 23, 1945. It was partially repaired in 1951 to become the East German Bauakademie der DDR. In 1962 it was demolished to make room for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of East Germany. That building was in turn demolished in the 1990s after German reunification. In 2004 the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation sponsored the construction of simulated canvas façade of the original Bauakademie to give an impression of its volume and form. Sculptors also replicated a corner of the building with molded bricks and terra cotta. Within the structure the former Red Room on the first floor was modeled and used for events and exhibitions.[12] On 11 November 2016 the Bundestag released EUR 62 million to reconstruct the Bauakademie.[13]

- Borsig Palace never served as a residence for Albert Borsig since he died shortly after its completion. By 1904 it was the headquarters of the Prussian Mortgage Bank (German: Preußische Pfandbriefbank). The German government purchased the palace in 1933 to house the offices of Vice-Chancellor of Germany Franz von Papen. One year later, dramatic scenes relating to the Night of the Long Knives played out in its rooms. The building became the new headquarters for the SA (Sturmabteilung) and in 1938 it was incorporated into Adolf Hitler's New Reich Chancellery by Albert Speer. The entire complex was destroyed during the Battle of Berlin in 1945 and the ruins were demolished by Soviet occupation forces in 1947.[14]

- Villa Joachim was rededicated as the new home of Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research (German: Institut für Sexualwissenschaft) on July 6, 1919. It was the first, and until after the war, the only such institution of its kind. The Institute was visited by 20,000 people each year and contained a unique library on sexuality.[15] In May, 1933, the Deutsche Studentenschaft attacked the Institute, hauling the library and archives out to be burned in the streets. The building was then seized by the Nazi government for its own uses. It was destroyed in a bombing raid on the night of November 22–23, 1943, and the rubble was cleared away in 1950.[16]

- The Technical University Berlin was also severely damaged in the bombing of November 22–23, 1943. The central northern wing was a ruin and replaced by a flat office block in the 1960s. The rear wings and internal courtyards were externally restored to their original appearance.[17][18]

- The tombstone Richard Lucae designed for himself and his family in the Stahnsdorf Southwest Cemetery (German: Südwestfriedhof der Berliner Synode) had been swept away by 1946. In 2012 a new memorial to him and his wife was dedicated by the non-profit society "Friends of the Ivy", funded by the International Building Academy Berlin, the Technical University of Berlin Museum of Architecture, and others. The new memorial stone is located on his original grave.[19]

List of works

- 1856–58: Church of the Resurrection, Katowice (extant)

- 1861–62: Villa Heckmann, Berlin (destroyed)[20]

- 1861–63: Villa Stoltmann, Berlin (destroyed)

- 1868–70: Villa Henschel, Kassel (demolished during the depression, 1932)[21]

- 1870–71: Villa Joseph Joachim, Berlin (damaged 1945, demolished 1950)

- 1872–73: Home of Dr. August Lucae, Lützowplatz, Berlin (destroyed 1943)

- 1872–76: State Theatre in Magdeburg (destroyed 1944)

- 1873–74: Villa von Heyden, Berlin

- 1873–74: Villa Werner Siemens, Berlin-Charlottenburg (destroyed 1944)

- 1873–80: Alte Oper, Frankfurt am Main (destroyed 1944, rebuilt 1981)

- 1874–75: Reconstruction of the Bauakademie, Berlin (damaged 1943, partially restored 1951, demolished 1962)

- 1875–78: Borsig Palace at Voßstraße 1, Berlin (damaged 1945, demolished 1947)

- 1875–78: Extension for the Prussian Ministry of Public Works, Voßstraße 35, Berlin (destroyed 1944)

- 1876–77: Technical University of Berlin (damaged 1943, partially rebuilt 1965)

- Chemistry Laboratory, Gewerbeakademie, Berlin (destroyed)

- Schloss von Homeyer, Ranzin

- Schloss Kuhnau

- Schloss Schönfeld

Writings

- Lucae, Richard (1869): "About the Power of Space in Architecture." Zeitschrift für Bauwesen (Journal of Construction). 19. Berlin: Ernst and Korn. pp. 295–306.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Börsch-Supan, Eva (1987), "Lucae, Richard", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 15, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 268–269; (full text online) retrieved 11 Jan 2017.

