Richard Bong

| Richard Ira Bong | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | "Bing Bong", and "Ace of Aces" |

| Born |

September 24, 1920 Superior, Wisconsin, United States |

| Died |

August 6, 1945 (aged 24) North Hollywood, California, United States |

| Buried | Poplar, Wisconsin, United States |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1941–1945 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit | 49th Fighter Group, V Fighter Command |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

Richard Ira "Dick" Bong (September 24, 1920 – August 6, 1945) was a United States Army Air Forces major and Medal of Honor recipient in World War II. He was one of the most-decorated American fighter pilots and the country's highest-scoring flying ace in the war, being credited with shooting down 40 Japanese aircraft. All of his aerial victories were in the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter. He died in California while testing a jet aircraft shortly before the Japanese surrendered and the war ended.

Early life

Bong, the son of Swedish immigrants, grew up on a farm in Poplar, Wisconsin, as one of nine children. He became interested in aircraft at an early age and was an avid model builder.

He began studying at Superior State Teachers College (the current-day University of Wisconsin–Superior) in 1938. While there, Bong enrolled in the Civilian Pilot Training Program and also took private flying lessons. On May 29, 1941, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps Aviation Cadet Program. One of his flight instructors was Captain Barry Goldwater (later Senator from Arizona).

U.S. Army Air Corps

Bong's ability as a fighter pilot was recognized at training in northern California. He was commissioned a second lieutenant and awarded his pilot wings on January 19, 1942. His first assignment was as an instructor (gunnery) pilot at Luke Field, Arizona from January to May 1942. His first operational assignment was on May 6 to the 49th Fighter Squadron (FS), 14th Fighter Group at Hamilton Field, California, where he transitioned into the twin-engine Lockheed P-38 Lightning.

On June 12, 1942, Bong flew very low ("buzzed") over a house in nearby San Anselmo, the home of a pilot who had just been married. He was cited and temporarily grounded for breaking flying rules, along with three other P-38 pilots who had looped around the Golden Gate Bridge on the same day.[1] For looping the Golden Gate Bridge, flying at a low level down Market Street in San Francisco, and blowing the clothes off of an Oakland woman's clothesline, Bong was reprimanded by General George C. Kenney, commanding officer of the Fourth Air Force, who told him, "If you didn't want to fly down Market Street, I wouldn't have you in my Air Force, but you are not to do it any more and I mean what I say." Kenney later wrote, "We needed kids like this lad."[2] In all subsequent accounts, Bong denied flying under the Golden Gate Bridge.[3] Nevertheless, Bong was still grounded when the rest of his group was sent without him to England in July 1942. Bong then transferred to another Hamilton Field unit, 84th Fighter Squadron of the 78th Fighter Group. From there, Bong was sent to the Southwest Pacific Area.

On September 10, 1942, Lt. Bong was assigned to the 9th Fighter Squadron, which was flying P-40 Warhawks, based at Darwin, Australia. In November, while the squadron waited for delivery of the scarce P-38s, Bong and other 9th FS pilots were reassigned temporarily to fly missions and gain combat experience with the 39th Fighter Squadron, 35th Fighter Group, based in Port Moresby, New Guinea. On December 27, Bong claimed his initial aerial victory, shooting down a Mitsubishi A6M "Zero", and a Nakajima Ki-43 "Oscar" over Buna (during the Battle of Buna-Gona).[4] For this action Bong was awarded the Silver Star.

Bong rejoined the 9th FS, then equipped with P-38s, in January 1943; the 49th FG was based at Schwimmer Field near Port Moresby, New Guinea. In April, he was promoted to first lieutenant.[5] On July 26, Bong shot down four Japanese fighters over Lae, an accomplishment that earned him the Distinguished Service Cross. In August, he was promoted to captain.[5] While on leave to the United States the following November and December, Bong met Marge Vattendahl at a Superior State Teachers' College homecoming event and began dating her.

After returning to the Southwest Pacific in January 1944, he named his P-38 "Marge" and adorned the nose with her photo.[6] On April 12, Captain Bong had shot down his 26th and 27th Japanese aircraft, surpassing Eddie Rickenbacker's American record of 26 credited victories in World War I. Soon afterwards, he was promoted by General George Kenney to major and dispatched to the United States to see General Arnold who gave him a leave.[7][5] After visiting training bases and going on a 15-state bond promotion tour, he returned to New Guinea in September. He was assigned to the V Fighter Command staff as an advanced gunnery instructor with permission to go on missions but not to seek combat;[8] Bong continued flying from Tacloban, Leyte, during the Philippines campaign, and increased his official air-to-air victory total on December 17 to 40.

Bong considered his gunnery accuracy to be poor, so he compensated by getting as close to his targets as possible to make sure he hit them. In some cases he flew through the debris of exploding enemy aircraft, and on one occasion actually collided with his target, which he claimed as a "probable" victory.

Upon the recommendation of General Kenney who was the Far East Air Force commander, Bong received the Medal of Honor from General Douglas MacArthur in a special ceremony in December 1944. Bong's Medal of Honor citation states that he flew combat missions despite his status as an "instructor", which was one of his duties as standardization officer for V Fighter Command. His rank of major would have qualified him for a squadron command, but he always flew as a flight (four-plane) or element (two-plane) leader.

In January 1945, General Kenney sent America's ace of aces home for good. Bong married Marjorie Vattendahl on February 10, 1945.[9] He participated in numerous PR activities, such as promoting the sale of war bonds.

Death

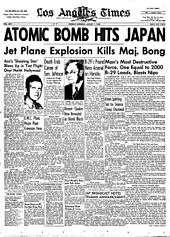

Bong then became a test pilot assigned to Lockheed's Burbank, California, plant, where he flew P-80 Shooting Star jet fighters at the Lockheed Air Terminal. On August 6, 1945, the plane's primary fuel pump malfunctioned during takeoff on the acceptance flight of P-80A 44-85048. Bong either forgot to switch to the auxiliary fuel pump, or for some reason was unable to do so.[10] Bong cleared away from the aircraft, but was too low for his parachute to deploy. The plane crashed into a narrow field at Oxnard St & Satsuma Ave, North Hollywood. His death was front-page news across the country, sharing space with the first news of the bombing of Hiroshima.[11]

At the time of the crash, Bong had accumulated four hours and fifteen minutes of flight time (totaling 12 flights) in the P-80. The I-16 fuel pump was a later addition to the plane (after an earlier fatal crash) and Bong himself was quoted by Captain Ray Crawford (another P-80 test/acceptance flight pilot who flew the day Bong was killed) as saying that he had forgotten to turn on the I-16 pump on an earlier flight.[12]

In his autobiography, Chuck Yeager also writes, however, that part of the ingrained culture of test flying at the time, due to the fearsome mortality rates of the pilots, was anger directed at pilots who died in test flights, to avoid being overcome by sorrow for lost comrades. Bong's brother Carl (who wrote his biography) questions the validity of reported circumstance that Bong repeated the same mistake so soon after mentioning it to another pilot. Carl's book—Dear Mom, So We Have a War (1991)—contains numerous reports and findings from the crash investigations.

Major Richard Ira Bong is buried in a Poplar, Wisconsin cemetery.[13]

Victory credits

| Date[14] | Kills[14] | Location/Comment |

|---|---|---|

| December 27, 1942 | 2 | over Buna |

| January 7, 1943 | 2 | Nakajima Ki-43 "Oscars" over Lae |

| January 8, | 1 | over Lae Harbor, ace status |

| March 3, | 1 | Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" during Battle of the Bismarck Sea |

| March 11, | 2 | "Zeroes" |

| March 29, | 1 | heavy bomber; promoted to 1st Lieutenant. |

| April 14, | 1 | bomber, over Milne Bay. Awarded Air Medal. |

| June 12, | 1 | "Zero", over Bena Bena |

| July 26, | 4 | fighters, on escort over Lae; awarded DSC |

| July 28, | 1 | "Oscar", on escort over New Britain. |

| September 6, | 0 | claimed two bombers, not confirmed; crash-landed at Mailinan airstrip |