- ↑ Fontane, Theodor (1882): "Saalow, ein Kapitel vom alten Schadow" in Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg IV: Spreeland. Berlin: Hofenberg (reprinted 2016). ISBN 9783843047227.

- ↑ Kolinsky, Eva and Van der Will, Wilfried (1998): The Cambridge Companion to Modern German Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521568708. p. 283

- 1 2 "Chronik und Historie" (in German). Alte Oper Frankfurt, 2017, retrieved 13 Jan 2017.

- ↑ Dorling Kindersley Ltd (2016): DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Berlin New York: DK Publishing. p. 159 ISBN 978-1465461612.

- ↑ Mallgrave, H.F. (2009): Modern Architectural Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673--1968. Cambridge University Press. p 178 ISBN 978-1-13-944340-1

- ↑ Lucae, pp. 265-306

- 1 2 NDB, p. 269

- ↑ Bedoire, p. 254

- ↑ Blauert

- ↑ Pond, Elizabeth. "Frankfurt reopens opera house - 'the most beautiful ruin in Germany'" (in English).The Christian Science Monitor. 1 Sep 1981, retrieved 13 Jan 2017.

- ↑ "Kein Exportschlager für Baukultur: Bauakademie-Attrappe in Berlin fertig" (in German). BauNetz, 8 Nov 2004, retrieved 13 Jan 2017.

- ↑ "62 Millionen für Wiederaufbau der Schinkelschen Bauakademie". Berliner Morgenpost. 11 Nov 2016, retrieved 13 Jan 2016

- ↑ Demps, pp. 141f

- ↑ Oosterhuis, Harry, ed. "Homosexuality and Male Bonding in Pre-Nazi Germany: Transcripts from Der Eigene, the first gay journal in the world." Journal of Homosexuality Volume 1991, Part 2. LCCN 91027666

- ↑ Eshbach, Robert W. "Villa Joachim, Berlin." Joseph Joachim, Biography and Research. University of New Hampshire, 26 Sep 2014, retrieved 12 Jan 2017.

- ↑ Dorling, p. 159

- ↑ Zick, p. 9

- ↑ "Richard Lucae and Eilhard Mitscherlin" (in German). Gemeinnütziger Förderverein EFEU e.V., 2012, retrieved 12 Jan 2017.

- ↑ "Villa Heckman." Europeana. Retrieved 26 Jan 2017.

- ↑ "Abriss der Henschel-Villa in der Krise." Hessische/Niedersächsische Allgemeine 07 Jun 2010. Retrieved 26 Jan 2017.

References

- Börsch-Supan, Eva (1987), "Lucae, Richard", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 15, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 268–269; (full text online)

- Bedoire, Fredric (2004). The Jewish Contribution to Modern Architecture, 1830-1930 Translated by Robert Tanner. Jersey City: KTAV Publishing House, Inc. ISBN 9780881258080

- Blauert, Elke; Habel, Robert; Nägelke, Hans-Dieter, eds. (2009). Alfred Messel (1853-1909): Visionär der Großstadt. Munich: Edition Minerva. ISBN 9783938832530

- Demps, Laurenz (2000). Berlin-Wilhelmstraße. A Topography Prussian-German Power (in German). Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 3rd Edition. ISBN 3-86153-228-X

- Dorling Kindersley Ltd (2016). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Berlin New York: DK Publishing. ISBN 9781465461612

- Fontane, Theodor (1882). "Saalow, ein Kapitel vom alten Schadow" in Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg IV: Spreeland. Berlin: Hofenberg (reprinted 2016). ISBN 9783843047227.

- Kolinsky, Eva and Van der Will, Wilfried (1998). The Cambridge Companion to Modern German Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521568708

- Mallgrave, H.F. (2009). Modern Architectural Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673--1968. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139443401

- Zick, Wolfgang (2009). Ausstellung 125 Jahres Wissen im Zentrum: Entstehung und Bedeutung (in German). Berlin: Universitätbibliothek Technische Universität Berlin. ISBN 9783798321809 PDF online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard Lucae. |

- Inventory of Works by Richard Lucae, from the Architecture Museum of the Technical University Berlin