| October 2, | 1 | Mitsubishi Ki-46 "Dinah", over Gasmata |

| October 29, | 2 | "Zeros", over Japanese airfield at Rabaul |

| November 5, | 2 | "Zeros", over enemy airfield at Rabaul |

| December 1943-January 1944: On leave in Wisconsin | ||

| February 1944: assigned to Fifth Air Force Fighter Command HQ, but allowed to "free-lance". | ||

| February 15, | 1 | Kawasaki Ki-61 "Tony" off Cape Hoskins, New Britain |

| February 28, | 0 | destroyed a Japanese transport plane on the runway at Wewak, New Guinea |

| March 3, | 2 | Mitsubishi Ki-21 "Sally" bombers, over Tadji, New Guinea |

| April 3, | 1 | fighter over Hollandia, 25th credit |

| April 12, | 3 | surpassed Eddie Rickenbacker's U.S. record of 26 kills |

| May–July 1944: on leave in U.S., made publicity tours | ||

| October 10, | 2 | Nakajima J1N "Irving" and "Oscar" |

| October 27, | 1 | "Oscar" |

| October 28, | 2 | "Oscars" off Leyte |

| November 10, | 1 | "Oscar" over Ormoc Bay |

| November 11, | 2 | Recommended for Medal of Honor. |

| December 7, | 2 | "Sally" and Nakajima Ki-44 "Tojo", covering U.S. landings at Ormoc |

| December 15, | 1 | "Oscar" |

| December 17, | 1 | "Oscar" over Mindoro. |

Units

Bong's Army Air Forces units:

39th Fighter Squadron

39th Fighter Squadron 49th Fighter Squadron

49th Fighter Squadron 84th Fighter Squadron

84th Fighter Squadron 9th Fighter Squadron

9th Fighter Squadron

Military awards

Bong's military decorations and awards include:

| ||

| United States Army Air Forces pilot badge | |||

| Medal of Honor | Distinguished Service Cross | Silver Star w/ one Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster | |

| Distinguished Flying Cross w/ one Silver Oak Leaf Cluster and one Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster | Air Medal w/ two Silver Oak Leaf Clusters and two Bronze Oak Leaf Clusters | Air Medal w/ one Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster | |

| American Defense Service Medal | American Campaign Medal | Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal w/ one 3⁄16" silver star | |

| World War II Victory Medal | Philippine Liberation Medal w/ one 3⁄16" bronze star | Philippine Independence Medal | |

| Army Presidential Unit Citation w/ one bronze oak leaf cluster | Philippine Presidential Unit Citation |

Medal of Honor citation

- Rank and organization: Major, U.S. Army Air Corps

- Place and date: Over Borneo and Leyte, October 10 to November 15, 1944

- Entered service at: Poplar, Wisconsin

- Birth: Poplar, Wisconsin

- G.O. No.: 90, December 8, 1944

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action above and beyond the call of duty in the Southwest Pacific area from October 10, to November 15, 1944. Though assigned to duty as gunnery instructor and neither required nor expected to perform combat duty, Maj. Bong voluntarily and at his own urgent request engaged in repeated combat missions, including unusually hazardous sorties over Balikpapan, Borneo, and in the Leyte area of the Philippines. His aggressiveness and daring resulted in his shooting down 8 enemy airplanes during this period.[15]

Commemoration

- Richard Bong State Recreation Area on the site of what was Bong Air Force Base in Kenosha County, Wisconsin

- Richard I. Bong Memorial Bridge along US Route 2 in the Twin Ports of Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin

- Richard I. Bong Airport in Superior, Wisconsin

- Bong Barracks of the Aviation Challenge program

- Richard I. Bong Bridge in Townsville, Australia

- Major Richard Ira Bong Squadron of the Arnold Air Society at the University of Wisconsin

- Richard Bong Theatre in Misawa, Japan and the 613th Air and Space Operations Center, Thirteenth Air Force, Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii.

- Bong avenues on the former site of the decommissioned Richards-Gebaur Air Force Base, on Lackland AFB in San Antonio, Texas, on Luke AFB in Glendale, Arizona, on Elmendorf AFB in Anchorage, Alaska, Fairchild AFB in Spokane WA and on Kadena AFB in Okinawa, Japan. Bong Blvd on Barksdale AFB in Bossier City, Louisiana.

- Bong Terrace, Mount Holly Township, New Jersey (Mount View neighborhood, built 1956–1957).

- National Aviation Hall of Fame (1986)

- Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame (1987).[16]

- Richard I. Bong Veterans Historical Center in Superior, Wisconsin. Housed in a structure intended to resemble an aircraft hangar, it contains a museum, a film screening room, and a P-38 Lightning restored to resemble Bong's plane.

- Richard Bong Veterans Historical Center

- Richard Bong Veterans Historical Center

Richard Bong Veterans Historical Center

Richard Bong Veterans Historical Center

See also

- List of Medal of Honor recipients for World War II

- Thomas McGuire, American combat pilot with the second-most enemy planes shot down, World War II

Notes

- ↑ Dear Mom, So We Have a War (1991)

- ↑ Kenney, George C. (1949). General Kenney Reports: A Personal History of the Pacific War. New York City: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. pp. 3–6.

- ↑ Yenne, 2009, p. 68.

- ↑ Military Ties-Hall of Valor, Richard Bong, Silver Star citation

- 1 2 3 "Factsheets : Maj Richard Ira Bong". af.mil. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ↑ Dick Bong America's Ace of Aces by Gen. George C. Kenney.

- ↑ HistoryNet

- ↑ HistoryNet

- ↑ Elaine Woo. "Marjorie Drucker, 79; Wife of World War II Ace Richard Bong". Los Angeles Times, October 10, 2003.

- ↑ Yeager, Chuck and Janos, Leo. Yeager: An Autobiography. Pages 227-228 (paperback). New York: Bantam Books, 1986. ISBN 0-553-25674-2.

- ↑ The New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times, among other periodicals, all carried prominent front page stories about Bong's death on August 7, 1945, despite the prevalence of the news on the first atomic bombing. "Jet plane explosion kills Major Bong, Top U.S. Ace," New York Times (August 7, 1945), p. 1; "Major Bong, top air ace, killed in crash of Army P-80 jet-fighter," Washington Post (August 6, 1945), p.1; "Jet plane explosion kills Maj. Bong; Ace's 'Shooting Star' blows up in test flight over north Hollywood", Los Angeles Times (August 6, 1945), p.1.

- ↑ Dear Mom, So We Have a War (1991)

- ↑ "Richard Bong". Claim to Fame: Medal of Honor recipients. Find a Grave. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- 1 2 "Aerial Victory Credits". Air Force Historical Research Agency. pp. (search on Name "begins with" "Bong", exclude those of BONGARTZ THEODORE R). Retrieved 2012-06-06.

- ↑ "Richard Bong, Medal of Honor recipient". World War II (A–F). United States Army Center of Military History. June 8, 2009. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Richard Ira Bong". Retrieved 10 December 2013.

References

- Bong, Carl (1993). Dear Mom: So We Have a War. Burgess Publishing. ISBN 0-8087-8413-7.

- "Bong, Richard". Medal of Honor recipients: World War II (A–F). United States Army Center of Military History. June 8, 2009. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- Kenney, George C. (2003) [1960]. Dick Bong: America's Ace of Aces. Superior, Wisconsin: Richard I. Bong WWII Heritage Center. ISBN 0-9722373-0-5.

- Yenne, Bill (2009). Aces High: The Heroic Saga of the Two Top-Scoring American Aces of World War II. Penguin Group. ISBN 0-425-21954-2.

External links

- "Richard I. Bong Veterans Historical Center".

- "Richard "Dick" Bong, American Ace of aces at acesofww2.com".

- "Richard Bong Historical Center".

- "AcePilots.com: USAF Bong".

- "Richard Ira Bong: American World War II Ace of Aces". Article by Jon Guttman

- "248th Hiko Sentai: A Japanese "Hard Luck" Fighter unit {Copyrighted-for reference only".}

- "USAF History. People: Major Richard Bong".

- Dejanovich, John (December 2012). "Wingman to the Aces, LT Floyd Fulkerson, Ultimate Wingman". Flight Journal.

- Richard Bong at Find a Grave